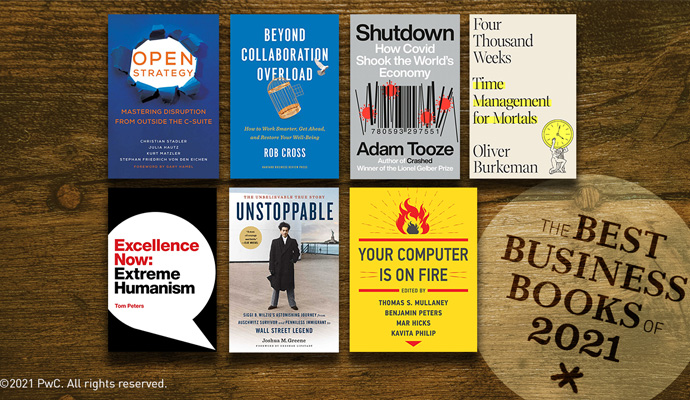

Best Business Books 2021: Making attention pay

In Four Thousand Weeks, journalist Oliver Burkeman distills the central dilemma for today’s consumers: how to efficiently allocate time.

Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals

by Oliver Burkeman (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021)

For a certain kind of person, just reading the title of Oliver Burkeman’s book Four Thousand Weeks is anxiety-producing. Four thousand weeks, after all, is the time most of us get on earth—if we’re lucky. And, as Burkeman acknowledges, for most of us, it feels like a cruelly small amount of time, given how much we want to do, and see, and be. “We’ve been granted the mental capacities to make almost infinitely ambitious plans, yet practically no time at all to put them into action,” he writes.

The natural reaction to this is to vow not to waste a moment, to strive to do everything faster and more efficiently. But in this book, Burkeman, a British journalist, makes the opposite point. This is a book about abandoning the delusion that time is something you can manage successfully. Trying to live as efficiently as possible, Burkeman argues, is both futile and self-defeating. There is always more to do, always another small task to complete, and, paradoxically, the better we get at completing tasks, the faster new ones arise. Obsessing over time management therefore means spending your time trying, and inevitably failing, to create more time for yourself. It means living always in the future—that future when all the to-do items have been checked off—and as a result, never living in the present. Instead of helping us clear the decks for the stuff that’s really important, trying to be on top of everything really means that most of our time is spent on the things that matter less.

Although Four Thousand Weeks offers plenty of lessons about work, it’s also the year’s best book about consumer behavior. That’s not just because it has a lot to say about how the attention economy warps our experience, but because it’s a book about consumption in the deepest sense, a book about how we spend our time. As Burkeman puts it, in one of the book’s most haunting sentences, “When you pay attention to something you don’t especially value, it’s not an exaggeration to say that you’re paying with your life.”

The challenge, of course, is that we live in a culture, and an economy, that seems practically designed to get us to pay attention to things we don’t especially value. At work, technologies designed to make us more efficient and productive by enabling faster and easier communication often, in practice, make it hard to do what writer Cal Newport calls “deep work.” There’s always something new demanding our attention, forcing us to toggle between tasks (or, even worse, forcing us to try doing different tasks at the same time).

The same is true, oddly, about our “leisure” time, which for many of us no longer feels leisurely. Time is a constant presence online, and the logic of efficiency—of doing as much as possible in the time we have—is pervasive. When you read a book on a Kindle, it tells you not just how many pages you have left, but also how much more time it will take to read them. When you finish a show or movie on Netflix, you aren’t even allowed to watch the credits in peace—whatever Netflix thinks you should watch next gets immediately queued up. In this world, any individual piece of content is just grist for the mill, and the goal is to make the mill run as fast as possible (think of all the people who listen to podcasts at 1.5 times normal speed), because there’s always something else for you to see or hear.

So why do so many of us behave as if we are content-consuming hamsters on a wheel? As Burkeman says, some of it is a function of the way social media and entertainment companies use persuasive design to keep us hooked. But the deeper problem, he argues, is that we are in thrall to the idea of endless possibility, and to the illusion that it’s possible to never miss out. We act as if we have all the time in the world, so that it’s possible to see and do everything we want. And as a result, we’re constantly in fear of missing out.

The reality, of course, is that there isn’t time enough to watch everything, read everything, do everything. The task, as it were, is to recognize this and make your peace with it. “Once you truly understand that you’re guaranteed to miss out on almost every experience the world has to offer,” Burkeman writes, “the fact that there are so many you still haven’t experienced stops feeling like a problem.” Letting go of all the things you haven’t done, but imagine you could do, lets you focus more intensely on the things you are doing. As Buddhist scholar Geshe Shawopa told his students hundreds of years ago, “Do not rule over imaginary kingdoms of endlessly proliferating possibilities.”

Burkeman doesn’t pretend this is easy. He himself was once obsessed with maximizing efficiency, and he clearly still feels the pull of that impulse. Giving up on the fantasy that you can be all things means giving up on possibility, accepting limits. (As Burkeman puts it, the real challenge is “how to decide most wisely what not to do.”) And, if you do it right, giving up in this way means figuring out what you really care about, and how you really want to spend your time, and then following through. That can be nerve-wracking, which is one reason that even when we’re doing things we enjoy, we still flee so readily onto Twitter and Facebook and YouTube. Yes, those sites are doing their best to distract us. But, Burkeman writes smartly, “We give in to distraction willingly. Something in us wants to be distracted…to not spend our lives on what we thought we cared about the most.”

Once you truly understand that you’re guaranteed to miss out on almost every experience the world has to offer, the fact that there are so many you still haven’t experienced stops feeling like a problem.

So how do you avoid this? Burkeman offers practical tips: spend the first hour of every day on the thing that matters most to you, work on no more than three things at once, and be careful to avoid not the things you don’t care about, but rather the things that you sort of care about, since they are the easiest things to waste time on. But the book’s real message is something deeper: recognize your limits, both in terms of how much you can do and how long it will take to do it, and cultivate what Burkeman calls an active, muscular patience. In German, the word Eigenzeit describes, in Burkeman’s words, “the time inherent to a process itself.” Whatever you choose to do, Burkeman suggests, you should surrender to its Eigenzeit rather than try to hurry things up. (Of course, your boss may not respond all that well if you explain that a project is late because of what its Eigenzeit requires.)

Four Thousand Weeks has not remade my relationship to time or even to Twitter. But it has helped me recognize those occasions when worrying about doing the next thing is erasing my attention on what I’m actually doing, and it’s made me think more deeply about giving the things I care about the time they deserve, and the value of letting the world come to me. Reading Burkeman’s book, I was reminded of a quote from Kafka: “You do not need to leave your room. Remain sitting at your table and listen. Do not even listen, simply wait. Do not even wait, be quite still and solitary. The world will freely offer itself to you and be unmasked, it has no choice, it will roll in ecstasy at your feet.”

Honorable mentions:

Wanting: The Power of Mimetic Desire in Everyday Life

by Luke Burgis (St. Martin’s Press, 2021)

Luke Burgis’s Wanting is a compelling and insightful look at the way our desires are shaped by the desires of others. We don’t just imitate other people, Burgis argues; we come to want what they want. Burgis explains that this impulse toward mimicry shapes what we buy, where we go, even what partners we end up with, and tries to show us ways to break free of the gravitational pull exerted by those around us and how to carve out one’s own way of wanting.

Arriving Today: From Factory to Front Door—Why Everything Has Changed about How and What We Buy

by Christopher Mims (Harper Business, 2021)

Christopher Mims’s Arriving Today is, in large part, a book about supply chains and logistics. But it’s also very much a book about consumers, and how their insatiable demand for things to be fast and cheap has reshaped transportation systems, factories, and workers’ lives. This is an excellent look at what it takes to satisfy our need for instant convenience, and it’s the kind of book that should make consumers think about what it means to consume the way they do.