Skoda Leaps to Market

A Communist car monopoly turned Volkswagen subsidiary is now becoming an entrepreneurial global enterprise.

(originally published by Booz & Company)

|

|

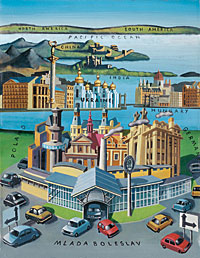

Illustration by John Howard |

Skoda certainly faces its challenges — including a fraud and bribery scandal that erupted just as this article went to press, and that threatens to engulf the Czech car company and its corporate parent, Volkswagen AG, in months of investigations and controversy. But however that scandal evolves, there is also a fundamental story to tell about the company’s strategic position — as the most successful and globally oriented manufacturer to emerge in any category from a former iron curtain country. With sales in 85 countries (not including the U.S. or Canada, where its cars are not sold), Skoda is being closely watched as an emerging worldwide brand in the rapidly maturing, ruthlessly consolidating, and already oversupplied automobile industry. In short, Skoda has found a way to capitalize on its past strengths while transcending many of its historical weaknesses — a skill that would benefit any brand. The next few years will tell whether Skoda is an anomaly or a demonstration that former Communist-controlled enterprises can thrive in a capitalist economy. If Skoda can do it, others can too.

One would have to search widely to find a viable company today with a political history as turbulent as that of Skoda. It began operations in 1895, making bicycles and motorcycles; in 1905, its first production car, the stately Voiturette, was pushed out of its original workshop. In its early years, the company made luxury cars. Then it survived the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the creation and rise of Czechoslovakia, the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Nazi Germany, the 1948 Communist takeover, the 1968 Soviet invasion, the 1989 revolution that overthrew Communism and introduced the free market, the 1993 split of Czechoslovakia into two independent countries (the Czech Republic and Slovakia), and the 2004 entry of the Czech Republic into the European Union. Skoda also survived being swallowed in 1991 by an entirely different type of autocratic regime: Volkswagen. That company, which is partly owned by the provincial government of Lower Saxony, is known for its committee-based management style, its insular culture, its innovative designs, its intimate labor relations, and its long-standing identity as the largest European automaker.

Volkswagen, of course, has its own turbulent past: founded by 19th-century master engineer Ferdinand Porsche, adopted as the Third Reich’s car company by Adolf Hitler, and then, with the popular Volkswagen Beetle, revived as the populist carmaker of postwar democracies. Unlike Renault, the French carmaker, which made a bid at the same time, Volkswagen didn’t propose to buy Skoda and merge it with VW’s operations; instead, it acknowledged that Skoda had been a great carmaker before the Nazis and the Communists got hold of it, and that it could be a great carmaker again.

But Volkswagen executives make a point of not talking publicly about their thinking, so it isn’t clear whether they deliberately designed “leapfrogging,” the business strategy that made Skoda successful, or stumbled into it by accident.

Leapfrogging into Competitiveness

Skoda currently has three cultural identities. First, it is the industrial flagship of the Czech Republic and a vehicle of national pride — a role that its German owners are careful to cultivate. Five percent of the working Czech population is employed directly by Skoda or indirectly by its suppliers. Skodas account for 8 percent of Czech exports, departing the landlocked country on rail transports stacked three decks high. Skoda still has a 48 percent market share at home. The green winged-arrow Skoda logo predominates on Czech roads. Almost every Czech institution of emotional resonance, from the state ballet to the national ice hockey team, is sponsored in some way by Skoda. Moreover, it has become the core company in a growing Eastern European automotive cluster that produces more than 3 million passenger vehicles per year. Factor in car production in Poland, Hungary, Romania, Bosnia, and Ukraine, and the former Communist bloc begins to look like a European “motor city”: a cluster of manufacturers and suppliers on the scale of Detroit or Toyota City.

Skoda’s second identity — a transition it has now completed — is as a profitable division of Volkswagen. If Skoda’s heart is Czech, its head is German. Integrated within Volkswagen’s management structure, the company follows the established VW formula for success: performance-oriented management, cooperative labor relations, utilitarian marketing (the famous “Think Small” ads developed by Doyle Dane Bernbach in the 1960s set a pattern for highlighting value that continues to this day), and an emphasis on design. And although Volkswagen has struggled visibly in recent years to maintain earnings, Skoda’s results since the acquisition have exceeded the business’s wildest expectations. In 2004, the company’s pretax profits doubled to $209 million on sales of $6.65 billion. Since 1991, production has increased from 170,000 poor-quality cars to 451,000 award-winning cars. In Germany, Skoda has successfully competed against sales of Volkswagen’s own branded models. Within the parent company, that is seen as a small price to pay for building a brand capable of growing Volkswagen’s total sales while allowing the more established Volkswagen brand to migrate up-market in search of bigger margins.

The third identity, just now emerging, is as a global brand, leapfrogging past the more mainstream brands from countries with longer capitalist histories. Leapfrogging is the term increasingly used to describe the competitive play made by developing nations (and some companies within them) in wholesale implementation of the latest technologies and working practices. For an emerging economy, leapfrogging provides a more consequential platform for growth than mere outsourcing, because it paves the way not just for current growth, but also for future competitive advantage. Mobile phone penetration and computer-based government services, for example, are more prevalent in Eastern Europe than in the rest of the European Union, which is burdened by its legacy infrastructure.

“Our model should be Finland,” says Martin Jahn, the head of CzechInvest, the government’s agency for attracting foreign investment. He argues that the Czech Republic, with its industrial heritage and high-quality engineering schools, can become a center of motor vehicle and transportation innovation — in the same way that Finland, a relatively small European country, has advanced in the global economy by investing in education and telecommunications.

Skoda has done its own share of leapfrogging, building a supply and distribution network for its cars that is leaner and more intelligent than the supply chain networks of most carmakers in Western Europe. Using large plots of land left over from Communist-era dealerships, Skoda commissioned architects to design state-of-the-art buildings, at costs far below those of other dealerships Volkswagen was obliged to maintain. Skoda’s new factories were designed, from the start, to accommodate self-organizing work teams (known at Skoda as “fractals”), which made productivity goals and rewards easily attainable. Skoda also brought supplier staff directly onto its assembly line in Mladá Boleslav — a manufacturing innovation that allowed the auto manufacturer to cut its inventory costs to almost nothing, improve quality through closer integration with its suppliers, and earn rental income from the same suppliers (who would otherwise have had to build their own factories).

Leapfrogging in itself does not explain Skoda’s success. Cheap labor was also not the decisive factor (many labor markets are less costly than the Czech Republic these days). Other factors included Volkswagen’s precise school of management, the integration of Czech and German corporate cultures, and the positioning of Skoda as a smart, rather than cheap, buy. Probably the greatest factor of all was the deliberate appeal to pride — pride in craft, pride in design, and general pride in company — in a culture and country where that emotion had been in short supply for many years.

|

| Skoda factory, Mladá Boleslav. Photograph courtesy of Skoda |

Newborn near Paradise

An hour’s drive north of Prague, the new “motor city” of Mladá Boleslav differs from Detroit in its size (its population is about 43,000), its architecture (the churches and castle date back 800 years or more), and its formal foundation in the 10th century a.d. by Boleslav the Pious (“Not to be confused with Boleslav the Cruel,” notes a town official). Leaders of the early Protestant Czech Brethren movement, which made Mladá Boleslav its own Jerusalem, were in communication with Martin Luther in Wittenberg, with Desiderius Erasmus in Amsterdam, and with John Calvin in Geneva. The Communists added a lot of concrete, some Marxist statues, and a few loudspeakers tied to streetlamps, but did not fundamentally alter the town’s sense of self.

The Skoda car plant stretches a mile across, with a railway running through it. On one side, beyond the towering red and white chimney stacks, is a splendid baroque chapel by Giovanni Alliprandi. On the other, stacked up like gray vertebrae, are the Orwellian apartment blocks built by the Communists to house factory workers. (Since 1989, many families have moved to new houses at the edge of town.) In the distance is Cesky Raj, literally “Czech paradise,” an exquisite series of soft stone hills topped with fairy-tale castles and bounded with stands of oak. This is where Czechs dream of living when they retire, where German executives slip off to for a celebratory lunch, and where newborn Skodas get their first spin.

Inside the car plant everything is orderly, clean, regular. Skeletal cars proceed like cogs through an expensive watch. Orange robot arms rotate to weld car roofs and sides. Farther along, teams of uniformed workers install parts by hand. It is difficult to see who is working for Skoda and who for a supplier renting out space on the assembly line. In terms of nationality, the plant is also mixed: Most of the blue-collar workers and many managers are Czech, but the senior executives tend to be German, imported from VW’s Wolfsburg headquarters.

“Germans and Czechs just fit together,” says Milan Maly of the Prague University of Economics, an expert on contemporary management structures in Eastern Europe. “German managers are very precise, very strict, but making decisions is suffering to them. Czech managers are bigger individualists, better innovators.” He singles out as significant an early German decision to bring order to the Skoda plant’s parking lot. “People were parking all over the place, but Czech managers thought it crazy to worry about such a detail when there were production issues to resolve. The Germans were proved right. First bring order, then comes change.”

Today, to a casual observer, the Skoda plant feels like a hybrid of the two cultures. The offices have the crisp efficiency typical of German layouts, whereas the canteen embodies a scruffy and unpretentious style that the Czechs seem to prefer. Three languages are spoken in the plant: a clipped English or German by the executives, and English or Czech by their subordinates and by the blue-collar employees, who tend to be young and to spend as much time text-messaging on mobile phones as they do talking.

Skoda prefers to keep observers at arm’s length. Managers are reserved around journalists, with on-the-record discussions restricted to the directors. “We have no interest in the American market, therefore we have no interest in talking to Americans,” says Jaroslav Cerny, the company spokesperson.

Out from Communism

The nadir of Skoda’s 100-year history was probably 1968, when the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia to put down the “Prague Spring” revolts. As punishment for opposing the invasion, Skoda’s best managers and engineers were sacked or put to work on the assembly line. The Politburo also scrapped two higher-quality car models (the S-720 and S-740), which had not yet finished development. Quality and morale dropped, and so did the last shreds of the carmaker’s reputation. When the Communists finally decided to invest in more competitive models (which they named Favorit and Forman) in the 1980s, they had to hire an Italian designer, bring back political undesirables, and introduce one of the only incentive programs in the Communist bloc.

Skodas exported to Western Europe during Communism received a scornful reception. The cars were perceived as smelly, noisy, and only vaguely responsive to their steering wheels and brakes. The brand became a joke, a shorthand for all the inadequacies and failings of the Communist bloc. (A typical example: “What do you call a Skoda at the top of a hill? A miracle.”) Then, in the chaotic months following the 1989 Velvet Revolution, which saw the dissident playwright Václav Havel become president, the new government made privatizing Skoda one of its first priorities. The Czech government whittled a list of 24 potential investors down to just two: Volkswagen and Renault. The odds were against Volkswagen; the last German takeover, in 1939, had turned Skoda into a Nazi munitions factory. Populist-minded politicians (including the future prime minister, now president, Václav Klaus) wondered about selling “to Germany” so soon after escaping “Russia.” Volkswagen executives knew they could not outcharm the French executives, but whereas Renault offered to turn Skoda into a modern assembly plant, Volkswagen offered to invest in the Skoda brand.

“This was the point so many early investors missed,” says Charles Paul Lewis, the author of an insightful new study on the former Communist bloc titled How the East Was Won: The Impact of Multinational Companies on Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union (Palgrave-MacMillan, 2005). “The Czechs didn’t want Renaults, not really. They wanted Skodas with Volkswagen quality.”

A deal was signed on April 16, 1991. Volkswagen guaranteed jobs and a $5.7 billion cash injection. It also agreed to pay $416 million for a 31 percent stake in the company and two further payments of $260 million each in 1993 and 1994 to gain a 70 percent share. (It bought the outstanding 30 percent from the Czech government in 2000.) In return, it received full control of Skoda, with a complete debt write-off, tax breaks, and assistance with currency conversion. (A separate deal, which did not include Volkswagen, was made for Skoda Plzen, the industrial sister company that makes streetcars and other mass transit vehicles. Skoda Plzen is only now finding its footing in the free market after a series of blunders, shady dealings, and bad debts. For example, the government of Iraq owes it a lot of money.)

Skoda was the first major privatization deal in Eastern Europe — and, political and automotive analysts agree, the best. The price was fair. The terms were transparent and mutually beneficial. “It was the perfect foreign investment paradigm,” says Mr. Lewis. “Western money and know-how meets cheap Slav labor and market share.” The manner in which the deal was struck was as important as the terms. “All the decision makers were in the same room, and because it was the first privatization, the laws could be written as they went along,” he says.

Volkswagen’s early bets in Eastern Europe were seen as risky — the equivalent of pouring $10 billion into shaky state enterprises in Ukraine today — but the company benefited greatly from them. Today, it is the largest exporter in Slovakia, and one of the largest in Hungary. “The story of carmaking in Eastern Europe since 1989 is the story of Volkswagen,” says Mr. Lewis. VW’s executives also understood the value of diversifying beyond the former East Germany; then-weak currencies such as the Czech koruna lowered the costs of workers, infrastructure, and materials. Even if Skoda had struggled, Volkswagen would have profited from the dramatic value — as much as 100 percent — that the koruna has gained against the American dollar since the early 1990s.

Undoubtedly, Volkswagen also coveted Skoda’s 35 percent market share in Eastern Europe. Behind the iron curtain, from the Baltic Sea to the Adriatic, a Skoda was an aspirational purchase.

When they arrived, Volkswagen executives found Skoda disoriented, unmotivated, overstaffed, and undercapitalized. After some false starts, with ill-advised proclamations of company values that sounded too much like Communist exhortations, German executives realized that the future of the company lay in its past. “Workers were frustrated with Communist slogans,” says Jaroslav Povsik, a member of Skoda’s supervisory board and head of its unions, but they were aware of Skoda’s long-standing tradition of industrial craftsmanship. In its brochures Skoda began to include pictures of its distinctly bourgeois early roadsters, purring down Fifth Avenue in New York, and of the blue limousine in which the prewar president Tomas Masaryk rode. A company museum was built. To foster pride, there were parades and factory tours.

Like many other companies making acquisitions in former Communist enterprises, Volkswagen had to divest Skoda of its immediate past. That meant clearing out managers compromised by Communist Party or secret police connections as well as divesting the utility plants, transport depots, housing, kindergartens, libraries, and sports stadiums that the company had taken care of under Communism. The Germans trod carefully, appointing a Czech, Ludvik Kalma, as CEO. They introduced a system of tandem management, rotating in German managers for several-month stints to work alongside their Czech counterparts. To overcome the language differences, Volkswagen set up the largest language school in the country. Czech managers needed to speak German or English to advance (German managers were not expected to learn Czech). Enough managers developed a rapport across the language and cultural barrier for the Volkswagen methods to take hold at Skoda. “I can’t think of a single decision which was influenced by bad blood between the Germans and the Czechs,” says Mladá Boleslav’s mayor, Svatopluk Kvaizar.

Tensions were highest, however, in the early years, as Volkswagen cut production, laid off workers, and slashed its promised investment from $5.7 billion to $2.5 billion. There was posturing from the Czech government and from Volkswagen, which hinted it might move to Mexico. “There were tough moments,” says Mr. Povsik, “but the deal was never in doubt.”

Then Volkswagen’s investment paid off rapidly, with the launch in 1994 of a new compact model called the Felicia. The Felicia was a bridge vehicle between Communism and capitalism. It had a more appealing design than the Favorit: larger windows, a more modern-looking grille, and an interior that resembled those of the Volkswagen cars that Eastern Europeans admired but could not afford. Under the hood, however, the Felicia and Favorit were identical. In 1996, Skoda launched the Octavia, its first fully post-Communist vehicle. The midsized hatchback reminded the then head of Skoda technical development, Wilfried Bockelman, of “English understatement and a quiet drive in an autumn landscape.” The Octavia was also the first Skoda to turn the tide of jokes.

It had a bittersweet introduction. In November 1996, Ludvik Kalma was killed on a country road. He was test-driving an Octavia at twice the posted speed limit when he drilled into a truck stalled at a junction. The German weekly Der Spiegel speculated that Mr. Kalma might have been assassinated. It was still common to see such suspicions aired in the Czech Republic, where so many people with connections to the old regime had subsequently turned up as wealthy businesspeople. A Czech police investigation dismissed the murder claims. There was something singularly melancholy, all the same, about the chief executive of a car manufacturing company being the first person to die in the model that would assure his company’s fortunes.

Skoda’s Evolving Strategy

Mr. Kalma was succeeded by Vratislav Kulhanek, then the CEO of Bosch Czech Republic, the division of Bosch that made engines for Skoda. A onetime professional volleyball player, rally driver, marathon runner, and ice hockey fanatic, and a natural salesman throughout his career, he cut a flamboyant figure at Skoda. He was also the last Skoda CEO with a Communist pedigree; since the 1960s, he had been a salesman and financier for Czechoslovakian automotive suppliers. Having joined the Communist Party for, he says, “pragmatic reasons,” Mr. Kulhanek was kicked out with several hundred thousand others for opposing the 1968 Soviet invasion. Then, in the 1970s, because of his charm, he says, the Czech authorities allowed him to travel regularly to West Germany to conduct business. After the revolution, his name was found in the files of the national secret police (Statni Bezpecnost, or StB) as an informer. Mr. Kulhanek says it was placed there to smear him, a common practice of the StB. An investigation by Volkswagen failed to turn up anything that would prevent his succeeding Mr. Kalma.

Skoda was increasingly assertive on Mr. Kulhanek’s watch, in part because of the CEO’s rare ability to speak with equal persuasiveness to Volkswagen executives (in fluent German) and to Czech assembly-line workers (in his native Czech). Mr. Kulhanek oversaw the introduction of an award-winning replacement for the Felicia called the Fabia (1999) and of the new Octavia (2004), which won the Golden Steering Wheel award in Germany and was voted Most Beautiful Car in Italy. He fought VW for the right for Skoda to produce a limousine model called the Superb (2002). And he convinced VW to make Skoda the rally driving representative for all the VW brands. “It’s about visibility,” says Mr. Kulhanek. “Rally driving is expensive. But it’s worth it.”

For all of his success, it is hard to escape the feeling that there were sighs of relief in Wolfsburg when Mr. Kulhanek retired as Skoda’s CEO in 2004. (He still heads the national automotive and industry associations as well as serving as chairman of Skoda’s supervisory board.) The Superb had ruffled feathers in Germany. It was well received by the critics, but it too closely resembled the Passat, Volkswagen’s executive workhorse. Skoda began drawing customers from the Passat in Britain, for example, after a J.D. Power and Associates survey placed the Czech automaker second in customer satisfaction to Lexus, with Volkswagen nowhere in sight. Skoda’s success thus potentially endangered Passat-related jobs in Germany. That was unthinkable for Volkswagen, which, with its partial state ownership and powerful unions, has sometimes been accused of trading profit for job security.

“It’s not just a problem between Skoda and Volkswagen,” says Dave Leggett, managing editor of www.just-auto.com, an industry Web site. “How to maximize efficiencies while managing brands is a question for the whole industry. Ford doesn’t want buyers to know that its Jaguar X-type uses the same platform as the common Ford Mondeo.”

Volkswagen’s response has been to rethink its brand definitions. The Audi, Seat, and Lamborghini brands are now known as “sporty” within the company; Volkswagen, Skoda, Bentley, and Bugatti are deemed “conservative.” The problem of growing Skoda, but not at the expense of other Volkswagen brands, has fallen to Detlef Wittig. A Wolfsburg stalwart and the first German to head Skoda, Mr. Wittig has a trim build and a moustache that make him look younger than his 62 years. His post as Skoda CEO is the culmination of a long career at Volkswagen (beginning in 1968, and including a 1975–77 stint as Volkswagen’s representative in Japan). And he was not a stranger. From 1995 to 2000, Mr. Wittig served Skoda as the head of sales and marketing; he was remembered for having said, at the 1996 launch of the Octavia, that Skoda had passed a milestone: “It is now a normal company; not excellent, but normal.”

|

|

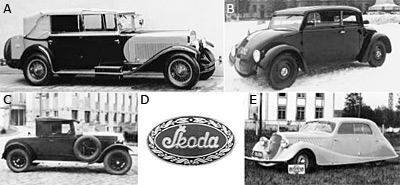

A Skoda’s 1929 luxury car, the 860; only 49 were ever manufactured. B The hood of a 1932 Skoda prototype anticipated the future Volkswagen Beetle. C The Skoda 110 roadster, produced in 1925. D This Skoda badge appeared on the front of cars from 1925 until the early 1930s. E The Skoda Superb, circa 1937; the Superbs of that era were hand-built to the specifications of wealthy customers. |

|

|

F The Skoda Trekka, an all-terrain vehicle manufactured starting in 1966 by Skoda for export to New Zealand, was offered in yellow, blue, red, and green. G The Skoda 130 RS sports car confounded Communist stereotypes by winning the 1981 European Championship for manufacturers. H-K Four contemporary Skoda models, aimed at its new global markets: (H) the Octavia, 2004; (I) Felicia, 1999; (J) Fabia, 2005; and (K) Yeti, concept car, 2005. All photographs courtesy of Skoda. |

One other factor made him a likely candidate for the top position. Mr. Wittig was born in 1942 in Magdeburg, a town that was swallowed up a few years later into East Germany. If his parents had stayed in Magdeburg, Mr. Wittig would have grown up under Communist rule. This sensitivity helped him approach the Czechs as equals. “He understands the Czech mentality,” says Mladá Boleslav Mayor Kvaizar, who has worked closely with Mr. Wittig on town–company relations. “His negotiating style is open and straightforward.”

During his first year as CEO, Mr. Wittig’s work ethic and transparent manner have built up their own following in Mladá Boleslav. “He is making up for Skoda’s lost time,” says one colleague. Mr. Wittig agrees. “My heart is at Skoda,” he says. “We’ve paid off our debts. We’re ready to go. Our financial results mean we can widen our production and our market base.”

The Volkswagen brand will now migrate up-market (a declaration made with the 2004 introduction of the opulent Volkswagen Phaeton), and Skoda will seek to dominate the base of the pyramid. In effect, Volkswagen has handed Skoda the task of creating a global equivalent of the original VW Beetle, with sufficient quality and innovation to avoid being undercut by cheaper carmakers from other emerging countries. Renault, for example, has recently taken a 93 percent stake in Romania’s leading automaker, Automobile Dacia, with the intent of turning it around. “There will always be cheaper carmakers,” Mr. Wittig says. “I’m not interested in them. We have to stick to our concept. A Skoda can only be stripped down so far. We are not going to produce bloody tin boxes.”

Mr. Wittig’s target is to increase production to 600,000 vehicles over the next few years, or about 12 percent of the Volkswagen Group’s volume. One possible stumbling block is morale. Although Skoda’s directors are all German, the number of German executives has dropped from 400 in the early 1990s to 40 today — and roughly the same small number of Czech executives have been promoted to positions in the Volkswagen Group. Resentment is growing among Skoda workers at the gap between their salaries and those of people doing the same work across the border at VW plants in Wolfsburg — about $1,000 a month in the Czech Republic compared with $4,000 a month in Germany. There were mass marches and strike threats in Mladá Boleslav in April 2005. Union leaders are cautious about possible damage to Skoda, but believe continued action will build awareness. “It has to change,” says Mr. Povsik, the union head. “The gap in wages is not going to be defensible forever now that the Czech Republic has joined the E.U.”

The current scandal will also complicate labor relations — and perhaps instigate change — at both Volkswagen and Skoda. Involving allegations of bribes made by company executives to labor officials, the scandal had resulted by July in the abrupt resignations of Helmuth Schuster, Skoda’s head of human resources, and Klaus Volkert, the top labor representative at Volkswagen.

Even if Mr. Wittig gets the positioning, labor relations, and crisis management to come out right, the promise of expansion foretells an uphill struggle. Skoda’s 48 percent market share in the Czech Republic makes it vulnerable at home. “As Czech consumers become more affluent and savvy, they will look at more expensive brands,” says Mr. Leggett. More competition will soon arrive when a new $1.8 billion assembly plant east of Prague starts to churn out its annual target of 300,000 Toyota, Citroën, and Peugeot cars. A bigger problem is the way E.U. enlargement has opened up the used-car market in the Czech Republic and neighboring Poland. Czech sales plummeted 10 percent in 2004, and Polish sales 12 percent — with most of the loss attributable to used-car dealerships. “We have to pay attention,” says Mr. Wittig. “Eastern Europe mustn’t become a place for scrap from Western Europe.”

Where then to expand? The car market in Western Europe is mature. Analysts predict only small growth there in the next 10 years. Yet with just 3 percent market penetration in Germany, Mr. Wittig thinks there is plenty of room for Skoda to grow, particularly at the expense of Ford and GM. The company is also seeking to compete with Fiat in Italy and elsewhere in Europe. Skoda signed on recently as a main sponsor of the Tour de France, which is said to be the third most-watched sporting event in the world, after the Olympics and the world soccer championships. Skoda is moving aggressively into Ukraine (where a Skoda plant has been profitable and Western-leaning Ukranians are fond of the cars) and Russia (where Skoda has lost money so far). Skoda’s Ukraine strategy has already proven successful in Serbia: First, sell fleets of Skodas to police and other public institutions, then sell aggressively to the nascent middle class.

Farther afield, Mr. Wittig says he wants to expand assembly production at Skoda’s Aurangabad plant in northern India to take advantage of the company’s luxury image. Mr. Wittig rules out direct investment in China, favoring instead the idea of licensing the Octavia to a Chinese automobile company.

In short, the kind of growth to which Skoda has already committed itself is possible only through leapfrogging: breaking away from conventional industry assumptions (and their costs) in marketing as well as in operations. And Skoda is attempting a similar leap in design as well.

Emulating Ikea

“The success of Skoda came step by step,” says Mr. Wittig. “Volkswagen brought the company up to date, but it was a fully functioning carmaker long before the Communists ruined it. It made beautiful cars.”

It certainly did. Some of them are now in the company museum in Mladá Boleslav: sleek limousines and roadsters in cream, tomato, black, and cobalt, all of them with Skoda’s trademark bulging chrome grille. The man presently charged with rebuilding that design sense, while staying within a price range that emerging members of the middle class can afford, is Thomas Ingenlath, chief of design. A young design talent at Volkswagen before coming to Skoda, Mr. Ingenlath was known for the concept cars he created for Bugatti. Now he is producing designs for younger buyers, like the new Octavia introduced in 2004. Mr. Ingenlath is currently the most visible advocate within Skoda for the company’s becoming “the Ikea of carmaking.”

The Ikea approach will be tested with the launch of the Roomster model in 2006. Like other Skoda models, it is targeted between two traditional class sizes, in this case between a station wagon and a minivan. “It’s something the young will want to buy,” says Mr. Wittig.

The freedom Volkswagen gives Skoda on design issues is significant. Mr. Wittig is passionate about research and development. Why else, he says, would Skoda bother to build an “innovation campus” for 1,300 designers and engineers next to its main plant? “We can’t develop everything in a car,” says Mr. Wittig, “but we will continue to develop in Mladá Boleslav [the features that make] a Skoda original. That means electronics and design features.” The company has built a Skoda university (offering degrees to prospective and present workers in business and technical disciplines) to “make sure our workers receive a Skoda education as well as a state one,” says Mr. Wittig. Skoda spent $210 million on research and development in 2004.

Skoda’s leaders have tied their fortunes to their faith that enough of a middle class will emerge around the world to be able to afford their cars. That may have seemed like a risky bet in the 1990s, but now it looks certain to pay off. To win over those customers, Skoda uses the same marketing weapon that Volkswagen itself used when it first launched the Beetle in the United States. That weapon is humor. Television slots had Skoda poking fun at itself and pitching the car as the choice of the underdog. “That helped establish us,” says Winfried Vahland, Skoda’s finance chief and vice chairman. “Now we need to concentrate on emotional efforts to enhance the brand.” In other words, future advertising campaigns will focus on the driver, not on the car.

Ice hockey, the Czech national sport, has been the other consistent feature in Skoda’s marketing campaign. “Ice hockey has the qualities of speed, precision, and teamwork Skoda wishes to be associated with,” says Mr. Kulhanek, who also presides over the Czech ice hockey association. Skoda now dominates corporate sponsorship of European ice hockey. Václav Havel joked that he couldn’t tell the Czech team from the American team at the 2004 World Championships, held in Prague. “It looked like Skoda versus Skoda to me,” he said at the time. The wisecrack did not endear the retired Czech president to Mr. Kulhanek, who scolded him for a lack of loyalty to the national corporate flagship. Yet many Czechs laughed along with Mr. Havel. That in itself showed how much things had changed. There was no inferiority complex; Skoda was successful enough to take a joke — and no longer in danger of becoming one.![]()

Reprint No. 05306

Jonathan Ledgard (jonathanmagnusledgard@yahoo.com) is a foreign correspondent for The Economist and a contributor to The Atlantic Monthly. He writes about politics, war, and environmental issues. His profile of Danish “new optimist” Bjorn Lomborg appeared in the Spring 2005 issue of s+b.