An Interview with Charles Handy

(originally published by Booz & Company) Charles Handy is Europe's best known and most influential management thinker. In an interview with Joel Kurtzman, editor of Strategy & Business, Mr. Handy elaborates on his concept of 'membership community' for the corporate model of the future. 'Corporations are not things, they are the people who run them,' he says. 'In order to hold people inside the corporation, we can't really talk about them being employees anymore.'

Charles Handy is Europe's best known and most influential management thinker. In an interview with Joel Kurtzman, editor of Strategy & Business, Mr. Handy elaborates on his concept of 'membership community' for the corporate model of the future. 'Corporations are not things, they are the people who run them,' he says. 'In order to hold people inside the corporation, we can't really talk about them being employees anymore.'

Mr. Handy believes the Machine Age corporate model is disappearing quickly, as corporations open themselves up to strategic alliances, virtual business and other temptations of the Information Age. What will be missing, he says, is commitment. 'Unless we develop a more sophisticated model of the organization, the corporation will become just a box of contracts with no commitment on anyone's part at all. That would be a tragedy.'

Mr. Handy believes that membership corporations are the answer to this dilemma. 'To hold people to the corporation, there has to be some kind of continuity and some sense of belonging. We also have to talk about commitment, but we have to talk about it both ways - corporation to member, member to corporation.' His concept of membership includes not only employees but other people with a stake in the corporation, including financial contributors and major shareholders.

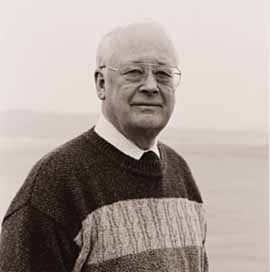

Mr. Handy, who was born in Ireland in 1932, has had a long and distinguished career in business and academia. He is a graduate of Oxford University, the Sloan School at M.I.T. and a founder of the London Business School. His most recent book was published as 'The Age of Paradox' (Harvard Business School Press) in the United States and as 'The Empty Raincoat' elsewhere.

Charles Handy is Europe's best known and most influential management thinker. Walk into any bookstore and you will probably see stacks of his latest work, "The Empty Raincoat" ("The Age Of Paradox," Harvard Business School Press, in the United States), in large displays with life-size portraits of the author. Switch on the BBC and you are likely to hear his voice.Mr. Handy, who was born in Kildare, Ireland, in 1932, has had a long and distinguished career in business and academia. He started out at Oriel College in Oxford and at Royal Dutch Shell in Asia, went on to the Sloan School at M.I.T., where he received his M.B.A., and was later a founder of the London Business School. His early books were about organizational dynamics and behavior. Mr. Handy does not see business as removed from society. He views it as an integral element in the life of humanity. As a consequence, he thinks of himself more as a social philosopher than as a management theorist. In his view, business is an important element within the overall social fabric of any nation. But business must change to keep pace with the new realities. It must change structurally, to be more competitive and to fit with the way society has changed, and it must change strategically. In Mr. Handy's view, businesses must no longer simply be places to work and to produce a profit for the shareholders; they must become "membership communities." What follows are excerpts from a conversation with Mr. Handy at his home outside London.

S&B: You have written that the corporation is in the midst of a profound and historic transformation. Other management thinkers have offered similar observations. But you also offer a new model. How would you describe that model?

Charles Handy: The old corporate models grew out of the Machine Age, and that age is passing rapidly. Recently, I was talking to some German executives in Frankfurt. They were engineers who had built their organization as engineers build organizations. Their company was a work of great precision, rather like an automobile engine. Its functions could all be accurately designed and accurately measured. This model had served them well. But they began wondering about their organization in the future. They began to wonder if the model would work when the commodity that was being passed around was information, not metal. "We understand what we have to do to our organization with our brains,'' they said, "but in our hearts we don't know how to design an organization that is not a machine."

S&B:What did you tell them?

Charles Handy: Well, I told them that not many people really do know how to design an organization that is not a machine. I also told them there are a few places to start. For example, we no longer need to have all the people in the same place at the same time to get work done. There is now the core-periphery model with people working in the core while others work outside of the core. There is also the Federal model, where power is distributed. But I also told them about what I have been trying to do most recently, that is, design the corporate model around the concept of what I call the membership community. I believe that corporations should be membership communities because I believe corporations are not things, they are the people who run them.

S&B:How is the membership community structured?

Charles Handy: It is something quite different from what we now have. Let me give you some background. The old model of the corporation was a piece of property, a piece of real estate. It was, quite simply, the property of its owners. The owners were in the first instance the people who created the corporation. Then, increasingly, the owners were the financiers. That's just rubbish now. It's rather like saying that the people who provide you with a mortgage actually own your house when in my view they only do as a matter of last resort. It is also like saying, as people used to do, I'm afraid, that a man owns his wife, which now sounds quite absurd. So the property model of the corporation is outdated. Why should financiers have such power and talk the language of ownership just because they provided the money? People don't own people and corporations are people. It's all part of the Machine Age model.

Charles Handy: It is something quite different from what we now have. Let me give you some background. The old model of the corporation was a piece of property, a piece of real estate. It was, quite simply, the property of its owners. The owners were in the first instance the people who created the corporation. Then, increasingly, the owners were the financiers. That's just rubbish now. It's rather like saying that the people who provide you with a mortgage actually own your house when in my view they only do as a matter of last resort. It is also like saying, as people used to do, I'm afraid, that a man owns his wife, which now sounds quite absurd. So the property model of the corporation is outdated. Why should financiers have such power and talk the language of ownership just because they provided the money? People don't own people and corporations are people. It's all part of the Machine Age model.

S&B:So tell me, what is a membership community?

Charles Handy: Here then is the premise. In order to hold people inside the corporation, we can't really talk about them being employees anymore. To hold people to the corporation, there has to be some kind of continuity and some sense of belonging. We also have to talk about commitment, but we have to talk about it both ways--corporation to member, member to corporation. With the way corporations are evolving--with all this virtual business and all these alliances--my worry is that unless we develop a more sophisticated model of the organization, the corporation will become just a box of contracts with no commitment on anyone's part at all. That would be a tragedy. If that were to happen, it would mean that people would be put together on project teams from all over with no real sense of responsibility. What I want companies to develop is a concept of membership, which says that people with a large stake in the organization--those who are the great contributors, and yes, they include the financial contributors sometimes, the major shareholders--should be given membership rights. At the moment, we're asking responsibilities from people and giving them very few rights.

S&B:What would these rights entail?

Charles Handy: The right to have a say in the strategy of the company. The right to have a veto on the sale of the company and even in the merger of a company. You would have mergers but they would be by the members' agreement. And, of course, the right to a share in the value-added of the company, which I would express not so much by stock options, which I think are a rather dubious invention, but by having a share of revenue.

S&B:Don't you think it would be more difficult to raise capital if investors had less of a say in how the company was managed?

Charles Handy: You know, when Fortune magazine reviewed my latest book, "The Age of Paradox," they wrote that "Handy's solution is to abolish the stock market." That is not my intention at all. My aim is to reduce the powers of the shareholders--yes. But I believe in a strong, vigorous market. I don't think shareholders should have the power to sell the company over the heads of its people. Nor do I believe that the shareholders have the right to sack the board. But I do believe that those members of the stock market who have a serious commitment to the company--i.e., a big stake in it, 1 percent or more--should have membership rights, i.e., voting rights. They should have rights as should the senior employees and perhaps even the junior employees through the form of a trust fund. These trusts would have some block votes. So at least in one sense, performance would continue to be measured by return on shares and the market would serve its function. The markets would also ensure transparency. These are not anti-market propositions.

S&B:Would everyone who works for a corporation, in your model, be a member with the same rights and responsibilities you describe?

Charles Handy: In a word, no. Not everyone in the core, for example, has to be a member. There can be some people with whom you enter into ordinary contractual relationships and who simply work there. But the people upon whom your long-term future depends must be members.

S&B:Are you proposing a two-tier system with the members employed for the long haul and with others working on an as-needed basis?

Charles Handy: My model is not quite so simple. The members are the people on whom the corporation is dependent for its long-term future. But as far as titles go, I prefer to use the word professional rather than member because the thing about professionals is that they are competent in their own right and acknowledged as such. They are not just tools of the organization. This goes back to my basic concept of subsidiarity, which says you must leave as much power as possible as low as possible in the organization because that's where the knowledge and experience are. Subsidiarity is also at the heart of Federalism.

Now it seems to me that the principle of subsidiarity is at the heart of professionalism. Think for a moment about the doctor in the emergency room of a hospital. The doctor is in charge even though she may be straight out of medical school and her specialty training. The doctor is in total charge in that place at that time because she has the knowledge and skill. As a consequence, all the decisions are hers to make because she is a professional and because you are dependent upon her knowledge. The same is true for the lawyer in the courtroom and the teacher in the classroom. They are professionals. When a student asks a question, the teacher in the classroom doesn't say, "I'll have to go and ask my boss before I let you know the answer." The teacher has power by virtue of the fact that he is a professional.

This is how I conceive of the members of the corporation. The long-term future of a corporation depends upon its professionals just as surely as your survival depends upon the professional in the emergency room. Decisions have to be made where the knowledge is. So I believe professionals should have rights within the organization. Indeed, I believe they require rights to do their jobs. So you see, I am only talking about membership as a requirement for those upon whom the corporation's future depends. Those people--by virtue of their professionalism--are at the heart of the high-commitment organization. Other workers need not be members. I am not talking about Machine Age organizations. I am talking about something new.

S&B:You mention a high-level of commitment. Does that mean lifetime employment in your model?

Charles Handy: No. I believe in membership and a high level of commitment, but not necessarily forever. The British Army offers an example I like. It is an organization with terrific commitment, both ways. But it's not forever. The Army says to a young person, "We want you, but only for 15 years." The Army needs a few wise old owls with lots of experience. But it doesn't need that many. What it needs are highly trained, bright young people. And it needs to keep its overall age down. I mean you couldn't have a bunch of old men storming the beach, could you? You would have nothing but heart attacks.

Charles Handy: No. I believe in membership and a high level of commitment, but not necessarily forever. The British Army offers an example I like. It is an organization with terrific commitment, both ways. But it's not forever. The Army says to a young person, "We want you, but only for 15 years." The Army needs a few wise old owls with lots of experience. But it doesn't need that many. What it needs are highly trained, bright young people. And it needs to keep its overall age down. I mean you couldn't have a bunch of old men storming the beach, could you? You would have nothing but heart attacks.

So the Army says it will start out offering a new recruit a seven-year contract. It also says, "We'll train you so you'll be more valuable when you leave." After seven years, the Army can offer you another contract for 10 years or so. But it is the Army's decision alone to offer you a subsequent contract, which you may or may not accept.

Now the Army doesn't offer that contract to everyone. It assesses its needs and winnows out those people it no longer requires. It does this, offering contracts to fewer and fewer people, to keep itself young, and with the right number of generals and so on. But here is the point. In that context it is perfectly permissible--and there is no social stigma--to be a former junior officer who has retired at 32 years old. Nor is there a stigma to have retired as a major or a colonel when only 44 years old. In fact, it works the other way. Retired Army personnel have skills that are desired in other settings.

S&B:So commitment is not necessarily a lifetime offer.

Charles Handy: Precisely. The Army is a high-commitment, learning organization. But the expectation of most of its members is not for lifetime employment. They have predictable points of decision and no social penalties if their contracts are not renewed. And when members of the Army are not going to be offered new contracts, they know it well in advance and have plenty of time to prepare. So the British Army gets what it needs for as long as it needs it and there is a nearly total commitment from the soldiers during that time.

S&B:How would this apply outside the military?

Charles Handy: Is it very different in investment banking? If you run a bank, you know that you need traders of a certain sort. They have to be street wise but not necessarily wise in other ways. They need to be young and without much need for sleep. They need to be driven by money and have quantitative minds, and so on. And they're probably best if they're under 30 years of age.

I think you would be foolish to give someone like that anything like the expectation that they would move from being a trader to being a general manager of the investment bank. So why not give the good traders 10-year contracts and make sure they have a bloody good rise, lots of money and then let them move onto something else. Just don't tell them at 29 years old they have to leave at 30. That would be cruel. But why not design for total commitment, but with the recognition that you are not responsible for your traders for the rest of their lives? This is something especially suited to the future and to today's far-flung organizations.

S&B:Why is this important for today's global companies?

Charles Handy: It's very natural. With people scattered around the world, you really have to let them be on their own. The assignments are often difficult and you need them for specific purposes. Those purposes may change. That means you have to run the organization on the basis of professionalism and trust--subsidiarity. If you run an organization like that, you really have to base it around relatively small, long-term, continuing units where each member has a high level of commitment. Now you may have all kinds of stringers too, but at the core there must be a community of trust, which is the membership community. You let the Brits run Britain, the Germans run Germany, and the Japanese run Japan--with as little meddling as possible. The young Silicon Valley companies are learning this. But at the heart, there must be the mutual bonds of commitment.

S&B:Aren't you simply advocating decentralization?

Charles Handy: Yes and no. What I am really talking about is the Federal model of organizations and about building high-commitment, professional organizations. You see, the really interesting thing about Federalism is not its decentralization. It is actually much more complicated than that. Yes, it is decentralized when the local pressures are important. But it is also centralized whenever that works to the benefit of all.

So for instance, Unilever used to manufacture soap powders in every European country. And it marketed them in every European country. In a sense this was total decentralization. But of course, once soap powders became a commodity, where price mattered far more than anything else, it became rather ridiculous to be so decentralized. They were sacrificing economies of scale. So they now actually manufacture soap powders in the center of Europe--in one place--which seems to me an appropriate use of centralization. The problem, of course, is deciding which goes where.

S&B:How does a manager make those decisions?

Charles Handy: The process is important because the principle of Federalism is that this must be a contractual negotiation or agreement between the parties. Between--as you might say--the barons who are in the countries or regions and the center. You see, if the center tries to impose its solution on the barons, they will resist it. The process is important because it is only when you get the barons to say, "Yes, it is sensible for us not to do our own manufacturing," that you will get the things running smoothly. So the process has to be one of negotiation and the savings from centralizing have to be distributed fairly, for the benefit of the organization as a whole, and not just to the center.

S&B:With all the negotiations you talk about, isn't this a very slow way to run an organization in today's rapidly changing world?

Charles Handy: People would argue that it is a very cumbersome and time-consuming decision-making process and that the world is moving incredibly fast. So how can a federation keep up with the pace of change? My answer is to look at the United States. If the pace of change becomes such that the whole federation is threatened, as in a large-scale war, the power of the center increases.

But the opposite is also true. Now that it appears that the United States is not going to be fighting any massive wars, the power of the center is waning and the power of the periphery--the states--is increasing. You simply do not need a massive central government at all times in a Federal constitution.

The same is true in business. If there is an all-out war--if Motorola is going to fight for its very existence, for example--then you will see power going to the center. If it is a matter of survival, you will not see centralization resisted by the barons because they understand that their own survival is threatened too, and that they will need to mobilize resources very quickly. If, on the other hand, that kind of rapid change is not required--if the issues are those of opening new markets, developing new products, getting into China, whatever--then the Federal model says, "You should decentralize power because moving into the future is going to require a set of diverse responses." If the change is one of threat, Federalism collapses into an oligarchy. If the challenge is one of variety, Federalism goes the other way. Typically, people don't think about this. It just sort of happens to them.

S&B:So setting up as a Federal corporation gives you the ability to respond more appropriately?

Charles Handy: I think so. I believe that what typically happens is that we react intuitively and then people like me come along afterwards and explain it. I like to say that life is understood backward, but unfortunately it has to be lived forward.

S&B:So you put Federalism at the heart of the post-Machine Age organization.

Charles Handy: Well, yes, as a conceptual model. The value of the model is that it tells you what is happening. It helps to have a model that says if the problem is one of innovation, and if you centralize to respond to it, you are probably doing the wrong thing.

S&B:What is the role of the corporate center in the Federalist model?

Charles Handy: Ah yes, the corporate center. In my Federalist model, the center does not run the corporation except in times of war or its equivalent.

S&B:So what exactly does the corporate center do to add value?

Charles Handy: The corporate center is not in charge of the operation unless the organization is under direct threat. You see, in normal times, the job I give to the corporate center is to be what I call, "in charge of the future." It means keeping an eye on the competition, on new markets and on strategy.

The organization's overall architecture and design are also the center's responsibilities. That means that the center can move some key people from one operating unit to another, if need be, for the good of the whole. If China is important, long term, you can't expect China to be able to generate everything on its own, straight-away. The center would move people and resources there.

If the center is in charge of the overall future, some of the money from the operating divisions must also be used to invest in the future. The center guides those investments. And, when it comes to marshaling the corporation's overall forces, including its financial resources, the center is in charge of that. Those are some of the ways it adds value.

S&B:You don't need a large staff to do that, do you?

Charles Handy: Oh no. If you have a global corporation, having about 100 people at the center sounds about right. Boots, the big British drug and chemical company, went so far as to build its corporate headquarters so it can't possibly hold more than 100 people. Now that's a statement. The company wants its core to be restricted to very broad oversight. Its job is to make certain that the lights in the cockpit are all green and all agreeing. If they are red, the center sends somebody out to have a look. And of course, the center keeps track of all the money, does planning and so on. It's responsible for the future.

S&B:Is the center concerned with the financial markets?

Charles Handy: That depends upon the kind of federation you are. If you are an American corporation, you would probably raise your capital in America because it's easier. You might also do that if you are headquartered somewhere else. There are a lot of different scenarios.

S&B:And what about monitoring performance?

Charles Handy: Yes, that's part of what the corporate center should do, but only in very broad terms. At Asea Brown Boveri, the big Swiss-based power generation company, the center monitors something like 18 or 20 numbers that are delivered from the operating units every month. These would be money numbers, sales numbers, satisfaction and quality numbers and so on. The center has a kind of multiple scorecard, with target zones for those numbers. That's enough information to illuminate the warning lights.

There is something else the center does that is important and that adds value. The center has the task of building the commitment of the whole federation. Percy Barnevik, chairman of ABB, says that one of his major jobs is not taking decisions, but meeting with key executives and putting on seminars about the future. That's an educational mission. Another chief executive of a Federal corporation said to me that his job is to be a missionary and to go around and say, "You know, this is what we stand for. These are our values." He's a kind of diplomat.

S&B:How else does the core add value?

Charles Handy: There's a British company called Unipower which makes spare parts for automobiles. Unipower is a Federal corporation and has even introduced a new sort of language. There are the operating divisions and then there are the functions--marketing, finance, research and development and so on. They renamed the functions the faculties and renamed the center--where the functions reside--the campus. The idea is that the faculties are the company's reservoirs of wisdom and knowledge and expertise. But they have no real power, only influence. People from the operating divisions are rotated through the faculties for two-year stints. What this does is maintain and spread the faculties' intellectual capital. What I am saying is that a Federal organization is not a command and control organization. It is a learning organization. That is another important role for the center.

S&B:Are there size limits for Federalist companies?

Charles Handy: Do you mean how do you get to be big? In the Federalist model you do so by combining communities of trust for certain purposes, which have to be negotiated and agreed upon. You form constellations. Federalism is a negotiated, contractual arrangement between individual groups. The individual groups can be quite small, flexible and independent, yet the overall organization can be quite huge. ABB is really a federation of something like 5,000 business units. Royal Dutch Shell is a huge company with 120,000 employees operating in nearly every country. It is a federation.

But why would you want to be huge? I once sat up on stage with a C.E.O. in front of the senior members of his company. The C.E.O. said his goal was to create the world's largest organization. He wanted to grow at a truly astronomical rate. I said to him that the two largest organizations in the world today are the Red Army in China and the British National Health Service. And I asked him whether either of those two models was what he had in mind. He was rather embarrassed. Suddenly, growth for its own sake seemed to be a very funny notion.

Twenty-five years ago, I was at a large, international high-tech company headquartered in the United States. I looked at a chart that showed the company's rate of growth versus the rate of growth of the G.D.P. of the United States. By 1993, the C.E.O. said--with a straight face, mind you--that the revenue of his company would cross the line of the United States. He actually said his company's revenues would be larger than the G.D.P. of the United States. Now that was absurd. But he showed it to me on the chart. Of course, it didn't happen. You see, it is not about size.

S&B:What is it about?

Charles Handy: I think it is about commitment, flexibility and effectiveness. I think it is about mutual responsibility and rights. I think it is about membership. It is not about size. The British Army is an amazingly wonderful example of how you can maintain a high-quality organization and actually get smaller. At the end of World War II, Britain had a huge Army. Everybody had to do two years of service. Then in 1955, 10 years after the end of the war, we decided to turn it into a relatively small professional Army. Today, the Army has a fighting force of only about 60,000--that's smaller than Royal Dutch Shell, to make a comparison, and far smaller than just after the war. But the Army does an amazing job. It is very effective, highly trained and efficient. It employs all sorts of sophisticated high-tech equipment. It's also cheaper. It has really reengineered itself since the end of the war. The British Army is a true high-commitment organization. That's what I think it's all about. It's not about size. ![]()

Photograph by Elizabeth Handy

Reprint No. 95405

| Authors

Joel Kurtzman, Joel Kurtzman is editor-in-chief of Strategy+Business. |