Privacy in the Age of Transparency

A tough customer ethic demands corporate openness and integrity.

(originally published by Booz & Company)

|

|

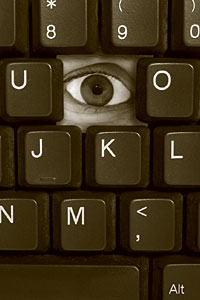

Photograph by Opto Design

|

The incident occurred in 1999 when Amazon.com introduced purchase circles, an online marketing tool that, supposedly for the customer’s benefit, revealed what books Amazon’s customers from some well-known corporations were buying. For example, customers from Microsoft, it appeared, liked to read The Microsoft File: The Secret Case Against Bill Gates, by Wendy Goldman Rohm, a book that was critical of top management at the software giant. A book about operating system upstart Linux was a hit at Intel.

IBM favorites were also exposed on the Amazon site. As a group, IBM employees weren’t reading anything particularly heretical, but Big Blue’s then–chief executive Louis V. Gerstner Jr. didn’t like the voyeuristic aspects of the purchase circles, and polled IBM’s workers for their reactions to Amazon’s new program. Mr. Gerstner was inundated with 5,000 e-mails within hours; more than 90 percent expressed displeasure about having their corporate book-buying behavior displayed online. Mr. Gerstner passed this finding along to Amazon, and IBM was removed from the purchase circles.

As an embarrassing coda, an excerpt from a letter Mr. Gerstner sent to Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos was leaked to the New York Times. In it, Mr. Gerstner cautioned: “I’m certainly not going to tell you how to run your business, but I do urge you to view this as an enormously important issue.”

That anecdote, related by Don Tapscott and David Ticoll in their new book, The Naked Corporation: How the Age of Transparency Will Revolutionize Business, illustrates well the delicate balancing act companies face in satisfying the imperative to provide an increasingly personalized and streamlined relationship with customers, suppliers, and other business partners, and simultaneously keeping the data they’ve collected about them confidential. (See “A New Window onto CRM Success.")

Companies are entering an era of information transparency — a result, Mr. Tapscott and Mr. Ticoll say, of increasingly activist stakeholders, the growing influence of global markets, the spread of communications technology, and a new customer ethic demanding openness, honesty, and integrity from companies. Consequently, risks to privacy are greater, and safeguarding sensitive information has become more significant, and more difficult to do. Among the companies given high marks by privacy advocates for making data protection a priority are Dell, IBM, Intel, Microsoft, Procter & Gamble, Time Warner, and Verizon. Some of these companies — such as Microsoft, which has in the past been plagued by security leaks in its operating system and e-commerce programs — have embraced hard-line privacy stances only after experiencing first-hand the potential damage to their businesses that privacy breaches can inflict.

Business-to-consumer companies that fail to protect customer data can lose the trust and loyalty of customers, and drive them to other companies with which they feel more comfortable sharing personal information. That, in turn, has the somewhat ironic effect of providing privacy-friendly companies with the greatest aggregate database of valuable demographic, purchasing, and financial information about customers. This sensitive data can be a goldmine for cross-selling additional products and targeting direct mailings on the basis of customer preferences — as long as these sales campaigns are handled gingerly so that consumers feel that their privacy is respected.

There’s persuasive evidence that consumers are becoming even more protective of their personal information with the increased prevalence of Internet shopping and the aggressive data collection about shoppers by consumer product companies. The most thought-provoking statistics have been published by Privacy and American Business (P&AB), a monthly newsletter cofounded by Alan F. Westin, the well-known information privacy expert and professor emeritus of public law and government at Columbia University. P&AB is published by the Center for Social & Legal Research, a data protection think tank. According to the research in P&AB’s September 2003 issue, 36 percent of the American public, some 75 million adults, call themselves “Privacy Fundamentalists.” These are people who are passionate about threats to their privacy by businesses and favor government regulation of corporate information practices. That’s a huge leap from 2000, when only 25 percent of respondents to a similar survey fit this category. Moreover, in 2003, P&AB found that 53 percent of Americans (10 percent fewer than in 2000) could currently be categorized as “Privacy Pragmatists,” that is, people who will freely exchange personal information if the benefits they receive are perceived as greater than the privacy risks they’re taking.

Professor Westin used other survey data to explain the increase in Fundamentalists and decrease in Pragmatists and to draw the following conclusions: Fifty-six percent of Americans don’t believe most businesses handle consumers’ personal information in a manner they consider to be proper; 59 percent do not think the existing mixed public–private system of protecting consumer privacy is providing a “reasonable” level of assurance.

Consumers have adopted these beliefs after being exposed to a growing array of privacy intrusions. Since 1990, 33.4 million Americans have been victims of identity theft — in this case, defined as the theft of personal information with the intent to use it for fraudulent purposes. Half of these crimes occurred in the last two years, according to P&AB. There are also many disconcerting ways individual privacy is invaded. It’s impossible for individuals to use the Internet without being interrupted by cookies-based marketing piggybacking on Web surfing and purchasing habits; video and biometric surveillance is unavoidable in public places and at work; and in numerous instances, medical and financial databanks have leaked personal information and cost people their jobs, reputations, or both.

The scale and impact of these unwelcome trends is chronicled extensively in Database Nation: The Death of Privacy in the 21st Century, by longtime privacy activist Simson Garfinkel. In this book, Mr. Garfinkel is implacable about the importance of privacy to individuals and why people are so protective of it: “Privacy is about self-possession, autonomy, and integrity…. Over the next fifty years we will see new kinds of threats to privacy that don’t find their roots in totalitarianism, but in capitalism, the free market, advanced technology, and the unbridled exchange of electronic information.”

That statement may be a bit harsh, but the P&AB surveys, as well as other recent polls, indicate that consumers share many of Mr. Garfinkel’s concerns. Somewhat surprisingly, considering the depth of consumer wariness, this attitude represents an opportunity for companies, if they’re willing to develop robust privacy programs. This is a central theme of The Naked Corporation and an earlier book, The Privacy Payoff: How Successful Businesses Build Consumer Trust, by the privacy commissioner of Ontario, Canada, Ann Cavoukian, and journalist Tyler J. Hamilton. Both books argue that the companies that are open and honest in their communications, adopt privacy policies, and are very clear about how they use collected data discreetly to further corporate growth, efficiency, and performance will benefit from wider consumer acceptance in international markets. This, they further argue, is what leads to increased revenue, less litigation from the aggrieved, enhanced reputations for their brands, and more prospective partners willing to enter into lucrative cooperative ventures that require a deep well of trust.

Privacy Payoff points readers to a very powerful instrument for determining how well their companies are complying with fair information practices and to what extent these businesses promote the protection of customer privacy. It’s called the Privacy Diagnostic Tool Workbook (www.ipc.on.ca/english/resources/resources.htm), and it assesses such essential privacy principles as limiting the collection, disclosure, and retention of records; instituting customer consent procedures to opt in or opt out of data-sharing programs; verifying accuracy of records; and protecting data from hackers. In addition, Privacy Payoff’s authors provide a Privacy Impact Assessment questionnaire in the book that companies can use to ensure that new technology — whether databank, biometric security system, video camera, ERP system, or others — complies with privacy requirements.

Importantly, the authors of Privacy Payoff note, privacy policies and systems are just as pivotal to the success of business-to-business relationships as they are to business-to-consumer interactions. More and more companies are entering into joint ventures, either Internet- or extranet-based, to increase efficiency and innovation in supply chains, inventory management, customer relations, and other business operations. As part of these cooperative undertakings, sensitive and proprietary corporate data is shared among all partners. If strict measures and rules are not in place to safeguard private information — such as customer, manufacturing, design, and marketing files — companies can end up unwittingly broadcasting some of their most valuable intellectual assets.

Globalization is another noteworthy factor behind the increased attention being paid to privacy. To do business around the world, companies have had to adapt to local cultures and regulations. Privacy rules vary wildly throughout the globe, and navigating this thicket of laws is critical to international commerce. This is particularly important for American companies, because the U.S. has weak data-protection rules. As a result, a U.S. firm with toothless, but legal, privacy policies could be forbidden from, for instance, sending payroll files or customer purchasing records to an affiliate in a country where shipping data from one place to another is strictly regulated.

Privacy Handbook: Guidelines, Exposures, Policy Implementation, and International Issues, by IT experts Albert J. Marcella Jr. and Carol Stucki, provides an overview of global data protection regulations and laws, and a large number of resources for staying on the right side of them. The book’s country-by-country breakdown of privacy regulations is particularly well researched, covering small nations as well as large ones. Bulgaria’s constitution explicitly states that “the privacy of citizens shall be inviolable,” and in 1997 Bulgaria enacted a tough Personal Data Protection Act. This law requires that organizations collecting personal information must inform people why their data is being gathered and what it will be used for; allow people access to information about themselves and give them the right to correct it; ensure that the information is securely held and cannot be improperly used; and limit the use of personal information for purposes other than the original reason unless they have the consent of the person affected.

The effort that Bulgaria and other nations with similarly tough policies have put into enacting strong privacy policies places in stark relief how little the U.S. has done: The term privacy doesn’t appear in the Constitution, and no specific set of laws in the U.S. governs the level of data protection companies must provide. In fact, the lack of mandated privacy safeguards has gotten U.S. companies into hot water with the European Union.

In 2000, after months of negotiation with U.S. Department of Commerce officials, the United States devised a series of privacy policies that reward American firms that voluntarily agree to adhere to them. In exchange for following these rules, U.S. companies have the right to collect data from E.U. citizens, which can include anything from consumer credit information to personnel records of employees at subsidiary operations.

These so-called safe harbor rules, which are essentially a slightly watered-down version of the E.U.’s landmark 1995 Directive on Data Protection and are similar to the four principles in the Bulgaria example, are detailed in Privacy Handbook, Privacy Payoff, and at www.export.gov/safeharbor, a Department of Commerce site. Safe harbor companies are automatically granted permission to transfer data anywhere in Europe, streamlining communications between their U.S. headquarters and overseas affiliates and avoiding the cumbersome process of having to negotiate a potentially stricter privacy contract with each E.U. firm to which they want to send data. To date, nearly 500 U.S. companies have been certified by the Commerce Department as having adopted privacy policies consistent with E.U. requirements.

Few U.S. companies will be able to avoid Europe’s strict view of how data must be protected, say information strategy consultants Michael Erbschloe and John Vacca in Net Privacy: A Guide to Developing and Implementing an Ironclad E-Business Privacy Plan. Japan also recently passed its first omnibus privacy law, which Professor Westin at P&AB accurately describes as “a ‘middle way’ between the industry-sector-based privacy laws of the U.S. and the comprehensive data protection laws of the European Union.” P&AB offers the Guide to Consumer Privacy in Japan and the New Japanese Personal Information Protection Law to explain the data-protection climate in Japan and help companies navigate the legislation.

Although many U.S. companies initially fought consumers’ efforts to make companies pay attention to privacy, almost no major businesses today feel they can completely neglect data protection rules. That doesn’t always mean that leading companies make the right privacy choices. (Recall the JetBlue episode in 2003, in which the airline ran afoul of customers when it shared flight records with a Pentagon contractor that was building a travel security database.) It is also interesting to see how some companies are using privacy to enhance their brand images. The Internet service provider (ISP) Earthlink has run a humorous ad campaign accusing other unnamed ISPs of sharing personal information and promising to be much more discreet. Microsoft has launched a project called Trustworthy Computing, under which chairman Bill Gates has challenged the company to be certain that availability, security, privacy, and trustworthiness are key components of every software and service product the company develops.

These are just a few examples of how seriously companies today look upon privacy. There’s a strong indication that, because of scrupulous motives, strategic imperatives, or the cynical notion that privacy sells, in the future there aren’t likely to be any more embarrassing CEO-to-CEO rebukes like the one Jeff Bezos received.![]()

Reprint No. 04110

Knowledge Review/Books in Brief

by David K. Hurst

Change Without Pain: How Managers Can Overcome Initiative Overload, Organizational Chaos, and Employee Burnout

By Eric Abrahamson

Harvard Business School Press, 2004

288 pages, $26.95

Much of the advice that has been given to corporations about managing change is bad, according to Eric Abrahamson, a professor of management at Columbia Business School. In Change Without Pain, he takes to task the advocates of “creative destruction” and the mantra of “change or perish,” which he suggests has been “overprescribed by gurus for decades.” He argues, as we have also argued in s+b (See “The Four Bases of Organizational DNA,” by Gary Neilson, Bruce A. Pasternack, and Decio Mendes, Winter 2003), that adaptive change is most successful in organizations when it involves the recombination of existing “genetic” elements, rather than the obliteration of the past. Managers will be most successful when they tinker, kludge, and improvise rather than try to reinvent from scratch. Although the resulting change may not be entirely “without pain,” it certainly implies less pain than total reinvention.

To guide the reader through his approach to the incremental change process, Professor Abrahamson develops a two-dimensional “recombinant map” with an organization’s process and structure on the “hard” side and its networks and culture on the “soft.” People are at the center. He identifies three types of recombinant change of escalating difficulty: clonable (the same means can produce the same ends across different parts of the firm), customizable (the means must be modified to produce the same ends), and reinventable (the means must be reinvented to produce the same ends). The recombinant metaphor together with its arcane associations with genetics and genetic engineering may obscure as much as it illuminates, but chapter headings such as these summarize the messages:

-

Redeploying Talent Rather Than Downsizing

-

Reusing Structures Rather Than Reorganizing

The result is a thoughtful, practical book that may act as a valuable antidote to the changeaholics whose nostrums can lead to repetitive change syndrome in their dazed organizations, which soon become resistant to all efforts to transform them.

Signor Marconi’s Magic Box: The Most Remarkable Invention of the 19th Century and the Amateur Inventor Whose Genius Sparked a Revolution

By Gavin Weightman

Da Capo Press, 2003

312 pages, $25

With a wireless revolution now well under way in the computing world, Signor Marconi’s Magic Box, by filmmaker and journalist Gavin Weightman, is a timely look back at the origins of the original wireless technology in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Guglielmo Marconi was the product of an Italian father and an Irish mother. He showed a fascination with all things electrical at an early age, read the scientific journals of the day, and experimented in the attic of his father’s villa. By his early 20s, he had a working system for the wireless transmission of Morse code and had demonstrated the feasibility of an entirely new technology. The news of his breakthrough captured the imagination of the public and investors alike. Marconi soon had his own company, which was financed by his mother’s network of contacts, and secured the patents worldwide that allowed him to carry on with his experiments.

It is surprising to learn just how little Marconi knew about the theory of radio waves and why his invention worked: He proceeded intuitively, scaling up the size of the equipment to massive proportions to transmit messages over longer distances. Progress was rarely smooth: Just as is the case today, there were puzzling losses of signal followed by equally mysterious reconnections. But the new medium received regular publicity boosts as radio began to figure prominently in the broadcast of spectacular news events, such as the rescue in 1912 of the survivors of the Titanic shipwreck.

Unfortunately, Marconi’s gift for science and entrepreneurship had no counterpart in politics, and until his death in 1937, he was a supporter and friend of Benito Mussolini. This lively book does a fine job recounting Marconi’s life and work.

How to Advertise: Building Brands and Business in the New Marketing World

By Kenneth Roman, Jane Maas, and Martin Nisenholtz

Thomas Dunne Books, 2003

268 pages, $24.95

This third edition of a classic aimed at generalist users and creators of advertising services is written in the tradition of David Ogilvy’s Confessions of an Advertising Man. The authors (Kenneth Roman is former chairman and CEO of Ogilvy & Mather Worldwide; Jane Maas is chairman emeritus of Earle Palmer Brown; Martin Nisenholtz is CEO of New York Times Digital) acknowledge their debt to David Ogilvy and his philosophy of research, results, creative brilliance, and professional discipline. How to Advertise is organized in two parts: “What to Say — and Where to Say It” and “Getting the Message Out.”

The style is succinct and to the point: “Advertising is the art of delivering a sales proposition in an attention-getting, involving vehicle and positioning the product uniquely in the consumer’s mind.” The book is also well organized with short chapters and multiple headings and checklists.

The biggest change that has occurred since the previous (1992) edition is, of course, the emergence of the Internet. Although the predictions of the demise of “advertising as we know it” have proved premature, the Internet is having a significant impact (albeit as an enabling technology, not a disruptive one). The authors emphasize the continuity of the Web with other advertising media and the need to integrate the messages into an overall brand strategy.

If you want to catch up on the state of the art in thinking about advertising, you can’t do better than using How to Advertise.

Fortune Favors the Bold: What We Must Do to Build a New and Lasting Global Prosperity

By Lester Thurow

HarperCollins, 2003

340 pages, $26.95

A good deal has been written about globalization and the fate of the world economy from many perspectives — those of economists and financiers, ethicists and anticapitalists. What Lester Thurow, the Jerome and Dorothy Lemelson Professor of Management and Economics at MIT, adds to the debate with Fortune Favors the Bold is a provocative analysis of the problems globalization has created and pungent prescriptions for public policy change.

Professor Thurow sees globalization as an “economic Tower of Babel being built without construction plans” — the outcome of a complex interplay of technologies that gives corporations significantly greater freedom to locate their operations and support functions in countries where they can minimize their costs of production. The resulting dislocation of people and communities is just one of the more visible and disturbing aspects of globalization. Although there is no conscious plan for globalization and its progress seems inexorable, Professor Thurow suggests that its trajectory can be shaped. The result, however, is unlikely to be a smooth curve. Crashes and crises are endemic to capitalism, in his view, a product of its volatile genetic mix of “greed, optimism, and the herd mentality.”

Professor Thurow identifies several sources of current and future economic instability related to globalization, and suggests bold ways to deal with them. One problem is the inability of Japan to clear the rubble left by its economic meltdown in the late 1990s. Professor Thurow’s solution is to liquidate the firms and write off the debts, with the Japanese taxpayer picking up the bill. Another problem looms in the U.S. balance-of-payments crisis and the inevitable fall in the value of the dollar. The risks in the speed of this change, suggests Professor Thurow, can be counteracted only by bold action — reflation in the economies of Japan and the European Community. Another threat is the absence of clear, worldwide intellectual property rights: Here he advocates a vigorous campaign on the part of the U.S. to enforce a new global system of such rights that deals with multiple, often conflicting needs — the need both for cheap drugs to fight malaria and AIDS in Africa, for example, and for pharmaceutical firms to earn high enough returns to develop new medicines.![]()

Jeffrey Rothfeder (jrothfeder@comcast.net) writes frequently for strategy+business and other leading business publications. He is the author of Privacy for Sale: How Computerization Has Made Everyone’s Private Life an Open Secret (Simon & Schuster, 1992). His most recent book is Every Drop for Sale: Our Desperate Battle Over Water in a World About to Run Out (Penguin Putnam, Jeremy P. Tarcher, 2001).

David K. Hurst (dhurst1046@aol.com), a regular contributor to strategy+business, is the author of Learning from the Links: Mastering Management Using Lessons from Golf (Free Press, 2002). A speaker and writer on management, Mr. Hurst also wrote Crisis & Renewal: Meeting the Challenge of Organizational Change (Harvard Business School Press, 1995) and was a visiting scholar/practitioner at the Center for Creative Leadership in Greensboro, N.C., in 1998–99. His writing has appeared in Harvard Business Review, the Financial Times, and other leading business publications.