The Paradox of Charles Handy

Vicar and visionary, modern management’s most eminent philosopher says it takes a village to build a company.

(originally published by Booz & Company)Past the village, down a country road, off a gravel path sits a 17th-century farm laborer’s cottage: an unlikely set of directions to one of the world’s most admired management thinkers. Yet it is here, in this home nestled among the wheat fields of England’s East Anglia, that Charles B. Handy has written some of the most influential, and prophetic, works of business literature.

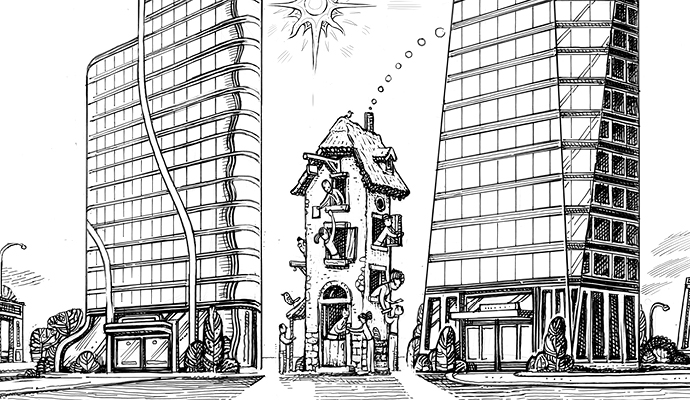

But the choice of such a tranquil setting to unravel vexing and stressful questions about the present and future of corporations is far less incongruous than it appears. Indeed, Mr. Handy finds in the village a metaphor and a model for human organization that is all the more striking for its simplicity and cohesiveness. He suggests that the current form of shareholder-dominated corporate capitalism, with all its complexity and conflict, is not sustainable, and will give way — must give way — to a simpler and more flexible form of private enterprise. This new form would promote greater collaboration and understanding among multiple constituents who share in the benefits and challenges of being part of one company, but who have distinct roles and different stakes and expectations, and are rewarded differently, depending on their purposes and contributions.

“A company ought to be a community, a community that you belong to, like a village,” Mr. Handy says. “Nobody owns a village. You are a member and you have rights. Shareholders will become financiers, and they will get rewarded according to the risk they assume, but they’re not to be called owners. And workers won’t be workers, they’ll be citizens, and they will have rights. And those rights will include a share in the profits that they have created.”

In The Age of Unreason, Mr. Handy describes a community-oriented, front-line-led “federal organization,” in which power and responsibility devolve from a small corporate center to business units and, ultimately, to those closest to the action. In federal organizations, he writes, “the initiative, the drive, and the energy come mostly from the parts, with the center an influencing force, relatively low in profile.” Still, the center “holds some decisions very tight to itself — usually and crucially, the choice of how to spend new money and where and when to place people.”

Furthermore, people have lived and worked in villages since the dawn of civilization. The corporation, notes Mr. Handy, is a young concept, little more than a century old. One could argue, too, that the notion of a lively village — with its unabashed humanity — is a more appropriate way to look at what the corporation should be in the 21st century than the constrained and impersonal entity it has been. As the author wrote in Gods of Management: The Changing Work of Organizations: “Villages are small and personal, and their inhabitants have names, characters, and personalities. What more appropriate concept on which to base our institutions of the future than the ancient organic social unit whose flexibility and strength sustained human society through millennia?”

If this vision of the future organization sounds far-fetched (and even some of Mr. Handy’s most ardent admirers believe it does), consider that he has made similarly provocative predictions for the past 25 years, and more often than not, time has proved him right. The rise of nontraditional work practices such as outsourcing, telecommuting, and “portfolio careers” (a term he coined in the 1980s to describe people who work for themselves and serve a portfolio of individuals and entities) seemed just as remote when Mr. Handy first began writing about them.

Mr. Handy is also widely recognized and revered for his contributions to furthering our understanding of business in the context of personal and ethical questions. “If Peter Drucker is responsible for legitimizing the field of management and Tom Peters for popularizing it, then Charles Handy should be known as the person who gave it a philosophical elegance and eloquence that was missing from the field,” says Warren Bennis, himself one of the most prominent scholars and writers in the discipline of leadership and management and a close friend of Charles Handy and his wife, Elizabeth.

Professor Bennis met Mr. Handy at the Sloan School of Management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1966, when the former was a professor and the latter a student in MIT’s executive program. But Professor Bennis has considered the extended Handy family his closest friends since he suffered a massive heart attack while on a visit to London, and spent three months convalescing in their tiny apartment. “That did solidify our friendship, which is deep and old and goes way beyond collegiality,” Professor Bennis says.

As I strolled with Mr. Handy, 72, and Mrs. Handy, 61, on a crisp morning this past spring, he commented that nothing has changed and everything has changed in his village in the last 100 years. The farmer down the lane plants wheat, just as his father and grandfather did, but today he harvests it himself with modern machinery. The sturdy earthen-walled cottages surrounding the farm no longer house workers, but are instead homes for London commuters and “fleas.” Fleas is Mr. Handy’s word for independent professionals who work for a portfolio of clients rather than building a career with one corporate “elephant.” One neighbor is a cabinetmaker; another is a globe-trotting international attorney.

“We’ve got a lot of public footpaths around this village, connecting little farmhouses with churches and shops and so on, because people walked,” Mr. Handy observes. “Way back 150 years ago, that was how people related. You married someone within walking distance. And there was so little to do in the village that everyone did go to church. You knew what you had to do, you knew who you were meant to be,” he says. “Today we have the same population, but totally different kinds of people, living and working quite differently.”

A Different Path

Mr. Handy might easily have lived a traditional village life. He grew up in St. Michael’s Vicarage, in Ireland’s County Kildare, where his father was the rector of two small parishes in the country west of Dublin. His great-grandfather was archdeacon of Dublin at the end of the 19th century. His brother is a country vicar in Ireland today.

But Mr. Handy sought a different path. He left Ireland for Oxford University, where he graduated in 1956 with first-class honors in “Greats,” the study of classics, history, and philosophy. After graduation, he joined Shell International, the giant Dutch oil and gas company, which has long been an incubator for management visionaries. He spent 10 years with Shell as a marketing director, economist, and management educator, in London and Southeast Asia. While working in Kuala Lumpur, he met his future wife, Elizabeth, who at the time was a teacher. There, for the first of several times, she changed the course of his life.

“I’d given my life to Shell, and I really was very pleased about it,” Mr. Handy says. “[I changed] only after marrying Elizabeth, who said to me, ‘You must be out of your mind, handing your life over to these people. They own you.’ ‘Oh,’ I said, and I was a bit taken aback, but I began to realize that she was right. They sent us to places we didn’t want to go, and to do jobs I didn’t particularly want to do. They were saying it’s all part of long-term development and getting your hands wet.”

When Shell asked Mr. Handy to go to Liberia, he decided the time had come to take back control of his life, and he left the company in 1965 to attend the Sloan executive program at MIT. He returned to England in 1967 to create the first, and only, Sloan program outside the U.S., at the London Business School (LBS), Britain’s first graduate business school. Mr. Handy was the first dean of the Sloan program at LBS, a one-year course of study designed for experienced executives, typically in their mid- to late 30s. He became a full professor at LBS, specializing in managerial psychology, in 1972.

The program was an unusual one, and LBS was an unusual school at that time. Universities in the United Kingdom and, indeed, Europe had not previously offered graduate studies in business, which was not considered a scholarly pursuit. Nor had anyone offered a midcareer program of management study for experienced executives. There were few guidelines for how to proceed, aside from the experience of the MIT program. And by all accounts, Mr. Handy was an unusual business professor, packing his executive students off to the theater in their first week of class, and as likely to assign Dostoevsky as Drucker. But colleagues say he left a mark on LBS that remains.

“He gave it a very particular imprimatur,” says Michael Hay, deputy dean of the London Business School. “Sloan participants are very diverse — we now take 64, drawn from 50 countries — and they’re all in some sort of transition. It’s a wonderful opportunity for them to take a step back and take stock of what they’ve done and what they want to accomplish in the future.”

The Gods of Management

While he was at LBS, Mr. Handy wrote his first book, Understanding Organizations (1976). Although in many ways it is a traditional textbook, the heavily footnoted survey of management literature also provided the first glimpse of Mr. Handy’s overarching thesis: Organizations are not inanimate objects but vibrant microcosms of human societies, and those who seek to manage them and work within them must better understand the needs and motivations of the individual people who make up the organization and comprehend how their collective behavior determines organizational behavior. Translated into five languages, Understanding Organizations has sold more than 600,000 copies in four editions and has been required reading for a generation of business-school students.

Mr. Handy truly found his voice, and perhaps his vocation, however, in his second book, Gods of Management (1978). At first glance, the book seems to be a clever application of the metaphor of the Greek gods to personality types and corporate cultures. But on deeper reading, it is revealed as a provocative, almost polemic, call for change. Mr. Handy categorized corporate cultures by four personality types, each represented by an appropriate Greek god — Zeus, Apollo, Athena, and Dionysus.

Cultures typified by the charismatic founder/leader Zeus, he says, are managed by sheer force of will, respect for the leader’s outsized talent, and the pleasure of belonging to an inner circle. This culture works best in small startup organizations. The Apollo culture, which has dominated large corporate organizations for the past two decades or more, is one with clearly delineated rules, roles, and procedures, and management by hierarchy. This culture works best in stable, predictable markets and industries. The Athena culture is collaborative and task-based, drawing upon flexible teams of professionals who solve particular problems, and then move on to the next ones. Historically, the Athena culture has worked best in consulting firms, advertising agencies, and other fields where ideas are the product and where expertise can be applied in very specific ways. Finally, the culture of Dionysus, god of wine and song, is existential, typified by independent specialists who enter the organization only to achieve their own purposes. It works best where individual talent is at a premium and people are encouraged to work independently.

Conflicts inevitably arise when the cultures are mixed in inappropriate ways. Scrappy startups become more Apollonian as they grow, pitting Zeus and the founders’ club against a middle management dedicated to preserving order. Athenian organizations also become more rules-based as they grow, alienating partners who would rather be judged by outcomes on specific projects than evaluated by formal appraisal procedures. Dionysians are often unmanageable by conventional means, such as perks, promotions, or the threat of dismissal; they also prefer to sell their services to a succession of highest bidders rather than accept the apparent security of a stable wage.

The problem for society, as Mr. Handy wrote in Gods of Management and has elaborated on ever since, is that changes in education, the economy, and the values of people have not been mirrored by a corresponding change in corporate cultures. An emphasis on individual learning, growing affluence, and a market that prizes ideas and intellectual property above all else have prompted the population of Athenians and Dionysians to grow. These highly qualified individuals will not work for Apollo, or will do so only grudgingly, which undermines the goals of the traditional organization and limits workers’ own opportunities. The resistance to Apollo and “bureaucratic corporatism” will only grow, Mr. Handy says.

So what can be done? The answer, he posits, can be found in the triumph of Athens. By this he means the formation of the kind of adaptable, centerless organization that he has variously described as a shamrock, with the three leaves representing different groups of people with different goals, tasks, and rewards; as the aforementioned federation, with business units as semiautonomous states; and ultimately as the village, the most flexible, organic, and time-tested organizational form of all. The most talented people and the highest-value work will flow to and from villages of like-minded individuals, bound by a common purpose and managed by reciprocal trust. Villages will shrink and grow as market needs dictate, and no single village is likely to support a lifelong career based on a single pursuit. Outsourcing and subcontracting will abound.

A Practical Philosopher

Mr. Handy’s scenario is not calculated to make him popular. “At conferences people come up to me and say, ‘I really disagree with you. It’s a horrible world you’re describing.’ And I say, ‘I agree it’s a horrible world; what are you disagreeing about? Do you think it’s not going to happen?’ And they say, ‘Yes, I can see it’s going to happen, but I don’t agree with you that it’s a good thing.’ And I say, ‘I’m not saying it’s a good thing. I’m just saying it’s going to happen,’” Mr. Handy says. “They hate what I’m saying. The managers hate it because they can see the difficulty of managing these new organizations. The economists and the stockholders hate it because they can see their power diminishing, and the individuals hate it because it’s dangerous.”

This interchange is typical Handy. He never prescribes, he describes. He doesn’t provide answers, he asks questions. One does not read Mr. Handy for pat solutions to today’s problems, but for insights into how and why they have developed. He doesn’t tell the reader how to reorganize a company, but rather offers a more coherent way to look at organizations.

This strikes a chord with leaders who find his honesty refreshing and his insights into human dynamics in organizations extremely valuable. “Charles really is about the practical way that organizations work, and for me, that is the reason I like him more than anyone else I’ve read,” says Marjorie Scardino, president and chief executive of Pearson Publishing Group, the British publishing giant. “He recognized that the corporation was a social organization and that the only way it was going to work was to treat it as a social organization with a purpose,” she says. “Every time I talk to him I feel I learn something brilliant. I feel more lucid.”

Ms. Scardino concedes that a broad implementation of Mr. Handy’s concepts is difficult to achieve, particularly in a publicly held company, but that has not stopped her from trying. “I have said at various times and places that I view profit as a by-product of the company doing well, and that is fundamentally what Charles’s message is too,” she says. “Right now it’s hard to convince shareholders that [over the] long term, the culture of the corporation, the ways it nourishes people, matters to the bottom line. But Charles’s influence is visible in the changes you see in the human resources approaches of companies, the fact that everyone now says we are dependent on our people, that we look seriously at lifestyle issues, that we realize people have lives outside of work.”

Mr. Handy himself downplays his impact on management practices, although he believes he exerts a sort of “indirect influence” through his books and speaking engagements. A self-described “Dionysian with streaks of Athena,” Mr. Handy enjoyed his time in academia, but says he soon grew disillusioned.

“I really thought that I would put a new breed of managers into British industry, who would be more civilized and make it more effective and really change the bumbling, cruel place,” Mr. Handy says. “But all these guys just became consultants. I mean, literally. Or bankers. Liz said to me, ‘What the hell are you doing? Making rich kids richer.’ They were nice kids, but I thought, hey, what am I doing? Is this a finishing school for rich kids?

“And also, I realized, of course, that the reason they were going to be consultants and bankers was because that was what we taught them. We taught them analytical skills. We didn’t teach them to manage,” he says. “You can’t teach management in a classroom.”

Although prodded to change again by Mrs. Handy, Mr. Handy says it was actually the death of his father, and a subsequent bit of soul-searching, that prompted him to leave LBS in 1977. He says that, though proud of his father, he had always felt disappointed in him, for the limitations of his seemingly simple life. But at his father’s funeral he was struck by the mourners’ tears, by the number of lives his father had touched. He began to think deeply about the purpose of his own life; though he had never considered himself a religious person, he seriously considered joining the clergy, in the Church of England.

“I actually talked to a couple of bishops about getting ordained,” Mr. Handy says. “And they were really quite rude. They said, ‘Charles, you could be a great bishop, but I don’t think you’d ever make it as a curate.’ But, they said, there is this job, a funny job at Windsor Castle, where they’ve tried to draw together the leaders of society and the churches to talk about the issues in society and to trade ideas. They’re looking for a person to run that. Would you like to apply?’”

Windsor Castle, an official residence of the queen and the largest occupied castle in the world, had long hosted various educational programs. But this was to be something different, a blend of spiritualism, sociology, and management thinking that seemed tailor-made for Mr. Handy’s mix of interests and skills. For the next four years, he was warden of St. George’s House at Windsor Castle, managing a program created by Prince Philip and the then dean of Windsor, Robin Woods. He ran workshops on such topics as justice; the future of work; power and responsibility in society; and other Handyesque themes. Captains of industry, trade union leaders, civil servants, teachers, and politicians mingled with bishops and chaplains.

This was also a time when Mr. Handy began to address spirituality and his own spiritual roots more directly, and he began attending services regularly, something he had not done before and has not done since.

Mr. Handy says that he is not “conventionally religious,” but that through his upbringing, and the time he spent at Windsor, the relevant lessons of the great religions have crept into his DNA and his work. “When you grow up steeped in this stuff, your earliest inclination is to rebel against it all, and then you discover that it’s actually part of you,” he says. “I don’t believe the dogma of any religion. But I do feel that we hanker after a deeper meaning in life than just surviving.”

Mr. Handy’s apparent faith has prompted occasional requests for him to preach, which he politely declines. Nonetheless, he was for 10 years the lone layperson among a rotating cast of bishops, priests, and rabbis on BBC Radio’s 7:00 a.m. broadcast, Thought for the Day. The best of his two-minute, 45-second reflections on life and work were later published as Waiting for the Mountain to Move and Other Reflections on Life. Heard by millions of Britons every morning, Thought for the Day turned Mr. Handy into a public personality in the U.K., where it is still common for bookstores to devote entire shelves to his works. It was as if the Today show had granted Peter Drucker a regular slot. Mr. Handy left the show because he felt he was not religious enough for it. But for many of his followers, his openness about spirituality is part of the strength of his message.

“There is always a moral and ethical component to whatever issues he is raising, whether how to be a more effective leader or practical managerial questions,” says James O’Toole, a research professor in the Center for Effective Organizations at the University of Southern California. “He never takes those higher values off the table. I always keep thinking when he starts off that ultimately we’re going to get a Christian message, but he never goes there. He shows you that issues of morality and ethics are present whether you’re a believer or an unbeliever. It’s a very transcendent moral view.”

Of his time at Windsor, Mr. Handy says, “It was an interesting experience; it got me out of the business-school world, but after four years, I was ready to move on.” Once again, it was Mrs. Handy who said, “You’ve got to get out of organizations, you’ve got to be a writer.” He says, “By then I had written one book and thought perhaps I could write another. That was scary, actually. That was very scary.”

It was 1981 and Mr. Handy was 49, with two school-age children. He did a bit of consulting, a bit of executive training, a bit of lecturing, none of which paid very much. But he also began to write full time, and the books began to flow. Building on the themes he first explored in Gods of Management, he produced The Age of Unreason, his first book to be published in the United States, and the work that positioned him firmly among the world’s management gurus, a term he disdains. “To call Charles a guru would probably send a frisson down his spine,” Professor Bennis says. (Some say The Economist first coined the phrase “management guru” to describe Mr. Handy himself.)

Optimistic and Unreasonable

The Age of Unreason was an immediate success, and was named by both Business Week and Fortune as one of the 10 best business books of the year for 1990. Where Gods had described four common corporate cultures and suggested that changes in society argued for similar changes in organizations, The Age of Unreason — its title taken from a George Bernard Shaw observation that all progress depends on unreasonable people, for they are the ones who try to change the world, while reasonable people simply adapt to it — stated that technology had launched an era of wrenching discontinuous change that would transform every aspect of work and society.

“That book, Age of Unreason, did it for me,” says Tom Peters, whose first book, In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America’s Best-Run Companies (Harper & Row, 1982), written with Robert Waterman, created the popular management book genre. “The fundamental model of what an organization was going to become, what a career would be; he made a single statement in a single place with a book that was small enough to hold in your hand. I thought it was a real landmark. It sure as hell jolted me,” Mr. Peters says.

In an era when changes in business and society will be “discontinuous,” or patternless, The Age of Unreason suggests that our thinking must become just as uninhibited and “unreasonable” in order to seize the opportunities such variability presents. The book does not predict the future. Indeed, it asserts the future is and will remain unpredictable. In a series of self-examination exercises, Mr. Handy shows how individuals can reassess their lives and work and the organizations within which they operate.

The Age of Unreason was not only Mr. Handy’s first book to be published in the United States; it was also the first of its kind for its U.S. publisher. “We really hadn’t published anything like this book, which was so broad reaching and personal,” says Carol Franco, director of the Harvard Business School Press. “We thought the book was so prescient. He identified trends that we were just beginning to get a sense about. What he brought to the book, and what he brings in his personal approach, is a sense that business is community with purpose,” she says. “The book saw discontinuous trends that gave people a huge opportunity to live a full life, and gave shape to a different kind of organization.”

The book resonated with the times, particularly in the United States, where the “greed is good” era of the 1980s had given way to a deep recession and pervasive self-doubt. Business leaders and employees alike were becoming more concerned about social responsibility, motivation, and work/life balance. The Age of Unreason bridged the concepts of business success and personal fulfillment, articulating thoughts that had been present through the 1980s and would resonate even during the dot-com boom of the 1990s.

Despite its ominous-sounding title, The Age of Unreason was a fundamentally optimistic book, which suggested that even unexpected, radical change could be embraced as an opportunity. The optimism partly reflected Mr. Handy’s upbeat nature and personal philosophy: To live without hope is dismal, as he puts it. But in the years that followed the book’s publication, and even as some of its predictions came true, he came to feel he had been naive about some of the ramifications.

The sequel, The Age of Paradox, has a more wary tone. Chapter one is titled “We Are Not Where We Hoped to Be,” and subtitled “It Doesn’t Make Sense.” In essence, this book concedes that socioeconomic change has proceeded at an even faster and more deranging pace than the author had anticipated, creating a world full of paradox. Technology has increased wealth and consumption among a few while reducing employment and incomes for many. Opportunities for personal fulfillment are complicated by demands for ever-greater efficiency, and the new freedom to pursue more flexible lifestyles that account for our personal and professional lives only increases the inequities between the skilled or talented haves and the less fortunate have-nots. Mr. Handy returns in The Age of Paradox to the notion of the village, here called the existential enterprise, which he suggests should better serve a host of constituencies — employees, neighbors, customers — as well as shareholders. He remains hopeful about the opportunities to come, but worried about the unintended human costs of his vision of a new capitalism.

Warren Bennis says that Mr. Handy’s work brought a new depth to business literature. And Jim Collins, author of Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap ... and Others Don’t (HarperBusiness, 2001), says, “He has always carried himself with such grace, a true statesman of the field. He’s like a friendly, wizened dean of faculty for the world of independent thinkers.”

Although Mr. Handy’s days as a Shell executive are now distant, they still stand him in good stead with corporate audiences. “He has enough work experience to be credible in his anecdotes,” says Brook Manville, chief learning officer of Saba Software Inc., and author, with Princeton University professor Josiah Ober, of A Company of Citizens: What the World’s First Democracy Teaches Leaders about Creating Great Organizations (Harvard Business School Press, 2003). “Handy has taken what is a relatively dry domain — organizational design — and through his artful use of metaphor made it much more accessible and meaningful.”

A Persuasive Presenter

Mr. Handy is as clever a speaker as he is a writer. Harvard Business School Press put him on the road to promote his books — something he had never really done before — and he discovered a talent for public presentations. He became a fixture on the international lecture circuit, which proved to be a lucrative addition to his writing. “Charles’s persona is that he thinks primarily of himself as a writer, but he is also a magnificent presenter, and he has done very well at that pursuit,” says Professor Bennis.

Though hardly a showman in the style of Mr. Peters, Mr. Handy is not above a bit of drama himself. He never uses PowerPoint slides, preferring to lecture with a Visualizer, a sort of high-tech overhead projector that allows him to add text and scribble in the margins as he speaks. He almost always draws a pair of overlapping sigmoid curves that he says illustrate a central paradox: Organizations or individuals must begin a second growth trajectory just when their first is peaking, because if they wait until it is in decline they will be too late. Once, when deprived of his Visualizer, he donned a white lab coat and spray-painted the two curves on a plastic wall.

But what really makes his presentations stand out is the quality of Mr. Handy’s speech, which, like his writing, is thoughtful, measured, and full of rich metaphors and amusing anecdotes. “On at least three or four occasions, I have heard Charles speak to American executives, and I’ve never heard any business speaker capture them the way he does,” says USC’s Professor O’Toole. “He talks books. It comes across so eloquently that it’s very enticing. The force of his personality gives his work real moral authority. You listen, you respect, and you trust him.”

Michael Bell, an analyst with Gartner Inc., recalls bringing Mr. Handy to speak to an organization of commercial real estate specialists when Mr. Bell was an executive at Dun and Bradstreet. “His pitch was, ‘This reminds me of when I stood in front of a bunch of librarians and suggested to them the notion that the library may go away. I have a similar message for you guys,’” says Mr. Bell. “‘The office as we know it may be a thing of the past. The office is really a social place, a place to meet and greet.’ It was striking. He was really one of the early provocative thinkers about the virtual workplace.”

Mr. Handy’s status among the world’s management thinkers grew as he published more books: Understanding Schools as Organizations; Understanding Voluntary Organizations: How to Make Them Function Effectively; Beyond Certainty: The Changing Worlds of Organizations; Inside Organizations: 21 Ideas for Managers. His audience grew, and his lecture fees increased, paying for elegant additions to the once-humble cottage. There is now a high-beamed, barn-shaped writing room with a glass wall looking south across the waves of wheat for Charles, and a professional-grade darkroom and studio for Elizabeth, who has built a career as a portrait photographer. The Handys also have a stately town house in London, filled with Elizabeth’s photography, and a vacation villa in Tuscany. They live well, though not lavishly.

What Life Is For

Sometime in the last 10 years, however, Mr. Handy says, he again began to feel restless. He was tired of flying around the world giving lectures, and the role of organizational voyeur interested him less. At the same time, Mrs. Handy, who had long played the role of his business manager — rebuffing requests from unsuitable would-be clients, making sure fees were paid — wanted to devote more time to her photography. With the children grown and established in their own careers (Kate, 36, lives in New Zealand, where she is an osteopath, and Scott, 34, is an actor based in London), it was time for another change.

The solution they arrived at is unusual, but thoroughly in keeping with Mr. Handy’s concepts. They now split the year, spending six months at a time on his work and six months on hers. Mr. Handy says the arrangement works because they still enjoy each other’s company, and he believes it may have saved the relationship. He likes to joke that, like many men his age, he is on his second marriage, but in his case to the same woman.

Another reason the split-season career works for the Handys is that they found they enjoyed collaborating on books and other projects. The first fruit of this process was The New Alchemists, which matched Charles’s profiles of London entrepreneurs with Elizabeth’s unusual composite portraits. More recently, they have produced Reinvented Lives: Women at Sixty: A Celebration, coupling Elizabeth’s photographs with 28 women’s stories in their own words, and an opening essay by Charles. They are currently plotting a book on couples around the world who, like themselves, share a career.

Mr. Handy’s own books have turned away from the subject of organizational behavior, examining deeper but perhaps less clearly defined territory, like what a life is for. The first of these was The Hungry Spirit, subtitled Beyond Capitalism: A Quest for Purpose in the Modern World. Critics were not kind to the book, with some suggesting that it was disingenuous for a person of Mr. Handy’s affluence to say that money is a means, not an end, and others accusing him of being anticapitalist. Mr. Handy says he felt stung and misunderstood.

“They said that this man seems not to believe in the stock market, and no, I didn’t believe in the stock market,” Mr. Handy says. “But in 1997 that was a very strange thing to say.” He returned to some of the same themes, but with much more critical acceptance, in The Elephant and the Flea: Looking Backwards to the Future. Written in the form of an autobiography, the book is deeply reflective about his own life and explores the shift from traditional long-term careers in major corporations (the elephants) to the life of a free-floating freelancer (a flea), exemplified of course by Mr. Handy’s own life story. Organizations are changing and will continue to change, but not nearly rapidly enough to suit Mr. Handy and other Dionysians like him. The solution? Figure out what you like to do and who will pay for it, and be a vendor to the elephants, rather than their employee.

“It is a much more satisfying, adult-to-adult, relationship,’’ says Mr. Handy. “Versus being an employee, which is always child-to-never-satisfied-parent.” To those who say he is unique, and that most people lack the talent or skills to strike out on their own, Mr. Handy says that they merely need to look more closely at their own abilities.

“This is the only good thing about working 10 years for Shell,” Mr. Handy says. “I can actually say to them, look, I was a Shell executive. I didn’t know I could write. I bet you have a talent. You may not know what it is, but I suspect your mother knows. Or your wife knows, or your husband knows, or your best friend knows. I bet you’ve got something. And the trick is to turn that into a commercial product. Something somebody else wants. It’s quite probable that your organization doesn’t know because otherwise they would be doing something with it.”

Of course, some people like to belong to and work for organizations. There is a pleasure to be had in contributing to a larger purpose, which Mr. Handy does not deny. He also worries that a nation of fleas would likely be a very selfish place, and not a place he would choose to live. So he is not about to give up on reshaping organizations.

And indeed, the growing adoption of corporate social responsibility programs and employee-empowerment programs suggests that organizations are at least beginning to think in Handyesque terms, if not adopting his recommendations wholesale. Society’s view of corporations is evolving, and people are beginning to demand that these organizations meet ethical as well as professional standards. Sustainable business practices are becoming a competitive advantage, as the best and brightest professionals want to work for, and customers prefer to buy from, companies that do more than make money, pay taxes, and obey the law.

Mr. Handy says the collapse of the 1990s market bubble, the Enron scandal, and other recent financial calamities only reinforce his long-standing message. The purpose of a business is not simply to make a profit. He cites David Packard, cofounder of Hewlett-Packard Company, whose edict was: A group of people get together and exist as an institution that we call a company, so they are able to accomplish collectively what they could not accomplish separately. They make a contribution to society.

As Pearson’s Ms. Scardino noted, this message often does not resonate with shareholders, who remain fixated on quarterly earnings growth. To that, Mr. Handy replies that the whole notion of shareholders as owners of the company is an outdated fiction. Most shareholders never put any money into the company, he notes; they simply trade shares with other traders. They deserve a return on investment, but not a say in how the company is managed or the power to sell it to would-be acquirers. That power should reside with the founders and the employees: the community.

Charles Handy says he knows this model may be a long time coming, but he says he is just as certain that the current model is no longer sustainable. “My solutions are far too radical for the short term,” he says. “The idea that the ownership models of companies have got to be abandoned in favor of community models sounds mad. But I sincerely believe that it will come to that within 20 years.” ![]()

Reprint No. 03309

Lawrence M. Fisher (lafish3@attbi.com), a contributing editor to strategy+business, has covered technology for the New York Times for more than 15 years, and has written for dozens of other business publications. Mr. Fisher is based in San Francisco.