What the West Can Learn from Jugaad

The structured approach to innovation favored by mature companies can’t deliver the agility and differentiation they need today.

For three generations, Gustavo Grobocopatel’s family had pursued a small-scale, subsistence model of farming in Argentina. Grobocopatel dreamed of growing his farm into a larger, more sustainable enterprise, but his vision was hindered by scarcity. For one thing, he had difficulty accessing large tracts of land. Although Argentina is a vast country, farmland is hard to come by. Only 10 percent of the land is arable, and much of that is controlled by a few owners who are reluctant to part with it. Grobocopatel also faced a shortage of the skilled labor needed to scale up his business—people who could fertilize, sow, tend, and harvest crops. In Argentina, such labor is in limited supply, is not formally organized, is spread out across the country, and can be costly to hire, especially during peak harvest seasons. Finally, he didn’t have the capital to buy the farm equipment he needed. Funding opportunities for bootstrapping new businesses are very limited for entrepreneurs in Argentina.

Instead of giving in to these challenges, Grobocopatel developed an ingenious business model. He overcame the scarcity of land by leasing rather than acquiring it. He dealt with the scarcity of labor by subcontracting every aspect of farmwork to a network of specialized service providers, giving him access to “freelance” laborers whom he could hire as needed. And he overcame the cost of owning equipment and the lack of access to capital by renting the equipment needed from networks of small local companies. By cleverly leveraging a grassroots network of 3,800 small and midsized agricultural suppliers, Grobocopatel’s company, Los Grobo, which the entrepreneur founded in 1984, has evolved rapidly from a vertically integrated family business to an asset-light company. In 2010, it became the second-largest grain producer in Latin America, farming more than 300,000 hectares, trading 3 million tons of grain per year, and generating US$750 million in revenue—all without owning land or a single tractor or harvester. Having succeeded in Argentina, Grobocopatel is now exporting his “frugal farming” model to Brazil, Uruguay, and Paraguay.

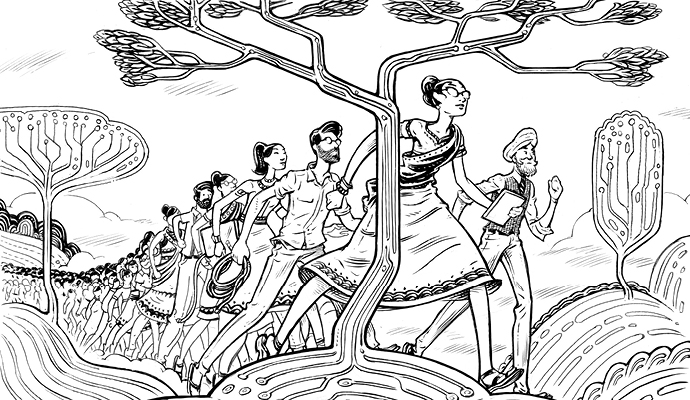

Los Grobo’s innovative business model was born out of adverse circumstances. It shows how a resilient mind-set can transform scarcity into opportunity by combining limited resources with inventiveness and a never-say-die attitude. This approach—whether it is aimed at creating a product, service, or business model—is what we call jugaad innovation. Jugaad is a colloquial Hindi word that roughly translates as “an innovative fix for your business; an improvised solution born from ingenuity and cleverness.” It is based on six operating principles: seek opportunity in adversity, do more with less, think and act flexibly, keep everything about the business simple, tap the margins of society for employees and customers, and follow your heart.

The extreme conditions that make jugaad innovation worthwhile have typically been more prevalent in emerging markets such as India, China, and Brazil than in the United States or Europe. But in recent years, developed economies have begun to exhibit many of the same aspects of scarcity, diversity, unpredictability, and interconnectivity, making these principles relevant to companies around the world.

Jugaad Lost

The jugaad spirit, also known as the “pioneer spirit,” was once common in North America and Europe as well—at least until their economies matured. During the 20th century, Western companies built up dedicated research and development departments aimed at institutionalizing and managing their innovation capabilities. This industrialization of the creative process led to a structured approach to innovation that spawned big budgets, standardized business processes, and controlled access to knowledge.

Most Western firms have assimilated the idea that an innovation system—like any other industrial system—will generate more output (inventions) if fed more input (resources). As a result, the structured innovation engine in most companies is capital intensive, requiring an abundant supply of financial and natural resources at a time when both are scarce. The 1,000 companies in the world that invest the most in innovation spent a whopping $603 billion on R&D in 2011. But what did they get in return? As the Booz & Company Global Innovation 1000 study has repeatedly shown since 2005, pumping more money into R&D doesn’t necessarily buy more innovation (see “The Global Innovation 1000: Making Ideas Work,” by Barry Jaruzelski, John Loehr, and Richard Holman, s+b, Winter 2012).

The size of their R&D investments caused many Western firms to become risk averse, and led them to implement standardized business processes such as Six Sigma and stage-gate analysis to manage their innovation projects. These structured processes were expected to drastically reduce uncertainty and the risk of failure. And they do have several well-documented benefits, including delivering volume-oriented economies of scale for standardized products and services, providing for the capital-intense needs of “big risk, big reward’’ R&D projects, and enabling more effective and efficient execution of innovation projects in stable environments. Yet structured processes can’t deliver the agility and differentiation that enterprises need in a fast-paced and volatile world. Six Sigma, for example, works marvelously when you are seeking to institutionalize “sameness.” But it can also be like a straitjacket: Once you get in, you are stuck, and when things start to change, you can’t move. Worse, the orthodox Six Sigma culture weeds out positive deviance—the unconventional and counterintuitive strategies used by pioneering employees to solve vexing business problems that can’t be addressed with traditional approaches.

The top-down R&D systems common in the West are also often unable to open up and integrate bottom-up input from employees and customers. But in today’s interconnected world, finding, sharing, and integrating knowledge from across the spectrum is essential. It’s clear that companies competing in this business environment need a new approach to innovation and growth —one that, like jugaad, is frugal, flexible, and participative.

Jugaad Regained

Instead of always using a hammer to deal with their problems, companies might find it helpful to use a screwdriver from time to time. In other words, we are not proposing that companies abandon their traditional structures and processes for innovation. Rather, they should expand their innovation tool kit.

Jugaad can bring value to conventional companies in a number of ways. They deliver economies of scope when companies need to tailor solutions to the specific needs of multiple customer segments in heterogeneous markets. They provide “soft” capital by unleashing the passion of employees, business partners, and existing and potential customers. And they enhance flexibility to better manage unexpected challenges and harsh constraints through the improvisational use of limited resources. For companies attempting to combine a jugaad-like approach with their existing R&D systems, we offer two suggestions.

1. Prioritize the principles. At the corporate level, let industry dynamics and your company’s strategic requirements determine which jugaad principles are most critical for your business success. For instance, if you are a premium retailer that sells luxury items, “do more with less” and “tap the margins of society” may not be of critical relevance; however, “keep it simple” may be crucial to streamlining the service experience for high-end customers. If you are a consumer products manufacturer like Procter & Gamble or Whirlpool, you may choose to “do more with less” by creating new frugal products for buyers whose purchasing power is waning. Similarly, Western companies in industries undergoing major turmoil, such as pharmaceuticals and automotive, would be wise to “seek opportunity in adversity” and “think and act flexibly.”

2. Aim for the low-hanging fruit. Once you have decided which principles are of strategic importance to you, adopt them in small, manageable stages. If “keep it simple” has appeal, begin by simplifying the design of your products and making them easier to use and maintain. Likewise, if you are attempting to “do more with less,” you can demonstrate frugality by first reusing components across existing product lines. Later, you can develop your frugal mind-set by designing entirely new, very affordable, high-quality products. Finally, if you are an enlightened bank that wants to “tap the margins of society”—that is, the 60 million Americans who are “unbanked” or “under-banked”—you can first partner with an organization like the Center for Financial Services Innovation and pilot financial inclusion solutions in a few U.S. cities before scaling them up nationally. (But you’d better hurry, because nimble startups and established companies like Walmart are already offering basic banking services to underserved communities.)

To simultaneously deal with low-volatility, resource-rich settings and high-volatility, resource-constrained settings, companies need two sets of innovation capabilities: the structured capability, with its volume-oriented economies of scale, hard capital, and efficiency, and the jugaad capability, with its value-oriented economies of scope, soft capital, and flexibility. Mature companies that strike this innovation balance will be better positioned for success in today’s complex, turbulent markets. ![]()

Reprint No. 00143

Author profiles:

- Navi Radjou is a Silicon Valley–based strategy consultant, a World Economic Forum faculty member, and a fellow at the University of Cambridge’s Judge Business School.

- Jaideep Prabhu is the Jawaharlal Nehru Professor of Indian Business and Enterprise and director of the Centre for India & Global Business at the University of Cambridge’s Judge Business School.

- Simone Ahuja is the founder of Blood Orange, a marketing and strategy consultancy with content production capabilities headquartered in Minneapolis and Mumbai.

- This article is adapted from the authors’ book, Jugaad Innovation: Think Frugal, Be Flexible, Generate Breakthrough Growth (Jossey-Bass, 2012).