How conglomerates can do better in emerging markets

Despite investor skepticism about business conglomerates, in emerging markets they are well placed to improve returns. But they need a sharper focus and a better-defined strategic identity to guarantee future performance.

Conglomerates in the West are feeling distinctly unloved these days. Investors and business leaders have become increasingly skeptical toward them, unconvinced of the benefit of grouping a number of diverse businesses together under one corporate umbrella. In some markets, they are seen as lumbering, unfocused, and inefficient.

The result? Markets have applied a “conglomerate discount” to these businesses, valuing them below the sum of their parts. The removal last year of U.S. conglomerate General Electric from the Dow Jones Industrial Average is perhaps the most obvious example of this. Investors were already taking aim at conglomerates in Europe well over a decade ago, notably in the cases of Mannesmann and Preussag, two storied German conglomerate names that shed their long-standing industrial legacies to become focused businesses in a series of dramatic multibillion-euro deals in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Such skepticism may be well founded in developed economies such as the U.S. and Europe. In emerging markets, however, including India, Mexico, and Southeast Asia, the conglomerate is alive and well, and a number of factors are providing a supportive backdrop for this business model. Industry leaders such as India’s Aditya Birla Group, Mexico’s Alfa, Indonesia’s Salim Group, Ayala Corporation of the Philippines, and Vietnam’s Vingroup are good examples of such leading conglomerates.

Nation-building policies — such as the “Make in India” initiative launched by the Indian government in 2014 — and policies that tend to support homegrown industries are a key element of that supportive backdrop. Conglomerates have also benefited from governments’ inability to tackle large infrastructure challenges, stepping in with know-how and financing where governments can’t or won’t.

Even given this positive narrative, though, conglomerates in emerging economies can improve their performance by developing a much clearer identity.

Very often, the identity and focus of a conglomerate have emerged slowly and in piecemeal fashion; leaders frequently make decisions to invest in countries or markets without first building the capabilities needed to support those decisions.

To achieve the best returns, conglomerates must settle on what kind of conglomerate they want to be, and what they are capable of becoming. Once their identity is clear, conglomerates should build the capabilities they need to support that identity.

Strategy&, PwC’s strategy consulting business, recently carried out a study analyzing the operations and performance of more than 30 conglomerates. The research looked at the evolution of business groups across regions and the way the markets have viewed the attractiveness — or otherwise — of conglomerates as investments. Focusing on those regions where “conglomeration” still remains a viable strategy, the study identified five strategic models for conglomerates. Each offers a clear route to value creation and defines the actions that will drive the best performance.

What sets a conglomerate apart?

A conglomerate is a business group consisting of several distinct, sometimes unrelated businesses. For this study, a conglomerate needed to have a presence in at least three industry sectors that were not part of the same value chain (mining, metal fabrication, and metal products manufacturing would not count, for example, because they are part of the same value chain). In addition, the conglomerate’s business in at least two of the sectors had to account for more than a significant share of total sector revenue. Strategy& developed two metrics that help to show varying degrees of conglomeration in a country or region:

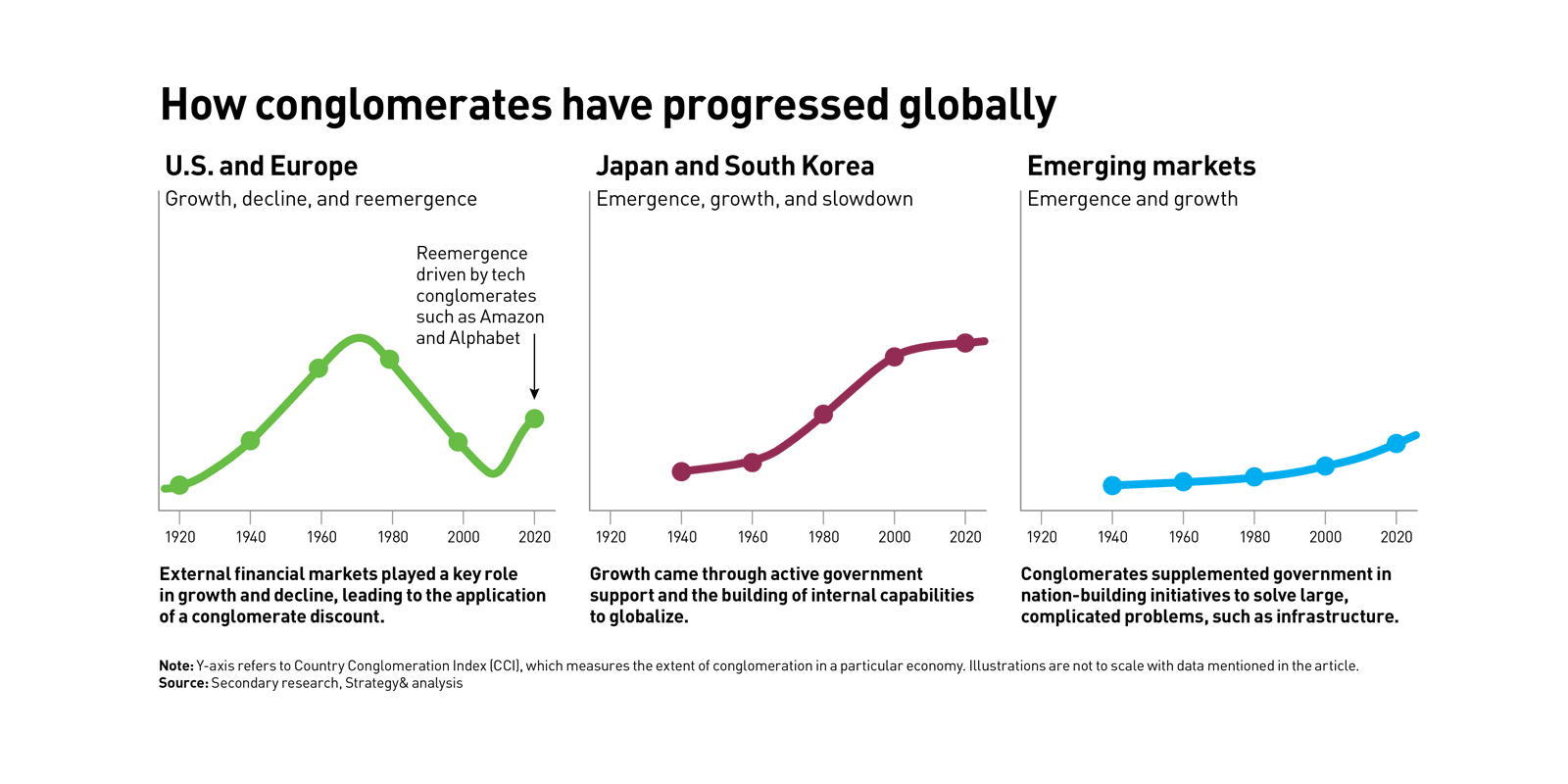

The Country Conglomeration Index (CCI) measures the extent of conglomeration in a particular economy, and simply shows the market capitalization of the top five conglomerates as a percentage of the total market capitalization of all listed companies on that country’s stock exchange.

The Country Conglomeration Quotient (CCQ) measures the degree of diversification within a conglomerate, defined by the number of sectors it operates in and the extent to which a sector occupies a significant share in the conglomerate’s overall portfolio.

Emerging market conglomerates are at an inflection point

Looking at three groupings (U.S. and Europe, Japan and South Korea, and emerging markets) through the lens of the CCI and CCQ (see “How conglomerates have progressed globally”), we can see that conglomerates in the U.S. and Europe have been through a complete cycle of emergence, growth, and decline (displaying a CCI of 3 to 8 percent) and are now in growth mode again as technology giants such as Amazon build diversified stables of businesses.

In South Korea and Japan, conglomerates including South Korea’s chaebol have grown significantly in the last 50 years and dominate the economy, with a current CCI of 50 percent.

In emerging markets, conglomerates are at an inflection point (with a current CCI of 15 to 25 percent), as the market dynamics around which they were built start to change in the following ways.

First, although government support for conglomerates is declining — meaning they are less directly supported at home — the protectionism sweeping much of the globe has provided a fresh rationale for building up diverse groups within one country.

Second, emerging markets have in recent years been buoyed by a rising middle class, and this is offering a new avenue for growth. Many conglomerates are taking advantage. That is particularly the case for conglomerates whose businesses may historically have been based on manufacturing and asset-heavy industries in which there is now a degree of global overcapacity.

Emerging markets have in recent years been buoyed by a rising middle class, and this is offering a new avenue for growth. Many conglomerates are taking advantage.

One relatively recent example of this second trend was a move in 2017 by India’s Reliance Industries oil group into telecommunications with the launch of Jio, a mobile voice and data service, which has grown rapidly as more and more Indian consumers have been able to afford mobile telecom products.

Yet emerging market conglomerates also face a number of challenges. The gradual opening up of home markets to foreign investors has created more competition. One notable instance affected India’s retail sector in 2018 when U.S.-based Walmart bought a US$16 billion stake in local e-commerce giant Flipkart.

Smaller companies are gaining greater access to capital, resulting in heightened competition. And workers have many more choices than they previously did, so it is becoming increasingly difficult for conglomerates to attract and retain world-class talent, especially at the entry level. Finally, technology disruption is bringing its own set of challenges in the form of displacement of business models.

These factors illustrate why it is now time for emerging market conglomerates to sharpen their focus and be clearer about their identity and business models.

What is the ideal emerging market conglomerate model?

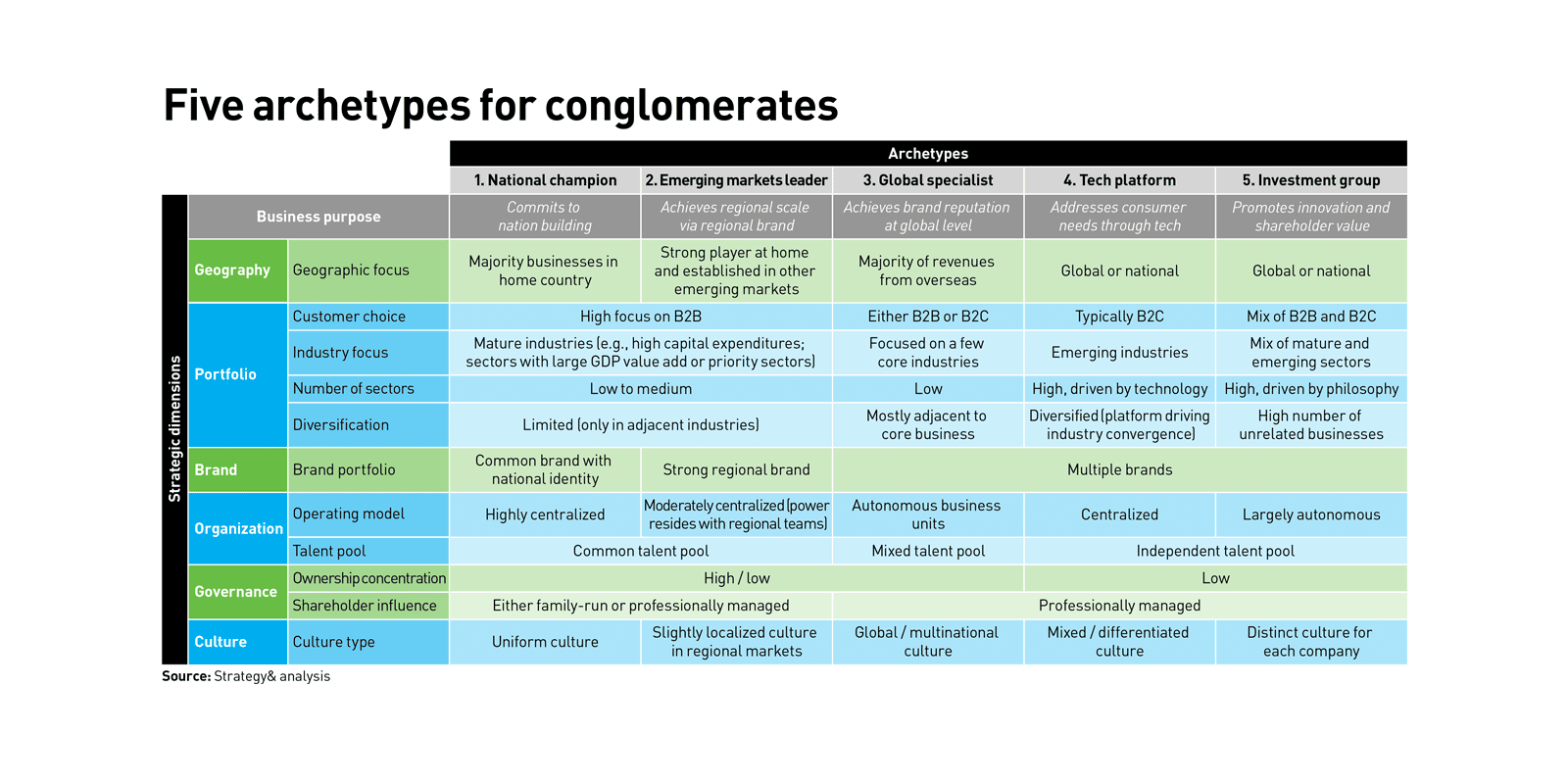

Leaders deciding on the best focus for their business should find the following five archetypes useful (see “Five archetypes for conglomerates”).

• A national champion is defined by a strong focus on its domestic market and by running B2B businesses, mostly in mature industries. The national champion is also typically present in a few adjacent sectors, so as to be able to cross-leverage capabilities. A common “parent brand” representing national identity develops a high degree of trust and loyalty among customers and employees. Decision making is generally centralized, and talent moves in a fluid way between the business units. A uniform cultural thread runs across all the businesses. Adani Group, an Indian conglomerate with operations in coal trading, port development, and power generation, has created a strong brand identity in B2B businesses and has significant involvement in national projects.

• In addition to being an established player in its home market, an emerging markets leader seeks to achieve regional scale and has a strong foothold in other emerging markets. Its focus is B2B businesses, mostly in mature industries, that are typically adjacent to one another. EM leaders have a moderately centralized operating model; power resides partly with regional teams. A common talent pool is leveraged across group companies and business segments. Culture is localized in order to address the requirements of each regional market. Larsen & Toubro, an Indian conglomerate specializing in heavy engineering, is one example and has expanded to the Middle East and Africa through strategic partnerships and joint ventures with local companies.

• A global specialist operates in multiple sectors in its home market, but its global approach is defined by a focus on one or two sectors. Most group revenues come from one sector. Typically, the business units run autonomously and the group tries to establish a global culture with a mixed talent pool. Alfa, a Mexican conglomerate, is a global specialist operating domestically in five unrelated sectors including packaging, IT services, and oil and gas exploration. But when it expanded overseas, it focused on two sectors (food and automotive parts) and now generates 59 percent of its revenue from outside Mexico.

• The tech platform archetype usually focuses on B2C businesses in emerging industries; tech platform conglomerates have a presence in multiple business segments using a common platform. Different brands are built to represent distinct identities for each business segment. Decision making is highly centralized. One example: Reliance Industries’ Jio is a digital platform that is used to provide a variety of services to a captive subscriber base in media and entertainment services, digital payments, and e-commerce.

• The investment group archetype operates in a large number of unrelated businesses (a mix of B2B and B2C) in mature as well as emerging industries. Decision making is highly decentralized; each group company functions as a stand-alone entity. The group companies do business under different brands with little or no relation to the holding group. Votorantim, a Brazilian conglomerate operating as an investment group, has created governance structures giving more autonomy to its group companies, and has modified brand names to reduce their association with the holding group.

A clearer identity leads to higher returns

Conglomerates in emerging markets should aim to gravitate toward one of the five archetypes. They can do this by building, developing, or buying new capabilities, as well as strengthening core capabilities and retrofitting obsolete capabilities to help them succeed in the next decade.

Greater coherence with archetype dimensions leads to significantly higher returns. Lack of clarity in the identity leads to “capability drift” and consequently a lower performance.

A national champion, for example, would need to focus on operational excellence in particular by cultivating strong project execution skills and strengthening regulatory influence to win in its markets. Adani Group, an Indian conglomerate, has achieved operational excellence by enhancing data-sharing and analytics across three business units: resources (coal mining), transportation (ports, logistics, shipping, and rail), and energy (renewable power, thermal power, and power transmission). It has also built a generally more integrated business model.

To be an EM leader, a conglomerate would need to combine operational efficiency with knowledge of other territories by building effective collaboration and partnership management capabilities. Larsen & Toubro created a systematic approach to managing partnership performance, assessing partners on the technical abilities needed for critical deliverables, and testing risk/return scenarios for projects. A potential partner’s past performance is crucial for the company; lessons from previous projects are incorporated into any agreement, and clauses on liability are drafted after legal due diligence.

A global specialist needs to leverage its worldwide brand image along with a strong focus on research and development and on building deep insight into one industry. Alfa Group operates in several industries in Mexico and is particularly strong in consumer-driven innovation and in capturing market trends. It leverages its state-of-the-art research and development center to build industry-leading food processing technologies and then commercializes them into consumer products relevant for global markets.

A tech platform conglomerate needs a strong platform and talent base to address consumer needs through fast-paced innovation. Reliance Industries has set up an incubation center called GenNextHub to catalyze a startup ecosystem that will develop fintech, Internet of Things, and other capabilities.

Finally, an investment group would have to hone its investment discipline to outperform market cycles and achieve superior shareholder returns. Votorantim, one of the largest industrial conglomerates in Latin America, has been improving its governance model, which favors greater autonomy of subsidiary companies to allow for more agility in responding to changing market dynamics.

Although the conglomerate model has come under increasing scrutiny in some quarters, it still has plenty of life in emerging markets, particularly if the right choices are made by conglomerates aligning themselves with one of the five archetypes. For those embracing each archetype, developing the capabilities needed to follow that path in a coherent way will be critical to improving performance. This will lay the foundation for a successful next wave of expansion and an exciting future for emerging market conglomerates.

Author profiles:

- Shashank Tripathi is a partner with PwC India, based in Mumbai. He specializes in growth strategies in the industrial products and aerospace and defense industries, and in creating government platforms for large-scale strategic transformation.

- Eduardo Fusaro is an advisor to executives with Strategy&, PwC's strategy consulting business, and has worked with industrial and conglomerate clients in Brazil for more than 16 years. He is a partner with PwC Canada, based in Toronto.

- Anurag Garg is a director with PwC India. Based in Delhi, he works with the aerospace and defense industry, advising Indian and international companies on capabilities-driven growth strategies, digital transformation, due diligence, and strategy execution.