The $112 Billion CEO Succession Problem

Poor planning for changes in leadership costs companies dearly. Getting it right is worth more than you might think. See also “CEO Succession: Why It Pays to Have a Plan.”

Costs can mount quickly when the chief executive officer of a large company is fired or departs suddenly without an obvious internal replacement. The typical seven-figure severance package and six-figure retainer for an executive search firm are just the beginning. Board members might have to fly in on short notice for an emergency meeting. A small army of professionals — all of whom charge by the hour — begins to mobilize: communications consultants and employment lawyers, movers and relocation experts. The longer the clock ticks, the higher the figure on the meter.

And those are just the hard, easily quantifiable impacts. They pale in comparison to the less visible costs. Turmoil and uncertainty at the top filter quickly down through the organization, slamming the brakes on growth initiatives, hindering the closing of vital deals, and causing some valued employees to start looking for new positions elsewhere. Because unexpected successions can paralyze even the best-functioning companies, they can wreak a harsh toll on revenues, earnings, and stock prices.

This year, in the 15th Strategy& annual study of CEOs, Governance, and Success, we focused on CEO succession as a business issue: How much is it worth to get it right, and what is the cost of getting it wrong? The answer to both questions: a lot. Large companies that underwent forced successions in recent years would have generated, on average, an estimated US$112 billion more in market value in the year before and the year after their turnover if their CEO succession had been the result of planning. That’s a lot of money. Even in cases where successions are planned, financial performance suffers in the year before and the year after the change (see Exhibit 1). In other words, there’s always a cost to changing leadership at the top, but companies pay a much bigger price when they get into situations that can be resolved only by forcing out their CEO.

CEO Succession: Why it Pays to Have a Plan

Watch this video to see why large companies can lose billions of dollars when they don’t plan for changes in leadership.

We also looked at the correlation between total shareholder returns and succession characteristics over our entire data set from 2000 through 2014, and found that underperforming companies tend to have more forced turnovers, outsider appointments, and multiple successions. (See “Succession Planning and Financial Performance.”)

Underperforming companies tend to have more forced turnovers, outsider appointments, and multiple successions.

The upshot? Although firing the CEO and hiring an outsider is the right call for a board of directors in some circumstances, it can be enormously costly to shareholders. Companies that have to fire their CEO forgo an average of $1.8 billion in shareholder value compared with companies that plan, regardless of whether the replacement is an insider or outsider. There is a far greater payoff to getting CEO succession right than current succession practices and investments would imply. The $112 billion price tag also raises the question of CEO succession to a core strategic issue.

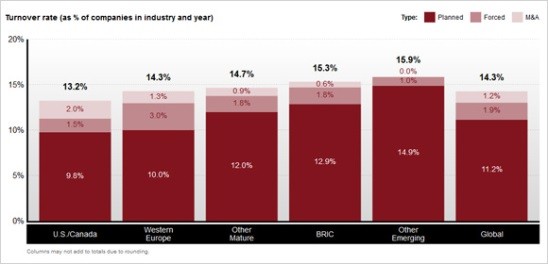

Fortunately, substantial progress has been made in recent years. Overall, boards of directors and senior executives have become significantly more practiced at planning smooth successions during the 15 years we have tracked CEO turnover. In the early 2000s, about half of all CEO successions were planned, and the percentage remained around that rate, with some variation, through most of the decade. But from 2009 onward, the percentage of planned successions has steadily increased, to a record 78 percent in 2014 (see Exhibit 2). Forced turnovers have become much less common. In 2000, 26 percent of departing CEOs were forced out, but in 2014, that figure was only 13 percent — a new low. (Each year, mergers and acquisitions account for a small minority of CEO changes; the figure was about 9 percent in 2014.) The data also shows that incoming CEOs include a growing number of women, and incoming chief executives are also increasingly better educated than in the past. We believe these trends reflect an overall improvement in corporate governance — but there is still plenty of room for growth. (See “The Incoming Class of 2014: No Surprises.”)

Getting Succession Right

Failed CEO successions are usually a result of boards having allowed succession planning to fall off their regular agenda. This happens a lot, because many boards treat succession as a discrete event, not as a process, leading them to overdelegate succession planning, usually assigning it to the CEO. Moreover, neither the board nor senior management typically pays enough attention to developing future generations of CEOs at all levels. We’ve also observed that boards tend to rely too much on the candidates’ track records, thus effectively making their choices based on what has worked in the past rather than on what will work in the future.

To avoid the penalty for getting the transition wrong, we recommend that companies undertake a review to test whether their succession practices are as good as they should be. This review should consist of four key questions.

1. Does your board really “own” the succession process? At many companies, the succession narrative largely revolves around the sitting CEO. When will the boss leave? And who is being groomed by the CEO as heir apparent? But this way of thinking ignores the requirements of corporate governance, in which the board is theoretically the paramount governing body. The board needs to have the responsibility — and the accountability — for choosing the next leader.

Although the incumbent CEO’s judgment will naturally be an important factor in the board’s decision making, simply delegating the choice of the next boss to the current one is a mistake. Why? Incumbent CEOs have an inherent conflict of interest in identifying and grooming potential successors. Most CEOs are not looking to be replaced, and the stronger the bench of potential successors, the more evident it may become to the board and the CEO that he or she is not irreplaceable. This conflict can also affect the CEO’s decisions about which of the company’s senior leaders should be identified as potential future CEOs, and should thus be given the kinds of assignments and responsibilities that will better prepare them for the top job. What’s best for the CEO may not always be best for the potential successors’ development.

One difficulty in effectively controlling the succession process is that simply raising the issue can create awkwardness or raise sensitivities. Indeed, circulating an agenda for a board meeting with a new item labeled “CEO Succession” might set off alarm bells throughout the company. For that reason, the board should find ways to make CEO succession planning a routine, recurring, and candid topic of discussion. Board practices vary, but one simple way to ensure that succession planning never falls off the table is to list it as a standing item on the board’s strategic agenda. The best approach is to include a CEO-free session during each board meeting, presided over by the lead outside director. This is one reason that separating the roles of CEO and chairman of the board is a basic rule of good governance.

It is common for boards to request that senior leaders who are potential successors present to the directors on their businesses and other routine matters. The idea is to give board directors regular, face-to-face interactions so they can get a firsthand understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of the company’s CEO bench. Unfortunately, this practice can easily devolve into a series of highly rehearsed dog-and-pony shows that never shine a true light on the senior leaders in action. As a better alternative, some boards have an “issues agenda” on top of their strategy process, in which they review specific threats or opportunities that may affect the company. Board members can request that the leading potential successors take charge of these issues and present on them. This has the great benefit of killing two birds with one stone: seeing the candidates in action while making progress on the issues and opportunities that are important to the company’s future.

2. Does your board really have a plan, and is it private? Life can be cruel and uncertain, even for the world’s top corporate leaders. A CEO can become debilitated by a stroke, or die in a plane crash, decide to run for office, or simply decide he or she would like to retire immediately. The board members should always have — in effect, if not in fact — a “secret envelope” summarizing the succession plan and the names of the senior leaders they believe are capable of leading the company at any given moment.

The board should take care to keep the names on the list private to minimize the risk of key leaders departing (should they learn they’re not on the list) and also of undercutting the authority of the incumbent CEO. In some successions, companies have telegraphed the coming change by elevating the heir apparent to the chief operating officer position. But this practice has become steadily less common. (See “The Decline of the COO,” by Gary L. Neilson.) In our view, this type of “on deck” promotion can be counterproductive, and the better practice is to make a clean break.

Keeping the succession plan private is difficult. Companies don’t keep secrets well. Shareholders and other stakeholders may feel they have a right to know, and the financial media is always looking for a good succession story. At Berkshire Hathaway, for example, media speculation surrounding which executive might succeed the now 84-year-old Warren Buffett has been raging for more than a decade. Some large companies have invited public attention by creating a “horse race” in which several senior leaders are told, in advance of a planned succession, that they are finalists, and invited to compete for the job. Although some exceptional leaders have emerged from this kind of process, it is disruptive and divisive, and likely to result in an exodus of talent. The interests of the company would be better served if the board acted decisively and minimized uncertainty about the future leadership.

Not having a plan makes it more likely that when a change is needed, the board will be forced to act precipitously. The result, all too often, is the choice of the wrong person, or the appointment of an interim CEO, which suggests indecisiveness and creates uncertainty. When Yahoo fired CEO Carol Bartz in the fall of 2011, it named then-CFO Tim Morse as interim CEO while engaging in a secretive search for a new chief executive. After four uncertain months, as the future prospects of internal candidates were left dangling, the board hired a new CEO from outside — former PayPal executive Scott Thompson. Thompson, in turn, was let go within weeks as activist investors questioned his academic credentials and his suitability for the job. In this instance, the failure to plan adequately led to apparent chaos. When a board of directors announces the departure of a CEO and the hiring of an executive search firm to identify a successor, the board members are also announcing that they have failed at succession planning.

3. Is your company truly proactive about developing future generations of CEOs? Perhaps the best way to avoid the disruption of having to bring in an outside leader is to do a better job at developing talent internally. Boards would be well served to treat CEO succession as a process that will be years in the making, not as a decision made over the course of a week or two. The board, the CEO, the chief human resources officer, and the senior leadership team need to work together to ensure that the company’s leadership development process is preparing successors for the CEO position, and that other executives are rising from further down on the management pyramid to fill other vacancies. The board is directly concerned with the names at the top: the two or three executives who are candidates for a succession in the short term, and the dozen or so senior leaders who are on track to become CEO two to three successions out. Responsibility for the career development of the next-tier leaders — 50 to 100 executives, at most large companies — rests with the CEO and the senior team.

General Electric, one of the most successful companies in U.S. business history, stands as an example of orderly succession planning through internal development. In its 117 years, GE has had fewer than a dozen top leaders. And it has had only two CEOs in the past 34 years. In 2001, when Jeff Immelt succeeded Jack Welch as chief executive officer, the change represented the final promotion for an executive who had joined the company 19 years earlier and had risen through the ranks. Immelt was replacing a CEO who had spent 21 years being gradually promoted at GE before being named to the post in 1981. GE’s continued effort to develop executive talent has qualified many top-tier alumni for chief executive positions at other companies — a fact that helps attract high achievers to GE.

Too often, development of the CEO talent pipeline becomes perfunctory — a box-checking exercise in which each manager lists who should take over if something happens, tagged on at the end of a performance appraisal. Instead, the process should be proactive, with care taken that the company is consistently developing people for bigger jobs. Leadership development models are frequently too concerned with vertical and functional roles, neglecting lateral moves, such as international assignments, that can round out future leaders’ experience. Our data shows that CEOs at the highest-performing companies more often have had international experience. Indeed, although only 33 percent of this year’s incoming CEO class members have international experience, it is reasonable to think that international posts may soon become a sine qua non for promotion to the corner office. Stephen Easterbrook, who was named CEO of McDonald’s in early 2015, joined the company in the U.K. in 1993 and held important executive posts in the U.K. and Europe before being named chief brand officer in 2013.

Identifying the best candidates can be difficult because there is frequently a bias within companies — a bias, in fact, in human nature — toward relying on familiar faces. The board should resist this tendency. Most boards have a grandfather principle whereby the CEO suggests senior appointments, but the board must approve them. The board can in such cases have a large influence on these appointments by asking the right questions and challenging the CEO about specific choices.

Oversight of the future-CEOs development program will also enable the board and the senior team to spot current or emerging weaknesses in the management lineup. The board may conclude that no senior leader is the right candidate to lead the company if a change becomes necessary, or that they have an insufficient number of candidates with development tracks that will eventually make them the right choice. In such cases, it is imperative to move early and proactively to fill the void before the need to make a change arises. This action enables the incoming leaders to get to know the company, show their abilities, and become potential CEOs over an appropriate time frame. The same practices should be used by the company leadership to fill emerging gaps in the second tier of managers.

4. Is your succession planning backward-looking or forward-looking? The board’s overall approach to choosing the CEO’s potential successors should start with what the company will need in the future and how that is different from what it has needed in the past. Instead, many companies start with executives’ track records.

Track records are always more tangible than the facts about executives’ capabilities, and boards of public companies understandably find it easier to promote people on the basis of tangible facts. But such facts are backward-looking. As a result, boards tend to choose candidates who have thrived under the business model the company has pursued in the past. These candidates may have been standouts in that context, but changes in the industry, in markets, or in technologies may suggest different competencies are required for success in the future. When Ford Motor Company was seeking a new CEO in 2006, it proved willing to look outside the traditionally insular auto industry and hired Alan Mulally, the former CEO of Boeing’s commercial airplanes division. During his eight-year run, Mulally steered Ford through difficult shoals and engineered an impressive turnaround. There were surely many highly competent executives within Ford who had superb track records of delivering results. But Ford’s board rightly judged that those executives did not necessarily have the skills the company needed for this crucial juncture.

Many companies today are facing significant threats to their established business models. Indeed, sooner or later, all companies do. Senior leaders in those companies will have excellent operating experience within those business models. But that may not be sufficient to guide their companies through the changes necessary to secure their future.

Even if it is discussed openly and frequently at the board level, the topic of succession will always raise some discomfort. And good succession planning requires meaningful investments of time and resources. But those investments are worth it — the cost of doing things poorly is in the billions. Moreover, the way companies manage CEO succession is a reflection of the way they manage their enterprise in general. Getting CEO succession right is one area where companies can control their own fate. ![]()

Succession Planning and Financial Performance

How do we know that good succession planning is good business? We reviewed the characteristics of successions over our 15-year data set, slotting all companies that had a succession event into quartiles ranked by their total return to shareholders over each departing CEO’s tenure — a total of 4,498 succession events.* We then used two indicators as proxies for poor succession planning: forced successions, wherein the board found it necessary to unseat an incumbent CEO; and the choice of an outsider as the new CEO. In the former case, as noted in the main story, forced turnovers suggest problems with succession planning. In the latter case, the need to hire an outsider suggests an inability to develop senior leaders with the right mix of talent and experience to run the company. Although there are instances in which hiring an outsider makes sense (for example, when an industry is undergoing disruption and new capabilities are required to compete), insiders delivered higher median total shareholder returns annualized over their entire tenure in 10 of the 15 years we have tracked.

We found that companies in the lowest performance quartile exhibited characteristics of poor succession practices at a greater rate than other companies. They forced out current CEOs more than twice as frequently as companies in the higher quartiles: Forced turnovers accounted for 45 percent of all successions at companies in the bottom quartile, compared with 21 percent for companies in the top quartile (see Exhibit A). Companies in the lowest quartile also appoint outsiders or interim CEOs to replace the outgoing CEO more often than other companies — in 40 percent of all successions, compared with 31 percent for the highest-performing companies over the 10-year period from 2005 through 2014. Companies in the lowest quartile also turn over their CEOs more quickly. CEOs in these companies have a median tenure of 3.4 years, compared with a median of 4.8 years for companies in the highest performance quartile. These characteristics suggest that companies in the bottom quartile are frequently surprised by the need to find a replacement and lack good internal CEO candidates.

By contrast, companies in the top performance quartiles showed signs of good succession practices. Top-performing companies had planned successions 79 percent of the time, and, coincidentally, hired 79 percent of their CEOs from inside. And in planned successions, they were able to replace one insider with another more frequently than were low-performing companies — an indication that high performers have more robust pipelines of senior executives prepared to fill the CEO position (see Exhibit B).

Interestingly, the best-performing companies share one succession characteristic with those in the bottom quartile — both of which are distinct from the companies in the middle quartiles. Like the low performers, companies in the top quartile tend to change CEOs somewhat more frequently than average performers. (Median tenure was 4.8 years compared with median tenure of just over six years for companies in the middle quartiles.) We hypothesize two possible explanations for this. First, it could be that CEOs of high-performing companies are poached more frequently by other companies. Second, the increased frequency with which top-quartile companies change CEOs may reflect a proactive drive for excellence, whereas in the lowest quartile, it suggests a reactive need for survival.

- * We measure total shareholder return (TSR) as TSR relative to the indexes on which companies trade, annualized for outgoing CEOs’ total tenure as CEO. The quartiles of performance were created by dividing all companies having a turnover in a given year into four groups.

The Incoming Class of 2014: No Surprises

The ways the 330 executives who became CEO in 2014 ascended to their job show continued improvement in corporate governance at the world’s 2,500 largest companies. Forced turnovers, which are generally indicative of poor succession practices, are becoming less and less common. And the fact that 17 members of the Class of 2014 (about 5 percent) were women continues the trend toward greater diversity — albeit from a very low level — that we noted in last year’s study. The demographics of the incoming class indicate that companies continue to hire CEOs who are otherwise familiar to them: Most are from the country where their company is headquartered (85 percent), most have worked in only one region (67 percent), and most joined their company from another in the same industry (57 percent).

Overall, the percentage of incoming CEOs appointed in a planned succession rose to a record high of 78 percent in 2014, up noticeably from 71 percent in 2013, and up markedly from 44 percent in 2006. The percentage of incoming CEOs who were promoted from inside the company was also 78 percent, up from a recent low of 71 percent in 2012. At the 78 companies with planned successions that followed the “apprenticeship model,” whereby the outgoing CEO becomes board chairman to mentor the new CEO, the share of incoming CEOs who were insiders was particularly high: 92 percent.

As we have noted (see “Succession Planning and Financial Performance”), these trends point to improving CEO succession practices and should presage better financial results.

Another sign of progress: The percentage of incoming CEOs who also hold the chairman of the board position, which we consider to be a poor corporate governance practice, was near its all-time low in 2014, at 10 percent. This continues a major shift in corporate governance since the early 2000s, when the number of joint CEO–chairman appointments each year ranged from 25 to 50 percent. Companies that forced out their CEO awarded joint titles to the incoming CEO 14 percent of the time over the last decade, compared with 10 percent for companies with planned successions.

As noted above, women made up 5 percent of the 2014 incoming class, up from 3 percent in 2013. This continues a trend we observed in last year’s study of slow but consistent growth in the share of women CEOs (see Exhibit C). Our data continues to show that women CEOs can expect to face stiffer headwinds than their male colleagues: Women CEOs were more often outsiders (33 percent over the 11 years from 2004 to 2014, compared with 22 percent for men), and were more likely to be forced out (32 percent versus 25 percent for men).

Regions, Industries, and Education

Although the share of CEOs coming from the same country as their company headquarters in 2014 remained near its 82 percent average of the last five years, there were significant variations by region. Western European companies most commonly appointed CEOs from other countries over the last five years, making up nearly a third of all cases. Japan and China did so least often, appointing foreigners only 2 percent and 1 percent of the time, respectively. Western European countries also had the highest share, at 53 percent, of incoming CEOs in 2014 with experience working in another region, compared with 24 percent in the U.S. and Canada, and none in China (see Exhibit D).

The proportion of incoming CEOs who joined their company from another in the same industry — 57 percent — has been about the same for the last three years, but varies greatly among industries. Energy and financials stayed closest to home in 2014, with 89 percent and 84 percent of CEOs, respectively, coming from their own industries. Utilities companies, which face deregulation and are in need of new capabilities, looked furthest afield, with only 17 percent of new CEOs joining the company from within the utilities industry (see Exhibit E). Overall, just 20 percent of incoming CEOs in 2014 had worked in only one company throughout their careers.

New CEOs are also becoming more educated. The number of incoming CEOs who hold an MBA reached a new high of 34 percent in 2014, a 75 percent increase from the rate 11 years ago. Additionally, 10.5 percent of incoming CEOs in 2014 held Ph.D. degrees. And they’re getting a bit younger. The median age for incoming CEOs in 2014 was 52, one year younger than that of those appointed in the previous two years.

Methodology

Strategy&’s 2014 Chief Executive Study identified the world’s 2,500 largest public companies, defined by their market capitalization (from Bloomberg) on January 1, 2014. We then identified the companies among the top 2,500 that had experienced a chief executive succession event between January 1, 2014, and December 31, 2014, and cross-checked data using a wide variety of printed and electronic sources in many languages. For a listing of companies that had been acquired or merged in 2014, we also used Bloomberg.

Each company that appeared to have changed its CEO was investigated for confirmation that a change occurred in 2014, and additional details — title, tenure, gender, chairmanship, nationality, professional experience, and so on — were sought on both the outgoing and incoming chief executives (as well as on any interim chief executives).

Company-provided information was acceptable for most data elements except the reason for the succession. Outside press reports and other independent sources were used to confirm the reason for an executive’s departure. Finally, Strategy& consultants worldwide separately validated each succession event as part of the effort to learn the reason for specific CEO changes in their region.

To distinguish between mature and emerging economies, Strategy& followed the United Nations Development Programme 2013 ranking.

Total shareholder return data for a CEO’s tenure was sourced from Bloomberg and includes reinvestment of dividends (if any). Total shareholder return data was then regionally market-adjusted (measured as the difference between the company’s return and the return of the main regional index over the same time period) and annualized.

Reprint No. 00327

Author profiles:

- Ken Favaro is a senior partner with Strategy& based in New York. He leads the firm’s work in enterprise strategy and finance.

- Per-Ola Karlsson is a senior partner with Strategy& based in Dubai. He serves clients across Europe and the Middle East on issues related to organization, change, and leadership.

- Gary L. Neilson is a senior partner with Strategy& based in Chicago. He focuses on operating models and organizational transformation.

- Also contributing to this article were s+b contributing editor Rob Norton and, at Strategy&, senior manager Josselyn Simpson, associate Veronica Pirola, and senior analyst Spencer Herbst.