Best Business Books 2005: Leadership

Monsters and Diplomats

(originally published by Booz & Company)Leadership books keep rolling off the presses as if their authors had something new to say. Amazon.com currently lists some 16,175 leadership titles. That figure can’t be right: A significant new theory of leadership hasn’t been advanced in years, and there are few serious research findings to report. Yet authors keep churning out books.

Things haven’t always been so. In fact, not until the 1980s was there an identifiable leadership niche in the business book industry. Since then, as the genre has grown exponentially with every passing year, authors have had to stretch further for themes and subjects. And every year your faithful correspondent for strategy+business’s annual “Best Business Books” issue has had to look further afield for interesting books to review. This year’s crop takes us as far away as South Africa in the 19th century, with stops in contemporary Washington, D.C., New York City, and 1970s New Orleans.

Drilling into Clay

The common denominator of Michael Lewis’s popular business-related books is the author’s remarkable facility to make his real-life characters appear ridiculous. Hence, I approached Mr. Lewis’s latest effort, Coach: Lessons on the Game of Life (W.W. Norton, 2005), with expectations of a healthy dose of his patented cynicism. Instead, I found a small serving of treacle.

Small is an understatement: This tiny book is only 90 pages; 25 are given over to photographs, of which only two are directly related to the text. Needless to say, the book is a fast read! But the most remarkable thing isn’t the publisher’s chutzpah in charging nearly 13 bucks for a padded work that isn’t long enough to qualify as a feature article in the New Yorker. What truly amazes is that the author of the techie New New Thing: A Silicon Valley Story (Norton, 2000) could have written a book with such old messages.

The coach in question is one Billy Fitzgerald, Mr. Lewis’s baseball coach at the private high school in New Orleans he attended some 35 years ago. Still on the job, Coach Fitz is a walking stereotype of a kind seldom found today: the tough Marine drill sergeant with a heart of gold. Old Coach Fitz loves his team to death, hollering at them, belittling them, throwing furniture, making them practice sliding into third base on a surface so hard it leaves them bloody and bruised — all in the name of “making them men.” This coach is an old-fashioned character builder: He is out to instill discipline in the unformed clay of youth.

When the young Mr. Lewis is on the pitcher’s mound attempting to get a batter out, Coach Fitz taunts him from the dugout about his recent “sissy” skiing vacation. Mr. Lewis reports that the razzing causes him to lose concentration, and, subsequently, he takes a sharply hit ball on the nose, breaking his beak in five places: “Grim as it sounds, I don’t believe I had ever been happier in my adolescent life.” Why? “Immediately, I had a new taste for staying after baseball practice, for extra work. I became, in truth, something of a zealot, and it didn’t take long to figure out how much better my life could be if I applied this new zeal acquired on a baseball field to the rest of it.” Mr. Lewis implies that if Coach Fitz hadn’t terrified the crap out of him, he might still, in his 40s, be behaving like a feckless teenager.

Coach Fitz’s message, the author reminds us, isn’t about baseball or even about winning. “He was teaching us something far more important: how to cope with the two greatest enemies of a well-lived life, fear and failure.” It doesn’t occur to Mr. Lewis that it is far from self-evident that those are, in fact, the two greatest enemies of a well-lived life (what about arrogance, dishonesty, cruelty, the inability to love?). Nor does he seem aware that there are other ways of “getting [discipline] into adolescent heads” besides hurling furniture. He doesn’t consider the possibility that a young man raised on verbal abuse might one day end up being an abusive leader himself (or, say, an author whose modus operandi is to mock people). I could go on, but my commentary is getting longer than the book.

Lessons from Zululand

Lessons from Zululand

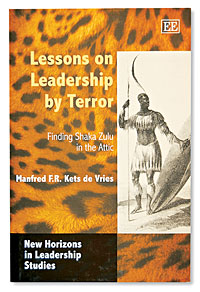

Coach Fitz turns out to be a piker compared to Shaka Zulu, the subject of Manfred F.R. Kets de Vries’s Lessons on Leadership by Terror: Finding Shaka Zulu in the Attic (Edward Elgar, 2004), a psycho-historical analysis of one of the world’s cruelest despots. Between 1816 and 1827, Shaka united hundreds of loosely related clans spread over 1 million square miles in Southeast Africa into a centralized kingdom of more than 500,000 people, all subservient to his whim. He created the Sparta of Africa, a mighty nation with a standing army that may have numbered 100,000 fierce warriors armed with a weapon of mass destruction, the assegai, a spear with an 18-inch blade. It was a mistake to resist Shaka’s forces: After they had slain all the men in an opposing village, for good measure his warriors would impale the women and children on stakes.

Shaka was a bit paranoid. On the basis of how people looked at him (or how they smelled), he killed thousands of his loyal subjects: “He routinely made life-and-death decisions while taking his morning bath.” According to a contemporary report, when one of Shaka’s favorite wives presented him with a son, “The monster took the child by the feet, and with one blow dashed his brains out upon the stones; the mother, at the same moment, was thrust through with an assegai.” The guy was a holy terror.

Dr. Kets de Vries, a clinical professor of leadership development at INSEAD in Fontainebleau, France, who holds a doctorate in management and is a psychiatrist, places Shaka on the couch, analyzing his “inner theatre” from a safe distance of some 200 years, across cultures, and without a single direct quote or written word from the analysand himself. It turns out Shaka had an absent father, an overbearing mother, and a childhood filled with humiliation. Well, no wonder! Hence, Dr. Kets de Vries’s diagnosis: Shaka had an advanced case of “psychopathology Rex,” characterized by “reactive narcissism” (the worst kind), megalomania, a Monte Cristo complex (insatiable desire for revenge), egotism, and “deep-seated feelings of inferiority.”

One might wonder why an executive should care about all this. But here’s where it gets interesting: Dr. Kets de Vries tells us that “studies of human behavior indicate that the disposition to violence exists in all of us; everyone has a Shaka Zulu in the attic.” If so, you won’t catch me going up there. The author says his purpose in telling the tale of Shaka is not to give readers historical enlightenment but, instead, to help them learn more “about people who engage in ruthlessly abrasive behavior in the workplace.” To that end, he describes his INSEAD leadership seminar designed “to make the senior executives who participate aware of how their behavior and actions affect others.” In the book, he attempts to draw business “lessons in leadership” on the basis of Shaka’s nasty behavior. Unfortunately, the links he draws between Shaka’s behavior and those lessons (“Promote Entrepreneurship,” “Set a Good Example”) are tenuous at best. For that we should give thanks. After all, there are few murderous despots in corporate leadership today. The problem, in fact, is that there are too many petty tyrants in the mold of Coach Fitz. But Dr. Kets de Vries doesn’t bother with such small potatoes.

Although you won’t learn much about business leadership reading this book, you will definitely pick up some neat anthropological tidbits to share over cocktails: Did you know that every Zulu king once was served by “a royal anus-wiper, whose duty it was to hide the royal stool so that evildoers could not take possession of it”? Now, that’s an executive perk worth writing home about.

The Anti-Shaka

Dennis W. Bakke, cofounder of the energy giant AES Corporation and CEO from 1994 to 2002, has written the most fascinating, if not the downright strangest, leadership book I’ve ever read: Joy at Work: A Revolutionary Approach to Fun on the Job (PVG, 2005). It is a good thing that CEOs are grossly overpaid. Otherwise Mr. Bakke might not have been able to afford to put out this self-published book. Vanity presses were never like this, with full-page ads in national publications, free books for b-school profs, an accompanying audiobook and related DVDs, and a heavily promoted national book tour. All told, he must have spent a bloody mint on the project. But why?

The book’s first 204 pages are, if not a joy, an impressively well-formulated compendium of just about the sanest and sagest managerial advice you will find sandwiched between covers. He echoes — sometimes unconsciously repeats — insights from the most thoughtful books written by people-oriented CEOs: Imagine the best of Bob Townsend, Max DePree, Jan Carlzon, and Jack Stack, along with a judicious admixture of guru-grounded wisdom à la Douglas McGregor, Abraham Maslow, Tom Peters, and Bob Waterman (the latter served on AES’s board). When it comes to treating people right, what Mr. Bakke says and does is textbook perfect. He is the anti-Shaka.

Importantly, to Mr. Bakke, creating joy at work doesn’t mean providing workers with beer and skittles. Instead, it “gives people the freedom to use their talents and skills for the benefit of society, without being crushed or controlled by autocratic supervisors or staff offices.” To accomplish that at AES, he tossed out organization charts, job descriptions, and the HR department, and gave every worker the authority and opportunity to learn, grow, and make a difference to the company’s performance. He put nearly all of AES’s 35,000 workers on a salary, organized them into self-managing teams of 15 to 20 members, gave them access to “insider” financial data, and left them free to find ways to improve the organization’s effectiveness. He then carefully measured their performance, held them accountable, and rewarded them on the basis of their contribution. In doing so, he took direct aim at the country’s corporate Coach Fitzes, making a convincing case that if you treat people like adults, they will act like adults.

Alas, reading the book is not an unalloyed pleasure. We get much too much about the author’s wonderful parents, brilliant wife, and beautiful children. He offers too many cloying little stories and homilies. He is a first-class name-dropper (and may have set a record for the largest number of celebrity blurbs). There is excessive self-congratulation, overuse of the first-person personal pronoun, and a smug sense of certainty. He wears his religious virtue on his sleeve, and goes on and on about everything he believes, work related or not. All of this seems unnecessary. Why ruin a great story with overkill?

Then, in chapter nine, we find the solution to the mystery of why Mr. Bakke has written this book in this way, and promoted it so aggressively with his own money. Here we learn that AES’s share price, which hit its high of $70 in 2000, fell below $5 less than two years later. Apparently the board lost confidence in him shortly thereafter and — well, you know how these things go — he “resigned” as CEO. It now becomes clear that the book is Mr. Bakke’s apologia, his justification of his actions. There is no joy in this chapter. Indeed, here we see another side of the author, defensive and scrambling to explain himself. It is all very complicated, and clearly there are at least two credible sides to the story.

The chapter is dramatic, informative, and, ultimately, sad — because the reader knows, as Mr. Bakke himself must know, that no matter how many good things he did, his record will always be tarnished by the financial mess that ended his watch. Without doubt, he was an impressive manager of people, one of the best in America during the 1990s, when few leaders cared to demonstrate ethical concern for their employees. But he also was an unfortunate — perhaps incompetent — strategist, and even being the greatest people manager won’t compensate for that when the bills come due.

The Old-Fashioned Way

John C. Whitehead’s A Life in Leadership: From D-Day to Ground Zero: An Autobiography (Basic Books, 2005) is the memoir of the chairman of the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, the agency charged with resurrecting the devastated 16 acres where the World Trade Center once stood. Even at age 80, Mr. Whitehead appears to have the right credentials for that tough political job: navy service at Omaha Beach, success as co-CEO of Goldman Sachs, experience as No. 2 in the State Department during Ronald Reagan’s face-off with the Soviet Union, and membership on the board of just about every civic and philanthropic organization that counts in the Social Register. The guy has a resume, and a Rolodex, to die for.

What he doesn’t have is a track record of visionary leadership, if the ability to enlist reluctant followers in fundamental change is the hallmark of such. Instead of using fanfare or bravery, Mr. Whitehead succeeded the old-fashioned way: diplomatically. As he reports it, everything he has said and done over his entire career is politic, courteous, and nonoffensive. He is a patient, kind, and thoughtful listener, even when being berated by a first-rate Wall Street egotist, a second-rate Marxist despot, or a third-rate American politician.

His reminiscences are discreet: If he kissed, he doesn’t tell. But just when you are becoming exasperated, wishing he would say something shocking or report that he once did something dramatic, you suddenly realize you both like and respect the author for who he is. In fact, he is one of the last of that breed of moderate Republicans — folks with solid Midwest values, Ivy League educations, and a sense of responsibility to the big cities where they worked — who ran our largest corporations from the end of World War II through the Ford administration. The likes of John Whitehead worked diligently to keep the country they loved on an even keel, offering workers secure jobs with good benefits, giving generously to charitable causes, and serving in positions of civic and public leadership. Without boasting, he describes this brand of “quiet leadership” in the last, and best, chapter of the book. I commend this book, especially to young, aspiring leaders, if only to remind them that in this country there once was a brand of leadership that was thoughtful rather than brash, persuasive rather than belligerent, encompassing rather than divisive, and idealistic rather than ideological.

Authors being authors, and publishers being publishers, we can expect yet another round of scribbling about leadership next year, whether or not there is anything new or useful to say on the topic. As a repeat offender myself in this regard, I’m the last one to be critical of my fellow authors. Instead, the responsible thing for me to do here in conclusion is to give them some guidance by identifying the next important leadership subject deserving of a new book. But, then, if I knew that, I’d write it myself.![]()

James O’Toole (jim@jamesotoole.com) is research professor at the Center for Effective Organizations at the University of Southern California. His research and writings have been in the areas of philosophy, corporate culture, and leadership. He has written 14 books; the latest is Creating the Good Life: Applying Aristotle’s Wisdom to Find Meaning and Happiness (Rodale Press, 2005).