Lessons in simplicity strategy

Using a six-point “hexagon action” model to deal with a complex world helps leaders focus and prioritize their work.

A version of this article appeared in the Autumn 2021 issue of strategy+business.

Wouldn’t it be nice if we could just take a simplicity vaccine that would immunize us from the chaos in our world? COVID-19 has made the everyday disruptions of the modern age infinitely more complicated for businesses, affecting everything from supply chains to office culture. But we do not have to accept complexity as the dominant force in our lives. In fact, as the world begins to emerge from the pandemic, there is evidence that the recovery will come about faster if leaders set aside complexity and pursue an organizational reset based on simplicity itself.

Developing a culture and practice of simplicity takes deft leadership skills, but the rewards are high. Apple’s remarkably powerful brand was built on Steve Jobs’s ferocious dedication to simplicity in design. The exponential growth of the market for calmness and wellness apps also illustrates how we hanker for simplicity. Global search firm Heidrick & Struggles found that 67 percent of “high-accelerating organizations” had embraced simplicity in their strategy, operating model, and culture. Sean Stannard-Stockton, president of Ensemble Capital, a California-based investment firm, argues that simplicity is a very clear antidote to “the detrimental effects that complexity has on investment performance.”

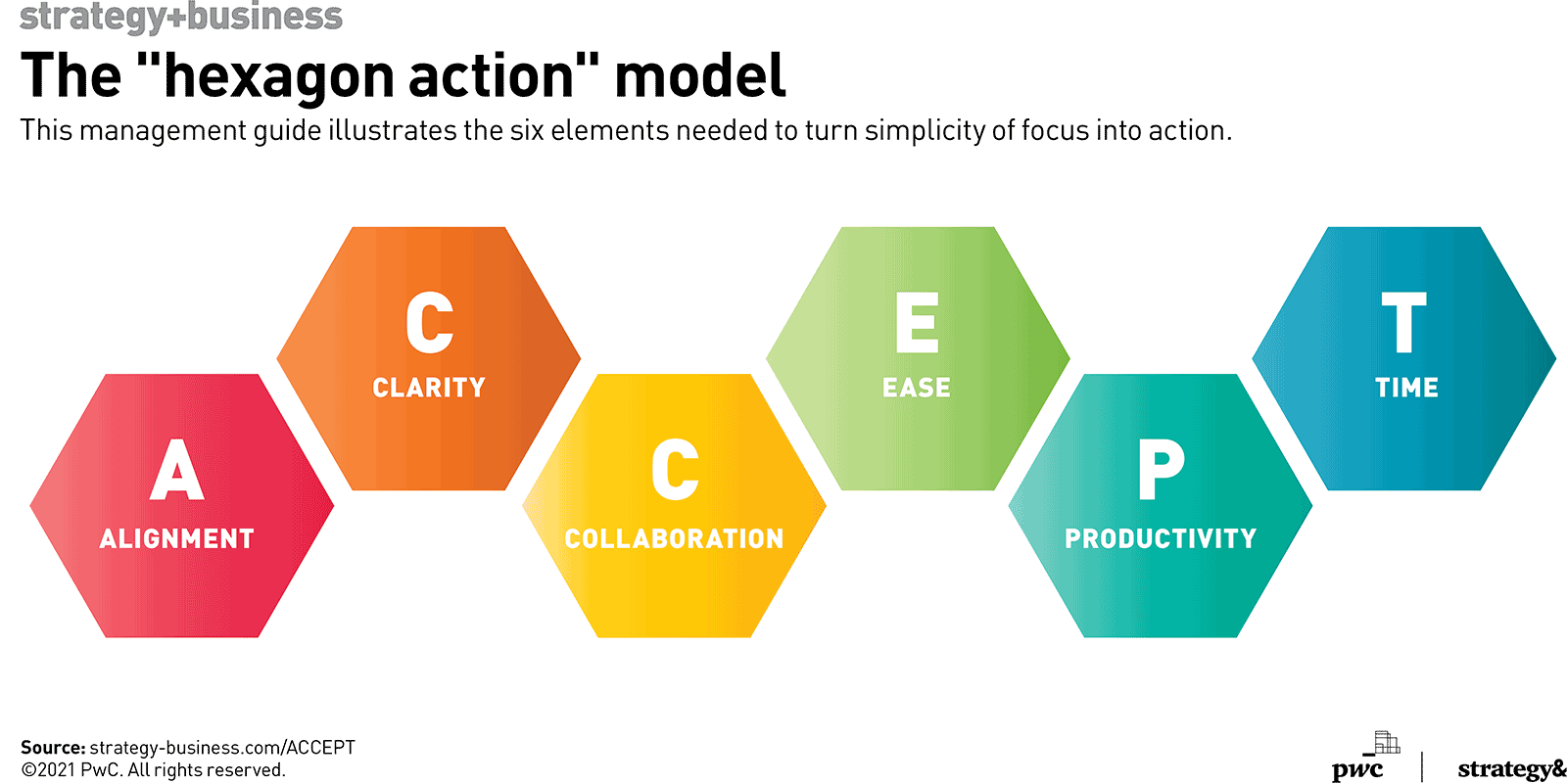

My actionable strategy helps leaders prioritize, focus, and cut through complexity. Called the Simplicity Principle, it updates the famous KISS principle (“keep it simple, stupid”) of design thinking, which the U.S. Navy first described in 1960. It also echoes Jack Welch of GE and his famous “speed, simplicity, and self-confidence” strategy. How to achieve such simplicity? What follows is a guide to the six-point management model I call “hexagon action.” It embodies the Simplicity Principle — where I suggested using the number six as an organizing tool — and helps to hone an approach that focuses on what matters and getting things done.

Developing a culture and practice of simplicity takes deft leadership skills, but the rewards are high.

Strategies based on hexagon action models are flexible and can be applied to all sorts of settings, including personal productivity and creative brainstorming. In his classic book, Good Strategy, Bad Strategy, Richard Rumelt argues for “reducing the complexity and ambiguity in the situation, by exploiting the leverage inherent in concentrating efforts on a pivotal or decisive aspect of the situation.” So, simply adopting a “stick to six” rule would be progress.

However, the six-part hexagon action model illustrates how to turn simplicity of focus into action. It’s based on an acronym, ACCEPT: alignment, clarity, collaboration, ease, productivity, and time.

First, a short explanation of the power of six and the hexagon.

Perfect six

Six, as I have written before, is a useful organizing number, and is the smallest in a range of numbers described in mathematics as “perfect.” A number is perfect if it is a positive integer that is equal to the sum of its divisors. Six, of course, is the sum of one, two, and three. Six is also workable, definable, measurable, and memorable. If you adopt a small-is-better mentality (I love the two-pizza rule, which says if your working group can’t be fed by two pizzas, it’s probably too large), six gives you a guideline that can be established and maintained fairly quickly.

The hexagon, nature’s diamond, lends itself beautifully to organizational management because of the way it embodies interconnection, resilience, and economy. Like the equilateral triangle and the square, the hexagon tessellates, which is to say it can connect to the same shape without gaps (unlike, say, circles, an all-too-popular PowerPoint intersecting image). This is crucial, because so much of what people do intersects and connects. The hexagon is a powerful visual aid and connects us to network theory in which “edges” play a crucial role. By using a model that has a shape with sides and boundaries, we can better contain and manage our thinking and our strategic action.

Then there is versatility: The “perfect” nature of the number six means that the smaller integers of one, two, and three all fold neatly into it. I often work with teams on “half a hexagon” to identify the three things they will do now as they “triage” their priorities. Action is an all-important word, because it focuses on deeds. A lot of leaders can get mired in talking rather than doing. We don’t have time to lose as we rebuild and renew our businesses and institutions post-pandemic. And for this reason, the concept of simplicity strategy is anchored in action.

ACCEPT is actionable strategy in practice. Imagine you are turning a hexagonal axle inside the wheel of your organization, starting with one side, marked A, and rotating through the letters of ACCEPT:

Alignment. Alignment involves balance and symmetry. This fits perfectly with the geometry behind hexagon action. Basically, being aligned means making sure you and your team are on the same page. If you aren’t, the way you are looking at an issue is asymmetrical (and thus not aligned). The leader who can grasp these asymmetries will have greater visibility into and control over what has to shift to bring things back into balance.

William Eccleshare, worldwide CEO of Clear Channel Outdoor Holdings, was candid with me: “The pandemic has thrown up that organizations grow more complex without you realizing it. I was surprised by how many organizational layers we had created in a multimarket, multifunctional organization with all of the corporate governance that comes with being a public company. All of those things together just made the organization much, much harder to control.” He notes that it is difficult to be aligned when there is a lot of organizational clutter. The antidote? “What we’ve done is try very consciously to reduce the number of organizational levels that there are, to make it simpler to get something to happen,” he said.

Clarity. Clarity is a critical component of the Simplicity Principle. In physical and mental health, “brain fog” is a symptom of illness and stress. But all too often, organizations suffer from a similar lack of clarity. When Howard Schultz returned to Starbucks in 2008 after an eight-year absence to nurse it back to health, he could not have been clearer about his agenda in his memo to the staff. “The company must shift its focus away from bureaucracy and back to customers,” he declared. And the goal was “reigniting the emotional attachment with customers.” Jake Pugh, a British capital markets expert who focuses on strategy, told me that he has long held the view that “simplicity achieves better outcomes. A culture of openness and clarity is key to driving engagement and positive outcomes.” In the summer of 2019, when the U.S. Business Roundtable set out to convey its new ethics-driven agenda, it described it as one “that allows each person to succeed through hard work and creativity and to lead a life of meaning and dignity.” That is a good example of putting clarity front and center in a strategy.

Clarity concerns not just the macro but the micro. Early in my career, a client fixed me with a beady eye and asked a question in six succinct words: “Julia, what does success look like?” Corny, but true. And I have not forgotten how clarifying that moment was; it informs my own work on a daily basis. Clarity begins at home. If leaders ask themselves how clear they feel about something, and how clear their purpose is, they will have a greater chance of success.

Collaboration. Collaboration and community are closely entwined, especially at work. Philosopher and psychologist William James famously said, “The community stagnates without the impulse of the individual. The impulse dies away without the sympathy of the community.” In an influential article for Harvard Business Review on collaboration, Lynda Gratton and Tamara J. Erickson, both professors at the London Business School, identified the winning formula in companies that “demonstrated high levels of collaborative behavior despite their complexity,” and found that companies that combined training in collaborative skills with support for informal community-building improved team performance.

Collaboration is a key component of what I call social health, namely the behaviors people employ to communicate and collaborate both in person and using technology. The new hybrid working model will require managers to have high degrees of emotional literacy so they can motivate people and look after their “social selves” whether they work from home, in an office, or in between, in what I’ve called the “nowhere office.” Job van der Voort, the former head of product at GitLab who went on to found Remote.com, an HR services company that simplifies global hiring, says he and his team have six separate daily check-in opportunities to ensure they stay connected and can just bring up whatever is happening. This need for structure was echoed by several CEOs I spoke to recently, one of whom said, “We always have a 9:30 a.m. team meeting. If people have something else [going] on, fine, but this routine anchors everybody, and we know there is a space to just say what’s on your mind.”

Ease. The “hard–easy effect” is a well-known cognitive bias that means we think we do hard things better than we do easy things. In other words, “easy” is valued less than “hard,” often incorrectly. This means we can overlook the power of what is easy because we think hard is preferable. When it comes to results — and hexagon action wants results, after all — we need to look at the psychology of ease, and specifically at heuristics, those mental shortcuts we make to help solve complex problems when faced with incomplete information. We need to be clear we are not avoiding easy things for the wrong reasons.

There is no doubt that the Simplicity Principle seeks effective shortcuts that can cut through complexity. In his bestseller, Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones, James Clear makes a persuasive case that when we rely on self-control, which is by definition hard, we engage in what is “a short-term strategy.” For Clear, the solution is to make activities you want to limit difficult and make the habits you want to build and maintain easy. Technology companies understand this. It has been more than a decade since Amazon introduced its “collaborative filtering” algorithm, also known as “Recommends” and “Also bought.” It was described at the time by Fortune as “based on a number of simple elements.” It’s estimated that 35 percent of Amazon customer sales were generated by recommendations.

You may think that most of leadership is being tough, making the hard decisions. But what if you need to pivot and think the opposite? What you should in fact do is focus on making the things you have to do easy and do more of them.

Productivity. The P word stalks the C-suite. And I don’t mean purpose, the new kid on the corporate block. No, I’m talking about productivity. Well before COVID-19, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development was estimating slow growth in that crucial ratio of output to input, which has been stubbornly weak since the 2008–09 financial crisis. The world is united in having “a productivity puzzle.”

Productivity should be aligned — back to the first side of this hexagon action model — with clarity and collaboration, which in turn leads to better well-being. Corporate well-being programs have mushroomed in recent years, and the data points impressively toward improved performance and productivity when a strong program is in place. When workplace well-being is poor, organizations experience higher degrees of stress-related absenteeism. Stress was, according to the World Health Organization pre-pandemic, “the health epidemic of the 21st century.”

That isn’t to say that productivity monitoring is the answer, even in the guise of employee well-being. Microsoft was rightly criticized for its clumsy Productivity Score software, which some critics say is thinly disguised surveillance. But regardless of how you measure it, or even define it — for some it is creativity and for others it is sales — the simple fact is that if productivity is not strong, something is badly wrong in the organization. Better communication and connection (and clarity and collaboration) create higher trust and higher productivity. So, pay attention to your P word.

Time. How do you measure time? There are two kinds of time: the kind you spend in your own way, and the time that other people control. How people manage time is changing. Increasingly, the generation Z workforce wants to be fully flexible and fully mobile. This impulse led to the rise in coworking spaces before the pandemic. Yet the way people spent time when at work before COVID-19 was still largely structured around presenteeism and a set number of hours worked in a sequence.

Now that more and more of us work from home, the problem of when to stop working is far harder to gauge. Still, this border should be made explicit. In March, David Solomon, chief executive officer of Goldman Sachs, was forced to issue a statement ring-fencing Saturdays as a day to not work, after younger workers staged something of a revolt over excessive hours.

As distributed networks of workers grow, or migrate from city center to suburbs, managing time “zones,” either literally or as a demarcation of actions, will become necessary. Last year, Gratton, who is also head of the World Economic Forum’s New Agenda for Work, Wages and Job Creation, suggested that “work might need to be scheduled to fit around family as opposed to the other way round.”

Time can also be seen through a simplicity lens. Given that research now shows the time cost of distraction is around 30 percent when workers are zigzagging between being online and offline (23 minutes and 15 seconds during an hour of activity, to be precise), creating simple strategies that respect how hard it is to manage time would make sense. Technology entrepreneur Tom Adeyoola described steps he has taken to organize his life when he appeared on my podcast: “I try to make things as simple as possible. So I spend the first part of the day trying to think about the important things to do. Only three things, tops for me. And then everything else that you put on a to-do list [is] just things that are never urgent and important.” That’s a half hexagon in practice.

Accepting complexity

Despite my belief in simplicity and in the ACCEPT model, it would be foolish to completely overlook the reality that we are always going to be stuck with some aspects of complexity: As economic commentator Martin Wolf told me, “Complexity is inevitable, because due to our ability to create staggeringly complex institutions, we also face insuperable problems of control.” But increasingly, we need to cut through and develop new customs, cultures, and practices. And because that is difficult in a complex world, as Eccleshare of Clear Channel Outdoor Holdings says, “the simplicity approach calls for greater leadership, not less leadership.” I think we all need to accept that.

Author profile:

- Julia Hobsbawm is the author of the award-winning The Simplicity Principle: Six Steps Towards Clarity in a Complex World and the founder of The Simplicity Principle consultancy. Her new book, The Nowhere Office, will be published later this year.