Best Business Books 2002: Ethics

Enron and Other Moral Hazards

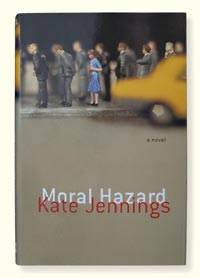

(originally published by Booz & Company) You have to understand,” says Cath, the heroine of Kate Jennings’s new novel of Wall Street excess, Moral Hazard (HarperCollins, Fourth Estate, 2002), “that Mike and I worked in the modern-day equivalent of the court of Louis XVI. All around us, impossible sums of money were heaped upon people who were no more deserving of it than any other kind of professional. Sure, they put in long hours in a Darwinian environment, but the same could be said of New York City public school teachers.”

You have to understand,” says Cath, the heroine of Kate Jennings’s new novel of Wall Street excess, Moral Hazard (HarperCollins, Fourth Estate, 2002), “that Mike and I worked in the modern-day equivalent of the court of Louis XVI. All around us, impossible sums of money were heaped upon people who were no more deserving of it than any other kind of professional. Sure, they put in long hours in a Darwinian environment, but the same could be said of New York City public school teachers.”

In this semi-autobiographical novel set in the 1990s, Cath, a feminist writer, finds herself forced into the epicenter of macho business culture when she accepts a job as a speechwriter for a big New York investment bank in order to pay for medical care for her husband, Bailey, who is suffering from Alzheimer’s disease.

Cath not only confronts her own moral dilemmas in working within a culture that is utterly alien to her personal values, she observes firsthand how the tenuous links between capitalism and ethical behavior sometimes snap under the pressure to make more and more money fast.

Through much of the 1990s, companies talked plenty about good governance and corporate social responsibility. Hanny, Cath’s boss, sees himself as the repository of the firm’s values, or “touchstones,” because “the apex of his career had been to give voice to them.” The values — words such as “respect” and “integrity” — appear “engraved on brass plates attached to walls, chiseled into marble floors, pressed into Lucite paperweights.” Gradually, Cath realizes how many lawyers are employed to defend the firm against charges resulting from lapses in these ubiquitously displayed values. Her boss tries to explain, “The touchstones are aspirational. In any company, there are peaks and there are troughs. It’s our job to describe the peaks.”

But how do we get rid of the troughs? It is hard not to conclude from Kate Jennings’s work of fiction, along with a new crop of business books examining the latest corporate scandals, excesses of the dot-com boom, and the struggle to preserve a moral balance in a moneyed world, that the relentless drive for a quick buck was largely responsible for the lapses and hubris of the 1990s — and for today’s dour business conditions. For all the talk about wealth creation for the many and the long term, what financial markets mainly care about is extracting as much as possible, as quickly as possible, for today’s shareholders. No wonder corporate bosses, faced with such pressures, give way to impatience and poor ethical judgment. In the current climate of censure and contrition, these books are valuable reminders of the ethical fragility of the capitalist system, so often invisible when times are good.

Boom Times

So did the hot years of the 1990s, like the reign of Louis XVI, really presage bloody revolution? Or is this one of the brief bouts of self-doubt that so often accompany economic downturns?

Look along the business bookshelves, and there are early signs that some authors have spotted a new bandwagon and are leaping aboard. Corporate adulation is out; repentance and rebuke are in.

With How Companies Lie: Why Enron Is Just the Tip of the Iceberg (Crown Business, 2002), A. Larry Elliott and Richard J. Schroth certainly have the title of the moment. Their book, finished in January 2002 and on the shelves in July, has that Methodist-preacher tone that President George Bush adopted in his speech to American business leaders in July, and which chimes with the times. “The financial manipulations that have emerged over the years are no longer tolerable,” the authors thunder. “Indeed, the damage caused by trading manipulations and accounting fraud … could be the seeds of serious calamity in the future.”

With How Companies Lie: Why Enron Is Just the Tip of the Iceberg (Crown Business, 2002), A. Larry Elliott and Richard J. Schroth certainly have the title of the moment. Their book, finished in January 2002 and on the shelves in July, has that Methodist-preacher tone that President George Bush adopted in his speech to American business leaders in July, and which chimes with the times. “The financial manipulations that have emerged over the years are no longer tolerable,” the authors thunder. “Indeed, the damage caused by trading manipulations and accounting fraud … could be the seeds of serious calamity in the future.”

Elliott and Schroth set out to tell you how companies befuddled investors, and why they got away with it. Their book is fun to read, although it shows the effects of writing in haste (it is a sort of tut-tutting amalgam of corporate naughtiness, flung together without much coherent structure or analysis). But it tells the target readers (investors and executives) what signs of trouble to look for in a company. These include lots of insider trading, projections about market potential that run counter to market research, and the abrupt resignation of senior executives. Ultimately, the authors write, good governance “largely depends on the integrity of the management team and the business culture they create and lead.”

The trouble is, in the atmosphere of a market bubble, it takes huge self-confidence to resist the pressure to stretch not just targets, but the truth, too. “Business lies begin innocuously,” Elliott and Schroth point out. “Cranberry juice contains only a fraction of real cranberries; blueberry cereal has no real blueberries.” They go on, “Business plans of new ventures are … based on the dreams of business planners more than market reality. Sales forecasts inevitably have elements of guesswork. And, when companies miss their earnings targets, impatient markets wreak prompt and terrible revenge.”

How true this was for the dot-com Value America, whose sorry tale is engagingly told by J. David Kuo in Dot.bomb: My Days and Nights at an Internet Goliath (Little, Brown and Company, 2001). Kuo, who lived through the rise and fall of Value America as its corporate communications officer, gives a witty and wide-eyed account of life in a failing dot-com, using a sharp instinct for telling details.

Value America, a onetime corporate dreamboat, was supposed to become the Wal-Mart of the Internet — indeed, the Microsoft of e-commerce. The face that smiles engagingly from the book wrapper is far too unwrinkled to have had any premonition of catastrophe as the company sailed through a $130 million initial public offering, its stock soaring to a market capitalization that was twice that of the strong books business of Borders, and then proceeded to burn its way through $12 million a month.

In the heady environment that Kuo so vividly describes, where even the call girls desert Hollywood for Silicon Valley and insist on payment in stock options, it is easy enough to see how integrity could get lost. Kuo joined the company after the stock price began to slide, only to discover that the job of the corporate communications offices was to get the stock price back up: “I was Value America’s Viagra.” What, in a sentence, described the company?, David Kuo asked CEO Craig Winn, the company’s creator. “There is no way to relate the revolutionary story of Value America in just one sentence,” replied Winn. “We are the marketplace for a new millennium.”

Kuo recalls how he felt at that moment: “All my internal voices sang in harmony, ‘Run away!’ It was a virtual symphony of fear.” But he didn’t: Instead, he stayed on to see, in the closing hours of 1999, the biggest Internet layoff on record as the company became the world’s first dot-bomb. Finally, in August 2000, the company went bust, as did hundreds of others that year.

Kuo’s book is as good an account as you’ll get of why people become carried away in a boom. Kate Jennings’s novel raises a broader question — whether the whole capitalist system is rotten and needs to be replaced by something better. Her (fairly) imaginary Wall Street investment bank, Niedecker Benecke, brings us back to the soaring and swooping era of the derivatives frenzy, the hedge fund debacle, the Asian markets crisis, and the default of Russia.

Jennings writes with charm, and gives a taste of the discomfort of being an ordinary, intelligent woman on Wall Street, where “women were about as welcome as fleas in a sleeping bag.” That alone gives her novel interest, and it is coupled with the fact that she speaks from experience: Jennings has done time as a speechwriter on Wall Street.

Her observations about the selfish and deceptive faces of capitalism are most telling when she writes about the gulf between what the company thought it believed in and the way it behaved. There is, for instance, a memorable passage in which, after Russia’s default, a banker breaks the corporate code of platitudes by demanding to know, at an in-house meeting to rally the troops, “Why was so much of our capital invested in a country that has never had a market economy … a country run by gangsters?” The chief executive responds, “It’s a risky world. Always has been, always will be.”

Jennings also neatly catches the tone of grandiose pseudo-altruism that so often pervaded corporate presentation in that era. The company launches a new advertising campaign under the slogan “Niedecker Benecke. Building the Globe. Building Tomorrow.” The head of corporate public relations outlines Niedecker’s plans to finance schools, hospitals, power plants, highways, and railroads — and to play its part in making every nation competitive. “Now, what were the take-aways from our discussion?” he asks patronizingly. “Niedecker is serving humanity, sir,” replies the heroine with ingratiating irony. “At its beck and call.”

However, Jennings’s most memorable and moving passages are not about capitalism and corporate ethics. They describe the wreckage of Cath’s husband, Bailey, by Alzheimer’s. Here, her prose comes alive. Back at the bank, she never really makes her criticism of corporate life bite hard, as Tom Wolfe did with his “Masters of the Universe” in Bonfire of the Vanities (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1987), or in the way that Anthony Trollope did in his magisterial novel of corporate greed and business failure, The Way We Live Now (Chapman and Hall, 1875). Both these writers, whose books are worth turning to again today, understood perfectly the male gender’s peculiar blend of arrogance, stupidity, and greed.

Perils of Myopia

Larry Elliott and Richard Schroth’s analysis, David Kuo’s memoir, and Kate Jennings’s fiction all in their different ways show the perils of the short-term approach to business that puts almost unbearable pressures on corporate managers. Conditions change in unpredictable ways, and even when times are good, development of new markets and new products is long and slow. Wall Street may want results in weeks, yet most companies take months, many quarters, or years to change.

Chuck Martin’s Managing for the Short Term: The New Rules for Running a Business in a Day-to-Day World (Doubleday, 2002) also analyzes the clash between short- and long-term timetables. Martin, who runs an executive think tank called the Net Future Institute, is in the rather old-fashioned business of discovering new rules for corporate survival — in his case, for managing within shorter time frames.

His is the only one of the five books reviewed here that has an instructional tone. (How-to-do-it books poured off the presses during the boom years; now, business gurus generally distance themselves a little more.)

Martin has talked, as authors of such books tend to do, with myriad bosses to discover how they see the world. The long term, it seems, is somewhere between two and five years; the short term, the quarter or the year. For some, such terms are mutable. “I am a sales VP,” said one of Martin’s interviewees. “I see life in 90-day increments. My joke is that strategic planning for me is where I am going to have dinner tonight.”

According to Martin, short-term management seems to require some fairly commonsensical principles: Quantify whatever you can, in order to set goals and align objectives; move forward in incremental steps that deliver results progressively; and make sure everyone in the company knows what the management is trying to do. All well and good. But a tiny note of alarm should creep in halfway through the book, when he lists which corporate departments present his executive interviewees with the greatest impediment to “change” (disturbingly, he fails to define precisely what he means by change). Fifteen percent of them pointed to the legal department; another 23 percent said finance. But sometimes, thwarting injudicious change is exactly what the legal and finance departments ought to do. Indeed, it seems neither department has done enough thwarting in some companies.

All too often in the past year, the chief financial officer has emerged as the boss’s accessory in massaging earnings or creating special off-balance-sheet hiding places for losses. At Xerox and Global Crossing, WorldCom and Enron, far from advocating intelligent management reforms, the CFO has notably failed to deter the sort of “short-termist” attitudes and actions that cheat investors and destroy wealth. Martin’s advice on making managers more effective and efficient is sensible enough, but it would have been much more reassuring in a book appearing at this time to see a chapter on the dangers of the short-term management approach.

Making Capitalism Work

In the aftermath of Enron, many people wonder whether there are ways to make sure that executives stay honest in the future, given all the pressures they face to stretch and bend the rules. The introduction of yet more corporate rules is unlikely to achieve very much. But there are some interesting suggestions for ways to reduce the short-term focus that makes life difficult for so many bosses.

For instance, Elliott and Schroth propose getting rid of 90-day reporting and replacing it with a “semiannual comprehensive review and report of audit.” The relentless reporting cycle currently forces executives to manage their stock first and their business second. “They don’t have the time to do both,” the authors write. Well put. The authors also call for more independent boards and more active communication between directors and investors. They want consideration of a provision that would allow directors to reject a takeover that is in the interests of shareholders but not of other stakeholders such as employees and host communities. (In the U.S., legislation passed by Congress in July 2002 to crack down on corporate abuses and increase shareholder protection begins to address some of these ideas.)

All this is radical stuff. Still, we live in radical times, when the only American president ever to have earned an MBA denounces executives for “breaching trust and abusing power,” accuses them of “cooking the books, shading the truth, and breaking our laws,” and demands “a new ethic of personal responsibility in the business community.”

The scandals at American companies have been particularly egregious, but capitalism has stumbled in Europe too. Any doubters should follow the tale of Asea Brown Boveri, the Swiss–Swedish engineering group that was once held up as a model of good governance and is now dealing with fraud affecting its results for 1999 and 2000. However, European authors sometimes seem more comfortable asking awkward questions about the basic morality of capitalism than American authors. That is certainly true of Charles Handy, a distinguished British observer of corporate life, and the only non-American writer represented in this selection.

Handy is no anti-American: Indeed, there are many aspects of American capitalism that he relishes. In his latest thoughtful and insightful book, The Elephant and the Flea: Reflections of a Reluctant Capitalist (Harvard Business School Press, 2002), he argues, “The idea that the future can and should be better than the past is one of the most invigorating aspects of American culture.” And he adds, “The envy that can be corrosive in other capitalist societies seems in America to fuel ambition and hope.” But he is realistic about the aspects of capitalism he does not relish. It is, he points out, “the only game in town. Even if we wanted to, there is no way to stop it.”

But that is not enough, Handy says. Capitalism needs to work for many more people than it does today. The benefits of capitalism are spread among perhaps 2 billion of the world’s 6 billion people. If capitalism does not succeed in the developing world, then the poor will leave: Migration is already, he says, “set to be the major issue of this century.” For all our sakes, we must find ways to make capitalism work everywhere.

That may require a different variant — or several different variants.

If we give too much priority to maximizing wealth creation, we may again forget the reasons we wanted wealth in the first place. As Charles Handy observes, “Capitalism knows all about the means of wealth creation but is unclear about the ends, who or what that wealth should be for. That may yet be its downfall.” To be sure, it is the get-rich-quick fever of the past decade’s wealth creation that has brought down so many of today’s companies and undermined faith in the financial system. Raw greed is not a stable foundation for a society to build on.

Do capitalists care? Jennings is a pessimist, likening bankers’ ability to forget the lessons of past mishaps to a form of professional Alzheimer’s disease. Larry Elliott and Richard Schroth are equally glum: “The most probable outcome of this financial chaos will be the traditional activity of ‘study, wait, delay, and forget.’ Those in political and business circles most responsible for the ‘Enrons’ of our time are the ones who do not want change.” And to tell the sad truth, public opinion polls give comfort to the foot-draggers. A recent poll found that American business leaders were even less trusted than Catholic cardinals.

In the end, neither reminders nor prescriptions will solve the problems. It will take capitalism to reform capitalists. If the markets begin to favor companies that struggle to put honesty before fudge, if they distrust mergers and reward transparency, if they prefer good management to earnings management, then change will occur. Only investors have the power to make good governance rewarding — and only if it is rewarding will companies adopt it as a matter of course. ![]()

Reprint No. 02407

| Authors

Frances Cairncross, FrancesCairncross@economist.com Frances Cairncross is management editor at The Economist. Her most recent books, The Death of Distance: How the Communications Revolution Is Changing Our Lives (Harvard Business School Press, 2001) and The Company of the Future: How the Communications Revolution is Changing Management (Harvard Business School Press, 2002), examine, respectively, the economic and social effects of the global communications revolution, and the ways in which the Internet affects how companies operate and are managed. |