The Ambassador from the Next Economy

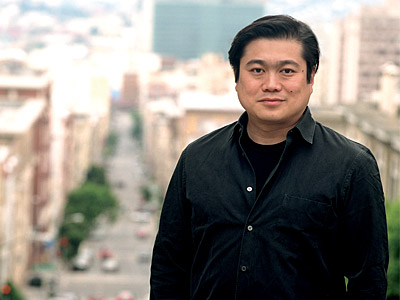

“Venture activist” Joichi Ito has turned his life into a prototype of the organization of the future.

(originally published by Booz & Company)On Joichi Ito’s Web site, there’s a link called “Where is Joi.” Click on it, and a NASA-generated image of the world pops up, with marks depicting his current location (in early June, this was “Joi’s Lab,” his private refuge near the Tokyo Institute of Technology) and his latest habitats. These have included, in recent months, hotel rooms in Toronto, Helsinki, and Shanghai; his sister’s house in Los Angeles; the United Airlines flight between Tokyo and San Francisco (where Mr. Ito says he spends more time than in his own bed); and the offices of dozens of businesses, groups, and friends he visits regularly. The map is not always up to date, but no matter. These days Joi Ito’s mind is most likely to be found online, in a game called World of Warcraft, no matter where on earth — or above it — his corporeal self might be.

Photographs by Vern Evans

World of Warcraft is an immensely popular role-playing simulation, released by publisher Blizzard Entertainment (a division of Vivendi), based in Irvine, Calif. Set in an intricately rendered fantasy world, it pits two immense virtual societies of elves, trolls, wizards, dwarfs, and other creatures against one another in a series of quests, battles, and trading encounters. WoW (as it’s known on the net) has about 6 million members worldwide (more than a million each in China and the U.S.). It amounts to a parallel universe, with clearly delineated political and economic roles, drawing thousands of people from across the globe at any moment to encounter superhuman foes and to form collective “guilds” via their personal computers. Spending countless hours in imaginary warfare may be simply a diversion for many people, but Mr. Ito insists that World of Warcraft is nothing less than an emerging model for organizational design. Given his track record as a venture capitalist and a catalyst for computer-based socially oriented innovation, powerful decision makers are paying attention.

“I’m not a typical venture capitalist,” says Mr. Ito. “Just about everything I get involved in has a steep learning curve, has a lot of unknowns, and has risks. Just as some people are obsessed with money and are willing to do boring things day in and day out to be wealthy, I’m obsessed with always being in a state of wonder.”

Mr. Ito is known in high-tech circles for his uncanny ability to identify the “next big thing” long before other people get to it, and for his quiet but pervasive influence on the development of the Internet. The first Internet server in Japan was housed in the bathroom of his Tokyo apartment, and he played a critical role in pioneering online chat, digital advertising, social network software, Weblogs (blogs), wikis (Web sites and documents, such as the well-known encyclopedia Wikipedia, that allow users to add and edit material), and other interactive media that continue to redefine the limits of communication and community-building. He was among the first to see the real possibilities in each of these technologies; his financial assistance and his advice are credited with helping transform them from a techie plaything for the cognoscenti into broad-based media with social, political, and business impact.

“Joi interprets in deep ways; he’s a profoundly lateral thinker, and therefore he connects the dots better than most,” says John Seely Brown, author of several eminent books on business innovation and the former director of Xerox PARC, the renowned Silicon Valley research center. “He is a hacker at heart, in the best sense of the word. Not only does he go deep, but he also tends to build, or he collects builders around him.”

In 2006, the Internet arguably faces its most comprehensive set of challenges since it was made accessible to the general public in the early 1990s. A series of public debates — on Chinese censorship of search engines, the ability of telephone companies and other Internet providers to charge extra for premium service, the role of governments in providing broadband access, and the future of Internet “uniform resource locator” (URL) addresses — have raised an old question with new urgency: Is the Internet primarily a vehicle for commerce or for community? The way these debates play out, and the policies that result, could make or break a host of businesses and ventures.

In this milieu, Mr. Ito, at age 39, has become one of the most visible global defenders of the idea that commerce and community can be designed to mutually reinforce each other. He argues that the great businesses of the Internet will not be those that stream canned video or data, but those that bring people together as mutual creators, in a kind of “open source” entrepreneurialism. Mr. Ito backs up this idea in part by underwriting the blog companies, participatory Web sites, and other interactive venues for which he is known. He also has become a visible public advocate of legal and technological structures in which standards are open, barriers to entry are low for starting new Web sites or online businesses, participation in online communities is encouraged, new institutions have more freedom to appear and gain influence, and the culture of the Web is integrated with the world at large. At the same time, Mr. Ito advocates acceptance of more pragmatic security-related measures: for example, making organizations highly accountable for online fraud, scams, and other deceptions. All of this has given him an influential presence in global Internet governance circles and in Japan in general: In May, a quietly published book of his conversations with novelist Ryu Murakami rapidly climbed to the sixth most popular ranking in the Japanese Amazon.com store.

The Next Cool Idea

Though Mr. Ito writes regularly (he maintains his own blog journal and recently extolled World of Warcraft in Wired magazine), his most common medium for expressing his ideas is his own frenetic lifestyle. He is the chairman of a Japanese Weblog software company called Six Apart Japan, founder and CEO of the Japanese investment firm Neoteny, and a well-known activist on behalf of open systems. In Japan, where he is now based, he fought unsuccessfully against the national ID card. In the United States, Mr. Ito has focused on protecting the fragile ecosystem of the Web itself. He is an elected governor of ICANN, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers, the nonprofit corporation that controls such mechanisms as the nomenclature of .com, .net, and other URL codes. He also sits on the board of the Creative Commons, a nonprofit organization that is developing more practical alternatives to traditional copyright protection for an online world, like the “some rights reserved” license that allows copying, but with attribution for the original author or artist.

Mr. Ito was also an angel investor in Technorati, a specialized search engine that keeps track of what is going on in the blogosphere — the world of Weblogs — and for this San Francisco–based company, he also has an operating position: vice president of international business and mobile devices. David Sifry, Technorati’s founder and chief executive, says Mr. Ito’s global wanderings make him the perfect person to negotiate with foreign partners, and that he also brings a special visibility to the company as he takes on a more public political role.

In some ways, Mr. Ito’s style foreshadows the changing nature of knowledge work; he moves among many organizations at once, balancing his entrepreneurial individualism against an avid, even obsessive participation in the organizations and communities that interest him, whether online or offline. In one week earlier this year, he advised Yasuo Tanaka, governor of Japan’s Nagano prefecture, on creating a free voice over IP service; kicked off former Sony Chairman Nobuyuki Idei’s annual retreat for senior executives in Hawaii with a talk about how to profit from “free” media; and then flew on to Amsterdam to address a hacker’s convention about open source software strategies. A week later, he was in San Francisco, counseling the lawyers at the Creative Commons on how to balance intellectual property protection with real-world Web usage patterns.

Typically, when Mr. Ito discerns an idea with promise, he founds a company or funds an existing business to capitalize on that promise. Once the business is humming, he walks away to the next cool idea, expressing little interest in the money made on the venture, but continuing to evangelize its potential as a builder of communities and an enabler of public participation.

“This is Joi’s way of working,” says his younger sister, Mizuko “Mimi” Ito, who is a research scientist at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg Center and coeditor of Personal, Portable, Pedestrian: Mobile Phones in Japanese Life (MIT Press, 2005). “He immerses himself in things; he participates. That’s why his way of learning is so different from academics or pundits who tend to talk about things without trying them out. I think Joi gets a lot of street cred because he actually jumps in.”

Indeed, in nearly all of his investments, Mr. Ito has been an obsessive user of the technology before putting any money to work. Typical was his early involvement with Six Apart, the San Francisco startup that created Movable Type, a leading software tool for producing blogs. Mr. Ito started using the program in 2001 and approached the founders in 2002. “I started playing around with blog software,” says Mr. Ito, “and I sort of just clicked about where this was all going to go. Then I blogged like crazy until I understood blogging well. Then I went and met every blogging company worth talking to. I ended up approaching the company that made the software that I was using.”

Even then, the founders of Six Apart — a husband-and-wife team named Ben and Mena Trott — told him they weren’t interested in accepting venture capital. But Mr. Ito persisted. “Joi brought an enthusiasm as a user, which we don’t assume in most investors,” says Mena Trott. “He localized Movable Type in Japanese, independent of any funding. He also donated some money, just as a user; it was probably about $1,500, which was our biggest donation ever. And a lot of our early relationships, like our partnerships with Fujitsu and NTT, were helped by Joi’s connections in Japan.”

Despite his occasional forays into left-wing politics (he advised the Howard Dean campaign on its use of blogs and digital networks), Mr. Ito professes to have no particular political agenda. Indeed, the common theme among his interests and investments is always media and media-created communities. Blogs, wikis, and mass-market role-playing games are all instruments that allow people to communicate and collaborate in depth with people they would never otherwise meet.

“He has a leading-edge insight into communities and the ways they’re using technologies on the Net,” says Lawrence Lessig, the C. Wendell and Edith M. Carlsmith Professor of Law at Stanford, chairman of the Creative Commons, and author of Free Culture: The Nature and Future of Creativity (Penguin, 2005). “These technologies destabilize existing corporate structures, but also create different social and corporate power structures. Joi’s a mixture of anthropologist and activist; he’s uniquely willing to play as both an insider and an outsider.”

Platforms for Cross-Pollination

Mr. Ito has a home in Chiba, in the suburbs outside Tokyo, which he shares with his fiancée, her mother, three dogs, and a cat. But, not surprisingly, he is rarely there. Nor does he spend much time at the offices of the venture capital firm he founded, Neoteny. He prefers to receive visitors in one of Tokyo’s many tearooms. As for “Joi’s Lab,” that’s a nondescript office packed with powerful servers, 30-inch flat-screen monitors, an Internet telephone network, and a massive broadband connection. There is also a cot, for those nights when Mr. Ito stays up too late running raids and managing his guild in World of Warcraft.

Mr. Ito has been crossing boundaries since he was a toddler. Born in Kyoto in 1966, he moved to Canada and then Michigan by age 4, when his father became a research scientist with Energy Conversion Devices (now known as ECD Ovonics), a pioneer in battery technology, semiconductors, fuel cells, and photovoltaics. Mr. Ito’s mother joined the company as a secretary, and so impressed founder and Chief Executive Stanford Ovshinsky that he promoted her through a series of management positions, eventually naming her president of ECD Japan.

An autodidactic inventor and labor activist, Mr. Ovshinsky had a powerful influence on the young Mr. Ito, inculcating him with a fascination for both technology and its humanitarian potential. “He was very active in the Detroit union scene,” Mr. Ito recalls. “So I was always interested in social movements, and I was encouraged to think and read about that a lot.” Mr. Ovshinsky says he regarded the young Joichi Ito almost as his own son, and found him receptive to complex concepts from a very early age — so much so that he put the 13-year-old to work with scientists who needed computer help. “He was not a child in the conventional sense,” says Mr. Ovshinsky. “I could see that Joi was very intelligent, very alert, and very much into technology. No one knew he was a child when he got on the computer.”

At the same time, Mr. Ito says he grew up feeling like an outsider: “Detroit suburbs in those days were a difficult place to be a Japanese kid.” When he was 14, his parents divorced, and he and Mimi, who is two years his junior, returned to Japan with their mother. In Tokyo, he attended the Nishimachi International School and later the American School in Japan, where he became bicultural, as he calls it — comfortable, like many international school students, with “meshing up” different languages and cultures in his everyday life.

After high school, Mr. Ito returned to the United States and attended Tufts University, where he studied computer science and hated it. He dropped out and briefly went back to work for ECD, but Mr. Ovshinsky persuaded him to give college another try. He enrolled at the University of Chicago, with a major in physics, but soon dropped out again, and became a disc jockey in Chicago nightclubs. “I think if I had stuck it out to a Ph.D., I may have gotten to where I wanted to go,” Mr. Ito says. “But I didn’t feel like spending four years solving problems. I was still stuck with professors and assistant professors who were telling me to memorize formulas and not try to understand things intuitively. That just didn’t turn me on.”

After Chicago, Mr. Ito again worked with his mother, who was then acquiring media properties in the U.S. for NHK, the Japanese public broadcasting network. He lugged camera equipment on a number of television and film sets, including The Indian Runner, a movie directed by Sean Penn, and then he began working again for nightclubs, organizing events for them in Los Angeles and Tokyo.

Meanwhile, around 1983, he had begun “playing around with computer networking,” as he later put it, using the teleterminals and early personal computers of the era to send digital messages back and forth on early computer-based conferencing systems.

During this period, a mutual Japanese friend introduced him to Timothy Leary, the former Harvard psychologist and psychedelic evangelist who was anxious to learn more about Japanese youth culture. “I hijacked the situation,” Mr. Ito later wrote on his blog. “After dinner I grabbed Tim and took him on a whirlwind tour of the Tokyo club scene. Tim got excited; he called these new funky Japanese kids ‘the new breed.’ He changed the ‘tune in, turn on, drop out’ [slogan] to ‘tune in, turn on, take over.’” Dr. Leary, after years as a counterculture avatar, had retreated into a relatively staid life as a well-networked pundit in Hollywood and San Francisco technology and media circles. He recruited Mr. Ito as a godson, as he did with anyone he found sufficiently interesting, and introduced him and his mother to the media and technology players he knew in Los Angeles and San Francisco, including John Perry Barlow, a lyricist for the Grateful Dead and early defender of online free speech, privacy, and consumer rights. Mr. Ito returned the favor when Dr. Leary visited Tokyo, and the two at one point attempted to write a book together.

Around 1987, Mr. Ito first demonstrated his propensity to start businesses that cross-pollinate ideas and push media into new realms. He launched two computer companies in Tokyo: a digital graphics business, and a distributor of a group-based communications software package called Caucus. He also tried to launch a franchise of MacZone, a retailer of Apple products, in Japan, but that failed. Then, when he moved with his mother and sister to San Francisco’s Silicon Valley, Mr. Barlow introduced Mr. Ito to John Markoff, a technology reporter for the New York Times. Mr. Markoff gave Joi Ito a copy of MacPPP, the original Internet client software for the Macintosh. To Mr. Ito, that simple program demonstrated how the Internet was about to transform from a scientist and engineer’s tool into a mass media platform. “I got the ‘aha’: This would be a big change for media and much more quickly than anyone thought,” says Mr. Ito.

Soon after, he met the founders of Intercon International KK, an American company trying to offer commercial Internet service in Japan. They couldn’t find space to rent, “so I lent them my wash closet and my bathtub,” Mr. Ito recalls. “We put their router and their connection there and I gave them the room in exchange for free access. I served as CEO of PSINet Japan [the company that acquired IIKK] for a year and eventually helped get them out of my bathroom and into a real office.”

After leaving PSINet, Mr. Ito launched Digital Garage, a Japanese Web solution provider and incubator, which he took public in 1999. Digital Garage split into 12 independent companies, six of which are publicly traded today. He also built Infoseek Japan, which was acquired by Infoseek, which was then acquired by Disney. Today, Infoseek Japan is the third-largest portal in Japan (after Yahoo and MSN), it is profitable, and it continues to grow. “He was really the first of a whole new generation of Japanese entrepreneurs: very international,” says Paul Saffo, director of the Palo Alto–based Institute for the Future, and a member of Mr. Ito’s ever-expanding network.

In late 1999, Mr. Ito’s emerging track record prompted the venture firms J.H. Whitney and PSI Ventures to seed his firm Neoteny (the word means “retention of childlike attributes in adulthood”) with $20 million, to serve as an incubator for new infotech companies. When incubators fell out of favor with the bursting of the Internet bubble, Mr. Ito attempted to transform Neoteny into a traditional venture fund, but he was never entirely comfortable with that role. After funding Six Apart, the blog company, he decided to return the remaining cash to the shareholders and focus Neoteny’s resources on building Six Apart Japan. Since then, besides his involvement with Technorati, Mr. Ito has made personal investments in Socialtext (a wiki for enterprise), Flickr (the photo community site), and other Web-based startups that seek to ease and democratize the creation and distribution of media.

Most venture capitalists invest on behalf of pension funds, endowments, and other deep-pocketed clients. Because they can be personally involved in only so many companies, and because their funds are typically large, they tend to make big bets on fairly established enterprises, often in the multiple millions. And since they must show a positive return within the life of a particular fund, they look for deals with a clear exit strategy, preferably a public stock offering. In contrast, Mr. Ito invests very early, when just a few thousand dollars can make a significant impact, and he says he is less concerned with business models and IPOs than he is with creating something of value to society, whether that is fostering “one-to-many” publishing on blogs or facilitating global virtual communities through chat rooms or multiplayer online games.

“I’ve found that when I focus too much on where the money is, I end up finding fairly shortsighted opportunities,” Mr. Ito says. “But if I focus on looking for people that I like and looking for things that I intuitively feel excited about and just focus on helping those things, then I end up with the best returns.”

An Open Source Life

Most of Mr. Ito’s portfolio companies adhere to the Open Source Initiative, meaning that the underlying source code to the software is freely available and adaptable. But open source is also an apt metaphor for Mr. Ito’s life and work style. When a reporter asks about his whereabouts for the next few weeks, he immediately offers a copy of his computer’s calendar file. His cell phone number is on his blog, so literally anyone can call him; his political writings are published on a wiki so readers can and do edit his content; and although there is no law requiring disclosure of the kinds of private investments Mr. Ito makes, he makes them all public. Maintaining such openness is his way of gaining legitimacy in the world’s eyes without the burdens of authority, but there is a downside. He is too frequently distracted and as yet has not made himself wealthy, he says, noting that he still cannot live off the income from his investments alone.

Of course, not everyone gets through to Mr. Ito, who says that he responds to only a fraction of the calls he receives. Just as a well-regarded programmer’s bit of code is more likely to be integrated in the next iteration of Linux, entrepreneurs or activists with standing in the global online community are more readily granted an audience with Mr. Ito.

“Joi’s very straight,” says Vint Cerf, the chief Internet evangelist at Google, chairman of ICANN, and coinventor of the TCP/IP protocol. “You don’t get any impression that he’s maneuvering. He’s candid, and he’s respectful. In a world of highly political issues, it’s really refreshing. He often provides very useful and practical advice. But he has an idealistic streak, which conflicts with the pragmatic, and I think that causes him a bit of internal turmoil.”

That turmoil was evident in Mr. Ito’s first major step into the political limelight — at the annual Japan Dinner at the 2002 World Economic Forum, held that year in New York instead of Davos, Switzerland. Attending that meeting were such eminences as Nobuyuki Idei of Sony; Yotaro Kobayashi, chairman of Fuji Xerox; Kakutaro Kitashiro of IBM Japan; and Sadako Ogata, the United Nations high commissioner for refugees. Mr. Ito dominated the discussion, blaming the risk-averse establishment elders gathered in the room for Japan’s moribund economy, as the Webzine Slate reported at the time. “The problem with ‘destroy and rebuild’ [the rhetoric then coming from the more radical reformers in the country] is that everyone immediately focuses on the rebuild part,” Mr. Ito said. “What we need to do is just destroy.”

Despite or because of this diatribe, Mr. Ito was invited back in 2003, this time as MC of the event. But if Mr. Idei and the organizers of the Japan Dinner had hoped to temper Mr. Ito’s remarks by this show of magnanimity, they failed. He had been warned, he said: “Don’t talk about complicated issues; the foreigners won’t understand.” Nevertheless, he railed. Reform plans for the Japanese economy read like “Zen riddles,” he declared, and nothing ever comes of them. The bureaucracy is defined by its resistance to change, a system that “rewards people for their obedience” and leaves critics fearing retaliation. (“In fact,” he half-joked, “fear of retaliation is what I’m feeling right now.”) Japan had, if anything, fallen further since the previous year; Mr. Ito called again for revolution.

For a time, Mr. Ito threw himself into Japanese politics with his usual single-mindedness. In 2003, he published an online manifesto, “Emergent Democracy,” which posited that Internet technology could facilitate the development of truly direct democracy. But fervor for political reform in Japan has cooled with the nascent recovery of the country’s economy, Mr. Ito says, and he also came to realize that democracy was broken in many places around the world, making his efforts at home feel a bit parochial. As his interest in politics waned, he also became increasingly fearful that corporate and government powers were moving rapidly to weaken or constrain the very freedoms that made the Internet such a potent democratic tool.

“At a very high level, I’m philosophically disturbed by the damage that aggregation of power and authority causes, whether in big business or the government,” Mr. Ito says. Seeking to foster online communities to counter this type of power, he shifted his activism to organizations like ICANN and Creative Commons, along with several other collective online efforts: the Open Source Initiative; Mozilla, which produces the open source Firefox browser and Thunderbird e-mail client; and Witness, which trains human rights workers to use video cameras to document abuses. He sits on the boards of each of these organizations, as well as that of Wikipedia, the volunteer-written online encyclopedia, and those of most of his portfolio companies.

“He became very interested in my work, and actually started hanging out online with all the Wikipedians in our chat rooms,” says Jimmy Wales, Wikipedia’s founder and president. “He became involved and he edited some articles. That’s pretty unique. Lots of people are interested, but they don’t really dig in and get involved. He’s one of the few people I’ve met, particularly among venture capitalists, who really understand social networks online, and he understands because he digs in and gets his hands dirty full time.”

Meanwhile, among technological entrepreneurs and venture capitalists, Mr. Ito’s not-for-profit work gives him the cachet of being particularly plugged in. “There’s no substitute for such a synthesis of technology, social, and business know-how,” says Mr. Sifry of Technorati. “There’s stuff going on at ICANN, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and Creative Commons that you won’t notice if you’re singularly focused on closing business deals.”

With his latest interest, in World of Warcraft, Mr. Ito is entering a new domain: entrepreneurship within a purely made-up environment. He has no money invested in Blizzard Entertainment, Warcraft’s creator, but the hours he has invested in rising through the game’s rankings would probably have sufficed to produce a doctoral dissertation. And he is constantly in touch via e-mail, online chat, and cell phone with the 250 members of a guild that he cofounded — a diverse body of game characters whose creators are scattered around the globe, across demographic groups and age levels. His “raid leader” is an emergency room nurse; another important player is an unemployed bartender with attention deficit disorder who has gone off his medication; and lately, the 9-year-old daughter of one of his CEOs has been taking part. Keeping these folks on the same page and happy takes a great deal of time.

Long frustrated by the fairly conventional hierarchies in even the most innovative technology companies, Mr. Ito says he sees in his Warcraft guild a new way to organize, manage, and motivate people. With his guild doubling in size every month, he does a lot of learning on the fly. “Every week or so, I have to add a new rank, build a whole bunch of new rules, and throw in kind of ad hoc structures,” Mr. Ito says. “I’m playing with all the different kinds of management ideas I’ve had for companies with a bunch of people who are actually very dedicated. They will set their alarm clocks for 3 a.m. to run a raid of 40 people. They are committed to each other like people in a normal company wouldn’t be committed to each other. So as a test bed for these ideas, this is actually pretty amazing.”

Mr. Ito calls himself “guild custodian,” rather than leader, and he resolutely refuses to exercise power, instead letting solutions bubble up through the guild’s membership. He says he finds that people of widely divergent ages, cultures, and education levels make equally valuable contributions to the guild, and that his authority as founder is used best when used least. And he is absolutely confident a company can be run this way as well.

Even among Mr. Ito’s close associates, the idea that World of Warcraft guilds could represent a management laboratory for companies with real product offerings draws some skepticism, but others say they are sure that he is once again on to something. “Joi has a sense of what toys to prototype with that evolve into serious tools,” says Ross Mayfield, chief executive of Socialtext. “I think a lot of people have now cued in to the fact that WoW and other massive multiplayer games will be the next platform that the Web is evolving to. There are companies that are realizing there’s an opportunity here.”

Management expert John Seely Brown concurred in an April 2006 Wired article that guild management in multiplayer games represents the best kind of job training, as “a total-immersion course in leadership.” Dr. Brown says that he came to this view, in part, by watching Joi Ito. “In the World of Warcraft, much of what you learn is how to improvise or accumulate the resources you need. I see this in Joi: Once he knows what he really has to do, then he becomes incredibly creative in finding resources anywhere in the organization. He never even thinks about the fact that he’s just jumped over three silos. He’s found out how to find who knows what, and how to engage that person to help him. It completely slashes through the barriers in hierarchies.”

Mr. Ito says he expects to launch a new company of his own, its staff recruited from the ranks of his Warcraft guild, as soon as next year. Perhaps they will produce the next great multiplayer game, he suggests, and the organizational structure will be modeled after lessons learned from multiplayer games, a feature he concedes will probably rule out conventional financing. “Most venture-backed and public companies can’t experiment in that space, because investors just aren’t comfortable with it,” he says.

Some associates wonder whether launching another company will satisfy Mr. Ito, or whether his interest in multiplayer games will last any longer than did his interest in blogs. He is attempting, yet again, to complete his education and is studying at the Hitotsubashi University Graduate School of International Corporate Strategy as a candidate for a doctorate in business administration. And he recently launched a weekly show on the MX TV network in Japan, called Technopolis Tokyo. Mimi Ito believes he might have a future in politics if the Web continues to change the nature of politics. If legislators are ever elected like guild leaders, by communities of interest rather than members of geographic sectors, then Mr. Ito might well have a chance of making it into office. In the meantime, as Professor Lessig of Creative Commons suggests, Mr. Ito will continue to play an ever more important role in the evolution of the Internet itself.

“I’m quite certain that 10 years from now, Joi will be at the center of whatever power there is in the Internet culture,” Professor Lessig says. “He’s developing an authority to speak in so many communities that he continues to build social capital.” If the world of commerce becomes as colorful and engaging as a fantasy role-playing game, Joichi Ito’s influence will be the reason.![]()

Reprint No. 06309

Author profile:

Lawrence M. Fisher (fisher_larry@strategy-business.com), a contributing editor to strategy+business, covered technology for the New York Times for 15 years and has written for dozens of other business publications. Mr. Fisher is based in San Francisco.