The Dance of Power

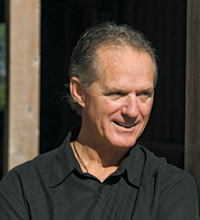

Richard Strozzi-Heckler teaches military and business decision makers how to build the muscle and fluency of leadership.

(originally published by Booz & Company)Is leadership an art or a science? The question has long been subject to debate. Which side you’re on probably determines whether or not you believe leadership can be taught. But for developing leaders who can respond to the challenges of today’s 24/7 business environment, perhaps the art-versus-science dichotomy is too theoretical to be of use.

|

|

Photographs by Tom Tracy |

Richard Strozzi-Heckler has built a distinctive and influential career based on the proposition that leadership is neither art nor science, but rather a practice that can be developed and trained for. Just as a pianist must run through scales in preparation for a concert and a ballplayer must spend time in the batting cage before a game, so in Strozzi-Heckler’s view can a leader methodically build fluency and muscle through the regular exercise of disciplines that require simultaneous physical and mental effort.

“Human beings change through practice,” he says. “You can be very smart, but if you just talk about something, you never learn to do it. And practice requires being systematic, performing a sequence of movements over and over until it becomes part of your physical being, part of who you are.”

This emphasis on practice in the service of continual refinement connects Strozzi-Heckler with the most effective organizational ideas of the last half century: W. Edwards Deming’s method of building quality in a given process, Peter Senge’s work on systems thinking, and the continuous improvement loops (known as kaizen) that characterize the Toyota production system — the precise recalibrations that have transformed the management of supply chains. All these innovations emphasize the process of becoming, rather than the achievement of a final state. So it’s not surprising that they all draw upon Eastern culture.

Strozzi (the Heckler part of his name, which came from a stepfather, never really stuck) adds a refinement to this tradition by translating its intellectual underpinnings into a form that can be physically embodied. Just as Frederick Taylor mapped the precise physical movements that maximized productivity in the industrial era, so Strozzi provides a means for maximizing the opportunities inherent in our knowledge era by showing how wisdom can be made manifest through human movement.

Drawing on a lifetime spent studying martial arts and Eastern philosophy; decades of training in competitive sports; and stints as a marine, soldier, volunteer firefighter, psychologist, and professor, Strozzi has created an eclectic but disciplined and replicable program for helping leaders develop the physical presence, fine-tuned awareness, bias for action, and precise articulation of purpose that inspire confidence and trust among those who work with them.

Over the last 25 years, he has delivered his programs to an extraordinary range of clients: not only to executives at companies such as Pfizer, Motorola, Cargill, Microsoft, Hewlett-Packard, Cemex, and Capitol One, but to senior military leaders, U.S. Marines, Navy SEALs, and counterinsurgency agents operating behind the front lines. He has also worked with law enforcement officials, urban gang members, prisoners, Olympic athletes, and professional sports teams. The level of conditioning among these highly varied participants runs the gamut from channel surfer to triathlete. Yet in Strozzi’s classes they come together in a choreography of complex movement that is physically challenging but unconnected to the Western understanding of athletics.

In the mainstream Western tradition going back to the Greeks, the physical component of leadership has been identified with athletic prowess. Athletics have been viewed as a vehicle for building “character” (the Outward Bound course that requires battling the wilderness), instilling self-discipline (the batting cage), or imparting the habits of command that come from captaining a team. Given this close association, organizations have often assumed that athletic excellence automatically translates into skilled leadership. Think of how many companies are quick to tell you that the CEO quarterbacked for a championship team in college, or that the managing partner has been invited to play the Pro-Am at Pebble Beach.

But the equation between sports and leadership, and the metaphors it has inspired (“he fumbled that one,” “let’s aim for the bleachers”), seem outdated and culture-specific in today’s highly diverse global organizations. Changing demographics and technologies have made competitive sports less relevant and inspired a backlash that finds one expression in the exaltation of the nerd.

This leaves leadership with something of a mind–body problem, for without the focus on sports, how can leadership be “embodied”? It’s an important question, because manifesting a leadership presence is essential, as anyone who has attempted to exert influence over a dog, a horse, or even a young child using only the force of rational intelligence can attest. A solely intellectual approach leaves something fundamental out of the leadership equation, negating that aspect of human nature rooted in the animal world that was probably programmed into our limbic brain early in our species’ development.

Strozzi has tried to address the gap by developing an insistently physical yet nonathletic program of leadership training suited to an era in which the definition of “what a leader looks like” is rapidly evolving. His methods are also appropriate for organizational cultures in which networks and teams are replacing hierarchies. In top-down organizations, leaders can exert power by virtue of position, but in decentralized networks, people won’t follow unless they buy into what is being proposed. Hence the popular emphasis on “walking the talk,” another way of saying that a leader’s principles must be embodied.

Lieutenant Colonel Fred Krawchuk, operations commander for the U.S. Army in the Pacific, was drawn to Strozzi’s work “because of how Richard integrates the physical and the intellectual.” In the military, as in business, says Krawchuk, “We place way too much value on being action-oriented. We think leaders are the guys who say, ‘Let’s just get it done.’ But that shortchanges thoughtfulness and reflection. How do we bring these qualities together? We develop awareness. If we can be fully present with other people and grounded in ourselves, we can integrate observation with our capacity to act.”

Nancy Hutson, who recently retired from Pfizer, where she was senior vice president for global R&D, sounds a similar note: “Richard works with body, language, and mood to help us be more aware of ourselves and more attuned to others. This gives us a foundation for building trust rather than just assuming it, which is what most people in hierarchies are used to doing. Richard’s emphasis on practicing leadership rather than being a leader also subverts the hierarchy, since being a leader is all about position.”

That Strozzi offers a way out of the mind–body dilemma seems fitting, given that he has struggled with his own version of the problem all his life. Like most teachers who develop a distinctive corpus of work outside the framework of institutions, Strozzi has made his teachings reflect what he has learned during his personal quest. In his case, that quest draws paradoxically from both the 1960s counterculture and the military, from academia and the worlds of sports and martial arts. By inclination, temperament, background, and experience, he has been well positioned to bridge cerebral and visceral ways of being in the world. His chosen instrument of reconciliation has been aikido.

A quietly intense and strikingly handsome 63-year-old, Strozzi travels the world to deliver internal leadership programs for corporate and military clients. But now the world also comes to him. He teaches a menu of courses at the aikido practice center, or dojo, that he has built at the Strozzi Institute on an idyllic ranch in the green northern California hills between Petaluma and Bodega Bay. The setting is what most people envision when they daydream about chucking the corporate life and heading for a place of pastoral perfection where they can follow their passion to the utmost while somehow managing to earn a living.

Hippies and Soldiers

Strozzi’s method for adapting aikido as a tool for leadership training was not developed in the serenity of rural California, but in the sweaty and harsh environment of a military base. It started in the spring of 1985, when Strozzi was a practicing psychologist and aikido teacher in Mill Valley. His partner in the Tamalpais Aikido Dojo was George Leonard, a well-known figure in the West Coast human potential movement and author of the books The Ultimate Athlete, Mastery, and The Way of Aikido.

Leonard had been approached by Chris Mejer, the owner of the Seattle-based training company SportsMind, which had developed a physical conditioning course for basic trainees in the army. A group of senior officers had invited Mejer to create a classified pilot program that would deliver six months of full-time training in martial arts, meditation, biofeedback, guided relaxation, and mind–body psychology to two Special Forces A-teams –– Green Berets –– stationed at Fort Devon, Mass. The pilot was code-named the Trojan Warrior Project.

At Leonard’s suggestion, Richard Strozzi was asked to teach daily aikido classes to the participants and to help with the design and delivery of the entire program. He would also lead an unprecedented monthlong silent meditation retreat for soldiers at a remote former Boy Scout camp in rural New Hampshire.

The army’s rather startling goal for the project was to explore an approach to military training that would draw in part from cutting-edge “human technologies” seeking to integrate mind, body, and spirit, and in part from ancient warrior traditions from different cultures. The idea was to take what the base commander described as a holistic approach to enhancing the fitness, alertness, capacity to withstand stress, team cohesion, and potential for in-the-moment thinking among elite frontline units. The senior officers who commissioned the program also hoped that these Special Forces teams might, like the Greek warriors secreted in the belly of that famous wooden horse, prove a transformative force within the huge and highly bureaucratic belly of the U.S. armed services, serving as a template for developing the kinds of skills that would be required in 21st-century warfare.

Military training in the West has traditionally emphasized a strict chain-of-command structure that vests strategic decision making in those at the top and tactical implementation in those on the front lines. But by the mid-1980s, this hierarchical model was breaking down. The development of smart technologies — tanks, scopes, reconnaissance tools, and weaponry — was putting real-time information into the hands of frontline troops, requiring soldiers to make immediate decisions instead of awaiting instructions from headquarters. This change was eroding both the chain of command and the divide between planning and execution. To adapt, the military needed to train soldiers at every level to become more thoughtful, resourceful, and intuitive. According to Colonel Herbert Harback, former leadership instructor at the U.S. Army War College, “Advanced training used to be reserved for generals and colonels. That no longer works. Technology is forcing soldiers to make major real-time decisions. Training them to do so will transform the entire military.”

The army was also exploring new approaches to training as a result of the failures of Vietnam, where small-unit maneuvers, simplicity, and commitment had trumped the U.S. military’s vastly superior firepower. Strategists in every service branch had begun to recognize that unconventional challenges and threats would be their chief concern in the years ahead. Fighting guerrilla actions and insurgent networks while winning the hearts and minds of locals would require soldiers who were flexible and sensitive and who could inspire trust — qualities often at odds with military doctrines based on the application of overwhelming force. Nowhere was this paradox more pressing than in the Special Forces, who were first on the front lines but whose training fetishized the exercise of brute power.

Where to turn?

The unlikely answer proved to be the kind of Eastern disciplines that had gained a following during the 1960s and ’70s in American counterculture. Two organizations that Strozzi helped launch, Tamalpais Aikido and the Lomi School, were among the most prominent centers of the time. Most human potential–oriented institutions considered themselves (and were considered) the antithesis of military culture, hippies and soldiers standing on opposite sides of an antagonistic gulf. But the changing nature of warfare, as well as the desire of counterculture gurus like George Leonard to reexamine the role of the warrior in human culture, had by 1985 begun to bring these worlds into halting contact. The Trojan Warrior Project was the first programmatic attempt at integration.

Action and Philosophy

Action and Philosophy

When Strozzi received the call to go to Fort Devon, he saw the Trojan Warrior Project as an opportunity to extend the influence of disciplines he revered into a highly influential arena, and as a means of healing a sense of dividedness that had shadowed him throughout his life. The son of a career naval seaman, he had grown up on a series of military bases, studying judo in tin-roofed Quonset huts with enlisted instructors who emphasized the martial in martial arts. He went to Vietnam as a marine in the early 1960s, then bummed around Asia studying yoga and meditation, landing on the cover of Life magazine as an exemplar of the new global expatriate culture in 1968. After living in Hawaii and discovering aikido, he moved to San Francisco to apprentice in a catalog of alternative disciplines, including Reichian work, rolfing, Feldenkrais, polarity therapy, and a full slate of martial arts.

Having spent his younger years in open rebellion against the rigid discipline of his father, from whom he remained estranged, he saw working with Green Berets as a means of reconciling with the warrior culture he had been raised to honor but from which he had parted ways. “I understood that I needed to complete unfinished business from the past in order to be more fully alive in my present life,” he says. He also saw the program as offering a chance to heal the split between the intellectual and physical worlds he had inhabited, a tension that had plagued him since he won an athletic scholarship and became the first in his family to go to college.

He says, “I’d been a jock since I was a little kid, and I loved the physical charge, the challenge, the practices, and the bonding. But in the locker room, there was always this prohibition against saying anything important unless it had to do with the game. That limited the camaraderie, made it dull and shallow.” Majoring in English and philosophy at San Diego State University and later studying for his doctorate in psychology at the Saybrook Institute in San Francisco, he discovered that he thrived on intellectual discussion.

“It was incredible to sit around the coffee shop until all hours talking about big ideas,” he recalls. “But though the talk was great, it never seemed to go anywhere. Plus, I noticed that the people who had the most interesting conversations often seemed disconnected from their bodies, almost as if they weren’t physical beings at all. The two halves of my life, the physical and intellectual, were totally separate, which felt sterile. I wanted to combine them, find a way to cultivate philosophical depth while living in the world of action.” His immersion in aikido, a highly physical discipline based on Taoist principles of nonresistance and effortless effort, was a way of resolving this split. The idea of bringing it to the Special Forces was irresistible.

He took a six-month leave from his counseling practice, found a substitute to teach at his school, and made arrangements for his children, whose custody he shared with his ex-wife. The reaction from his Bay Area community was swift and outraged. A close friend excoriated him for “teaching meditation to a bunch of trained killers.” A choleric colleague publicly berated him for “taking money from the enemy.” A professor at a dinner party shouted at him that peace would never exist until the military was abolished.

Arriving at Fort Devon in the sweltering heat of August, he encountered a corresponding measure of antagonism from soldiers more accustomed to chewing tobacco and pumping iron than meditating or bowing reverently to opponents. Students protested that a practice rooted in Buddhism was anti-Christ. He was called everything from a heretic to “a San Francisco psycho-queer.”

But one look at the soldiers convinced him that they needed what the program had to offer. Superbly conditioned and physically strong, the Green Berets were also extremely rigid, their power concentrated in their upper torsos, their center of gravity so high (“typical in American males”) that it threw them out of balance. With chests thrust out, eyes narrowed, and jaws clenched, they had armored bodies, on guard and ready for attack.

But direct attack, like the soldiers’ unbalanced bearing, was useless in aikido, where intuition and grace put conventional strength at a disadvantage. Aikido emphasizes balance and contradiction. The practitioner displays strength in yielding, exerts force through nonassertion, unleashes power by blending and harmonizing with an attacker. Morihei Ueshiba, who developed aikido in Japan in the 1940s by combining jujitsu hand-to-hand techniques with traditional sword and stick fighting, taught that dominating others and winning at all costs had become obsolete with the advent of weapons of mass destruction.

Martial training, in Ueshiba’s view, must teach practitioners to disarm aggression rather than provoke it, to move with an opponent rather than charging at him. The master envisioned a world in which warriors offered loving protection to the community instead of seeking combat. Aware of this tradition, Strozzi saw aikido as the key discipline for developing warriors who could meet the demands of 21st-century warfare. Countering unconventional threats and undermining insurgencies would require that soldiers win the confidence of local populations and neutralize soft power. This, in turn, would require focused awareness, the ability to blend and harmonize with opposing forces. Strozzi says, “Our challenge was to get them to focus their attention internally, toward what they felt, sensed, and imagined. For men trained to perform feats of bravado and succeed through the sheer force of will, it was like asking the Hulk to take up knitting.”

The Green Berets were skeptical as they filed into the dojo Strozzi had constructed for them in an abandoned recreation center at Fort Devon. When he tried to talk about the philosophy of aikido, he was taunted. Let me have a baseball bat, and I’ll show you an American martial art. Hand me my .44 Magnum, and then try your technique. He knew that winning the men’s confidence would require sureness and skill. As he noted in the book he wrote about the experience, In Search of the Warrior Spirit, “Being inauthentic was a cardinal transgression in the eyes of these men. It unleashed the predator within them.”

In other words, he had to walk his talk so he could be credible, and he had to do it fast. In his book he describes arranging for another instructor to charge him from the back of the room full force with a bayonet fixed to an M-16 automatic weapon. As the man came screaming toward him, Strozzi stepped forward to blend with his attacker’s movements. Sensing an opening, he turned the knife out of his attacker’s hand and guided his body onto the mat, pinning him in a secure hold that looked effortless.

In the silence that followed, he invited anyone who wished to repeat the experiment. Several students felt compelled to try. “They were frustrated,” says Strozzi. “I was smaller and much older than they were. And I had nowhere near their level of physical conditioning. But aikido is not about being strong, it’s about being balanced and aware. You can’t force things. You have to feel the flow, then choose your moment.”

The six-month program proved arduous, demanding, intense, and at times frightening. Many soldiers resented every new practice that was introduced. During the silent meditation retreat, resistance flamed into rebellion: Wasn’t blending really about submission? Didn’t harmonizing contradict the rest of their training? And why on earth were they not supposed to smoke? But as the months passed, the entire staff noticed that the men were becoming more flexible, more responsive, better able to express emotions other than sarcasm or fury. The emphasis on being centered made them recognize when they were off center. This helped them identify what triggered their aggression, which in turn made them more self-aware. In Strozzi’s formulation, “Control follows awareness.” Control made the men more relaxed. “Instead of relying on armed musculature, they were able to develop an authoritative presence.”

When the Trojan Warrior Project was completed, a battery of tests showed off-the-charts progress. Participants improved by between 50 and 150 percent in their ability to control pain and body temperature, their ability to remain alert and motionless for significant periods, and their ability to recuperate from injury and stress. They also made dramatic gains in flexibility, physical endurance, coordination, and team cohesion.

Over the next few years, Strozzi would develop similar programs for Navy SEALs, Air Force rescue jumpers, and counterinsurgency operatives in hot spots like Afghanistan. In 1994, Major General Jim Jones, commandant of the U.S. Marines and former supreme allied commander of NATO, along with Assistant Commandant General Richard Hearney, asked Strozzi to create a corps-wide aikido-based program that would become part of basic training for every marine. Hearney was concerned about the values held by younger marines who had been raised in single-parent homes. He felt as if the technical training they received was not enough and was concerned about helping the marines adapt to a changing geopolitical environment. Having been exposed to tae kwon do while a platoon commander in Korea, Jones believed that the discipline, fierceness, and motivation that the practice instilled in the South Korean troops gave them advantages that the young marines would need to face a world of change. In 1986, as a batallion commander at Camp Pendleton, he began teaching martial arts to recruits; as a result, alcohol and drug abuse, along with domestic violence, unauthorized absences, and brawling, decreased. Morale soared.

The Fort Devon pilot also resulted in a significant increase in the participants’ leadership ability, as evidenced by one unit’s performance in leading the action in the 1993 battle of Mogadishu in Somalia. “That was not an original goal, but it was an outcome,” says Strozzi. “The soldiers who’d been through the program had learned to carry themselves in a way that inspired greater confidence and trust. Because they were calmer, they were much better in a crisis. Because they had more awareness of what triggered their aggression, they took more responsibility for their actions. Plus, they were far more attuned to what other people were thinking and feeling. All these changes translated into a leadership presence.”

Fort Devon inspired Strozzi to begin thinking about how he might adapt the program for business and government leaders, bringing 21st-century military practices to the civilian sector. In doing so, he stands as part of a long tradition. Classic industrial-era behemoths such as General Motors, Ford, and IBM modeled their structure, operations, and internal development processes on those of the industrial-era military. The top-down emphasis on command and control and the compartmentalizing of strategy from tactics were adopted from military organizations: The brass made decisions and frontline operators executed them. The old Bell System modeled its serried ranks to precisely reflect those in the U.S. Army. “He’s a lieutenant colonel” sufficed to explain where an employee stood. Training was delivered in accord with status, designed to bolster the muscle and efficiency of the system.

But the centralized corporate headquarters and huge industrial plants of that era, like the standing armies mustered to fight conventional wars, were made obsolete by diffuse and weblike technologies, shifting demographics, and deregulated global markets. The military has sought to address the unconventional threats it now faces by emphasizing joint command, network-centric warfare, frontline decision making, and real-time operations. The civilian sector has sought to deal with similar challenges by promoting integrated work teams, matrixing, just-in-time delivery, and more direct means of communication.

The new environment requires leaders who are comfortable being at the center rather than the top, exercising intuitive and collaborative skills rather than issuing commands — leaders whose words are consistent with their actions. Strozzi’s military and civilian students and clients use the practices he has refined to develop an internal balance that manifests itself physically, an advantage in a world that values authenticity over positional power.

In the Dojo

On a gusty December day in 2006, a disparate crowd gathers at the ranch for an advanced leadership program: a few pharmaceutical executives, several “high potentials” from West Coast tech firms, a martial arts master from Jakarta, a professional race-car driver, and the head of a partnership for social justice. On entering a barnlike wooden structure with floor matting, sweeping windows, and lethal-looking staffs arrayed along the walls, people remove their shoes and start to limber up.

Strozzi enters, lithe and graceful, and moves to the center of the room. “Listen up,” he says briskly, more coach than teacher. Everyone forms a circle and listens as he outlines the program for the day. The session will start with an exercise that helps participants test the power of their spoken commitments, their ability to translate ideas and beliefs into actions that can be practiced until they are embodied and compel belief.

People pair off. “Take time to look at your partner,” says Strozzi. “Feel the ground under your feet. If you’re not grounded, you can’t establish intimacy. Put your hand on your partner’s chest. Do it with conviction. Feel how he or she is breathing. Tell your partner one thing you are committed to doing. Practice it a few times, being concise and clear. Then ask your partner to describe what he or she feels from you when you’re talking. Maybe you think your declaration is straightforward, but your arm collapses when you speak, or your eyes shift. Your somatic being has to support your message. If it’s not aligned with your words, people won’t believe you. You can’t say ‘trust me’ and then lean away.”

The next exercise is a “two-step,” in which everyone executes a series of simple moves before the group. “Step into the center, then turn. Speak your commitment as you walk forward. Then do it again three times.”

A software manager volunteers to go first. She takes a deep breath and declares: “I am committed to helping my team through our latest reorg.” As she speaks, she walks down the line. People watch intently. A young man who has joined a nonprofit straight from the military speaks up. “Can I give you some counsel? It seems to me that you are hurrying when you walk. That way of moving could undermine the commitment. Your people could read you as being too rushed to give them clarity or support.”

“I didn’t realize I was hurrying. Thanks.”

Nancy Hutson, the former Pfizer executive, tells the class how her team used a two-step to develop trust and cohesion. “We start with a premise: We are moving together to find new medicines to bring to people. Then we practice moving together as we say it. We coordinate our gestures until we kind of catch a wave, a place where we’re all breathing together and moving in the same rhythm.”

Strozzi asks, “What does that do for you?”

Hutson answers, “It enables us to embody our commitment. That helps us be a team in a deeper, more connected way. Something happens when you bring your body to work. You are more whole, so people see you as more authentic. I also think this is effective with our team because we’re all scientists. We want to know the how of things, verify results, check interpretations. If we can physically feel one another breathing slowly and moving firmly, it gives us confidence in what we’re doing. If we’re moving frantically or being in our heads, we know we’ve got a problem. This stuff is real, based in the physical world. It’s data, and scientists want data.”

The day finishes with a rondori exercise, in which everyone moves randomly all at once. Without warning, individuals approach one another. Those approached can either accept by linking arms and moving forward alongside the person or refuse by turning the person aside and moving him or her in another direction. The exercise begins chaotically, with people crashing into one another. Refusals are awkward, leaving those who made them uncertain where to go, how to walk away. Strozzi takes his time, watching with focused attention, then steps to the center of the room and says, “Come at me.”

People do. He intercepts them, harmonizes with their movements or turns them away, remaining consistent and firm in every encounter. “We respond with strength and compassion whether we’re accepting the request or not,” he says. “People feel you in relationship based on how you are physically present with them. That’s more important than your words.”

In traditional aikido, a rondori is a sustained and simultaneous attack on a single person, with students and masters attempting to throw the individual to the mat or pin him or her down. The rondori was what first suggested to Strozzi that aikido could be adapted to help people in organizations. “I realized that rondori is what life is like at work these days, stuff flying at you, all the e-mails and endless requests, that experience of constant bombardment. Doing a rondori exposes your habitual responses to pressure — withdrawal, tightness, over-accommodation, over-responsiveness, fear, desire to dominate, coldness — so you can see how you handle it. It gives you a chance to practice a different way to respond, so you can keep your dignity, act with clarity, maintain your awareness. Practicing helps you develop the musculature for effective action.”

Supporting spoken commitments with physical presence is a way of “putting it on the mat,” aikido-speak for expressing one’s philosophy through skilled and conscious action. In a traditional dojo, putting it on the mat involves hand-to-hand combat. But in Strozzi’s leadership dojo, the principles of aikido are interpreted to support awareness: There are no locks, no pins, no flips, no holds. The sequence of movements that distinguishes aikido — responding to aggression by entering into the center of an attack, blending with its energy, and guiding the attacker to a neutral place –– are adapted for a nonmartial context.

The day at the dojo is full of action. Only at lunch do students sit down. It’s a departure from the typical leadership development class, where people listen to a speaker, take notes, write down commitments, and discuss what they have learned. “People in organizations don’t move enough,” says Strozzi. “They don’t engage their bodies. In the dojo, we do everything standing up. When you’re standing, you can move. Being human is about standing up. Assuming a vertical posture is what set humans on their evolutionary path. It’s what makes us distinct, gives us our power. It’s our way of staying aware.”

Taking It to the World

Colonel Krawchuk believes that building awareness is essential because the U.S. military services have grown so diverse. “This makes it harder but also more important to be aware of what others are thinking, and how what you do impacts them,” he says. “If you don’t know how to pay attention, you can’t influence people who have different experiences from yours. Then the whole leadership thing just falls apart.”

Krawchuk took personal time to study at Strozzi’s dojo before accepting an assignment at an operations center in Germany. “We did training in logistics for Special Forces guys who operated rescue helicopters, so we were dealing with an atmosphere of constant crisis,” he recalls. “Being in crisis intensifies the need to remain centered. The trouble is that operating in crisis mode tends to make you go to your head. So you lose balance physically and can’t think straight.”

Krawchuk observes that counseling people in this kind of job is less effective than working with them through movement: “It provides a way to get them to slow down so they can see their own behavior, see the effect they have on people around them. Now when I do performance counseling, I always start with movement. I grab a guy and say, ‘Let’s go for a walk.’ While we’re walking, we do centering exercises. That takes them out of their heads and into their bellies. I have them observe how their feet are on the ground, see where they are breathing. This enables them to settle down enough to address whatever the issue is in a calm and powerful way. The somatic aspect makes the difference.”

Now Krawchuk is working with Strozzi to integrate somatic practice into counterinsurgency training. He says, “Counterinsurgency has been defined as 70 percent civic affairs and 30 percent kick down the doors. In recent years, it’s been the reverse, which is a problem. You see it in companies, too. Enron was about 70 percent kick down the doors. People in business look to the military for training ideas, but the ‘business warrior’ approach trivializes both business and war. What we really need to do is change the mind-set.”

With Krawchuk, Strozzi has begun readapting some of his civilian leadership training techniques for the next iteration of military application. Strozzi says, “Security problems these days require an interdisciplinary approach. So the focus in the military is on connecting across cultures. Working with the body gives you a way to do that because it transcends words and language. It takes us to that common core of being human.”

That common core is what attracts Krawchuk. “Using awareness helps people identify kindred spirits in different sectors so they can figure out who to blend with,” he says. “The army needs to do that in order to create grounded leaders who manifest values that are attractive to lots of different people. If we can’t, we won’t raise the resources we need to address our security problems. It’s not about killing bad guys anymore, it’s about seeing problems in an integrated way.”

Drawing on military connections, Strozzi has been expanding his leadership dojo concept to the Philippines and Indonesia, which are on the front lines of security issues today. He says, “There’s a huge youth bulge in Southeast Asia, a boom in kids ages 13 to 19, mostly in rural areas with few opportunities but with enough media to show them what life is like in the city and persuade them to go looking for work and excitement. They leave their villages and get scooped up by groups like al Qaeda, put into madrassas for indoctrination. We want to open up dojos for these kids where they can learn aikido, focus on being centered, on harmonizing instead of confronting. It’s the polar opposite of what the madrassas teach, but it draws on the culture in this part of the world in a powerful way. These countries have a long history of excellence in the martial arts. That gives us a framework for building authentic leadership based on what’s best in these kids so they can help defuse the aggression that is making the world so dangerous just now.”

In aikido, the ability to manage an attack skillfully derives from self-knowledge. To quote Sun Tzu, author of The Art of War:

And so in the military —

Knowing the other and knowing oneself,

In one hundred battles no danger.

Not knowing the other and knowing oneself,

One victory for one loss.

Not knowing the other and not knowing oneself,

In every battle certain defeat.

Richard Strozzi-Heckler takes these precepts and adapts them to the leadership challenges of our era, for both military and civilian organizations, helping each sector learn from the other. What they learn today is different from what they learned from one another in the industrial era. The difference can be summarized in one of the classic commentaries to Sun Tzu: “For the skilled general, victory is attained before the battle is joined. He awaits the moment. A military that rushes to the fight, hoping for victory, assumes the ground of defeat. Blend and harmonize.” ![]()

Reprint No. 07406

Author profile:

Sally Helgesen (sally@sallyhelgesen.com) is a leadership development consultant and author of five books, including The Female Advantage: Women’s Ways of Leadership (Doubleday, 1990) and The Web of Inclusion: Architecture for Building Great Organizations (Currency/ Doubleday, 1995). Her Web site is www.sallyhelgesen.com.