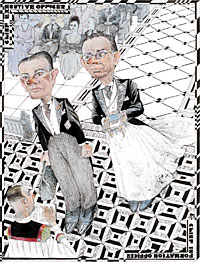

CEO vs. CIO: Can This Marriage Be Saved?

Improving organization and communication will help chief executives and chief technologists form a more perfect — and profitable — union.

(originally published by Booz & Company)

|

|

Illustration by Jack Unruh |

The audience laughed. In fact, their laughter was more spontaneous and contagious than it was at any other time during that daylong seminar. The irony, of course, was that the attendees were completely unaware that the CEO was dead serious. For this assembly of CIOs, the idea that a CEO would call one of their number “essential” was, well, laughable.

The unfunny truth is that CEOs and CIOs too often act as though they are partners in an enormously uncomfortable marriage. That’s not to say that there hasn’t been some improvement, even significant improvement, in this relationship in recent years. In fact, at an increasing number of companies, there has been a growing emphasis on integrating IT operations into the most vital aspects of the business and on ensuring that technology plays a key role in future success. In a Booz Allen Hamilton survey of CEOs conducted in August 2000, 70 percent of respondents said that leveraging e-business is the most important or a very important issue on their agenda. And 89 percent of CIOs questioned at the same time indicated that there had been a clear, bona fide expansion of their responsibilities in the previous 24 months.

Still, in our experience, this progress is occurring generally only in large and established companies with enlightened management. In most organizations, there still is a long way to go before the CEO and CIO find common ground. It’s not that chief executives are Luddites who are ignorant about the potential impact of technology on their companies. That charge could perhaps have been leveled a decade ago. But most CEOs are now well aware that improved productivity (even if it can’t be easily measured) from advances in technology was the underpinning of the nation’s longest economic expansion. And many have accepted the conclusion that the Internet is forcing a reinvention of the way their companies do business with consumers, suppliers, and partners, and is fundamentally altering how their employees communicate with one another.

The problem is that most CEOs are interested in technology only to the extent that it adds value to the organization. To them, CIOs are experts only in technology and service delivery. Some other executive — the CFO, a business unit head, a sales manager, for example — has to point the CEO in the right direction before computers, networks, BlackBerrys, PDAs, mobile databases, and any other technology become integrated with the strategic direction of the corporation.

CIOs, of course, are not blameless in allowing this perception — this breakdown in the marriage, so to speak — to take hold. Although they often say that they aspire to more strategic involvement, few technology chiefs are skilled enough to align their agenda with their company’s agenda, and, just as importantly, with the business landscape in which their company must operate. CIOs should be defining technological initiatives in terms the business understands — speeding products to market, enabling growth, and reading costs and risks. If CIOs adopted that kind of approach, top management might be inspired to take them more seriously as partners in developing the company’s strategic direction.

Rather than embrace this opportunity, however, most CIOs tend to view themselves as corporate victims, shut out of the executive suite and seat of power through no fault of their own. This perception, which inevitably feeds a vicious circle, has a clear impact on CIOs’ careers: CIO longevity in the job averages less than two years, and the reason almost half of all CIOs wind up fired is that they fail to establish good working relationships with their CEOs and the rest of the management team. No wonder many in the industry believe that “CIO” stands for “career is over.”

The losers in this corporate family standoff are frequently the companies themselves. When CEOs and CIOs treat each other as if they’re from different planets, companies are potentially deprived of an essential component of any business plan: the ability to link the latest technology smartly and innovatively to the company’s strategic priorities. Imagine the missed opportunities from this troubled relationship — the unrealized benefits in customer relations, supply chain, inventory, and marketing; the internal knowledge networks allowing corporate sites around the world to share information in real time with one another that are never built; the mobile databases or distributed data channels that no one dares even consider; the potential efficiencies and improved productivity that never materialize.

Tally that up and it’s clear how costly the gap between CEOs and CIOs is to many companies. In the pages that follow, we explore what’s gone wrong between chief executives and chief technologists and why these relationships are constantly foundering. Our goal is to define a plan for making the marriage work.

We begin by identifying the three critical areas that need the most attention:

- Organization: This involves how the CEO structures the management of a company — especially where the CIO sits in the decision-making flow. Organization also comprises how skillfully the CIO uses his or her executive position to align the technology agenda with corporate strategic mandates and to produce a return-on-investment program that matches the business conditions in which the company is operating.

- Communication: Going beyond how CEOs and CIOs simply communicate with each other, this encompasses the way CEOs convey the importance of technology and of the chief technologist to the management team. This is crucial because the CIO relationship with management peers is frequently even more strained than the relationship is with the CEO. Communication includes how persuasively and intelligently CIOs express the technology agenda to the press, industry executives, investors, and employees in light of the company’s business, sales, manufacturing, and marketing plans.

- Process: This entails where the chief technologist fits in the procedural makeup of the company and specifically deals with how much management control the CIO has over technology projects once they’re slated for business units. Does the CEO trust the CIO only enough to let him or her be the head of the team that plugs in the machines? Does the CEO grant the CIO and the business unit chief co-responsibility for the nontechnological corporate decisions that have to be made when implementing a new technology?

Technology and the Org Chart

To leverage technology to the greatest degree and to integrate it with the company’s strategic business goals, it’s essential that the chief executive include the CIO among his or her closest advisors and decision makers. Different companies have different ways of formalizing the structure, but whatever the configuration is, the CIO must be an equal to the business unit heads. The reason for this goes well beyond just giving the CIO more visibility in the organization so he or she can proactively implement new technologies, although that is a possible by-product of this arrangement. More important, it’s a way to ensure that senior management — the top dozen or more executives at the company — set the IT priorities for the organization together. If they all “own” the technology agenda, then the resistance to carrying it out — for instance, concern among business units that technology is a cost item that will hurt their P&L results long before it helps — will be mitigated. After all, if the CEO and every other top manager agree that a $150 million effort to provide wireless connectivity for the sales force is a desirable project that will keep the company’s plants at the cutting edge of efficiency, the head of the sales unit could hardly be penalized for working with the CIO to carry out the plan.

Of course, this structure requires greater strategic acumen from the CIO than many have yet demonstrated. Often, in fact, CIOs have to demonstrate their skills as strategists even before they are elevated to peer roles with other executives. (See “The Four Roles of the CIO,” at the end of this article.) In short, the CIO has to help the CEO justify remaking the organization to include the chief technologist among the top decision makers. To do this and eventually participate in the company’s agenda setting, the CIO has to learn to frame his or her technology solutions in a business construct and to balance them against other business priorities. For instance, that wireless sales network may have to be weighed against the option of hiring additional sales staff. The CIO can’t just argue for the technology in a vacuum; the CIO has to champion it by comparing it to the other choices that the company has and by using his or her unique expertise to describe the transformational opportunities specific to the company that the technology offers. For example, to make a case for recommending mobile access to data for existing salespeople, a CIO may have to work closely with the sales chief to jointly produce a concrete proposal with clearly delineated reasons — everything from hoped-for strategic outcomes, to improvements in productivity, to cost versus return — that the proposal will bring more revenue to the company in the next year or so than will adding 10 more people to actually sell the products.

That kind of cooperation between CIOs and business unit heads is rare. In fact, the wide gap between CIOs, CFOs, and other business managers may have a larger negative impact on corporate performance than the chasm between CIOs and CEOs. Understanding the importance of strategic technology in today’s business environment and how essential it is to continue to expand technological resources (even though this can be costly) is difficult for many nontechnical managers who are focused on the bottom line. It’s part of CIOs’ burden to tear down the wall between themselves and their peers in the executive suite — and it’s to their benefit to do so. As long as that wall exists, we believe it is virtually impossible to improve decision making involving technology implementation and to convince CEOs to view CIOs as trusted managers.

It’s also important for the CEO to view the parts of the CIO’s organization devoted to providing infrastructure services (e.g., company networking, systems management) differently than other “business-facing” departments. The former are not strategic activities — frankly, they’re more akin to utilities than core businesses — and it’s unfair to judge them on the basis of return on investment. They’re requirements and costs of doing business. By failing to separate IT service from IT strategy — and comprehend that the CIO is ultimately responsible for both — CEOs often grow frustrated with their chief technologists, confused as to whether they should be asked to provide merely utility or something much more critical than that. The answer is, CIOs need to manage both, and for the relationship between CEOs and CIOs to work, that unique dynamic has to be understood.

In some companies, typically outside the United States, the problem of distinguishing between the nuts-and-bolts aspects and the strategic aspects of the CIO’s job is mitigated by an organizational structure in which the corporation is run by a management board or an executive committee. Under this collective management approach, generally the person on the board responsible for IT is a nontechnologist — a senior executive — who has already proven his or her skills in the business and with whom the CEO is usually comfortable sharing tactical decisions. This nontechnical “CIO,” in turn, usually oversees an IT executive, for example, a senior executive VP or general manager whose job it is to lead the day-to-day IT organization according to the policies of the management board; in other words, to direct all the traditional procurement, software management, and infrastructure activities.

Barclays PLC, the giant international banking group, illustrates this organizational setup well and is evidence of how effectively this structure can facilitate an enduring and positive relationship between the CEO and the CIO. Not only is Barclays the U.K.’s leading Internet bank — for both consumers and businesses — but it is also completely overhauling its core technology infrastructure to offer new retail services to customers nimbly, without long, drawn-out launches. This endeavor has been greatly enhanced by the relationship CIO David Weymouth enjoys with CEO Matthew Barrett on the company’s Group Executive Committee. Mr. Weymouth is a 24-year veteran of Barclays, a nontechnologist who took over the bank’s vast technology operations (with a budget well over $2 billion) in 2000. Mr. Weymouth’s initial reaction to the importance of having a CIO on the Group Executive Committee is that it stretches the CIO’s role considerably, because it “forces me to create the strategy as well as deliver on it. I’m in the beginning of strategy generation, where there’s a competition for resources, human and monetary. And like any other member of the Executive Committee, I have to compete for them.”

This has given Mr. Weymouth a keen appreciation for the politics and priorities of business planning that are required for IT projects — and a deeper understanding that successful technology strategies, like all other critical ventures at a company, must be championed by a manager who has to build consensus and convince peers to agree on the plan. Being part of the executive board meetings forces a CIO to fit the technology to the corporate strategy, Mr. Weymouth says, and it imposes a discipline on the CIO to produce strict return-on-investment estimates for every project he or she recommends. “I can’t get away with anything but the most rigorous calculations,” Mr. Weymouth says. “Sometimes it has to do with value creation and what that’s worth compared to the cost of the project, and sometimes it’s simply careful benchmarks that can be tracked very closely to see if we’re meeting them. But either way, before I suggest anything, I know I have to justify it, and ultimately that ensures that the technology we implement will help the company to the maximum degree.”

All of this has impressed CEO Mr. Barrett, who has staked much of Barclays’s future on using technology to deliver significant benefits internally and externally (to customers). “We don’t get lots of detailed memos that say do this and do that,” Mr. Weymouth says. “He tells us that providing the best service to the market is important, and that technology is important to providing the best service. That’s the strategic framework, and my job is to work with the Group Executive Committee to devise IT answers that fit it.”

Bridging the Communication Gap

In contrast, the merger of the Union Pacific Corporation and the Southern Pacific Rail Corporation was a marriage made in hell. In 1996, Union Pacific, the U.S.’s No. 1 railroad, paid $4 billion to purchase Southern Pacific, in hopes of gaining a stronger foothold in the Southwest. But within a few months of the deal’s completion, hundreds of abandoned freight trains were strewn throughout Texas as Union Pacific lost track of entire cargoes of plastics, chemicals, coal, and grain. Some deliveries ran as much as 40 days late. And Union Pacific customers — the nation’s biggest shippers — suffered more than $2 billion in lost sales in the two years following the acquisition. Union Pacific itself fell nearly $700 million in the red in 1998. The main culprit: Union Pacific’s ambition had outstripped its common sense. Southern Pacific, a troubled railway for years, had been monitoring its trains with an outsourced computer network that was so ancient it was being held together with the logistics equivalent of baling wire. Unaware of this, Union Pacific tried to impose its more sophisticated, organized, and up-to-date tracking system on Southern Pacific’s creaky enterprise, and the result was one of the worst debacles in railroad history.

But as bad as the merger was — and although Union Pacific is profitable again, it only now is getting Southern Pacific under control — the deal and its aftermath highlighted a far worse dysfunctional relationship in the Union Pacific family: Chief Information Officer L. Merill Bryan, Jr. was not among Chief Executive Officer Richard Davidson’s inner circle of advisors. In fact, Mr. Davidson hadn’t told Mr. Bryan about the purchase of Southern Pacific until after it was completed, even though numerous other top executives — even some sales and marketing managers — had sat in on some of the negotiations and had been asked by Mr. Davidson for their opinions.

In hindsight, Mr. Bryan says that had he been included in merger discussions, he would have warned top management that Southern Pacific’s computer systems couldn’t handle the complicated logistical strains of a modern railroad. And although he might not have recommended against the deal, he could have tallied up the millions of dollars it would cost to integrate Southern Pacific within the Union Pacific system, which could have put Union Pacific in a strong position to cut the price of the acquisition.

The repercussions of the large gap between CEO and CIO at Union Pacific were a very public embarrassment for the railroad company. But in perhaps less visible and quieter ways, this same relationship-on-the-rocks scenario, placing the CEO and CIO at opposite ends of the executive corridor, is being played out — with similarly costly results — at a large number of companies around the world.

The message is clear: Communication drives organization. Creating a management and decision-making structure at a company that includes a significant role for the CIO is only the beginning; after that, a CEO must strongly communicate support for not only the CIO, but also the technology that the CIO represents. Otherwise, turf battles between business units and technology champions will inevitably break out.

There are many ways for a CEO to publicly express backing for the CIO and mend the relationship. One is to put the CIO on the calendar for regularly scheduled meetings — once a week or so, or at least as frequently as the CEO meets alone with the head of sales, marketing, manufacturing, and the like. This is not just a formality. It’s a chance for the CEO to question the CIO about technological initiatives that are suited to the company’s current plans and those not even announced, and it’s an opportunity for the CEO to share private corporate information, such as the existence of ongoing merger discussions, and elicit the CIO’s opinion. On the flip side, it gives the CIO a platform to show that he or she is ready for managerial strategizing.

Another way for a CEO to communicate support for the CIO is for the CEO to equate the organization’s success with the implementation of the most advanced and highly leverageable technology; in other words, to make it clear that this dedication is one way the company can outrank its competitors. Simply investing in technology, however, is not enough. The CEO’s commitment must be grounded in targeting specific value opportunities created by technology. That, for instance, is what occurred at Kinko’s Inc., which has transformed itself from a campus-oriented copying center into a web of “branch offices” for small businesses fully outfitted with the latest networking, communications, and document-production technology. Kinko’s has also launched Kinkos.com, which lets people design brochures, business cards, and other materials online and place an order to pick them up at a nearby retail store. CEO Gary Kusin, facing rivals that range from stores like Mail Boxes Etc. to major manufacturers like Xerox, Canon, and Kodak, has said at numerous investor and analyst meetings that the current technology initiatives are just the beginning for Kinko’s — faster equipment, wireless access, and more sophisticated networking with customers are all in the works — and that the company’s future success depends on doing much more.

Defining a company as technologically savvy can pay big dividends for a CEO. It attracts investors and analysts because it paints an image of a company discarding old business models to create a modern organization taking the kinds of intelligent risks needed to succeed and add value to the company in today’s complex business environment. And that’s where the CIO’s communication responsibilities come in. If the chief executive is a technology champion — someone willing to bridge the gap that separates the executive suite from the technologists’ bullpen at many companies — then the CIO must become the CEO’s very visible partner in this effort. CIOs may not have had the chance to develop internal managerial skills, but they must acquire them in order to present business rationales and carefully calculated return-on-investment scenarios. Similarly, CIOs must develop the ability to articulate to the press, industry leaders, Wall Street, and nontechnical employees the company’s core technology vision and how what flows from this vision will impact the organization’s financial and operating performance.

At most companies, CIOs are not public faces and usually aren’t complaining about it. They may eagerly speak at a technical conference arguing an engineering point relating to a wireless network they’re installing, but we can’t recall the last time a CIO appeared on a quarterly earnings analyst call to describe how the just-completed customer relations telecommunications system will impact revenue and profits in the coming year. That just exacerbates the suspicion among CEOs that their chief technologists are not business leadership material because such a large part of the job of any corporate executive is publicly advocating the company’s vision and strategic priorities. Kinko’s Chief Technology Officer Allen Dickason calls it being a translator and readily admits that it is a critical part of his job and, equally important, an essential skill if the relationship between him and the CEO is to be productive and respectful. “I have to be able to explain in plain English the details of the technology strategy that the CEO is alluding to,” he says. “If I can’t translate the excitement and the innovation in plain words — not techno-babble — that anyone can understand, whether they’re a business unit head or an investor at a road show, then I’m failing in the communication aspect of my job.”

Process Management

Process is the most difficult part of the CEO–CIO relationship to navigate. Even with the best intentions, it can take a long time to truly integrate the CIO into the core activities of the company’s business units — in other words, to make certain that the CIO is involved in day-to-day supervision of the numerous processes driving the company that are linked to technology, whether customer relations management, factory floor automation, sales and marketing database development, or something else.

Most CEOs are too “hands-off” to recognize whether this level of coordination between the CIO and the business units is occurring. The relationship can be crucial to the company’s success, however. It’s certainly necessary to ensure that technology expenditures — often among the costliest budget items — are not wasted and, in fact, are leveraged throughout the organization. But most CIOs are too unskilled in company politics and too uncomfortable with nontechnical performance benchmarks to deftly insert themselves into strategic corporate processes, those that go beyond simple networking. And that’s where the CEO–CIO relationship breaks down. The CEO neglects how technology is being implemented at the company — no matter how supportive of technology that CEO is. And the CIO often is unable to be an aggressive tactical manager.

One of the few examples of a company that has successfully bridged this gap is a Midwestern industrial giant, whose CEO has demanded that when the CIO heads an initiative, he is responsible not only for developing and installing the system itself, but also for managing (or comanaging with the business unit chief) the value that the system brings to the company. For instance, the CIO tackled this dual role when redesigning the company’s customer-service system through the first few stages of its launch by having customer-service staffers report directly to him as well as to the head of the business unit. This way, the CIO had supervisory-level access to the employees’ frontline input about the technology, and he could continually assess without interference or bureaucratic struggles which areas of customer service improved or failed under the new system. Based on these results, the CIO was able to fine-tune the technology to meet certain company performance and value benchmarks that he measured himself, not just technical specifications.

This type of hands-on process management by a CIO of a business unit and this degree of cooperation between a CIO and a business unit head, although tremendously valuable, is extremely rare, primarily because most CEOs don’t endorse that level of CIO involvement. Without it, though, we’ve found that a disturbing cycle has set in at many companies, in which business unit heads are avoiding the CIO and hiring outside help to design non-mission-critical applications. Kept out of the stream of ideas at the process level of the company, the CIO is unable to efficiently leverage the new technology across the company or, importantly, pollinate technological concepts throughout the corporation. This, in turn, makes the CIO seem even less knowledgeable and capable of strategic management.

Of course, the CIO may exacerbate the situation. Frequently, when the IT group is asked to do something quickly, such as turn around a marketing campaign in days to respond to a competitor’s actions, it reacts by saying the project could take months. Frustrated by this response and knowing they don’t have that long to wait, the business units go elsewhere to get the campaign off the ground. Eventually, this disconnection between business units and the CIO comes back to haunt the company in the extra costs to pay outsiders to do what IT staffers should be doing, the maintenance and support headaches, and the difficulty in keeping track of equipment purchases and technology inventory.

To stop this spiral, CEOs must be vigilant, making sure, for instance, when a business unit head proposes an initiative involving technology, even in an offhand conversation, that the CIO is included in the discussion. One way to accomplish this is to discourage making key process-oriented decisions outside the scope of executive committee meetings.

As with everything else related to healing the fractured relationship between CEOs and CIOs, however, both sides must participate. Once he or she has the CEO’s imprimatur, the CIO has to foster the process relationship with business units by providing demand-management strategies that help scope, model, and prioritize technology expenditures. This way the business unit head has a good idea at the beginning of the budget year what the expected technology costs will be and can decide, with the CIO, how to spread the limited money available. If something unexpected occurs, such as a sales effort that wasn’t anticipated, the CIO, closely involved as he or she would be with the day-to-day activities of the business unit, can move funds from another department to this project — and, importantly, gear up IT staff to tackle it in crisis mode — or pitch the executive committee for a larger budget.

Perhaps the CIO who has most successfully made process management the centerpiece of his job description is John McKinley, chief technology officer of Merrill Lynch & Company. He showed his stripes soon after he joined Merrill in 1999 by guaranteeing that, in six months, the company would have an online presence that would rival those of Schwab and E-Trade, two of the many Web brokerages that were making Merrill look like a dinosaur with its old-fashioned telephone and in-person approach to trading stocks. Mr. McKinley assembled a team of 30 people, many of them borrowed from the business units that would be involved with the Web site, and had constant discussions with business unit heads about how the site should look and operate. The team met the deadline, in large part, says Mr. McKinley, because the consensus management approach ensured that many parts of Merrill’s organization felt they had a hand in building the site and, thus, wanted it to succeed. But only a few people — Mr. McKinley and some of the key business unit heads who would be involved with the online initiative — made the final decisions about how to proceed.

Mr. McKinley, with unwavering backing from CEO David Komansky, has continued to ably find the seam in the process at Merrill and deftly maneuver his way into close working relationships with every business unit, even when he anticipates (and finds) resistance. Earlier this year, Mr. McKinley boldly pitched Merrill business unit heads on a new commitment to technology, even as the company was about to initiate a round of firings. His strategy is for the business units to use their limited technology budgets to build customer retention programs; he argues that it’s far less expensive to generate more business from existing clients than to acquire new ones. Some of Mr. McKinley’s ideas include enhanced customer relationship management databases, more client self-service programs both on the Web and off, and new products like a Net-based portfolio analysis service to help customers assess their investments.

“Projects fail — no business unit would consent to them — unless they have a financial and company value benchmark to meet,” Mr. McKinley said a few years ago in an interview. “If it’s not a sustainable model financially, it’s a waste of resources. In the early days of e-business, people said, ‘You can’t measure Web profitability and return on investment.’ Well, everything can be measured. Ultimately, if you can’t measure something, you can’t improve it.”

Spoken like a CIO to whom corporate process is not an alien concept.

A Brighter Future

In the last five years, CEOs and CIOs have demonstrated that they can work together in any number of industries in a variety of circumstances. The CEO whose public commitment to his CIO drew a round of laughter at that seminar ran a company in which every strategic initiative had a technology component. In the face of difficult conditions in the CEO’s industry, the transformation of his company through technology is one of the few positive operational achievements keeping manufacturing and sales operations from collapsing.

Similarly, the CIO who steps up to the challenges of building and maintaining a strong relationship with the rest of the management team will soon realize the competitive advantage of information technology. Tactical attempts to bridge the distance in this relationship by improving organization, communication, and process are just the beginning. But they’re essential first steps toward the increased revenue, efficiencies, cost cutting, and innovation that can potentially result from a healthy partnership.

And who knows? Maybe then, no one will laugh. ![]()

|

The Four Roles of the CIO |

|

The office of the CIO has one desk and at least four different chairs. At different times and in different situations, the CIO is called upon to be a strategist, a business advisor, an IT executive, and an enterprise architect. These four roles require substantially different skills, and each one is critical to ensuring the success of IT in supporting and enabling the business. The Strategist is on the senior executive team and helps define and structure the business. The strategist understands the opportunities presented by technology as well as its costs and risks. The successful strategist will translate IT’s potential into meaningful financial and business capabilities and evaluate the future payoff of uncertain technologies. The Business Advisor is a peer to the business unit heads and helps translate IT’s value to and impact on day-to-day business processes and practices. The advisor’s primary objective is the delivery and capture of value, which, in turn, requires tight linkages to each business unit’s strategy and processes. The successful advisor will translate IT investments into tangible, realizable, measurable benefits. At the same time, the advisor will translate, communicate, and deliver value in ways that can be understood by the businesses. Key focus areas are process and organization redesign, business case development, application delivery, rollout, and training. Because IT organizations can be large and complex, with responsibility for managing and ensuring 24/7 operations across a broad range of infrastructure, including networks, desktops, mainframes, telecommunications, and application development, the IT Executive is accountable for skills, training, assets, investments, reliability, and the security of all systems. This executive manages the cost and performance of a broad array of external service providers, contractors, and outsourcers. Such fiscal demands stretch the traditional IT skill set, and the job resembles program management for a major product platform. The Architect creates an enterprise architecture that optimizes investment, enables growth, and ensures linkage to the extended enterprise. And he or she does so without sacrificing security or reliability. The architect’s key challenges are maintaining scalability to flex with the business, introducing technologies, and driving system migration planning and sunsetting of legacy systems. — T.P. |

Reprint No. 02308

| Authors

John O. Boochever, boochever_john@bah.com John O. Boochever is a vice president in Booz Allen Hamilton’s London office. He works with financial institutions, helping senior management translate market strategies into technology agendas, build new capabilities based on business demands and opportunities, and enhance the performance of existing operations. Thomas Park, park_thomas@bah.com Thomas Park is a principal with Booz Allen Hamilton in Chicago. He specializes in helping clients leverage IT to drive business strategies, improve operational effectiveness, and deliver value. He works primarily in the automotive, aerospace, and defense industries. James C. Weinberg, weinberg_jim@bah.com James C. Weinberg is a senior vice president in Booz Allen Hamilton’s Chicago office. He partners with clients on developing strategic transformation programs and building IT-enabled capabilities in the automotive, aerospace, and industrial sectors. |