Hyundai’s Capabilities Play

The Korean automaker’s explosive growth in the last few years — achieved through better quality, stylish design, and clever marketing — has made it a dynamic player in the U.S. auto industry.

(originally published by Booz & Company)Anyone looking for an explanation of the Hyundai Motor Company’s approach to the U.S. market—which has brought it from a near collapse in sales in 1998 to controlling 5 percent of the market today—might start with the third door on the Veloster hatchback. This sporty car, aimed at people under age 35, sells for a starting price of around US$20,000. It’s an idiosyncratic car, with the look of a sleek, friendly shark; it also has a single door on the driver’s side, but two doors on the right.

The third door, whose purpose was to improve access to the back seat for passengers or cargo, was originally conceived as a purely pragmatic feature. Then, as part of an internal face-off, two design teams—one at Hyundai’s design and engineering center in Ann Arbor, Mich., and the other at Hyundai Motor America headquarters near Los Angeles—were assigned to build prototypes. The Michigan team proposed two doors on the same side opening in opposite directions—an otherworldly, appealing design. But as the California team pointed out, a passenger stepping out of the car would not see traffic coming up behind the door. The Californians bestowed the nickname “suicide doors” on their rivals’ offering, and suggested instead a more conventional parallel design, but one that placed the handle in an unusual corner position, which enhanced the car’s funkiness and flair.

The California door won the approval of top management; the Veloster sold out soon after launch in January 2012, and remained sold out during most of the year, bolstering Hyundai’s reputation for fashion-forward, inexpensive automobiles. A more powerful turbo version was introduced in September. “There’s an acknowledgment by many designers right now that Hyundai has the hottest design in the industry,” says Joe Philippi, president of AutoTrends Consulting LLC of Short Hills, N.J.

Hyundai’s prowess in design, product launch, and consumer awareness is part of a distinctive model of product management that this $66 billion, family-owned and -run car company has only recently brought to fruition. The Korea-based enterprise, regarded in the 1990s as a purveyor of cheap, low-quality cars and in the 2000s as a “me-too” follower of Toyota and Honda, has since become the fastest-growing automotive brand in the United States. In 2011, according to the consultancy Interbrand, the only companies that improved their brand recognition more were Google, Apple, Amazon, and Samsung. Hyundai sustained an impressive performance in Interbrand’s 2012 evaluations. And a jury of 50 automotive journalists named Hyundai’s Elantra sedan the 2012 North American Car of the Year, beating out Volkswagen’s Passat and Ford Motor’s Focus. Other Hyundai offerings, such as the Genesis Coupe and Sonata Hybrid (an angular car with two panoramic sunroofs) have had similarly positive receptions.

Hyundai has been able to step out from behind its larger Japanese competitors and stake a claim to style leadership in part because of the culture of creativity that it has fostered, in which U.S. employees and Korean executives innovate together. “Hyundai doesn’t cede as much control to the Americans as Toyota does,” says Ed Kim, who worked at Hyundai for four years and is now vice president of industry analysis for AutoPacific Inc. in Tustin, Calif. “The Koreans remain very much in control.”

But at the same time, Hyundai has learned how to encourage local teams—in this case, U.S. teams—to go out on a limb and compete in search of ambitious and unconventional solutions. The combination of central control and local responsiveness has given the company an ability, now embedded in its culture, to pick up local signals and rapidly turn them into product designs. Managers speak of working at “Hyundai speed.” This has enabled the company to release 21 new North American models in five years, including a new luxury sedan called the Equus.

Hyundai is also recognized for its ability to spread design features among its product lines. It routinely moves technological features from high-end luxury automobiles into much less expensive vehicles. Push-button ignition, rear-vision video monitors, and automatic headlights—features that once appeared only in high-end marques such as Mercedes and Cadillac—are now widespread on Hyundai vehicles costing $20,000 to $30,000. This means, of course, that the company has to keep improving its more expensive cars or their sales will be cannibalized. And even though the company is pouring such expensive “content” into its vehicles, it enjoys an estimated 9 to 10 percent profit margin, which is considered high in the auto industry. The company achieves those margins partly because it limits promotional discounts for buyers in the industry; the cars are sufficiently in demand that the company doesn’t currently need incentives to persuade buyers. It also boasts the best fleet fuel efficiency, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and the best ownership repurchasing rates, a key test of loyalty, according to J.D. Power and Associates. “We’ve got the whole package right now,” says executive vice president Frank Ferrara at Hyundai Motor’s North American sales headquarters in Costa Mesa, Calif.

Some observers suspect that Hyundai’s recent successes may be anomalies, abetted by the difficulties that the company’s U.S. and Japanese competitors faced after the global economic crisis, the rise in the yen’s value, Toyota’s wave of recalls, and the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan and Fukushima nuclear disaster. Others say that the company’s highly protected home market has enabled its growth, allowing Hyundai to establish a global presence while its domestic competitors restrict themselves to tiny slivers of the Korean market.

But the single factor that has made the most difference is the company’s own interest in building world-class capabilities. Starting in 1998, Hyundai’s leaders set out to develop the kind of prowess the company would need to become a global automobile powerhouse, able to hold its own in the United States and other fiercely competitive markets. Early on, that meant offering a comprehensive warranty and taking specific steps to dramatically improve its quality ratings. Once customers were convinced of the brand’s reliability, Hyundai added other capabilities, such as design, which led to a more diversified product line and more stylish features. Meanwhile, it developed a knack for getting the word out through clever, consistent marketing.

The result is a coherent mix of quality improvement, design, and marketing that gives Hyundai a clear advantage over its industry competitors. Although these are required capabilities at all automakers, Hyundai has excelled at combining them over the past decade, and its sales numbers reflect this success. The company’s effort to become a world-class automaker is beginning to pay off, and it’s far enough along that its story can be credibly told.

The Quality Edge

No matter how big and global it becomes, Hyundai will always rightfully be seen as a Korean company in its business culture and operating style. The company’s founding brothers, Chung Ju-Yung and Chung Se-Yung, endured the devastation of the Korean War after fleeing to South Korea from North Korea in 1947. They began their career by forming a construction firm; in the 1960s they expanded, opening first a repair shop and then a machine shop. All along, the Chungs were determined to build a chaebol, or industrial consortium of allied companies. (Patterned in part on the Japanese keiretsu model, these family-owned consortia are dominant in the South Korean economy.) The Chungs soon revved up companies in steel, shipbuilding, and construction. They started Hyundai Motor Company in 1967 and launched their first car, the Cortina, in 1968.

Hyundai Motor confined itself to Asian markets until 1986, when it released its first U.S. model, the Excel subcompact. At first, thanks in part to cheap Korean currency and technology borrowed from the Mitsubishi Motors Corporation, the car sold well; Hyundai still holds the industry record for most U.S. sales (186,000) during its first year of business. The low price of its cars and the company’s marketing savvy overcame local unfamiliarity, as well as the fact that potential U.S. customers struggled to pronounce the company’s name. (The company eventually told customers that Hyundai, which means “modernity” or “technology” in Korean, rhymes with the English word “Sunday,” even though the Korean pronunciation is considerably different.)

But the company’s mentality was still focused on pounding out units and increasing sales volume. Hyundai’s purchase of Kia Motors Corporation in 1997 and the Asian currency crisis in 1998 gave new urgency to the need to shrink expenses, and the company cut back on quality efforts. Sales dropped dramatically, and in May 1998, only 4,200 Hyundai cars were sold in the United States. “Many of us were pretty sure we were about to go out of business,” recalls Ferrara, who was then vice president for parts.

The solution turned out to be a new focus on quality—starting not with manufacturing, but with a marketing initiative. As the company recounts it, in 1998, facing the huge drop in sales, Hyundai’s U.S. executive leaders commissioned a bout of desperate consumer research. They discovered a highly positive reaction to the prospect of a three-part warranty deal—10-year and 100,000-mile powertrain protection, five-year/60,000-mile bumper-to-bumper coverage, and five-year/unlimited mileage roadside assistance. They proposed calling it “America’s Best Warranty.”

The warranty was less of a risk than it probably seemed to outsiders—for example, the powertrain part of it would not transfer to a new owner if the car was sold—but it still represented a massive bet on the company’s ability to improve. If car quality didn’t go up dramatically, the company could be crushed in an avalanche of claims and bad publicity.

Chairman Chung Ju-Yung was dying, and his brother Se-Yung was running the auto company. Se-Yung approved the new warranty strategy on a car ride from the Los Angeles airport to his hotel, basing the decision on his gut instinct. Ferrara, who had recently come to Hyundai from Toyota, remembers this snap decision as clear evidence of the difference in his new company’s culture. “The Koreans are cowboys and very different from the Japanese,” he says. “At Toyota, it would have taken 18 months to get the idea through the consensus process.”

In itself, the decision didn’t guarantee that the company would actually be able to make cars of sufficient quality to avoid a warranty bloodbath. It might not have worked out, except for the arrival of a new chief executive. Chung Mong-Koo, the oldest of Chung Ju-Yung’s eight sons, took over the motor company in 1999, elbowing Se-Yung aside to become chairman and CEO.

“The chairman,” as Chung Mong-Koo is still referred to inside Hyundai, had started his career in the corporation’s industrials division, moved to iron and steelmaking, and then worked for 11 years at Hyundai Motor Service, which focused on repairs and follow-up service. Chung thus had seen the consequences of poor quality firsthand. He decreed that the company would now put product excellence first. To enforce this, he set up a new quality division that could intervene at any stage of design, engineering, or production. Chung, who did not speak English, would visit U.S. plants with an interpreter. He would personally take executives out of their offices and walk them to a hoisted-up car and point out problems, such as a door that didn’t always close properly.

Ferrara recalls a visit the chairman made during this period to a parts distribution center in Ontario, Calif. He walked through the building and noticed a large pile of remanufactured transmissions, which had all failed initially and needed to be rebuilt. “He immediately called for everyone associated with transmission design and quality to assemble in California as soon as possible,” Ferrara recalls. “We had about 20 high-level executives from all related divisions fly in from Korea within 24 hours.” To fix the problem, the company ultimately decided to bring all its transmission design and manufacturing in-house, an unusual move in an industry that was increasingly outsourcing complex assemblies to suppliers.

As part of their quality effort, Hyundai executives in both Korea and the U.S. studied their competitors, tearing apart their vehicles and adopting their best practices. This led them to rediscover statistical process control and other techniques of quality management, and to resuscitate some of the ideas about systems-oriented management and customer awareness that W. Edwards Deming had originally championed decades earlier, and that other car companies had long been following. For example, when Hyundai executives studied automotive quality indicators to determine how best to catch up to Toyota and Honda, they found that many companies downplayed the customer satisfaction reports of Consumer Reports and initial quality reports of J.D. Power. So Hyundai created a combined metric called “qualativity,” which includes quality, productivity, and customer satisfaction. Hyundai still uses this hybrid concept to measure everything that happens in one of its car plants. “It’s a uniquely Korean approach,” says Chris Susock, director of quality operations at Hyundai Motor’s manufacturing plant in Montgomery, Ala., where the compact Elantra and midsized Sonata sedans are made.

Hyundai also made a big technology bet to support its quality drive. It created the Global Command and Control Center in Korea, which is reminiscent of a U.S. Strategic Command war room, its walls covered with television screens and computer monitors. The company shares little about the center, and treats its secrets as a vital source of competitive advantage; Hyundai will not even reveal the year that it was founded. But some facts are public knowledge. For instance, the center monitors every operating line at 27 plants in the world, in real time, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. The production data is generated on the assembly lines and displayed on boards where team members can see it, and headquarters can see the same data at the same time. If the quality monitors spot errors or problems, they call the factory immediately. “If there’s a hiccup at any of those boards, headquarters wants to know what needs to be done about it—right now,” says the Alabama plant’s production chief, Ashley Frye.

Though Chung Mong-Koo was the prime mover in setting up the quality goal, and personally involved in driving it, company veterans credit Hyundai’s organization with rapid bottom-up response. “The chairman decreed, ‘Within this period of time, we will have the same quality as Toyota,’” recalls AutoPacific’s Kim. “Whenever the chairman makes a decree, there is a very impressive mobilization to make it happen. It’s a Korean cultural thing. The company mobilized and made it happen with breakneck speed.”

Hyundai’s efforts to improve quality have intensified during the 2000s. For example, visitors to the Alabama plant are greeted by banners proclaiming: “Hyundai aims for GQ—3.3.5.5.” This cryptic message refers to the company’s goal, announced in 2009, of becoming one of the top three automakers in empirical global quality measures within three years, and one of the top five in perceived quality within five years. (Customers’ perceptions of quality generally lag behind actual quality, hence the different time frames.) If this sounds like a challenge to Toyota, that’s the intent—with an eye toward raising resale value, which makes customers more willing to spend more money on new cars.

To keep improving the quality of its vehicles, Hyundai continually experiments with technological process advances. For example, Frye and deputy plant manager Craig Stapley carry smartphones that display performance information about each assembly line as well as the welding and paint shops. In an environment where information is ubiquitous and instantly available, quality problems are quickly flushed out. Every vehicle is tracked from inception to final sale.

“All of the people I meet at Hyundai are hell-bent on making sure the quality is getting better all the time,” says Michael Dunne, a noted expert on the Asian auto industry, based in Hong Kong. “This special mind-set, which works particularly well with companies on the way up, says that ‘we will be best at what we do, wherever we go and whatever it takes.’ It makes incumbents seem flat-footed by comparison.”

The quality emphasis is visible in Hyundai’s manufacturing plants, such as the one in Alabama. Its level of vertical integration is rare in the industry; coiled rolls of steel are welded into bodies on-site; engines are also built there. The factory’s F-shaped assembly line allows trucks to pull up and deliver parts where they’re needed; electronic data links to suppliers help track customized parts and ensure they match.

The factory was designed to produce 300,000 units a year, but volumes have been running above that; it made about 345,000 vehicles in 2012. The plant has been running flat out since 2010, and workers have been putting in as many as 60 hours per week, which is considered a burnout rate at most car plants. The pace is possible in part because the workers tend to be younger than the average worker at U.S. company plants—and even younger than workers at Japanese-owned plants in the United States. Hyundai added a third shift in August 2012 to ease the pressure.

The entry-level wage is $16.25 an hour, rising to $25 an hour after two years, which is modest by international standards but generous in the depressed Alabama economy. Workers rebuffed an effort by the United Auto Workers (UAW) to organize the plant. Reflecting Japanese-style lean manufacturing, the plant is managed in a horizontal, egalitarian fashion. Everyone eats in the same cafeteria. No cursing is allowed.

Although the original Hyundai chaebol was broken into three groups, the Hyundai Motor Group still includes 42 companies, and it leverages those connections energetically. Known as Hyundai Motor, this consortium includes the smaller automaker Kia, parts maker Mobis, logistics specialist Glovis, financing company Hyundai Capital, and Hyundai Steel. Hyundai is also the only automaker in the world to produce its own steel. Chung Mong-Koo has personally been involved in supervising the construction of an $8 billion steel complex about 90 minutes southwest of Seoul on the Yellow Sea, which is now nearing completion. Hundreds of engineers are assigned there to find ways of making better steel so that Hyundai cars can become lighter and more fuel-efficient. Visitors describe the docking of Hyundai ships carrying iron ore from around the world. Workers laboring around the clock use conveyors to transport the materials into two giant indoor domes. “It’s like visiting the Grand Canyon,” says new North American design chief Chris Chapman, a recent recruit from BMW. “That is where you sense the scale of this company.”

Hyundai’s plants in the U.S., including Alabama, use chaebol companies as suppliers but are not limited to them. This is a key to understanding how the company operates. The Alabama plant also buys from some non-chaebol Korean companies that have traditionally supplied Hyundai; Daechung, Guyoung, Smart, Hwashin, and Sejong have all set up businesses in Alabama to supply components. The plant uses Lear for rear seats, PPG Industries for glass, and Continental, a German company with a plant in Illinois, for tires. Overall, it has 80 suppliers in the U.S., Canada, and Mexico, including 28 Korean companies that have established North American operations. By encouraging robust competition among group suppliers and non-group suppliers, Hyundai avoids being obligated to do business with an internal supplier that is not up to global standards, but it keeps its chaebol relationships intact.

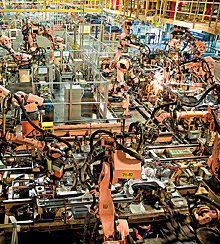

In general, Hyundai seeks to establish deep long-term relationships with its suppliers and examines their manufacturing processes to help them improve quality at a lower price. “My suppliers are part of the family,” says David P. Mark, head of parts purchasing. The stability and quality of the supply base enable suppliers to create modular subassemblies, reducing assembly time on the Hyundai line and decreasing the possibility of human error. The plant also makes extensive use of robots; as a Sonata comes down the line, for example, a robot twists and grabs a complete dashboard, then twists it again and installs the dashboard in the Sonata. What would take two people half a minute takes just a few seconds. As a result, the Sonata is built in fewer hours than any other midsized car on the market. This ultimately helps Hyundai set aggressive price points for its vehicles at the same time that it maintains high profit margins.

Design and Innovation

Chung continued to push the quality initiative through the mid-2000s, but as the company grew more capable, he began to set out other major goals, launching them once again with initiatives from the top. One was design. In an age of cost cuts and customer focus groups, most car companies had settled on a few familiar, pragmatic, aerodynamic shapes for their sedans. The design process at companies such as Toyota, Honda, and GM was consensus-driven and familiar; the designers themselves were aging. Chung and his team felt that consumers were getting tired of incremental changes to the same basic look. This was a major step for a company that had sometimes suffered criticism for having derivative designs.

Chung began by quietly seeking out top-level design talent in Germany, Italy, and the United States. Then, at the Los Angeles Auto Show in December 2009, he proclaimed that Hyundai would adopt a new design approach called “fluidic sculpture,” inspired by natural shapes. To many observers, this was a signal that Hyundai would no longer follow the bland styling cues of the rest of the industry.

Two aspects of Hyundai’s workplace culture helped the company create edgier, more distinctive cars. First, its designers were younger. “Design is a young-minded person’s business,” says design chief Chapman, who is based in Irvine, Calif. “We’re in the business of making people feel young.” He says the design teams he inherited, consisting of both Americans and Koreans, display “fearlessness” in their approach to design.

Second, the Koreans tolerate the kind of internal competitions that led to the Veloster door design—and they thus accept a level of conflict that would be anathema in a Japanese car company, where nobody likes to see anybody lose. At Toyota and Honda, after the dimensions and market segment of a new car are defined in the planning process, executives tend to lock in early on a design and rarely change it as the vehicle winds through the development process of three to four years. That means that designs may no longer be fresh by the time the car hits the streets.

John Krafcik, CEO and president of Hyundai Motor America—who previously worked for Toyota at its joint venture with GM in California called NUMMI and then for Ford Motor Company—takes a direct interest in building the company’s innovation capability, in part by setting stretch targets. “We often say, with a smile, we never set a target that we know how to hit,” Krafcik says. “We always under-resource our organizations, in terms of both head count and dollar operating budgets. The thing that fills the gap is innovation.”

Krafcik, the public face of Hyundai in the United States, is an unusual executive in an industry often characterized by bravado and swagger. He possesses two degrees: one in engineering from Stanford, the other in business from MIT’s Sloan School of Management. Despite his age (50) and gray hair, he still seems boyish. Yet he has succeeded in winning the confidence of Hyundai’s top brass in ways that his predecessors could not; a rapid succession of them had short stints at the company, but Krafcik has been with Hyundai since 2004, and he has been president of Hyundai Motor America since 2008. He offers an analytical perspective on one of the central riddles of Hyundai management: How does a top-down, hierarchical company manage to be as freewheeling and innovative as it is?

The key, he says, is that Hyundai excels in recognizing ideas that bubble up from U.S. designers and managers and embracing those ideas. The chairman has personally created a corporate culture that insists on innovative new ideas.

Krafcik also has been able to bridge the cultural gap with his Korean superiors and the coordinators the company assigns to key U.S. executives. These English-speaking Korean coordinators report directly to Seoul in the evenings, when the U.S. managers have gone home for the day. The common wisdom inside Hyundai is that a Korean coordinator’s day starts when a U.S. manager’s day is ending, at 5 p.m., because it’s early morning in Seoul and thus time for the coordinators to get on Skype with their counterparts back home and spend several hours hashing out issues. The coordinators, who often have been educated at U.S. universities and are thus more Westernized than their counterparts in Seoul, serve as a communications bridge and in some ways are the equals of the executives to whom they are assigned. The communication between them and the U.S. teams is not always smooth, but it’s far more engaging than the conventional approach in U.S. subsidiaries of Japanese companies, where a U.S. executive might speak to his or her Japanese superior only once every two weeks, often through a translator.

Krafcik’s subsidiary does not have full manufacturing or design responsibility, but it controls marketing and consumer relations. Besides the warranty deal, which still distinguishes the company from its competitors, the marketers have developed a knack for hooking customers who are considering buying a Hyundai, but need a way to rationalize the risks (along with the unfamiliarity of the company name). They met the 2008–09 recession with a campaign in which they offered to buy back new vehicles if owners lost their job. And they continue to focus on the kind of pragmatic, stylish, modest, and fuel-efficient cars that resonate with post-recession U.S. consumers.

What Happens Next

Building in large part on its North American success, Hyundai is rapidly moving to a global scale. The company now sells more vehicles in China than it does in the U.S., thanks to an aggressive expansion of manufacturing and design capacity there. Hyundai and its Kia brand are also charging into Europe. At the same time that Peugeot, Citroen, and nearly all other automakers are losing money in Europe—and suffering from a glut of excess capacity—new Hyundai and Kia dealerships are popping up throughout the continent. Together, they now make up the fifth-largest automaker in the world.

The biggest problem Hyundai faces in the short term is holding back on production to make sure that it continues to improve on quality. “I’m very proud that the company has made this decision to throttle its own growth,” says Krafcik. “Can you think of companies in any industry who have ever done that? We clearly have incremental demand in markets around the world, yet our company said, ‘We’re going to cap production this year at 7 million units.’” He estimates the company could have sold 10 to 15 percent more vehicles.

This type of move is possible only for a company with a long-term view. Already, the capabilities that Hyundai has built for itself have allowed it (along with a few other businesses, such as Samsung Electronics Company) to transcend the perception of Korean companies as purely low-cost producers. Hyundai’s executives expect to see the company’s brand position rise higher in the U.S. market because Hyundai is targeting younger, better-educated buyers with higher credit scores. Reflecting that demographic shift, Hyundai dealerships that once offered coffee and doughnuts to potential customers now serve cappuccino and croissants.

The goal obviously is to secure the company’s reputation for quality and set the stage for continued global gains. “We almost certainly will be better off 10 years from now by taking this pause in growth and solidifying our quality processes and getting the right customers,” Krafcik adds.

A central challenge is maintaining its entrepreneurial pace. The Koreans have pushed U.S. managers and workers very hard. Krafcik says he typically spends only a handful of evenings at home each month. It would be only natural to slow down the tempo. “We’ve had a period of success,” says Krafcik. “And it’s after a period of success like this that companies frequently go wrong. They make missteps. We are ever mindful of complacency and arrogance. We can’t relax.”

Another potential disruption on the horizon is that the chairman, Chung Mong-Koo, is 74 years old. His only son, Chung Eui-Sun, is vice chairman and boasts a master’s degree from the University of San Francisco. He speaks English well, and is gradually asserting more influence over how the company operates. But there is always a chance that when Chung Mong-Koo steps down, there will be a hard-to-fill gap in upper management.

In addition to these issues, the auto industry remains brutally competitive. Japanese and U.S. carmakers still wield huge power globally. Toyota, in particular, has Hyundai in its sights; it is now offering 0 percent financing, plus a $500 check, on some models. Toyota, which has cash reserves of more than $40 billion, can afford to virtually give away cars to regain market share—for a while. Its U.S. sales in September reflected that strength, surging 42 percent. Japan’s Big Three manufacturers—Toyota, Nissan, and Honda—are also signaling that they will move more production from Japan to other countries to counter the impact of the strong yen.

Krafcik can see the first glimmers that the Japanese will try to compete on the basis of design. When he attended the New York International Auto Show in April 2012, he extended his stay for a day to examine the more stylish, aggressive looks of the new Toyota Avalon and Nissan Altima. “This is not a game-over situation,” Krafcik says. “Folks are figuring out what we have done.” He is right to be looking over his shoulder. In the global auto wars, no one wins forever.![]()

Reprint No. 00162

Author profile:

- William J. Holstein is a contributing editor to s+b and author of The Next American Economy: Blueprint for a Real Recovery (Walker & Company, 2011) and Why GM Matters: Inside the Race to Transform an American Icon (Walker & Company, 2009).