The wisdom of Charles Handy

In his new book, the renowned business thinker and philosopher passes on his experiences of life, work, and how not to fall into the management trap.

A version of this article appeared in the Winter 2019 issue of strategy+business.

In 21 Letters on Life and Its Challenges, Charles Handy, 87, is talking to his four grandchildren. His goal is to help them as they are “contemplating life’s rich choices.” In a life that he acknowledges has seen technology transform lives in unpredictable ways, he focuses on the question that never changes: what it means to be truly human.

Handy has had a series of different careers, starting out as an executive of the Shell Corporation in Asia. He then taught at MIT and the London Business School and regularly presented “Thought for the Day” on a popular BBC morning radio program. He describes himself as a writer; others might say philosopher and guru.

This edited excerpt from his book looks at what people should want and get out of work, why management is a misleading term, and why the world’s big corporations may not be set up to attract and keep the next generation of talent unless they understand people are not simply a human resource.

Keep it small

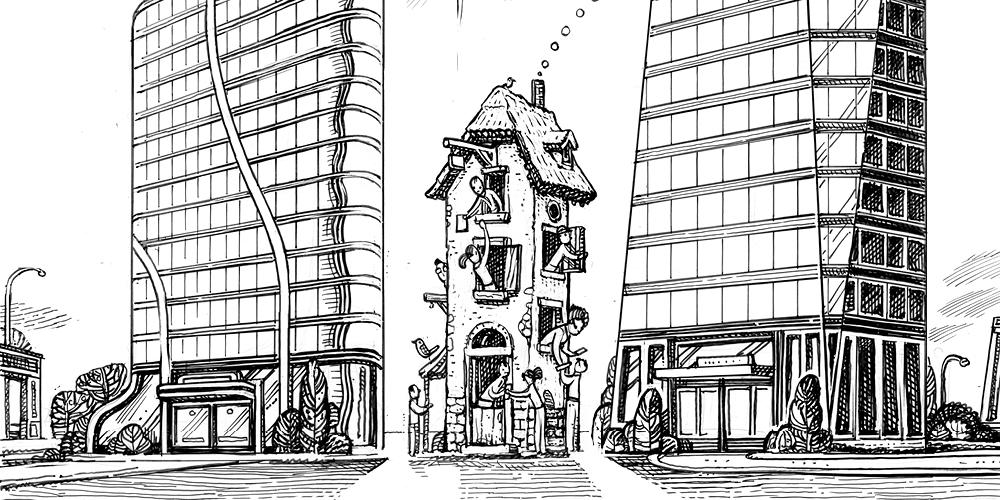

In 1973 Ernst Schumacher, a British/Swiss economist, wrote a book called Small Is Beautiful. The title was the inspired suggestion of an editor, although the main thrust of the book was contained in its subtitle: Economics as if People Mattered. I was tempted to steal that subtitle for my own book three years later because that was at the heart of what my message was going to be. I came to realize that if people truly mattered, then it was better that they worked, if at all possible, in situations where everyone could know each other. For how can you trust or rely on someone whom you never meet? Humans need human-sized groups to be at their best. Small is better, if not essential, to get the job done properly.

I was largely influenced by my own experience. I spent the first seven years of my working life in a subsidiary of the big Shell company, first in Singapore and then Malaysia. It was a work family. We all knew each other like a real family. I then returned to London, to a job in the headquarters of the Shell group [Royal Dutch Shell PLC]. I shared an office with Gerry, with a nice view of the Thames. Gerry was the only person that I got to know at all well. Everyone else was an official of the business. We didn’t wear uniforms in Shell, although there was an unspoken dress code of grey suits and ties, suitably anonymous. We also concealed our private selves behind our job titles. The door of our office had a big brass plate on the outside with the official name of our little department, MKR/35. When we wrote memos, they had to be from MKR/35, not from Gerry or Charles. Gerry did not seem to mind. I did. I was no longer in a family of companions but in a complicated network of boxes called an organization, a machine for organizing work. I did not enjoy being part of a machine.

The good news today is that many of those jobs no longer exist. The new technology does it all. In theory humans aren’t needed. Nobody should regret that. You would never have enjoyed the job that I had any more than I did. Nevertheless, large organizations will still continue to exist in some form, and that poses a challenge. Humans should only be used to do what humans do best: coming together to get things done as sensibly and creatively and effectively as possible. The technology should not try to do what humans do better, and vice versa. We combine best in families, even when we disagree, and in villages of families. Great cities are collections of villages that in turn are collections of families.

Human scale

Why are villages and platoons better than mass organizations? Because they are human scale: They allow you to be a person, not a cog. Professor Robin Dunbar has studied a wide range of human groups down the ages, from early society to the modern day. He has come up with the Dunbar number: 150. This, he says, is the largest “number of people we [can] know personally, whom we can trust, whom we feel some emotional affinity for.... It has been 150 for as long as we have been a species.”

Humans should only be used to do what humans do best: coming together to get things done as sensibly and creatively and effectively as possible.

In my experience, 150 is pushing it. I like the bit of Dunbar’s research where he says that our levels of intimacy go up in multiples of three. We may have just five people whom we know intimately and trust implicitly: our best friends. At the next levels, there are 15 good friends or mates whom we are always delighted to be with, 45 whom we see occasionally, perhaps work with, and 135 that make up our Christmas card or Facebook list of friends.

I have found that for me, 45 works best as the maximum size of a work group. And when a manager tells me that the organization has grown to 100 people, I say, “Be careful. You will now start to introduce specializations and departments; you will become more bureaucratic, a machine.”

We need large organizations — now more than ever, as the world increasingly becomes one big marketplace. Oil companies such as Shell, car manufacturers, pharmaceutical businesses, steelworks, and many others like them have to employ a lot of people to get the work done. The new giants such as Facebook only work if everyone signs up to them, so they swallow up competitors as soon as they appear. The winner takes all. Big, I’m afraid, is here to stay.

Can these city-like organizations restructure themselves into collections of villages that are linked together by the new information technology? My guess is that the organizations will have to start doing just that if they want to attract the best and brightest of the new generation. Already young people are turning away from the traditional pyramid organizations in which you clamber your way up the hierarchy over the years. The world of work is increasingly going to realize that small is better.

The federal principle

Such organizations already exist. Small startups keep things small, until they become successful. But large organizations are also trying. Haier, in China, employs more than 70,000 people. It makes things, physical things like refrigerators, ovens, domestic equipment, things that might seem ripe for industrial-style mass organization. But Haier is largely made up of 2,000 autonomous groups. These groups of seven to 10 people organize their own work, and if they can make improvements or boost their sales, they can keep some of the savings or profit.

I am a great believer in the federal principle as the best way for all organizations, business as well as political, to grow big while keeping their bits small. Federalism does not mean centralization, but the reverse. Its dominating principle is subsidiarity, an ugly term that effectively means reverse delegation — in that power is considered to lie in the small parts of the organization, which then delegate to the center only the things that the center can do better for them all. It is the only way that a city of small villages can work.

Young people today often start off their working lives in an organization, be it in business, government, or the charity sector. That is sensible, for a time. I see such organizations as the graduate schools for work. They introduce young people to the necessary disciplines of work, the routines and systems, the need to sell as well as produce, the numbers that matter, and the people who can be relied upon. If the organization does not provide the intimacy of a small group and space to use your initiative to make a difference, you should move on, having finished your graduate apprenticeship. Humans are not meant to be machines.

You are not a human resource

Organizations can be tough places. I do remember that when I was offered a job by Shell after leaving university, I sent a telegram to my parents in Ireland saying “Life is solved.” I really thought it was, because Shell had assumed that I would spend all my working life with them; they would see to it that I got paid, did useful work, and would continue to be paid after I retired. There was nothing left to worry about.

That was until I married. When they wanted to post me to Liberia in West Africa, I saw it as one more step in the ladder of promotion. My wife saw it differently. She said, “I did not realize that I was marrying a man who would go wherever he was told to go, would do whatever they wanted.” That was the first time I realized I had made what I was later to call a pact with the devil. In exchange for the promise of financial security and guaranteed work, I had sold my time to complete strangers with my permission for them to use that time for their own purposes, those purposes being partly, or even mainly in some cases, to enrich their investors. I had thought they were giving me something, ignoring that I had in effect given away my birthright, or my right to do what I wanted with my own life.

Of course, most organizations do not see it that way. They see it as a consensual arrangement from which both sides gain. Some lean over backward to make their place of work more user-friendly, with fringe benefits ranging from free food, healthcare, and childcare, to meditation classes, sports facilities, and community volunteer opportunities — all a well-intentioned attempt to provide a whole-of-life environment. You will still have given the organization the right to use your time as they see fit. The effective use of that time is what is then called “management.”

Think about this: Any organization whose key assets are talented or skilled people — universities, theaters, law firms, churches — don’t use the word manager to describe the people in charge. They call them deans, senior partners, bishops, directors, or team leaders. [In those organizations,] the title of manager is only used for those who are in charge of things, not people, that is, the physical or inanimate parts of the organization: the transport, the information systems, the building. Instinctively these organizations recognize that people don’t like to be “managed,” and they avoid the word wherever possible. The word implies that you are a resource, something that is controlled by others, a thing to be used and deployed as others see fit.

The unfortunate term human resources only encourages this way of thinking. As individuals we like to think that we have choices. In signing away our right to our time, we have ceded power over the most active part of our lives to others in the conviction that it is in our interest to do so.

Words do matter

Organizations do need to be organized. The flow of work needs to be compartmentalized and people need to know what they are required to do, by when, and to what standard; but that is managing the work, not the individuals. The difference is crucial. If I know what I am meant to be doing and I believe it to be either useful or necessary, I will do it without someone looking over my shoulder. I remember Mel, a colleague of mine at the London Business School. He specialized in the management of groups and teams. Then one day he left to start his own restaurant. A year later I bumped into him. “It must be nice,” I said, “to be able to practice all that you were preaching back at the school.”

“It’s funny,” he replied, “But I found that if you choose the right people to start with, and if they know what they are meant to do, they just get on with it without any checking or fuss.”

I call that leadership: creating the conditions for good work, choosing the right people and setting them standards of achievement that they can understand, and rewarding them when they meet them. You may say that I am just playing with words — but words describe the world, even the local world of the organization. I now believe that work needs to be organized, that things should be managed, but that people can only be encouraged, inspired, and led. (By things, I mean the buildings, information systems, or anything else physical.)

There are those, however, who prefer to elevate the idea of management to include organizing and leading. Management, said the great Peter Drucker, is a human and social art. Much though I admire the thinking and writings of Drucker, I do wish that he had avoided that word because it has been so misinterpreted and abused by people who see it as an excuse to exercise their power over their fellow humans. Words do matter. They change behavior. They shape our thinking because of the implicit messages they send; then our thoughts shape our actions. Call someone a human resource and it is only one step further to assume that he or she can be treated like other things, be oiled and fueled, perhaps, but also controlled and even dispensed with when surplus to requirements.

Good managers know this, you may say, but language can trick you into behaving in ways you would normally avoid. Words are devious, dangerous things. Always watch your language lest you send messages that you never intended.

One day you may be head of some department in an organization, or it may be your own business or project, because you can’t achieve much by yourself alone. If you are like me you may well feel inadequately equipped for the task you have been given. After a short two years I was put in charge of Shell marketing in Sarawak, a state in Borneo with a population the size of Wales’s and rivers instead of roads. I was on my own with three airfields and two depots. I later discovered that this was the Shell way of grooming its future leaders — throw them in at the deep end of a small outfit where they could not do much harm but might make a difference and would certainly learn a lot.

It worked. I did learn a lot, mostly by making mistakes that I was able to correct before anyone found out. But at first I felt naked and longed for the handbook of so-called management. I now know that there isn’t one. Any that you may come across, including one that I wrote myself, will turn out to be practical common sense dressed up with long words to make it seem professional. I would only urge you to remember the three different activities of organizing, leading, and managing, and to apply them appropriately, because I truly believe that managing people, instead of leading them, is wrong and has resulted in too many dysfunctional and unhappy workplaces. People are more than a human resource.

Author profile:

- Charles Handy is an independent writer, broadcaster, and teacher. His many books include The Empty Raincoat, Gods of Management, and The Future of Work.

- Extracted from 21 Letters on Life and Its Challenges, by Charles Handy, published by Hutchinson on June 27, 2019. Copyright © 2019 by Charles Handy.