A CEO guide to today’s value creation ecosystem

The drivers of enterprise value extend beyond financial productivity — and as disruption intensifies, businesses must adapt to avoid value destruction.

A version of this article appeared in the Summer 2021 issue of strategy+business.

In the blink of an eye, COVID-19 disrupted the business environment and illuminated a profound, sometimes overlooked truth: that to create, protect, and sustain enterprise value, executives must consider a set of stakeholders much wider and more diverse than just shareholders.

Disruption and the breadth of the value creation ecosystem are, in fact, connected. In recent months, as supply chains have faltered, channels to market have evolved, and companies’ roles in caring for their customers and employees have been magnified, it’s become clear that the pursuit of financial productivity and profitable growth, long the core of traditional value creation models, is inadequate on its own. Companies must do more. Those looking to create enterprise value — a term we’ve chosen intentionally over shareholder value — must also cultivate resilience and contribute to the well-being of society, both now and in the future.

Even before the pandemic, the Business Roundtable’s August 2019 “Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation” — signed by almost 200 CEOs to express their commitment to serve not just corporate shareholders but all stakeholders — reflected an evolution in the way leaders were thinking about how to run their companies. For many years, creating and protecting enterprise value has meant managing a diverse ecosystem of financial, societal, environmental, and other factors. That reality hasn’t changed. What has changed is that the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the fragility of relationships throughout the ecosystem and the dynamism of change within it. It’s also amplified and accelerated the connections among financial productivity, resilience, and society. And it’s accentuated the danger of ignoring any of these parts of the value creation ecosystem. The pandemic has exposed leaders’ blind spots and put many companies on the defensive.

In all these ways, COVID-19’s impact has been acute. But other long-brewing disruptions — including the quickening pace of technological development and growing concerns among investors and consumers about issues such as climate change, racial inequality, income disparities, and political polarization — have the same implications. As these forces escalate, some will have a substantial and rapid effect on enterprise value.

Now is the time for leaders to analyze these varying impacts and turn disruption into an offensive weapon by reinventing their planning processes, reframing their strategies, and revising their ways of working. And in taking these steps — which might include creating new supply chains, new products, new people policies, or even new standards of transparency in decision-making — organizations need to recognize that disruption and value creation are inextricably linked, and although disruption is continually posing risks to corporate value, it’s also presenting new opportunities. Some of the levers businesses can pull will help them win in their industry, and others will help them win in society. Crucially, some will do both. In this article, we’ll describe what we think are the most important actions for creating long-term enterprise value in today’s value creation ecosystem.

Understanding the current value challenge

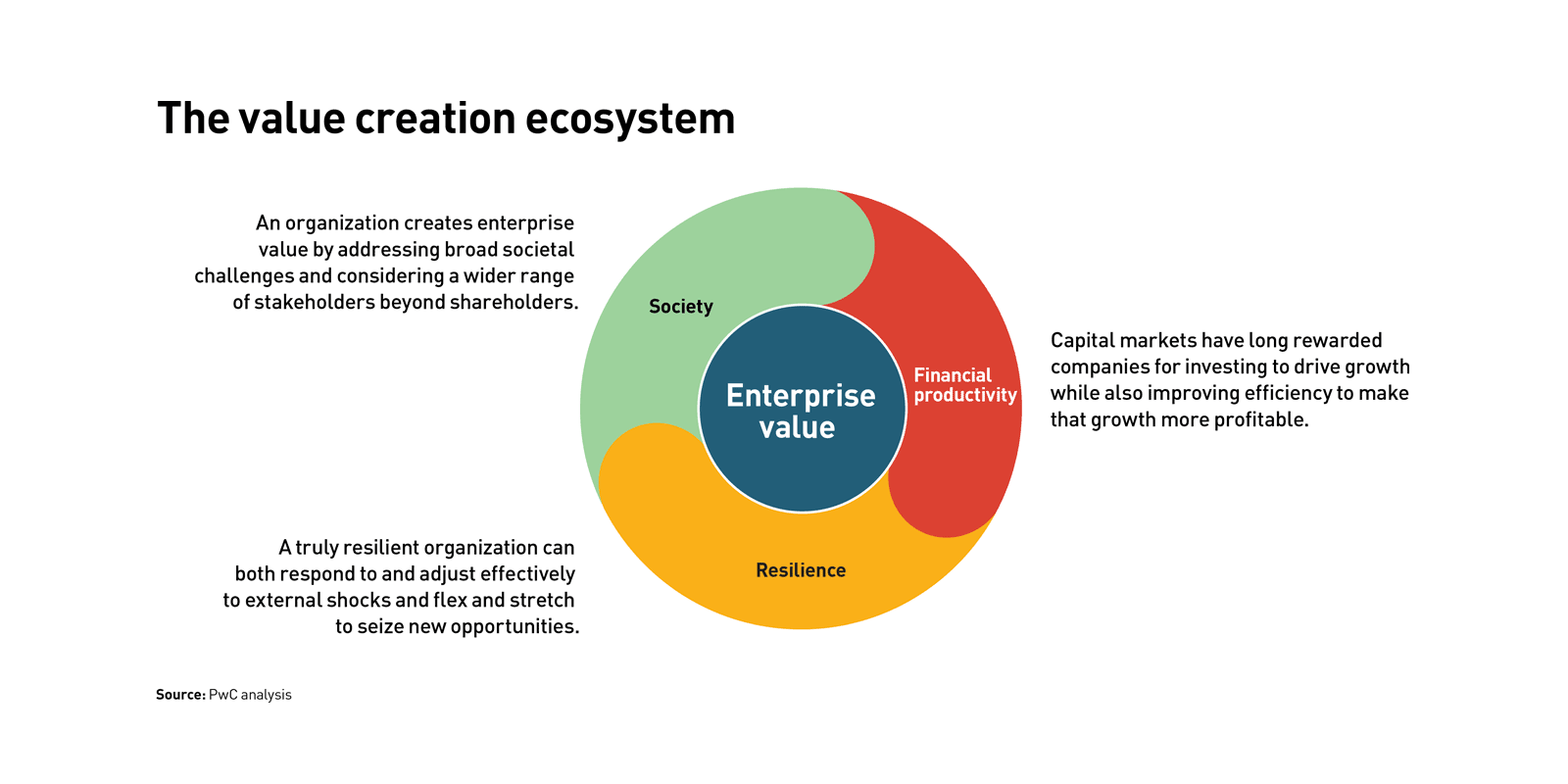

Companies setting out to create and grow enterprise value in today’s value creation ecosystem first need to fully understand its topography — and the trade-offs, tensions, and balancing acts that are inherent within it. The ecosystem consists of three interrelated components:

• Financial productivity. Capital markets have long rewarded companies for investing to drive growth while also improving efficiency to make that growth more profitable. As a result, companies have always had to carefully balance spending money and saving money, with the added consideration that investing for growth is a long-term enabler in building resilient assets. Organizations have responded to the capital markets’ focus on financial outcomes by becoming very good at measuring and communicating their financial productivity, focusing much more on that than on nonfinancial aspects of their performance and impacts.

• Resilience. A truly resilient organization can both respond to and adjust effectively to external shocks (that is, it has defensive adaptability) and flex and stretch to seize new opportunities (offensive agility). COVID-19 has amplified the value of being resilient in areas such as supply chain and digital platforms. And the increased need for resilience in these areas has captured the attention of capital markets — in turn creating new imperatives for leaders seeking to build enterprise value.

• Society. An organization also creates enterprise value by addressing broad societal challenges and by considering in its decision-making a wider range of stakeholders beyond shareholders. This approach can, for instance, avoid the value destruction that can result from climate risk or boost value by attracting and retaining more talented, engaged, and productive employees via diversity and inclusion programs. And actually, the interests of shareholders and other stakeholders are, in many cases, converging. Shareholders’ perspective on value is becoming more long-term and more holistic. In recent months, the interdependencies and widening inequalities highlighted by COVID-19 have further intensified the pressure on companies to deliver, measure, and report on longer-term value creation for society.

For some years, the balance among these three sources of enterprise value has been shifting. Long before COVID-19, companies whose strategies and assets were over-indexed on efficiency were struggling. For these businesses, a focus on near-term returns often has meant trading off the long term — an imbalance that the digital era has made more obvious. Reconfiguring to compete successfully in the 21st century requires a business to flex and upgrade critical capabilities such as strategic direction-setting, resource allocation processes, and governance, which together enable the deployment and recalibration of operating assets. Stretching these same capabilities is also crucial for leaders if they are to make their companies more resilient and more purposeful contributors to society, thereby creating, or at least avoiding the destruction of, enterprise value.

Getting on the right — or wrong — side of COVID-19 trade-offs

The pandemic has thrown the trade-offs among financial productivity, resilience, and society into sharp relief. Those on the right side of the trade-offs include the companies that responded quickly to the disruption of business as usual — perhaps by repurposing their production facilities and supply chains to maintain some level of activity while also generating societal value.

Organizations need to recognize that disruption and value creation are inextricably linked, and although disruption is continually posing risks to corporate value, it’s also presenting opportunities.

Consider the France-based luxury goods maker LVMH. In March 2020, the company retooled three of its high-end perfume and cosmetic manufacturing facilities to produce hand sanitizer, which it distributed to the French hospital system at no charge. It then helped address France’s surgical mask shortage, using its global distribution network to secure an order with a Chinese industrial supplier. All this took place during a calendar year when LVMH’s market capitalization rose by about one-third. There are many similar examples of companies redirecting their resources to help address the pandemic. In Japan, electronics giant Sharp repurposed the clean rooms in a TV factory to make 150,000 surgical masks a day, which grew to 600,000 as the company expanded its production capacity. In Spain, the “fast fashion” group Inditex, owner of Zara, made its logistics and procurement capabilities available to help buy and transport health equipment.

Automakers also rallied to the cause. Ford’s contribution included using its 3D-printing capabilities to make face shields and its manufacturing expertise to help Thermo Fisher Scientific ramp up production of COVID-19 testing kits. And General Motors announced plans to start making ventilators at a facility in Indiana, even before being directed to do so by the federal government under the U.S. Defense Production Act. Through such actions with broader stakeholders during the pandemic, these companies enhanced their brand and reputation — and hence their enterprise value.

However, COVID-19 has also presented pitfalls. In the U.K., for example, several of the country’s largest supermarkets initially accepted the government’s offer of relief on property taxes despite being allowed to stay open during lockdowns. A storm of criticism on social media and from politicians was heightened when some of those companies continued to pay dividends to shareholders. In December 2020, five of the biggest U.K. supermarkets said they would repay a total of more than US$2.3 billion in government relief.

The pandemic isn’t the only reason companies have found themselves struggling recently in the value ecosystem. In July 2020, advertisers pulled millions of dollars from a major social media network to pressure it to do more to tackle harmful content such as hate speech. Again, the message was clear: If a company fails to act with purpose, it risks destroying enterprise value.

Five priorities for reinvigorating your value creation strategy

We’ve identified five actions that we believe business leaders and their organizations can take to help shape and execute effective strategies in the context of the broader value creation ecosystem.

1. Apply “visionary valuation” — along with ongoing measurement and correction

If a strategy is disruptive — take Toyota’s launch of the Prius two decades ago, as a bridge to electric vehicles, or Apple’s creation of the tablet market with the iPad — it can be difficult or even impossible to measure its value creation potential with any certainty prior to execution. In fact, any attempt could end up blocking innovation and, ultimately, value. Instead, leaders should look to achieve a “visionary valuation” by clarifying the forms of value they’re trying to create, understanding how commitment to those types of value will drive enterprise value, and developing a set of key performance indicators (KPIs) to track value creation across this broader ecosystem. Then, while executing the strategy, the business should measure the outcomes continually, using the results to recalibrate, course-correct, or even replace the strategy, and to report, listen, and respond to stakeholders in a feedback loop.

Organizations need to do these things against a global backdrop in which both the destruction and the creation of value, including value-associated issues such as climate change and social upheaval, are accelerating. In such an environment, the only way to communicate effectively with stakeholders is by translating critical corporate priorities through a value lens and representing the effects of strategic decisions and subsequent actions in a unified value framework. Such a framework will reinforce linkages between a company’s purpose and its strategy; between its strategic priorities and transparent reporting of all its results, including nonfinancial ones; and between its agenda for corporate transformation and societal renewal. It also will help communicate interconnections within the value creation ecosystem and clarify enterprise value drivers that historically might not have made their way into a calculation of net present value.

Unilever puts sustainability at the heart of its strategy. An instance of a business making these linkages explicit arose in December 2020, when global consumer products giant Unilever announced it would put its climate transition action plan before shareholders for approval, reportedly becoming the first major global company to take such a step. The move strongly underlined the convergence of the shareholder and wider stakeholder agendas. Unilever CEO Alan Jope commented, “We have a wide-ranging and ambitious set of climate commitments — but we know they are only as good as our delivery against them. That’s why we will be sharing more detail with our shareholders, who are increasingly wanting to understand more about our strategy and plans.”

In measuring and reporting on its progress on reducing carbon emissions, Unilever says it will continue to take an iterative and transparent approach, updating its plans on a rolling basis in response to outcomes and being clear about challenges across its value chain.

This approach echoes the company’s strategy over the past decade with its Sustainable Living Plan. Launched in 2010, the plan targeted three objectives, each aligned with the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals: First, improve health and well-being for more than 1 billion people by 2020; second, halve its environmental footprint by 2030; and third, enhance the livelihood of millions of people by 2020. Marking 10 years of the plan in May 2020, Jope stressed the iterative nature of the company’s actions in response to its KPIs: “As the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan journey concludes, we will take everything we’ve learned and build on it. We will do more of what has worked well, we will correct what has not, and we will set ourselves new challenges.”

By aligning its purpose with that of its customers and consumers, Unilever strengthens its reputation and brand value — and avoids alienating its customer base and destroying value.

Like several other companies, Unilever also undertook a high-level assessment of the potential material impacts on its business arising from the 2- and 4-degree Celsius global warming scenarios for 2030. Its analysis confirmed that both scenarios presented financial risks to its business, including rising costs of raw materials and packaging in a 2-degree rise and chronic water stress and extreme weather in a 4-degree rise. For Unilever, the assessment confirmed the importance of understanding the critical business dependencies of climate change and having plans in place to mitigate risks and prepare for the operating environment of the future.

2. Think like a disruptor

To rethink strategy in the face of disruption, businesses in any industry can ask: If we were coming into this marketplace today as a new entrant, unburdened by legacy infrastructure and assets, what strategy would we adopt? This blank-slate mindset enables leaders to anticipate new competitive threats and opportunities and potentially formulate, evaluate, and fine-tune a strategy that could turn them into actual, not hypothetical, disruptors.

Organizations that have fully deployed and executed a blank-slate strategy are few and far between. But among those that have, several have succeeded in creating sustainable new operating models that have significantly boosted enterprise value — and some are extending that value creation far across their ecosystem. We’d suggest, in fact, that the gathering force of the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) imperative will create enormous opportunities for disruption and self-disruption, just as the digital revolution did.

Netflix and Qantas self-disrupt. Take Netflix, which has disrupted its industry twice and itself once: first by launching a DVD mail service against incumbents such as Blockbuster and then by switching to streaming in 2007 and production of in-home entertainment in 2012. The second strategy, in particular, delivered. In the third quarter of 2010, Netflix’s market value was $8.75 billion. A decade later, it was $233 billion.

Another prominent example of blank-slate self-disruption was the launch of the low-cost airline Jetstar in 2003 by the Australian incumbent Qantas, which faced fierce competition in the early 2000s from an Australia-based low-cost carrier. A review of previous low-cost carrier launches by other incumbents that had failed quickly revealed the underlying problem: The legacy carriers were trying to avoid disturbing their core. Qantas’s board decided not to make the same mistake. It set about building Jetstar as a completely new low-cost carrier that would be as separate and independent as possible from Qantas’s core business and even compete with it in some ways. This meant recruiting Jetstar’s management externally; basing the company in Melbourne rather than Sydney; having no direct check-through of baggage between airlines, no shared terminals, and no access to the Qantas loyalty or reservation systems; and often using different — lower-cost — airports.

Crucially, Qantas accepted that the parent business would lose some revenues to its new offspring. Point-to-point routes that were less profitable for Qantas were reallocated to Jetstar. The Sydney to Melbourne trip — one of the world’s busiest domestic routes — was shared, with Jetstar’s flights timed to suit cost-sensitive leisure travelers and Qantas’s scheduled for the less cost-conscious business market.

The outcome? Over 18 years, Jetstar has proven to be a highly successful airline that has taken market share profitably from Qantas and the competition. Qantas itself flies fewer routes than before Jetstar came along, but those routes are more profitable. By thinking like a disruptor, Qantas tapped into a massive low-cost market that might otherwise have gone elsewhere. It was a brave decision by Qantas’s leaders — and a smart, value-adding one for the group’s future.

Private equity player buys dirty, sells clean, and extends the value creation ecosystem. Thinking like an ESG disruptor can be pivotal in deriving value from M&A. Consider a bid that’s currently underway from a private equity investor for a listed financial institution facing significant regulatory and reputational issues. The target has struggled for some years. First, it couldn’t change fast enough in response to shifts in the market for its financial products. For example, it was aware of changes to the regulation of advice, but its internal controls were not strong enough to adequately monitor compliance with the regulation, triggering a series of private litigations. Then, its group executive and board misread the sentiment of leadership and a shift in community expectations, and this issue bubbled up into the public domain, affecting the company’s reputation. The resulting slide in the company’s valuation attracted the attention of private equity investors, one of whom tabled a takeover offer with a control premium effectively funded by removing the overhang of anticipated future regulatory actions. It’s a strategy sometimes characterized as “buy dirty, sell clean.”

The bid is ongoing. For the potential acquirer, the key questions are what issues it can solve within the targeted acquisition to rebuild enterprise value, and in what time frame. Its four-step strategy is designed to harness disruption by starting from a blank slate:

- First, clarify the value proposition for the financial advice business.

- Second, address the regulatory compliance issues, thus helping to rebuild trust and remedy the 20 percent discount against fundamental value created by the reputational concerns.

- Third, tackle operational complexity to reduce the cost base.

- Fourth, divest some parts of the group’s portfolio to realize additional value.

This strategy is aimed at “cleaning up” the core of the business and making it fit to be run profitably with increasing enterprise value — powered by societal impacts, reputation, and trust in the broad value creation ecosystem.

3. Prioritize ruthlessly

Strategic shifts don’t become real until a business reallocates the capital, talent, and other resources needed to put them into effect. A variety of forces, sometimes including the personal interests of an organization’s leaders, conspire to create inertia. Yet amid today’s relentless disruption and evolving perceptions of value, it’s vital to be prepared to act radically and quickly in allocating resources where they’re most needed — or the strategy will fail. Although the shock of COVID-19 has triggered an acceleration of change that makes more actions possible, it has also broadened the range of potential priorities that leaders must consider when deciding where to focus. The effect is that it’s more important than ever to be able to prioritize, and to identify and act on the most effective value drivers in the value creation ecosystem.

Aerospace and defense company links ESG to enterprise and shareholder value. Across all industries, ESG initiatives have become essential in building engagement and trust with stakeholders and in boosting enterprise value. An aerospace and defense client we work with has long recognized the need to place a higher priority on ESG considerations and associated value drivers. But to make a compelling case for investing in programs related to ESG and to build buy-in among a broad set of stakeholders — including its own board, the investor community, and its suppliers — it needed to tie ESG initiatives back to measurable effects on corporate value.

To do this, the client identified and tracked the value impact of its ESG programs all the way through to intrinsic enterprise value and ultimately value for shareholders. The resulting long-term view of intrinsic value looks well beyond earnings per share. The company started by developing “impact pathways,” identifying the ways in which business issues intersected with ESG issues. It then broke down the value chain to pinpoint where those intersections drove the greatest value or risk. The next step was to ensure that the company had a sufficiently robust definition of value to support decision-making. Ongoing actions in the program include selecting key ESG initiatives, quantifying their effect on value across the impact pathways, and communicating the results to various stakeholder groups.

Major energy company optimizes resource allocation through a unified value metric. When a company is looking to reframe its existing strategy and resource allocation process to address the broad value ecosystem, the ideal approach to prioritization might be to take it to the next stage: optimization. At root, prioritization involves ranking different metrics — such as cost, revenue, and environmental impacts — and deciding to fund activities that surpass a particular line. Optimization is more sophisticated, involving assessment of a dynamic combination of projects or investments using a comprehensive set of considerations, constraints, and resource levels. Recently, we worked with a major energy company as it optimized its approach in this way.

This work began with a deep consideration of the company’s values, business model, and strategy. The next task was to develop a new value framework — one that supplemented traditional financial measures with ESG levers, including impacts on the environment, communities, customers, regulators, employees’ health and safety, innovation, and operational and supply chain resilience. All these elements were combined into a single value metric that enabled the company to make resource allocation choices and assess trade-offs at the business portfolio level based on a broad view of value.

The company used a technique called multi-attribute utility analysis to achieve this outcome. Operating like a foreign currency translation, this technique involves taking each value driver and developing relevant KPIs for it. The KPIs are then scaled up, calibrated, and consolidated into a single value metric, enabling all potential investments or projects to be valued on an equal footing. Once all the company’s projects have been evaluated, leaders decide on the right trade-offs to make in the portfolio. This can be accomplished through an optimization model that assesses different levels of budget — together with dependencies and other resource constraints — over a multiyear horizon. Today, our client is applying the unified value framework across its business units and key functional areas, enabling it to prioritize using a broad view of value.

4. Execute at higher pace

Faced with multiple fast-moving disruptions, intensifying real-time scrutiny, and shifts among the various drivers of enterprise value, leaders no longer have the luxury of rolling out a strategy gradually. Executing at anything less than the highest possible speed brings the risk that events will overtake the rationale for the strategy. Faster businesses could also leapfrog slower-moving ones. In these cases, being first might be more important than having the perfect strategy from Day One, especially given opportunities for iteration and fine-tuning later, and buying capabilities might be preferable to taking time to build them. The need for speed is even greater in situations in which unforeseen disruption suddenly puts existing business models and revenues, and therefore enterprise value, under pressure, as has happened to many companies during the COVID-19 crisis.

Coty transforms at record speed to complete a sale amid the pandemic. In October 2019, Coty, one of the world’s leading perfume and cosmetics businesses, announced plans to divest its professional beauty division, which supplied premium shampoos and colorants to hair salons and polish to nail bars. In January 2020, Coty launched the sales process for that division, and the private equity firm KKR & Co. and a German cosmetics company were seen as the front-runners. But the week before the presentations to the potential bidders, much of the world went into lockdown. Overnight, sales to hair salons and nail bars fell by 80 to 90 percent.

Recognizing that speed and agility would be key, Coty sprang into action. The initial question was how long the lockdowns would last. But the focus soon turned to a longer-term issue: How would the business continue to thrive in a world where sustained social distancing meant salons would operate at only 50 to 60 percent of their previous capacity? Also, the division’s sales model had salespeople taking orders during salon visits — but many hairdressers and nail techs were no longer in a central location because many salons were shut down.

This sales channel, now highly fragmented, would have to be serviced in a different way, requiring a radical reconfiguration of the business. Within days, Coty developed an entirely new digital business and operating model — one under which the products would be promoted online, ordered by customers mostly via mobile, and delivered directly via a fast, optimized fulfillment process. Coty also quickly quantified the implications for profitability. Its rapid action minimized the pandemic’s impact on the valuation of the business.

In June 2020, KKR signed a purchase agreement for Coty’s professional beauty division, and the deal was completed in November. Coty sold a 60 percent stake in the Wella business in a deal putting Wella’s enterprise value at $4.3 billion. Since the sale, Coty has continued to gain strength: That same month, Coty announced improved first-quarter financial results, which CEO Sue Nabi said were “testament that a stronger, more focused, and more flexible Coty is emerging in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, and better prepared to face any future market disruptions.” This ability to rapidly overhaul value creation approaches is likely to be critically important in the decade ahead, as climate change and social inequalities challenge the status quo.

5. Be more attuned to your ecosystem

It’s vital to have the flexibility to adjust if conditions change, if the strategy isn’t delivering, or if current actions are destroying value. This means moving away from executing on fixed rails as in the old days, and accepting that the business’s strategy, plans, or behavior will have to change as new disruptions, risks, opportunities, and KPIs emerge. In the era of social media, this agility needs to be underpinned by the use of real-time monitoring tools, such as social listening, for continuously scanning and tracking consumer sentiment.

Consumer sports brand responds in an agile way to a social media firestorm. During the first months of the pandemic, a leading sports fashion brand decided to withhold rent payments on its shuttered retail premises. However, the company had considered only financial productivity levers rather than the whole value creation ecosystem. The announcement sparked an immediate and expanding firestorm on social media. Fortunately, the company’s leaders were alert to the damage to the company’s brand value and announced within a matter of days that it would pay its rents after all. The social media storm subsided, and consumers returned to holding a positive view of the business.

This sequence of events underlines several lessons for organizations navigating the value ecosystem. The clearest is that simply setting up a presence on social media and treating it as a one-way messaging channel is doomed to failure. Social media is a two-way medium; it’s crucial to listen to consumer sentiment in real time and respond just as fast. The episode also highlights the importance of considering value levers in a holistic and coordinated way. And it shows that consumers will turn against a brand if they feel it’s behaving contrary to its own societal purpose — but they are ready to forgive if they feel the brand has listened to their concerns and responded by doing the right thing. Companies that aren’t agile in managing and building seemingly intangible assets such as brand and reputation will face rising risks to value in the years to come.

Today, it’s vital for all leaders to be cognizant of the broad value creation ecosystem, given its profound implications for the creation or destruction of enterprise value. The opportunities for organizations that understand and manage all their value levers in a responsive and coordinated way are mirrored by deep pitfalls for those that fail to do so. The question we hope to have answered for you isn’t whether to set and execute your strategy to align with resiliency and societal value as well as financial productivity, but how. As we advance into the post-pandemic world, this will be perhaps the single biggest business challenge facing every CEO.

Author profiles:

- Helen Mallovy Hicks is the outgoing global valuation leader for PwC. She led a global task force to study the impact of ESG attributes on enterprise value and helped her clients make better decisions based on value. She is a partner in the deals practice of PwC Canada.

- Aaron Gilcreast is the incoming global valuation leader for PwC and oversees ESG initiatives in the U.S. firm’s deals business. He advises clients in value-based strategy, corporate finance, business modeling, and complex valuations used for hard-to-quantify value attributes. Based in Atlanta, he is a principal with PwC US.

- Hein Marais is the global value creation leader at PwC. He advises clients on how to create value through the buy and sell side of M&A. Based in London, he is a partner with PwC UK.

- Chris Manning is a leading practitioner with Strategy&, PwC’s strategy consulting business. He helps clients redefine their strategic positioning in the face of challenging or changing industry structures and dynamics. Currently based in the U.S., he is a partner with PwC Australia.