The last mile to nowhere: Flaws and fallacies in Internet home delivery schemes

Investors have risked billions on Webvan, Urbanfetch, and other same-day transporters. The economics, though, show they won't deliver for long.

This article was written with Pat Houston, Anne Chung, Silas Byrne, Martha Turner, and Anand Devendran.

Amazon.com's launch in July 1995 ushered in an era with a fundamentally new value proposition to the consumer: easy access to convenient ordering with seemingly infinite selection. Rather than dropping by the local Barnes & Noble superstore and physically sifting through the 150,000 titles, Amazon's online shopper peruses more than four million titles from a personal computer. Amazon also simplifies the selection process through its search engines and databases loaded with information on millions of consumers. Over the past few years, a host of "category killers" replicated Amazon's "limitless shelf space" model in categories from music, to toys, to home furnishings — while Amazon, in turn, extended to such categories, and others, as well.

Unfortunately, the online advantage is undermined by a benefit only bricks-and-mortar retailers can offer: the ability to walk out of a local store with product in hand. As a result, a new breed of Internet service has emerged: retailers, such as Webvan, Kozmo.com, Urbanfetch, and Pink Dot, that offer same-day delivery. These new e-tailers have staked out "the last mile" delivery to consumers as their basis of competition. By combining the convenience of online ordering with nearly "instant gratification," they offer a new — and potentially superior — value proposition. No one doubts that competition will be fierce. As George Shaheen, CEO of Webvan Group Inc., puts it, "One or two companies will legitimately earn the right to cross into a person's home. We intend to be one of those. I don't believe there will be a multiplicity of companies doing this successfully." (See "Can Webvan and HomeGrocer Deliver Together?" at the end of this article.)

Unlike Mr. Shaheen, we believe the last mile may lead to the gallows rather than to the promised land. Our analysis of the race for Internet-ordering home-delivery services uncovered four fundamental challenges: limited online sales potential; high cost of delivery; a selection-variety trade-off; and existing, entrenched competition.

Before presenting our supporting evidence, we will first briefly profile the new dot-com competitors for the last mile. (Save this scorecard; the game may be a no-hitter.)

Overview of the Players

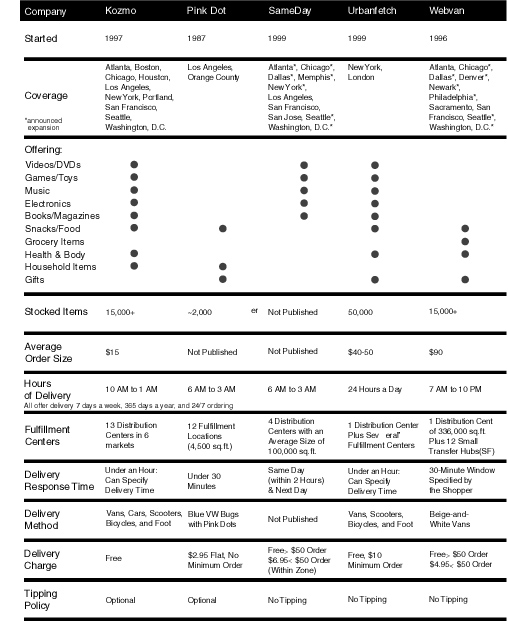

Most of the major e-tailers offering same-day delivery tend to focus on a mix of two broad product categories, immediate gratification/impulse items (e.g., videos, music, magazines, snacks) and routine necessities like grocery and household items, for which many consumers seek to minimize shopping time and effort. (See Exhibit 1.) All offer thousands of items, but order sizes vary dramatically. Not surprisingly, the companies focused on instant gratification/impulse items tend to have the smallest orders.

Exhibit 1: Local-Deliverer Overviews

All offer extended delivery hours. Distribution/fulfillment centers range from simple 4,500-square-foot spaces filled with rack shelving, to highly automated multimillion dollar 300,000-square-foot facilities. Delivery vehicles range from bikes, to scooters, to small cars, to vans — often sporting striking colors and images to market the brand. Though most offer free delivery, some price their offerings to discourage small orders. Also, to ensure that consumers receive truly free delivery, some, at least for the time being, discourage tipping.

Though each company offers a slightly different business proposition, all offer the convenience of online ordering and same-day delivery, thus addressing the time-lag problem encountered in the category-killer e-tailing model pioneered by Amazon.com. These local deliverers hope that gaining control of the last mile will ensure success. We're not so sure — for a variety of reasons.

Limited Online Sales

Given the well-publicized reports about the explosive growth of online shopping, our assertion of limited sales may seem unbelievable. We draw this conclusion by examining how online sales should affect the volume of home-delivery business.

To start, we ran a few numbers. Forrester Research Inc., the most frequently cited forecaster of online sales, suggests the U.S. online-consumer market will exceed $184 billion by 2004 — whopping growth over last year's $20 billion to $30 billion estimate. (No one has exact figures; the government only recently began tracking this new phenomenon.) But according to Forrester, only 60 percent of the 1999 total required physical delivery of goods. Digitally delivered goods, such as airline and event tickets, online brokerage and banking services, plus "researched goods" like automobiles, which have a separate delivery network, accounted for the other 40 percent. The physically delivered categories contribute much of the future growth and account for $132 billion of Forrester's 2004 forecast. To put this in perspective, that's 2.3 times the $57 billion that consumers currently spend annually on catalog purchases. That is enormous growth in a short period of time. But we worry that even that much home-delivery volume will not provide enough sales density to alter fundamental delivery economics.

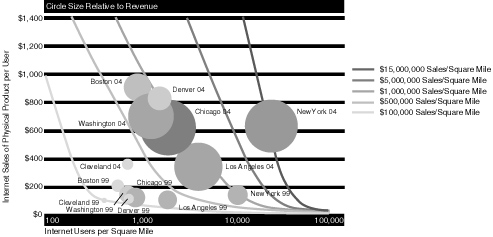

For further perspective we built a forecast model that highlights the two key drivers of local delivery economics: sales concentration and population density. Specifically, we selected a range of U.S. cities — many covered by announced expansion plans from the key local deliverers listed in Exhibit 1 — and examined both current sales density and a forecast for 2004. Our model builds on Forrester's Internet sales forecasts, published data on Internet penetration rates in key cities from Scarborough Research, population and median income data from the U.S. Census bureau, and the one constant: the land area of the cities.

For those not familiar with the consultant's perennial favorite information graphic — the bubble chart — Exhibit 2 warrants more explanation. The horizontal axis indicates the number of Internet users per square mile in each city on a logarithmic scale. (Note that the logarithmic scale represents a tenfold increase in user density for each increment along the scale, rather than the more typical increase of a fixed linear amount.)

Population growth (and in some cases decline) and Internet penetration rates drive the migration to the right between 1999 and 2004. For example, in 1999 an estimated 60 percent of the 4.4 million inhabitants of the Washington, D.C. greater-metropolitan area had Internet access — the highest penetration of any U.S. city. Since the Washington, D.C. area covers nearly 3,500 square miles, those 2.6 million users produce a user density of around 750 per square mile. By 2004, increasing Internet penetration and population growth drives the user density to more than 1,300 users per square mile. The vertical axis estimates the Internet purchases of those users. Again using Washington, D.C., as the example, and looking ahead to 2004, we adjusted the average online sales-per-person to reflect the above average affluence in the district. This yields a projection of online physical-product sales of nearly $700 per user in four years — well above the overall 1999 U.S. average of around $125.

The size of the circle captures an important third variable: market size. Though high user density and high sales-per-user drive sales density, the overall market size also plays an important role.

Exhibit 2: Internet Sales-Density Analysis

For example, Denver, with a user density of nearly 1,300 per square mile and projected 2004 sales per user of $800, will have $1.3 million of sales per square mile per year. Washington, D.C. fares worse with sales per square mile of only $900,000 — but offers a bigger prize due to the greater total population.

The curved lines on the chart highlight different combinations of sales levels and user density that yield the critical value of sales per square mile. The $14 million in sales per square mile in New York City offers an attractive market; even dividing by 365 days per year for the 24/7 Internet economy, the revenue potential totals more than $39,000 per day per square mile.

Unfortunately, after New York, the potential to deliver goods economically in other cities falls quickly. Most major cities offer around $1 million per square mile in sales each year — equal to less than $3,000 per day. And that's the total for all online sales of physical goods, not just the fraction that people want delivered instantaneously. Worse yet, that fraction may have to be shared by several local deliverers.

High Last-Mile Costs

Not only are the sales spread across lots of "last miles," our experience suggests that it costs a lot of money to get there. To demonstrate the economics, we conducted some top-down analyses of one low-cost player and also built a bottom-up cost model for a local delivery business. Extracting from publicly available information, we estimate that Kozmo.com, absent overhead costs such as advertising, currently spends around $10 to make a delivery. Even this cost estimate reflects a heavy bias for its original Manhattan-based operations — the densest delivery area in the country, and thus probably its lowest-cost market. With an average order size of around $15, it's little surprise that Kozmo.com is losing money.

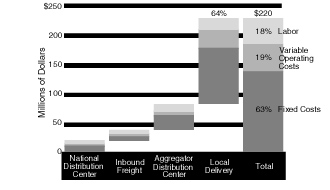

As any New Economy entrepreneur knows, scale offers the obvious solution. But unfortunately, physical delivery does not benefit from the network effect that supports other types of information-economy businesses. As our cost model demonstrates, variable labor costs drive local-deliverer economics, with drivers delivering packages comprising the bulk of the cost. (See Exhibit 3.) A van-based deliverer gets some economies by fully utilizing the vehicle space, but a bicycle courier can carry only a limited number of items. More customers simply means more bicycle trips.

Exhibit 3: Breakdown of Total Distribution Costs

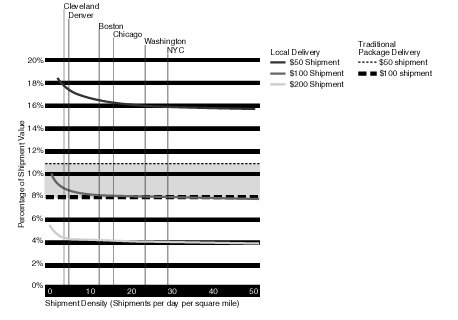

Of course, the impact of the delivery cost depends on the value of the package being delivered. According to Goldman Sachs, an online purchase of $100 incurs an average charge of 8 percent shipping and handling. For $50 orders the research reported an 11 percent charge. As shown in Exhibit 4, increasing shipment density slightly reduces the absolute cost per delivery — but changing the value of the package dramatically changes the relative cost per delivery. For a $100 package, a local deliverer comes close to breaking even with the current average cost for shipping Internet goods. That means a local deliverer that charges standard shipping and handling fees could offer same-day delivery for the same cost as the delayed shipment from a category killer — clearly an opportunity to gain an advantage.

Exhibit 4: Delivery Costs as a Percentage of Shipment Value

Unfortunately, average online orders typically run in the $50 to $100 range, not higher. In fact, larger orders seem antithetical to the notion of instant gratification, which is more about impulse videotape rentals than about, say, the purchase of VCRs. And our research on the current delivery firms shows the companies with the greatest emphasis on rapid delivery tend to have the smallest order size.

New Tradeoff: Speed Vs. Variety

More fundamentally, under current models, the local deliverer resolves the issue of instant gratification at the expense of limitless offerings. To achieve fast response, the local deliverer must hold product locally, rather than in large national distribution centers, as category killers and large catalog retailers do. So the speed advantage gained by Kozmo.com and Urbanfetch.com Inc. means a variety loss. Kozmo offers about 15,000 items in total, versus more than 10 million total items at Amazon.

Even applying the Pareto principle — that 80 percent of the sales dollars come from 20 percent of the items stocked — the local deliverer will be able to steal only a fraction of the total sales volume from a category killer: that represented by high-volume items. Typically, though, high-volume items provide the least profit per unit because of heavy price competition. Furthermore, at least today, the category killer's broader product line provides leverage in negotiating with suppliers. So even though the local deliverer addresses the instant gratification need, it presents a new trade-off of a limited selection. Nothing comes free.

Entrenched Competitors

The biggest challenge to the local deliverers may be competition from both traditional package delivery services — notably the U.S. Postal Service and United Parcel Service Inc. (UPS) — as well as bricks-and-mortar retailers like grocery stores.

UPS and the U.S. Postal Service have the most to lose should local deliverers find a way to make a business out of same-day service. Today, 85 percent of catalog products are shipped via one of these two services; a little more than half of consumer catalog shipments go through the U.S. Postal Service alone. To date, business-to-consumer Internet commerce appears be falling to the same duopoly, albeit in reverse: UPS made 55 percent of online deliveries, according to Zona Research Inc., while the U.S. Postal Service garnered 32 percent. Federal Express Corporation retained the 10 percent share it also holds in the catalog world.

The U.S. Postal Service appears reasonably secure. Unless the federal government pursues the unlikely path of privatization, it retains the sole legal authority to place items in mailboxes, thus monopolizing the base business of mail delivery. Moreover, after investing more than $200 million in a delivery tracking and confirmation system for its Priority Mail product, the U.S. Postal Service has now closed the gap on a key issue limiting its competitiveness with UPS.

Whether the U.S. Postal Service can rise to the challenge of same-day delivery remains to be seen, but national mail services in other countries do so. The Royal Mail provides same-day delivery for Amazon.co.uk throughout London; orders received by noon typically reach the consumer before the end of the day.

UPS, for its part, faces more opportunity than threat from consumer Internet sales. Despite the ubiquitous presence of its brown trucks in suburbia, business-to-business (B2B) delivery still drives the company. Only about 10 percent of UPS's revenue comes from home delivery. Well aware of the upside, UPS has announced plans to provide complete logistics services, from warehousing to order fulfillment, to small- and medium-sized e-commerce startups through its UPS eLogistics business. In informal discussions with major e-tailers, UPS has also described a possible plan to provide aggregator services in 60 cities across the U.S. Both moves indicate a clear unwillingness to concede the last mile to the startups. With an existing infrastructure and the B2B base volume, UPS appears a formidable competitor — one well positioned to partner with category-killer e-tailers, instead of competing against them.

Existing bricks-and-mortar retailers also pose a major challenge to the local Internet deliverer, especially those using groceries as their base-load business. Leading grocery chains, like Lowe's Food Stores Inc. based in North Carolina, now offer online ordering with curbside pick-up at the local grocery store.

The consumer gains the advantages of efficient 24/7 online ordering with no checkout lines, and the grocer avoids the high investment requirements of a home-delivery network. Nongrocery clicks-and-mortar players are also getting in on the game. In May, Barnes & Noble Inc. launched same-day delivery in Manhattan of books ordered online, matching the capability of Kozmo.com and Urbanfetch, and finally linking its physical stores and online presence, thereby leaping ahead of the still-virtual Amazon.com. You can expect more such announcements from category killers in coming months.

The rapid evolution and spread of wireless Web devices might further shift the balance back to the traditional players. A consumer could place an order using a handheld device for pick-up at the nearest store as determined by a Global Positioning Satellite signal. Imagine an out-of-town business traveler looking for a gift to take to her kids back home. Searching the Toys "R" Us Web site, she finds the perfect gift and places the order for curbside pick-up at the store most convenient on her route to the airport. In such a model, retailers with the greatest number of physical outlets could be the most advantaged. And though only 25 million users employ hand-held Web devices today, forecasts suggest a total as high as 1.5 billion in only five years.

New Models Ahead

As the analysis indicates, the last mile consists of some tough terrain: lonely, expensive, and exposed to entrenched competitors. Though we're not ready to ring a death knell for these companies, we do believe they must further evolve their value proposition and focus on the incremental value of rapid delivery. Today, most try to avoid an explicit charge for that. In the future, the companies may need to be more explicit that delivery has a cost — and a value — to the consumer.

We also feel confident that new models will emerge as companies attempt to find the optimal trade-offs to meet consumer needs. In Japan, for example, a very different delivery model has already evolved. Thanks to extremely high delivery density over a relatively small land mass, takuhai-bin services can offer same- or next-day delivery to most Japanese consumers. Also, Japanese convenience stores provide an optional link in last-mile delivery, offering convenient neighborhood pick-up and the option to pay cash — important features given low credit-card penetration and physically smaller mailboxes in that country.

Winning in today's dynamic economy requires a commitment to refine and adapt the business model continuously to meet the ever-changing competitive landscape. Eventually, someone will find a value proposition that works — but many others will fail along the way.

Can Webvan and HomeGrocer Deliver Together?

The $1.1 billion acquisition of Internet delivery specialist HomeGrocer by its rival Webvan underscores the challenge in most current "last mile" business models. Access to capital may have triggered the all-stock deal, but the fundamental operating economics of the delivery business clearly offer a key motivator as well. Last-mile delivery simply cannot support a host of competitors; only by consolidation can these Internet retailers improve their economics and improve their odds of success.

The Economic Impact

Webvan and HomeGrocer have complementary footprints, with Webvan operating in San Francisco and Atlanta and HomeGrocer serving Los Angeles, Seattle, and Portland, Oregon. But expansion plans announced by each presaged competition in such key markets as Atlanta, Chicago, and San Francisco.

That head-to-head contest would have hurt both players. As shown in our analysis, delivery density and average order size serve as the two primary drivers of last-mile economics. Two delivery vans visiting the same neighborhood generates an inherently higher cost at the relatively low sales densities we predict for most urban markets.

Although the combination of the two companies will have no direct effect on average order size, it should propel it indirectly by helping the merged entity address the speed-versus-variety tradeoff. Combining a market's demand into a single distribution center lowers safety stock; to serve consumer demand, the two companies together need carry only as much reserve stock of an item as each would have carried separately. With less inventory investment per sales dollar, the combined entity could expand its product variety, while achieving the same inventory turns planned for the separate entities. This addition of new products offers a means to capture more of the consumer sales dollar and increase average order size.

In fact, broader selection has been part of Webvan's strategy from the outset: Webvan's founder, Louis Borders (of Borders books fame), originally pitched his idea with 3 million stock keeping units; the venture capitalists persuaded him to narrow his focus to the current offering, in the tens of thousands, as a start.

The combined scale of Webvan and HomeGrocer can also prove beneficial in negotiating better prices from manufacturers. Just ask any consumer goods company about the leverage that WalMart's $100 billion in sales provides in negotiations. But, like WalMart, the leverage does not simply result from being bigger and posing a greater threat of switching suppliers. The combined entity requires fewer deliveries from suppliers–and possibly in larger delivery batches — which can reduce costs for the supply base.

Key Operating Strengths

A less obvious benefit of the merger could result from blending the talent pools and alternative perspectives of the two companies. Press reports have highlighted Webvan's automated carousels as a breakthrough in operational efficiency. In reality, these carousels generally hold the slow moving items and accordingly aren't the key to operational efficiency.

Instead, we believe the greatest strength in Webvan's operating model may be its tightly managed cross-dock operations. Described as "stations" at Webvan, these lean neighborhood operations take truckload deliveries from the central distribution center and quickly transfer them to local delivery vans for the true "last mile" to the home.

HomeGrocer employs multiple distribution centers, rather than a cross-dock network of stations, and employs traditional low-automation flow-through racks in its facilities. A combined approach that minimizes the investment in high-tech gadgetry while employing the hub and spoke delivery system could yield a leaner, more effective network, saving the combined company more cash as it continues its nationwide rollout.

A New Category Killer

More speculative is how Amazon.com could benefit from a tighter link with this new, leading "last mile" company. (Amazon owns a 22 percent stake in HomeGrocer). While the public mind still largely associates Amazon with books, the company has continued to expand its product offerings. It's currently the number one e-tailer, and seems on an inevitable collision course with Webvan, which is also adding new product categories.

For Amazon and Webvan, cooperation may be better than competition. Each business currently offers a different and potentially complementary value proposition around the speed-versus-variety tradeoff. Webvan focuses on convenient, tightly scheduled delivery, while Amazon offers massive selection and the ability to recommend specific products based upon user input and buying patterns. Combining forces, the two could increase average order sizes — a critical driver of Internet delivery economics.

Put simply, a category killer offering low-cost scheduled delivery could potentially dominate e-tailing. While both Webvan and Amazon independently aspire to this dominant position, a combined effort could improve the chances of turning aspiration into reality.

Imagine yourself a regular Webvan customer searching Amazon for a gift. You set your "one click ordering" option to ship the product via your next scheduled Webvan delivery — with only a nominal shipping charge versus the normal one. With enough volume, Amazon could ship product into Webvan distribution centers with minimal marginal incremental cost for either party. And for high volume goods (such as best selling books currently sold by both companies), Webvan could pull the product from its own locally deployed stock. Together, Webvan and Amazon could be more efficient and as well as offer a better value to the consumer.

Business Model Evolution

In short, the predicted business model evolution for the last mile has begun — on Internet time. As Webvan CEO George Shaheen has asserted, only a few companies will earn the right to cross into the home. Although the last mile terrain remains treacherous, his proposed stock swap with HomeGrocer improves Webvan's odds of surviving an attack by a competitor fighting for the same right.

More importantly, though mergers will continue in Internet retailing, consolidation marks only the first step. Looking ahead, we see many exciting options as competitors shape and reshape business models to better serve the end consumer — and do so at a profit. ![]()

Reprint No. 00304

|

Authors

Tim Laseter, lasetert@darden.virginia.edu, serves on the operations faculty at the Darden Graduate School of Business at the University of Virginia. Previously he was a a vice president with Booz Allen Hamilton in McLean, Va. Mr/ Laseter has 15 years of experience in building organizational capabilities in sourcing, supply chain management, and operations strategy in a variety of industries. Pat Houston, houston_pat@bah.com Pat Houston, a Booz Allen Hamilton principal based in New York, focuses on driving organizational performance improvement through strategic and operational transformation. Anne Chung, chung_anne@bah.com Anne Chung, a principal in Booz Allen Hamilton’s Cleveland office, focuses on supply chain management and Internet-enabled operations. Silas Byrne, Byrne_Silas@bah.com Silas Byrne is an associate in Booz-Allen & Hamilton's New York office focusing on operational and organizational issues across a broad range of industries. Martha Turner, turner_martha@bah.com Martha Turner is a senior associate in Booz Allen Hamilton's New York office. She specializes in operations and supply chain management in a broad range of industries, with particular emphasis on e-business. Anand Devendran, devendran_anand@bah.com Anand Devendran is a consultant in Booz-Allen & Hamilton's New York office focusing on operational and growth strategies across a wide range of industries. |