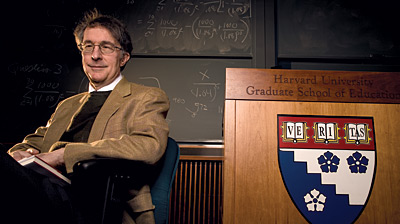

Howard Gardner Does Good Work

The originator of multiple intelligence theory prescribes a code of ethics for business.

(originally published by Booz & Company)What if businesspeople were constrained by a code of professional ethics? What if every executive and manager took a corporate equivalent of the Hippocratic Oath, vowing to “never do harm,” to act “for the good of my customers and shareholders” — and to “not play God with people’s lives”? Harvard Professor Howard Gardner says that this type of credo would make business stronger and more successful. Embracing it would allow business leaders to overcome the perception that they are exploitative opportunists, driven solely by greed.

|

|

Photographs by Peter Gregoire |

The only catch is that the prevailing culture of business would also have to change, starting with the incubators of future corporate leaders — business schools. “It’s striking to me,” says Gardner, “that the university graduate students who most often admit to cheating are the business students.” For Gardner, the kind of careerism that leads a 28-year-old MBA candidate to cheat on exams shows up 10 or 20 years later in fudged numbers, backdated option grants, and indictments. If the culture of business had what Gardner calls an ethical mind embedded in it, then MBAs would routinely consider the well-being of everyone affected by their business when making decisions. They might even rank nonfinancial factors — like a company’s values or its potential impact on the world — on a par with starting salaries when making their career decisions. And there would be less of the narrow, quick-growth-at-all-costs predisposition that in Gardner’s view prevents business from realizing its full potential.

Of course, if businesspeople did think that way, hobbling themselves with Hippocratic Oath–like professional accountabilities, they might lose the freewheeling entrepreneurial creativity that made them successful competitors in the first place. And it could leave them vulnerable to upstart innovators who impose no such ethical drag on their business flywheel. No wonder that Gardner, despite being one of Harvard’s most prolific faculty members, a MacArthur “genius” grant recipient, and one of the most widely recognized authors on leadership, has struggled to make his ideas about “good work” heard.

That may change in 2007, in the wake of Gardner’s 25th book: Five Minds for the Future (Harvard Business School Press). In this work, published in April, Gardner posits five sets of cognitive capabilities that will be needed, he says, by any successful citizen, professional, or businessperson. These include the “disciplined mind,” the ability to focus oneself enough to master a major school of thought such as mathematics, science, or history; the “synthesizing mind,” the ability to integrate diverse ideas into a coherent whole; the “creating mind,” the capacity to uncover new problems and questions, and to solve them; the “respectful mind,” the ability to form and maintain good relationships with other people; and the “ethical mind,” the ability to fulfill one’s responsibilities as a citizen and to identify with fellow human beings.

This catalog of future minds emerged out of a nonprofit foundation called the GoodWork Project that Gardner founded in 1996 with psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi of Claremont University (best known for his 1990 book, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience [HarperCollins]) and William Damon of Stanford University. GoodWork’s researchers conducted 10 years’ worth of studies of outstanding leaders in professions that routinely grapple with ethical concerns, focusing in depth on journalism and genetics, plus law, science, medicine, theater, philanthropy, and business. The researchers asked why some highly capable people follow ideals of service and altruism, and what difference this makes in their careers and lives. The trio’s findings, that ethical practice and great execution tended to correlate, were first published in Good Work: When Excellence and Ethics Meet (Basic Books, 2001) — a book that never became popular. Nonetheless, in an era still marked by boardroom scandals and the lionization of CEOs, the concept of good work represents a kind of undertow, often resonating with senior businesspeople who have been through the mill of a career and are now trying to make sense of their ultimate value and legacy.

“I think that what Howard’s writing about is extremely important,” says John S. Reed, the former chairman of the New York Stock Exchange and former chairman and CEO of Citigroup. “There is an appetite in the business community for his views on leadership, but there is a bit of resistance to the ethical considerations. There shouldn’t be.”

And Bo Ekman, a longtime Volvo executive and now chairman of the Stockholm-based consulting firm Tällberg Advisors, says he finds Gardner’s work particularly timely in light of today’s seemingly intractable global challenges. “We are facing the most horrendous problem of humanity and ecology in the warming of the planet, and we need the best humanistic minds and systems thinkers and designers to develop a civilized process,” he says.

Gardner himself, at age 63, is interested in influencing younger businesspeople, those who will determine the ethical impact of the corporations they manage as they move through their careers. That won’t necessarily be easy; he is not on the faculty of the Harvard Business School and has never taught a course there. He is the John H. and Elisabeth A. Hobbs Professor of Cognition and Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, and he is best known as the creator of the controversial theory of multiple intelligences: a repudiation of the belief that human intelligence can be summed up by purely linguistic and

analytical measures like the intelligence quotient (IQ) or the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT).

His reputation as a business author is based on his studies of the relationship between cognitive development and leadership ability, and the roots of the ability to influence others. His 2006 book on the nature of influence, which, like most of his books, is titled with a pun on “minds,” is called Changing Minds (HarperCollins). Despite the following he has among many educators, the GoodWork Project, and his concept of the ethical mind in particular, represents the only deliberate effort he has made to influence a field. It was motivated in part by his own recent and painful experiences as a kind of whistleblower at Harvard — he was a participant in the ouster of former president Lawrence H. Summers — in which his own ethical mind battled with his personal friendships, and from which he came away with a deepened sense of the resonance between broader accountability and leadership. Self-centered minds will never make effective leaders, Gardner concluded, and he decided he had a responsibility to make that case as compellingly as possible.

“In my previous work,” Gardner says, “I never spent any time proselytizing. But with Good Work, my inclination is to be much more activist and to convince people in business that we have a real problem. I sometimes say to businesspeople, ‘The reason you won’t [pay attention to this idea] is the reason you should.’”

Earned Relevance

Ethics is a luxury, says one of Gardner’s classroom students — a woman in her mid-20s. Businesspeople, who must do whatever they can for money, can’t afford it. “Isn’t ethics reserved for people in prestigious professions, like the journalists and geneticists you studied?”

Gardner isn’t buying it. “Getting good service at a hotel isn’t quite the equivalent of surgery at the Mayo Clinic, but I think it’s selling people short to claim that good work is associated only with a high-status job,” he says. He goes on to say that people are not machines, and thus many find ways to bring an ethical awareness or personal engagement to jobs that others would consider rote or even demeaning.

That is one of the core messages Gardner tries to get across in the GoodWork seminar he teaches. On an afternoon in September 2006, the dozen students squeezed into tiny desks in a School of Education classroom near Harvard Square are a mix of Ph.D. candidates and veteran teachers taking a year or two off to earn their master’s degrees before returning to public school classrooms.

These students are deferential to their mentor, who slouches at the front of the room, sipping from a plastic bottle of Coca-Cola that never seems to leave his side. Among his students, colleagues, and friends, Gardner is known for his lack of pretension. His eyes are slightly crossed, his wiry gray hair seems to have rarely met a comb, his suit looks slept in, and he drives a VW Beetle. Fittingly, he lives his own life by the strict ethical precepts he asks others to follow, believing that there are lines that a professional does not cross, no matter how much money can be made. He eschews junkets of all kinds, avoids the corporate lecture circuit, and has never capitalized on the literally thousands of programs and curricular materials sold in the name of multiple intelligences.

“I don’t think [his style] is an affectation,” says Ellen Winner, his wife, a professor of psychology at Boston University and the author of Gifted Children: Myths and Realities (Basic Books, 1997). “He hates spending money unnecessarily. If his old high school clothing still fits, why waste the time and money to go shopping? But he’s perfectly happy to pay for expensive theater tickets in London.”

In classrooms, at the lectern during speeches, and in private conversation, Gardner is soft-spoken, earnest, and responsive. He shuns hyperbole, glib jokes, and gratuitous theatrics; instead, he listens closely to challenges — indeed, he seems to invite them — and draws on a sweeping range of knowledge about the arts and sciences to respond. (Among the subjects he has written about are the Holocaust, Mozart, and Darwin.) He is also famously impatient, and can come across as aloof and arrogant in some settings just as readily as he can be witty and engaging in others.

The question lingers, considered but not definitively answered, throughout the classroom discussion: Why should business aspire to anything more than maximizing shareholder returns? It isn’t until after class, in a one-on-one conversation, that Gardner elaborates his own answer. The very survival of business may depend on a more widespread benefit. Just as the church of latter-day Europe lost its influence when the mass of society began to doubt its relevance, so too could corporate enterprises be rejected by the body politic — consumers, employees, and even shareholders — if they fail to generate wealth for more than a privileged few. If given a choice, he believes, knowledge workers will flock to companies that embrace high standards of excellence and that allow them to feel engaged with society, leaving other firms with the less talented, less motivated members of the workforce.

Many of today’s young entrepreneurs feel a calling no less intense than that of journalists or geneticists, Gardner says. They also know that a company culture of ethics, engagement, and excellence is more likely to nurture the innovation that markets reward. Thus, the companies that win in the marketplace will be those that enable good work: work that is well executed, contributes to society, and is personally enjoyable to perform. For when ethics atrophy, so does the ability to execute and lead. And when ethics are well developed, people have an inner gyroscope they can rely on for guidance as they confront the complexities of the business environment.

In making this case, Gardner fits comfortably within a long line of corporate humanists dating back to Mary Parker Follett in the 1920s. In more recent decades, chief executives like Max De Pree of Herman Miller, Anita Roddick of The Body Shop, and Yvon Chouinard of Patagonia have run highly successful companies with processes and practices that follow ethical precepts. Google has professed even loftier values, making its informal motto, “Don’t be evil,” a pillar of its espoused corporate identity. But Gardner goes further still. To him, most business is as inherently corrupt as his students say it is; the drive for competitive advantage and wealth, he argues, has taken business’s attention away from the almost chivalric honor of the professional doctor or lawyer. To be sure, doctors and lawyers don’t always live up to their codes of ethics. But the codes exist, forcing practitioners to confront their everyday ethical dilemmas consciously. This kind of thinking, over time, builds not just individual cognitive capacity for leaders, but also the collective ability of organizations to operate in a more complex world and satisfy the real needs of larger groups of people.

Thus, if Gardner’s concept of leadership could be summed up in the phrase “the mind of the leader” — leadership talent depends on cognitive creativity, he argues — then the core concept of the GoodWork Project could be called “the heart of the follower.” People can’t be expected to transcend self-interest by themselves. In addition to their own values system, they need a high level of ethical awareness that is reinforced by the schools that train them, the organizations that hire them, and society at large. After all, even a highly effective geneticist will have difficulty maintaining his or her integrity when situated in a culture where people don’t take ethical standards seriously (as in a nation with low rates of law enforcement) or when working for a company that doesn’t reward high-quality laboratory practice. Institutions, too, cannot survive outside a general culture of integrity, believes Gardner, because doing so affects the mind-set of employees. Even the most high-minded news organization cannot prevent ethical failures among individuals predisposed to cheat, as plagiarism scandals at the New York Times and the Washington Post have demonstrated over the years.

To Gardner, instilling a values system at all four levels — personal, scholastic, organizational, and societal — is precisely what a profession does. It trains individuals to exercise restraint; it guides and shapes university curricula; it leads the way in condemning or applauding institutional results; and it contributes to the culture (as the countless ethical dilemmas in television shows about doctors and lawyers demonstrate). Business professionals could also play that role, says Gardner; and the argument has brought him into a variety of business-related settings in recent years, where he is not always comfortable. Sometimes his attitude about businesspeople betrays a suspicion of them as a group. (“The one set of interviews I didn’t find credible were the businesspeople,” he told his class about the research conducted for the GoodWork Project. “I felt like we were talking to the public relations department.”) It’s almost as if the nature of business itself, at least as Gardner perceives it, has triggered a war among his own multiple intelligences. Part of him recognizes that to influence businesspeople, he must engage and understand them. And the other part is convinced that they will never get the message.

Mindful Leadership

The disparate fields of cognition, leadership, and education all contribute to Howard Gardner’s view of human ethics. This view grew initially out of two events that happened before he was born. His parents, both German Jews, escaped to the United States in 1938; though they never discussed the Holocaust with their son, the family played host to a steady stream of refugees at their modest home in Scranton, Pa. Gardner’s parents also never spoke of an older brother, Eric, who died in a freak sledding accident at age 7; yet because of this trauma, they discouraged the young Howard from participating in athletic activities. Both of these unspoken stories gave him a feeling of otherness, of being an outsider, though Gardner says he was never unusually shy or friendless. In addition to being cross-eyed, however, he was myopic, colorblind, unable to recognize faces, and incapable of binocular vision. Yet he was a voracious reader, a skillful pianist, and a dedicated Boy Scout, attaining Eagle Scout rank at age 13. His feeling of otherness, mixed with an insatiable curiosity, would later lead him to study psychology, “trying to understand what makes people think the way they do.”

In September 1961, Gardner entered Harvard University as a college freshman. It has been his home ever since. “It was the best thing that ever happened to me; the elysian fields for the mind,” he says. He took more classes than anyone he knew, from Chinese painting to the history of economic thought. He began as a history major, then shifted to social relations, a hybrid of psychology, sociology, and anthropology. He was deeply influenced by the charismatic psychoanalyst Erik Erikson, who became his tutor, as well as by Harvard cognitive psychologist Jerome Bruner, and by the writings of Jean Piaget, the Swiss philosopher and psychologist known for his theory of cognitive development. During Gardner’s undergraduate years, he began what would become a 20-year-long stint as a researcher in an aphasia clinic, working with severely brain-damaged patients. (This experience would become the basis of his first major book, The Shattered Mind: The Person after Brain Damage, published by Knopf in 1974.)

Gardner left Harvard for only one year, 1966, to study sociology and philosophy at the London School of Economics. Returning to Harvard for doctoral work in cognitive psychology, he met the philosopher Nelson Goodman, who in 1967 established a research group at the Graduate School of Education called Project Zero, which focused on systematic studies of artistic thought and creativity. Gardner was a founding member of Project Zero and has remained there ever since, serving for 20 years as its codirector. A so-called soft money institute, Project Zero receives no funding from the university, surviving instead on grants. “It’s been a wonderful petri dish for taking people with some interest in art and some interest in education, giving them a start, and then sending them off,” Gardner says. “We’re great believers in the apprenticeship model of thinking.”

In the 1970s, Gardner experienced his first taste of intellectual controversy with his theory of multiple intelligences. On the basis of psychometric testing results, neurological studies of people with brain damage, and other forms of cognitive research, he disputed the belief — then virtually unquestioned in education — that intelligence was uniformly measurable. IQ tests and SATs captured only verbal and quantitative skills, he argued. But the ability to learn and solve problems depended on a variety of forms of brainpower, including musical intelligence, body awareness, and the ability to understand other people and oneself. All of these were innate in human beings; different people exhibited different combinations of intelligences, he said. A high score on the Stanford-Binet IQ test might be predictive of performance in school, but in no way explained the kinds of intelligences exhibited by musical prodigies, sports stars, or effective salespeople.

The theory, first presented in The Shattered Mind and then expounded in several later books, was roundly criticized by psychologists and educators; but it also helped earn Gardner his endowed chair, his MacArthur grant in 1981, and his place on Foreign Policy and Prospect magazines’ recent lists of the 100 most influential public intellectuals in the world.

Until he was named professor in 1984, Gardner taught at Harvard without even a junior faculty appointment. He preferred to live from grant to grant rather than climb the traditional academic ladder from assistant to associate to tenured professor. This approach gave him the time and support to pick up one research topic after another. His published books included The Mind’s New Science (Basic Books, 1985), one of the first histories of cognitive research; The Unschooled Mind (Basic Books, 1991), a manifesto on school reform; and Creating Minds (Basic Books, 1993), an exploration of multiple forms of creativity. In Creating Minds, Gardner illustrated the seven forms of intelligence with biographical studies of “exemplary creators” in each domain: Albert Einstein (logical-mathematical intelligence), Pablo Picasso (spatial), Igor Stravinsky (musical), T.S. Eliot (linguistic), Martha Graham (bodily-kinesthetic), Sigmund Freud (intrapersonal, Gardner’s term for the intelligence involved with self-knowledge and psychological matters), and Mahatma Gandhi (interpersonal, Gardner’s term for social capability). By the late 1990s, as a researcher and lecturer, Howard Gardner occupied a unique place at the nexus of leadership, education, and cognition research.

Gardner’s ideas, meanwhile, continued to challenge conventional wisdom, particularly among educators. For example, Creating Minds disputed the notion that human beings are born with a capacity for creativity, at least the kind that leads to recognized high performance. Children do indeed know how to play, but achieving sustained creativity requires first mastering a particular domain, whether classical piano or particle physics, which in turn requires at least 10 years of intense study, generally amid a community of supportive individuals. As he writes, “the creator is an individual who manages a most formidable challenge: to wed the most advanced understandings achieved in a domain with the kinds of problems, questions, issues, and sensibilities that most characterized his or her life as a wonder-filled child.”

His next major book, Leading Minds (Basic Books, 1995), represented a departure for Gardner. The book barely references the idea of multiple intelligences. Instead, it portrays well-known leaders as creative changers of minds, using 11 figures — including Margaret Mead, Margaret Thatcher, Alfred Sloan, and Mahatma Gandhi again — to substantiate the point. For example, Sloan influenced the senior managers at General Motors by deliberately demonstrating the qualities he wanted them to have. “His participation in groups,” wrote Gardner, “modeled the kinds of considerations that he deemed important and the model of converging on a decision that he favored.”

In some ways, GM in the Sloan years (1923–56) modeled the kind of professionalism that Gardner went on to call “good work.” He quoted Alfred Sloan in Leading Minds: “We have done a very creditable job for the shareholders, without neglecting our responsibilities to our employees, customers, dealers, suppliers, and the community.” Gardner then added that Sloan was one businessperson whose record could justify such claims, and concluded: “As Americans, [Sloan] was saying, we belong to a society that believes in and fosters business — business where…prosperity for the company can go hand-in-hand with prosperity for the nation as a whole.”

In 2001, Gardner, Csikszentmihalyi, and Damon published their first findings from the GoodWork Project, Good Work: When Excellence and Ethics Meet. Then in 2006, as if in reaction to the lack of response to that work, Gardner published Changing Minds, his study of the ways that people can effectively influence others. Once again using biographies, this time including those of Nelson Mandela, Tony Blair, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush, Gardner posited that any deep and permanent adjustment in other people’s thinking could be achieved only by orchestration of several factors in concert. They include reason, research, rewards, “re-descriptions” (which interpret the facts differently), and the orchestration of real-world events. In effect, he laid out multiple simultaneous pathways for the effective influencer: If you don’t consciously act on several dimensions at once, combining persuasion, the example of your own behavior, and organizational incentives, you will not be able to sway the course of other individuals, let alone larger institutions. And as one small part of Changing Minds made clear, he was thinking about his own organization, Harvard University, in particular.

Ethical Winter

In 2006, Howard Gardner’s love of Harvard and his concepts of effective leadership were both put to the test by the troubled university presidency of Lawrence H. Summers. Though he was one of the few Harvard faculty members who knew Summers personally before his appointment, Gardner also became the first to say publicly that the appointment had been a mistake. He says he found himself in conflict between his own respectful mind, which said that one owes loyalty to a president, and his ethical mind, which said that one has a responsibility to the institution.

“I had known Larry Summers better than probably 95 percent of the faculty,” Gardner says. When Summers became embroiled in public controversies — including his clash with Cornel West, the prominent African-American studies professor, and his famous 2005 speech questioning whether women had the innate ability to compete in science — Gardner says he “became convinced [Summers’s appointment] was a mistake and that he shouldn’t be president. But I probably wouldn’t have said anything if I hadn’t read Robert Rubin saying he hadn’t heard any faculty speaking against him,” referring to the Harvard board member and former secretary of the U.S. treasury. “For two months I didn’t sleep. So I became publicly critical and privately I asked him to resign. I did this with no glee at all.”

Gardner achieved a bit of blogosphere notoriety for his criticism of Summers: He found fault not with the substance of the president’s ideas, but with his governing style. In Changing Minds, he analyzed the conflict between Summers and West as one in which Summers was hobbled by his own inability to give up the idea that “as leader of this flagship institution,” he had control over West. “Unless one has dictatorial powers,” wrote Gardner in a letter about Summers published by the Economist in 2005, “one cannot change an institution by fiat, sheer will, or intimidation. And unless Mr. Summers can somehow reinstate collegiality, trust, and a civil tone on campus he will not achieve his goals, many of which have considerable support within the community.” In other words, Gardner saw the core of the problem as Summers’s own personal limitations as an influencer. Summers “didn’t particularly embody [his stories],” Gardner said later, “and they had no resonance with the audiences he was trying to impress. And every time he made a mistake, it was very costly to Harvard.”

To Gardner, such episodes are challenges to the ethical mind, tests of an individual’s ability to navigate ambiguity. Each time you make a decision on behalf of the larger entity’s welfare (such as Harvard or humanity) instead of basing it on personal loyalty or self-interest, you build your own cognitive capacity. In this regard, just as with the moral dilemmas of medicine and law, the decision to support or not to support Summers, for example, is less important than the exercise of the ethical mind that leads to making the decision. Similarly, companies that focus solely on quick profits, Gardner says, deprive their employees of opportunities to think through complex issues, shortchanging their mental growth. Such companies can rarely produce the sustained innovation that comes only from the unfettered minds of an engaged workforce.

Gardner is currently studying trust — looking first at trust among children. “Not only do we feel that wisdom has disappeared from our society, but that young kids don’t trust one another, don’t trust the media, don’t trust anyone, and it’s very hard to have good work when you don’t have trust,” he says. He is also offering a class through the Institute for Global Ethics at Colby College in Waterville, Me., called Meaningful Work, Meaningful Life. “Young people are looking for positions with companies whose values they share,” he says. “But I think it’s way too early to know if there’s a sea change, or even a pond change.”

Will businesses embrace Gardner’s idea of an ethical profession, a calling? They may, although it’s difficult to imagine too many successful executives agreeing that “Once you’ve given the message that everything is about the bottom line, that destroys expansion of the neural networks.” In the end, however, Gardner is right about at least one thing: The most valuable resource that any company has is the minds of the people who work there, and those minds return the most value when they are encouraged to grow in multiple directions, and to interact in unpredictable ways. ![]()

Reprint No. 07209

Author profile:

Lawrence M. Fisher (fisher_larry@strategy- business.com), a contributing editor to strategy+business, covered technology for the New York Times for 15 years and has written for dozens of other business publications. He is based in San Francisco.