Best Business Books 2008: Life Stories

A Master Class in Leadership

Steve Weinberg

Steve Weinberg

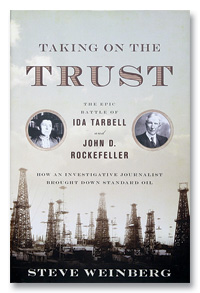

Taking on the Trust: The Epic Battle of Ida Tarbell and John D. Rockefeller

(W.W. Norton, 2008)

Willie Brown

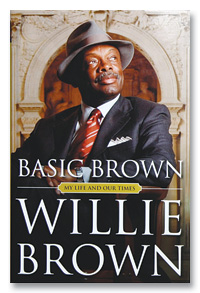

Basic Brown: My Life and Our Times

(Simon & Schuster, 2008)

Jacob Weisberg

The Bush Tragedy

(Random House, 2008)

Ted Sorensen

Counselor: A Life at the Edge of History

(HarperCollins, 2008)

Stories of real lives draw their power from authenticity, engagement, and example. Whether these stories are told by the subject, an insider, or an independent researcher who was not even born when the events occurred, it is their reality that touches, teaches, and inspires us. This year, the legitimacy of the genre repeatedly came into question, but there were outstanding examples that reminded us of the singular importance of actual life stories, honestly examined.

Autobiographies filled the headlines in 2008, and not in a good way. Several highly touted memoirs were revealed to be frauds — not just exaggerated but completely made up. More than 10 years after publication of Misha: A Mémoire of the Holocaust Years, by Misha Defonseca, an award-winning book about the author’s experiences as a Jewish child hiding out from the Nazis and for a time literally raised by wolves, it was revealed that Defonseca was a Catholic and that none of it happened. Love and Consequences, by Margaret B. Jones, a memoir of being raised by a foster mother and being a gang member in South Central Los Angeles, was critically acclaimed, too — until it was revealed that Jones (real name Seltzer) grew up in a suburban family home and attended private school.

A credibility problem of a different kind arose from the book that sparked the most Weblog posts of the year: What Happened: Inside the Bush White House and Washington’s Culture of Deception, by former White House press secretary Scott McClellan. It is the most recent in a long, rich tradition of Washington self-exonerating payback books, the kind that are read index-first inside the Beltway. It is also an un-spinning, or perhaps re-spinning, from a professional spinner that directly contradicts much of what McClellan told the press and the American public.

The memoir elicited many a smug “we told you so” from those delighted to hear a “Bushie” admit the president was uncurious and more focused on politics than reality. And there were howls of outrage from the White House, insisting that the book was just sour grapes from a man who was pushed out of his job. But what are the rest of us to believe, what McClellan said then or what he says now? A hint for parsing this genre: Look for the subject of the verb. “In these pages, I’ve tried to come to grips with some of the truths that life inside the White House bubble obscured,” writes McClellan. It does not count as “coming to grips” if the second part of the sentence omits any clue to causation or sense of responsibility. The treatment of mistakes and critics is another key indicator of validity and value in this genre. “It strikes me today as an indication of [the president’s] lack of inquisitiveness and his detrimental resistance to reflection, something his advisers needed to compensate for better than they did,” writes McClellan. Shouldn’t that be “better than we did?”

The real challenge to biographers and autobiographers is not the outright frauds but the bias inherent in any selection and presentation of facts. Biographer Kristie Miller notes, “A biographer’s greatest challenge is not to put in everything he or she knows,” and she quotes Lytton Strachey on how the craft of biography should aim for “a brevity which excludes everything that is redundant and nothing that is significant.” The appropriate proportion and context is just as essential as the names and dates.

Setting the Bar

The idea that biographies and memoirs should be true is relatively recent. In a fascinating March 2008 New Yorker article titled “Just the Facts, Ma’am: Fake Memoirs, Factual Fictions, and the History of History,” Harvard Professor Jill Lapore shows that the separation of fact and fiction, and the idea that facts should be objective and documented, is only about 150 years old. This confirms “muckraking” journalist Ida Tarbell as a pivotal figure in the genre.

Tarbell (1857–1944) helped establish our modern notion of a biography with her meticulously researched and documented books about Napoleon and Abraham Lincoln, and especially with her 815-page biography of John D. Rockefeller and the Standard Oil Company. That book not only led to the enactment of the antitrust laws and the breakup of Standard Oil, it transformed our notion of leadership in the private sector. Explicitly premised on Ralph Waldo Emerson’s assertion that “an institution is the lengthened shadow of one man,” The History of the Standard Oil Company (1904) laid the foundation for current notions of corporate and political leadership and the impact that leaders have on their organizations and the larger economy and culture. Her book on Rockefeller was personal without being gossipy, critical without being shrill.

Investigative journalist Steve Weinberg, in Taking on the Trust: The Epic Battle of Ida Tarbell and John D. Rockefeller, explains how Tarbell raised the standard for research, documentation, and objectivity and took character-driven narrative and political/cultural critique to a new level. Her innovative approach, insisting on attribution and primary sources for her information, helped define the new concept of investigative journalism — in essence, creating Weinberg’s profession. Perhaps most important, she established an expectation of in-depth scrutiny of public figures and institutions, even corporations, that led to the development of an entire profession directed at guiding and molding public opinion: public relations. Her work also led, of course, to dozens of CEO autobiographies from would-be Lee Iacoccas.

Investigative journalist Steve Weinberg, in Taking on the Trust: The Epic Battle of Ida Tarbell and John D. Rockefeller, explains how Tarbell raised the standard for research, documentation, and objectivity and took character-driven narrative and political/cultural critique to a new level. Her innovative approach, insisting on attribution and primary sources for her information, helped define the new concept of investigative journalism — in essence, creating Weinberg’s profession. Perhaps most important, she established an expectation of in-depth scrutiny of public figures and institutions, even corporations, that led to the development of an entire profession directed at guiding and molding public opinion: public relations. Her work also led, of course, to dozens of CEO autobiographies from would-be Lee Iacoccas.

Tarbell chose Rockefeller as a subject because he was “the Napoleon among businessmen” and because her observation of the impact of his monolithic oil company on competitors and communities inspired her to write about “the processes by which a particular industry passes from the control of the many to that of the few.” There was also a more personal reason: Rockefeller’s market-dominating practices ruined the prospects of Tarbell’s father’s company. But Ida Tarbell’s credibility came from her scrupulous research and her fair-minded assessments. She was critical of the methods used by Rockefeller and Standard Oil, but she also wrote about the strengths of the company and its founder, praising the energy, intelligence, and dauntlessness of both, and she recognized business as America’s singular strength.

Weinberg shrewdly notes that both Tarbell and Rockefeller “established new paradigms for their callings in life. Their reliance on facts was born of the rationalism and scientific outlook that had arisen during the industrial revolution.”

For both, an almost messianic seriousness of purpose and rectitude bolstered their focus and vision. But Rockefeller’s goal was money and power, and Tarbell’s was justice. His goal was structure and stability; hers was adventure and social change.

An even more significant distinction between the two was their approach to criticism. Rockefeller was offended by it. Despite her firm convictions and sense of purpose, Tarbell welcomed criticism, even insisted on it. That is not only the best guarantee of the validity of her assessments, but the most important lesson from her example. It is an audacious undertaking to do justice to Tarbell, a superb biographer, but Weinberg’s book would surely earn the approval of even the steely and judgmental author herself.

An even more significant distinction between the two was their approach to criticism. Rockefeller was offended by it. Despite her firm convictions and sense of purpose, Tarbell welcomed criticism, even insisted on it. That is not only the best guarantee of the validity of her assessments, but the most important lesson from her example. It is an audacious undertaking to do justice to Tarbell, a superb biographer, but Weinberg’s book would surely earn the approval of even the steely and judgmental author herself.

Brown versus Bush

Reading Basic Brown: My Life and Our Times, by Willie Brown, the famously flamboyant and always impeccably attired four-term mayor of San Francisco and speaker of the California assembly, is like sitting down for a master class in politics with a large and small p. It is also invaluable for anyone trying to steer any large organization of disparate people who hold even more disparate interests. This is the best playbook for business leaders of all biographies or memoirs published this year and certainly the most entertaining.

Brown was consistently criticized as a wheeler-dealer but was also consistently reelected by his constituents. His response to criticism about his tactics or about standard career killers, such as having a child with a woman he was not married to, was to admit the fact, explain his position, and find common ground. In the book, as on the stump, he is candid and pragmatic: “Ethics fights can be finessed, but a silly photograph is in your face forever.” And he is undeniably effective.

Many of Brown’s ideas run counter to conventional wisdom. He believes that competence and reliability are more important than party affiliations or platforms. He kept his legislative agenda private because it allowed him to negotiate with those who would have had to oppose him if he had made it public too soon. He took money from everyone, paraphrasing California politician Jesse Unruh: “If you can’t take the lobbyists’ money, eat their food, drink their booze, sleep with their women, and then vote against them, you don’t belong here.”

Brown’s frank and direct approach to presenting his story is as telling as the incidents and advice he includes. According to his memoir, he always did his homework on the substance and on the politics. He was always prepared but also receptive to “happy accidents.” He took nothing for granted, constantly assessing levels of support. He transcended party lines to establish strong relationships of trust and respect, and any member of the assembly who wanted to talk to him had his immediate attention. He handled sensitive matters privately to prevent embarrassment to an assembly member or a party. And he knew that if an offer sounded too good to be true, someone was probably wearing a wire.

Brown could be ruthless. He describes with great satisfaction the day that five Democratic members of the assembly told him it was time to step down as speaker. While they waited to talk to him, he had them all removed from their positions as committee chairs and evicted from their offices, with their staffs fired and their furniture put out on the street. Later, however, he reassigned them all important, though lesser, positions. “I never cut any one out entirely,” he writes. “They might be renegades today, but I regarded myself as in competition for their votes in the future.” Brown never let party affiliation, history, or grudges impede future effectiveness.

In The Bush Tragedy, by Jacob Weisberg, George W. Bush comes across as a more-partisan and less-effective politician than Brown, albeit far more powerful. Slate editor-in-chief Weisberg assembles an authoritative dossier on the 43rd president in support of his psychological assessment of Bush as a man whose goal was achieved when he was sworn in. After that, Bush’s inability to be introspective and his impatience with subtle complexities produced reactions and decisions that were superficial, even thuggish. Weisberg comes to some of the same conclusions as McClellan, but they are more credibly documented and the illustrations are more illuminating than condemning.

The book is a cautionary tale about the difference between the qualities that get someone a job and those that it takes to do the job. And it is the story of the consequences of the inability or unwillingness to learn from mistakes and criticism. Weisberg describes Bush as “mulish” and “a man of tremendous submerged anger and no patience whatsoever.” He accuses Bush of hubris and describes his presidency as “an Icarus story — the crash to earth of someone who does not comprehend his limits or his motives.”

As often happens with biographers, Weisberg becomes a bit too enamored of his explanation of Bush’s psyche, returning again and again to the template established by Shakespeare’s Prince Hal in Henry IV to portray the president as a onetime party boy who never felt respected by his father. “To state it simply,” he writes, “the Bush Tragedy is that the son’s ungovernable relationship with his father ended up governing all of us.” Although Weisberg underestimates factors that do not support that theory and overestimates those that do, his illustrations are carefully researched, thoughtfully assembled, and lucidly presented. The strength of his book is the thoroughness of his documentation, especially in the chapters about the Bush presidency, a case study in muddled strategy and incompetent implementation. The book’s most important lesson may be that leaders are not necessarily intellectual or reflective themselves, but they will always be evaluated for history by those who are.

The King’s Man

Ted Sorensen is both intellectual and reflective. The title of his memoir, Counselor: A Life at the Edge of History, reflects his focus during his years as aide to John F. Kennedy: a focus more on Kennedy than on himself. Organized thematically rather than in a strict chronology, the book delivers its liveliest and most meaningful prose in sections on speechwriting (a chapter that should be read by anyone who ever has to address an audience), the 1960 presidential campaign (remarkably contemporary with special resonance for the 2008 race), and Kennedy’s foreign policy (essential guidance for anyone who is responsible for directing a large organization beset by ambitious competitors — or who wants to be).

Sorensen describes Kennedy’s ability to inspire hope and communicate a sense of possibility as a crucial factor in gaining the confidence and support of the voters and his staff, and the implied parallels to Barack Obama make these passages particularly relevant. Sorensen’s candor about his mistakes, and Kennedy’s, and the sincerity of his regret on both counts, are notable, especially when he apologizes for Kennedy’s failure to censure Joseph McCarthy. (For another perspective on Sorensen, see “The Art of Influence,” by Michael Schrage.)

The book’s most fascinating moments are the descriptions of Kennedy’s decision making during the Cuban missile crisis, the Bay of Pigs invasion, and other turning points, for better and worse, during his administration. Sorensen makes us see how Kennedy accepted responsibility for his mistakes and learned from them. It was the failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion that caused Kennedy to change the way he was briefed on his options and change the way he evaluated what was presented to him. His insistence on better quality and depth of information and his demand for a wider range of choices were essential elements that made the difference during the missile crisis the following year.

This memoir reads like a cross between a gripping spy novel and a Harvard Business School case study. Sorensen’s graceful insights remind us how the best and most honestly told life stories illuminate and inspire our own. ![]()

Nell Minow is editor of the Corporate Library, an independent corporate governance research and rating firm, and movie critic for Beliefnet, a spiritual Web site, and for radio stations across the U.S.