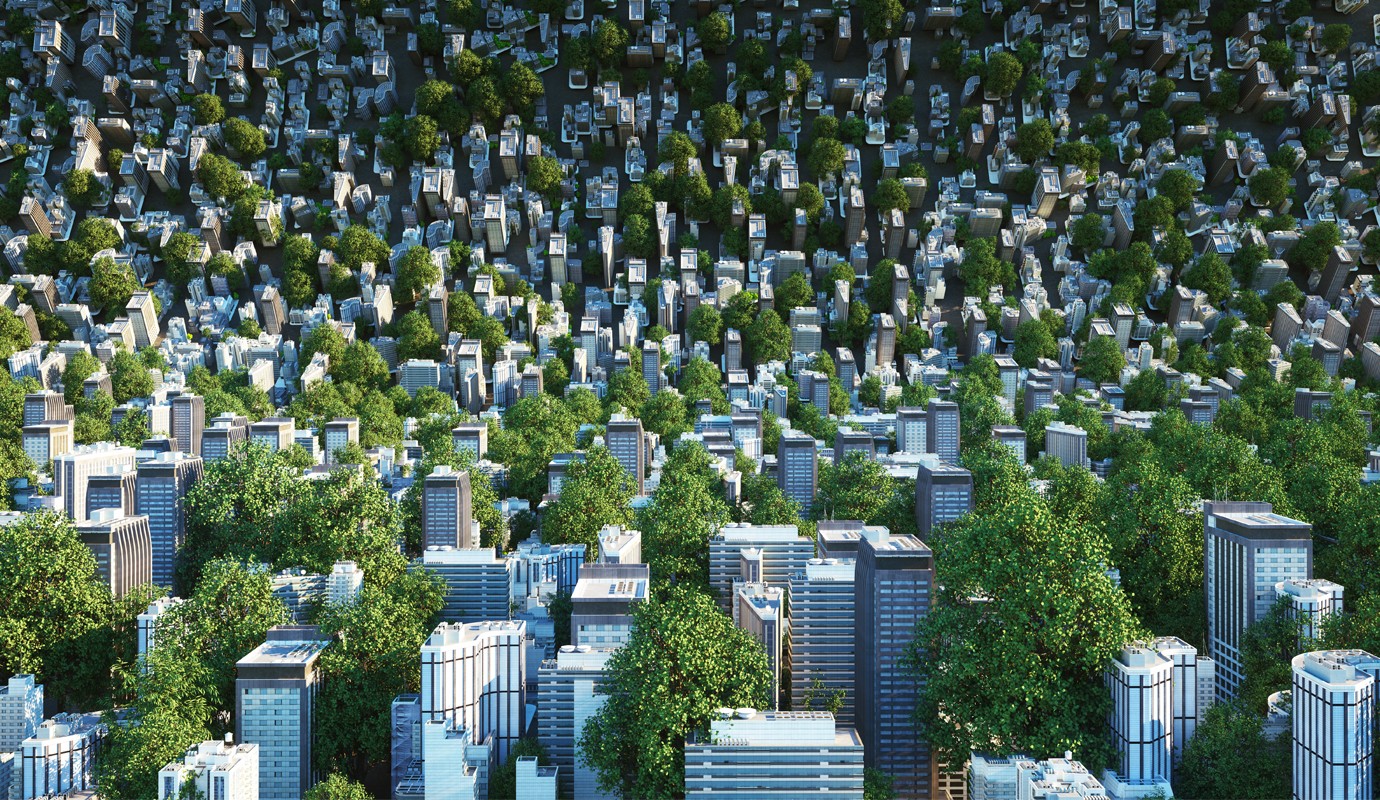

Building the Sustainable City

How governments and private business can foster environmentally sensitive urban planning.

In July 2006, London Mayor Ken Livingstone did something that few other public officials have had the foresight to do. Hoping to transform the city from one of Europe’s most polluted capitals to an environmentally conscious metropolitan area, Livingstone announced that the London Development Agency would develop a zero-carbon residential community on a three-acre site in the Thames Gateway. The facility would incorporate renewable energy technologies, energy-efficient architecture — for example, a building orientation that maximized solar gain, and enhanced insulation materials — as well as integrated waste management, on-site growing of food, and green transport systems. Construction is expected to begin this year.

European nations are leading the world in so-called sustainable urban planning, but Livingston’s radical project is among the most far-reaching efforts to date. The idea grew out of a simple fact of which few people are aware: Buildings account for about 40 percent of the world’s total energy consumption and 65 percent of electricity usage in the U.S. As noted by former Vice President Al Gore, improving energy efficiency in buildings represents “low-hanging fruit.”

For a number of reasons, however, the building sector has been slow to pick this fruit. Constructing a building is typically a complex, multiyear effort involving multiple organizations and individuals, including government authorities, landowners, developers, architects, engineers, and financial institutions in the early planning phase. And once a project is under way, construction companies join the effort, often managing an armada of suppliers and contractors. What virtually all of these interested parties have in common is a focus on short-term costs and profits. Consequently, in most planning and feasibility calculations, minimizing up-front expenses is paramount — yet these outlays will account for as little as 10 percent of the total cost of a building over its useful life, which is 50 to 100 years in developed nations. It is the operating expenses that constitute as much as 85 percent of life-cycle costs, with space heating and cooling, lighting, water heating, equipment, and appliances typically accounting for more than 60 percent of those outlays.

One true “sustainable urban community” is currently under development in the United Arab Emirates (UAE); made up of two towers projected to combine residential, commercial, and retail space, it is expected to break ground this year. Its sustainability “premium” on up-front construction costs — that is, the extra expense of including environmentally friendly features — is about 15 percent. However, the project’s Swiss and British planners and engineers estimate that the project will reap as much as 80 percent energy savings over its lifetime, thanks to an optimized mix of facilities; improved insulation approaches; radiant cooling, which uses chilled water as opposed to forced air for air conditioning; and photovoltaic as well as other solar power systems. Overall, this combination of approaches translates into an attractive internal rate of return of about 20 percent.

Nowhere is the opportunity for sustainable urban planning and development more pronounced than in the developing world, especially in Asia. The Asia-Pacific region is home to 55 percent of the world’s population and has more than doubled its consumption of ecological resources since 1961, according to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and environmental watchdog Global Footprint Network. The World Bank estimates that by 2015, more than half of China’s urban residential and commercial building stock will have been erected during the previous 15 years. And in India, the largest developer plans to build 750 million square feet of retail, commercial, and office space in the near future, three times the amount it constructed in the previous six decades. But in the midst of this building boom, Asia has the chance to improve its heretofore less-than-exemplary environmental record. In their report titled Asia-Pacific 2005: The Ecological Footprint and Natural Wealth, the WWF and Global Footprint asserted that these building trends present an opportunity for the region to “shape the world’s path towards sustainable development in the coming decades.”

Some officials in Asia have begun to recognize that they must act differently than the West has or they will pay a huge price in environmental catastrophes and rising energy costs. In a December 2006 speech, Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh wondered rhetorically whether growth is “sustainable if development in the developing world merely mirrors the experience of the developed” world. The Chinese Communist Party–controlled newspaper China Daily proclaimed in February 2008 a “farewell to the GDP growth cult,” noting that “GDP must be based on environmental sustainability.”

A number of initiatives in China focused on promoting sustainable development have come to the fore in recent years. For example, Huangbaiyu, a poor village in Liaoning province, was chosen in 2003 as the site of China’s first model “eco-village,” and the massive eco-town of Dongtan near Shanghai is set to open in 2010 at the start of the Shanghai World Expo. Other towns have taken more mundane approaches. Rizhao, a city of 3 million in Shandong province, is focusing on maximizing the use of solar power. Today, 99 percent of households in Rizhao’s city center and 30 percent in the suburbs are reported to have solar panels for lighting and water heating. Although some environmental experts have been skeptical of these statistics as well as of China’s overall commitment to sustainability, these projects appear to be a step in the right direction.

For all its long-term benefits, sustainable urban planning will not become commonplace without significant support from many of the more powerful elements involved in major building projects. For example, governments can set tougher environmental standards for construction efforts, provide incentives for building in a sustainable way, and educate the development community about sustainable techniques. Among the financial benefits that governments can offer to subsidize environmentally friendly projects are tax breaks, fast-track permits, or lower prices on land that is under their control. (See “The Critical Enabler,” by Gary M. Rahl, s+b, Summer 2008.)

More farsighted governments should be encouraged to take these steps because of the potential positive spillover from sustainable, healthy buildings: lower health-care costs; increased employment in advanced engineering, construction, and facility management; additional investment from global companies; and improved public relations for cities, regions, or countries. Such bragging rights, as well as bottom-line economic gains, were a prime motivator behind Abu Dhabi’s Masdar City, another UAE project, touted by its developers as the “world’s first zero-carbon, zero-waste, car-free” urban community. Initiated by a government-owned development company, which invested US$4 billion in Masdar City out of a total yearly budget of $22 billion, the 1,500-acre site is likely to begin construction this year. It will include a special economic zone housing companies involved in alternative energies and sustainability research, and it is forecasted to attract more than 1,500 businesses and generate billions in macroeconomic benefits for Abu Dhabi.

Governments in Europe have also taken tentative steps to corral some of the benefits of sustainable development. Switzerland and Denmark have adopted stringent construction regulations with strict, specific guidelines for energy consumption, depending on the size and type of building. The European Commission calculated that if Denmark’s rules were applied throughout the E.U., projected energy consumption could be reduced by up to two-thirds. Germany, for its part, has offered tax incentives to homeowners who build new homes or retrofit existing homes according to energy-friendly guidelines.

Investors, developers, and property owners must also wake up to the economic opportunities that sustainable buildings present. This means looking at costs from the perspective of the building’s total life cycle, including planning, construction, operations, and even demolition. Moreover, innovative developers should look at the revenue side. A variety of studies have quantified the impact of clean air and a pleasant environment and found that they lead to higher productivity and lower tenant turnover in office buildings, longer visits by shoppers and increased purchases in retail environments, and improved sleep and higher levels of concentration in residential properties.

Consumers, too, must become aware of the impact of their choices and behaviors. This was made plain in a somewhat unorthodox way recently in South Korea, where citizens typically keep the thermostat high during chilly winters and the air conditioning working overtime during hot and humid summer months. According to an economist who has studied energy usage in buildings, the nation could reduce its energy consumption by 10 percent if the population simply kept room temperature at 72 degrees during cold weather. To help improve citizens’ bad habits, South Korea’s largest broadcasting company recently visited the homes of the foreign community living in Seoul to film a documentary meant to educate Koreans on how and why foreigners use significantly less energy.![]()

Author profiles:

Nick Beglinger is managing partner of Maxmakers, a Swiss company active in sustainable real estate and infrastructure development, including Abu Dhabi’s Masdar City.

Tariq Hussain is Maxmakers’ northeast Asia representative, based in Seoul, Korea.