Daniel Defoe’s hard-earned lessons on business and life

The author of Robinson Crusoe, who dealt with ups and downs as an entrepreneur, also penned one of history’s most useful business manuals.

Talk about writing for money! In 1692, a businessman named Daniel Defoe was forced into bankruptcy by a debt of £17,000 — a sum approaching US$4 million in today’s money. Defoe had succumbed to bad bets and overexpansion, hubris and high living. He’d deceived family, friends, and business connections, too. But once his debts were discharged, he worked hard to repay them nonetheless, whittling the total to just £5,000 by 1705.

New business ventures enabled him to bounce back. But so did the power of his pen, unleashed by the disaster of going broke. A writer of astonishing productivity, Defoe is mainly known to modern audiences for such novels as Robinson Crusoe and Moll Flanders. But he was also arguably history’s greatest business writer, and his output includes probably the first English business manual, The Complete English Tradesman, from which, even today, you can learn a great deal about commerce, credit, and capitalism. It first appeared in 1726 — when Adam Smith was roughly 3 years old — and was reprinted in the colonies by no less a figure than Benjamin Franklin, himself a comparably entrepreneurial polymath and man of many faces. For a while it was a popular handbook for merchants on both sides of the Atlantic.

“Trade and commerce were to be among Defoe’s favorite topics as a writer,” the Defoe scholar John Richetti has observed, adding that “he thought of the merchant as the new hero of the new age and its commercial ethos, and he frequently grew eloquent on the subject.”

He was also insightful about the social and ethical dimensions of business, thereby foreshadowing what Smith would later write on the same subject. We’ll get to all this momentarily, I promise. But first, we ought to know a little something about Defoe’s life and times, which offer their own lessons for today’s business leaders.

Rough times

If you like to think you’re managing in a challenging and fractious environment, Defoe’s experience will help you to stop feeling sorry for yourself. He was born Daniel Foe (he embroidered his last name in adulthood) in the heart of London in 1660, the very year the Stuart monarchy was momentously restored. But in the next few years, bubonic plague spread death and desolation through London, and the Great Fire laid waste to much of the city. As a young man, Defoe risked his life in an ill-fated revolt against the new Catholic king, James II. He was imprisoned more than once, sometimes for debts, other times for politics.

Defoe’s family also suffered the persecutions visited on religious dissenters at the time. The Foes had become Nonconformists, or Protestants who (despite great risks) refused to adhere to the practices and theology of the established Church of England. That made young Daniel part of an oppressed (if irrepressible) minority that was excluded from universities and key roles public life. Despite their small numbers and disfavored status, these dissenters still achieved outsized success, particularly in business and finance, where they could more freely channel their energies at a time when Britain was evolving from a traditional agrarian society into a capitalist colossus.

Defoe was no dour Puritan. A slick dresser and bon vivant, he liked keeping a coach and horses, and a bad case of status anxiety left him with a chip on his shoulder. He was also reckless, mercurial, egomaniacal, and, as a businessman, prone to desperate measures, some of which were unethical. At one point, he borrowed money to buy civets in order to trade in their musk. But he used the money to pay other creditors, obtaining the malodorous creatures on credit instead. Then he sold the civets to his mother-in-law, who only afterward discovered that he didn’t actually own them.

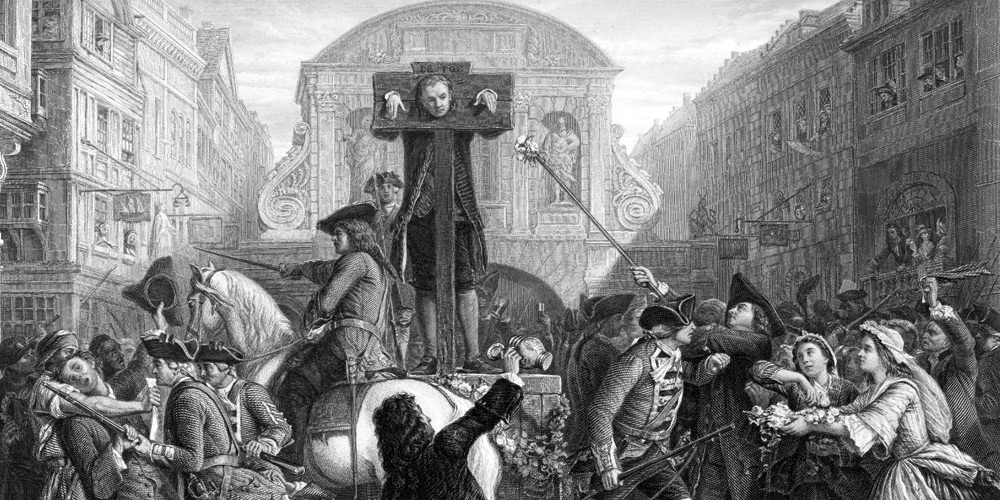

Why take business advice from such a person? Because, unlike the armies of b-school professors and management gurus who’ve never met a payroll, Defoe’s business guide is based on hard-won experience: making and losing fortunes, cultivating patrons, overcoming bitter enemies, and twice surviving bankruptcy. During his long life, he was confidant to a king and victim of the pillory. He even lived through the South Sea Bubble.

Building grit

Doggedly resilient, terrifyingly energetic, unfailingly audacious, and devilishly persuasive, Defoe was an early prototype of the modern entrepreneur and promoter who, warts and all, we depend upon more than we may know. Aside from civets, his ventures included manufacturing, import–export, shipping, insurance, finance, and publishing. At one point, he invested in an enterprise to recover sunken treasure using a diving bell. Later in life he became a spy.

Defoe was an early prototype of the modern entrepreneur and promoter who, warts and all, we depend upon more than we may know.

The Complete English Tradesman originally ran to nearly a thousand pages in two volumes and is marked by some of Defoe’s characteristic excesses, including compulsive verbosity and a tendency to beat a subject to death long after he’s made his point. Maybe this is why a one-volume edition, published in Edinburgh in 1839, appears to be the text most commonly used today.

This shorter version still overflows with insights — on business communications, dealing with staff, the hazards of partnerships and rumors, making promises (for example, to repay) that both sides know might not be kept, and spending too much on overhead. A striking element here is that the tradesman in Defoe’s vision — and of course this would apply to the tradeswoman as well — is not seen in isolation; on the contrary, he’s part of a social network, as humans must always be if they are to thrive, of obligation involving family, servants, lenders, customers, and others.

Not surprisingly given his personal experience, some of the author’s most interesting advice has to do with managing failure. Defoe’s 1692 bankruptcy, in particular, left him with a lifelong burden of guilt and a sense of stigma. This no doubt played a role in his advice to tradesmen that, if they are to go broke, they should do so when the handwriting is clearly on the wall, rather than continuing to drag their creditors ever deeper into trouble.

Pulling the plug is never easy. Defoe himself lived by his own observation that, “A Tradesman is never out of Hope to rise till he is nail’d up in his Coffin.” But irrational hope in a failing business can doom not just creditors (to bigger losses), but the businessperson working so hard to succeed. When the end comes, as it almost surely will when it’s so close on the horizon, the postponed catastrophe is even larger, and a fresh start is correspondingly more difficult. Thus, Defoe recommends brutal honesty with creditors, the reward for which is likely to be earlier access to credit for the debtor (“the life and blood of his trade”) after the fall. “I speak it to every declining tradesman, if you love yourself, your family, or your reputation, and would ever hope to look the world in the face again, break in time.”

Defoe is especially conscious of the connection between business and family. “A wife and children,” he writes, “are as much a tradesman’s real creditors as those who trusted him with their goods.” He sees it as crucial for those in business to keep their spouses informed of what’s going on at the office, and is quite explicit about “the great and indispensable obligation there is upon a tradesman always to acquaint his wife with the truth of his circumstances, and not to let her run on in ignorance, till she falls with him down the precipice of an unavoidable ruin.”

In the event of a businessperson’s death, a well-informed spouse can carry on the trade, or at least collect what is owed. Sharing the truth when things aren’t going well at work can also help the family avoid one of the chief pitfalls Defoe sees in the path of those who would otherwise succeed in business: extravagance, which he describes as “a secret enemy, that feeds upon the vitals.”

Distraction is perhaps just as dangerous, as Defoe, an obsessive multitasker, knew well. Someone who goes into business and doesn’t really focus on it “murders his credit, he murders his stock, and he starves, which is as bad as murdering, his family. Trade must not be entered into as a thing of light concern; it is called business very properly, for it is a business for life.”