Recent Studies

On the perils of stretch goals, modular engineering, educating CEOs, and other topics of interest.

Why Honest Workers Cheat

Maurice E. Schweitzer (schweitzer@wharton.upenn.edu), Lisa Ordóñez (lordonez@u.arizona.edu), and Bambi Douma (bambi.douma@business.umt.edu), “Goal Setting as a Motivator of Unethical Behavior.” Click here.

|

|

Photograph by Opto |

The authors contend that setting specific, quantified targets for employees to reach — such as selling 50 magazine subscriptions a week, or shipping 10,000 PCs a month, or completing $100,000 worth of repairs a quarter — encourages unethical behavior. This is primarily because workers are so desperate to reach these plateaus that some may falsify accounts, overstate sales figures, deliberately ship unfinished products, or perform unnecessary repairs.

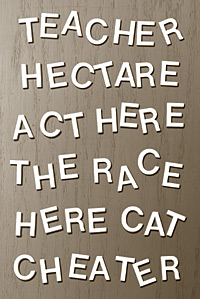

To test their thesis, the authors broke 154 undergraduate students into three groups and asked them to create as many anagrams as they could in one minute from a seven-letter word. This was repeated across seven rounds.

Participants in the first group were instructed simply to do their best. The second group was given a goal of creating nine words in each round; they were told that this was achievable, but were offered no financial incentive to do it. The third group was also presented a target of nine words per round — and group members were told they would earn $2 for each round in which the goal was attained.

Participants in all three groups were asked to check their own work. And those in the third group were also each given an envelope containing $14 from which to take the money they earned. In all cases, anonymity was provided (although researchers were able to match individual workbooks with the three groups).

So did the authors prove their point? To a degree. First the good news: The study found that most people are basically honest, despite being given the opportunity and a motive not to be. Of all the participants, only 10.5 percent in group one and 22.7 percent in group two overstated their performance on at least one occasion. And even in group three, whose participants had a financial incentive to cheat, less than a third (30.2 percent) actually did so.

Of course, these numbers indicate as well that participants with specific goals — that is, group two and group three combined — were more apt to cheat than those without goals, regardless of whether there was financial encouragement. Also, the study found that participants were more likely to overstate their productivity when they were close to reaching their goals than if they missed by a wider margin. For example, participants in groups two and three cheated more often in rounds in which they had created eight valid words — off the target by one — than they did when they were farther away from their goals.

Goal setting, the authors conclude, can adversely influence corporate culture and should be used with caution. When managers set goals, they should be wary of unethical behavior. And they should be especially vigilant when employees approach their targets.

Modularity à la Mode

Carliss Y. Baldwin (cbaldwin@hbs.edu) and Kim B. Clark (kclark@hbs.edu), “Modularity in the Design of Complex Engineering Systems,” Harvard Business School Working Paper No. 04-055. Click here.

The concept of modularity is familiar to anyone who has ever bought a mix-and-match product. When you purchase bedding, for example, you know that the bed frames, mattresses, pillowcases, sheets, and covers from different manufacturers will all fit together because they come in standard sizes. In effect, these are the bedding modules.

Although the use of modules is perhaps best known as a way to make buying product add-ons and peripherals more convenient, a much more complex engineering concept known as modularity-in-design has the potential to change the entire structure of an industry, say Carliss Y. Baldwin, the William L. White Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School, and Kim B. Clark, dean of the faculty at Harvard Business School and the George F. Baker Professor of Administration.

To demonstrate this, Professors Baldwin and Clark point to the U.S. computer industry. Traditional economic theory holds that over time market structures stabilize, and a few dominant players emerge. But this was not so in the computer industry between 1950 and 2002, according to the authors.

Although market value was initially concentrated in a few firms, it is now spread widely but very unevenly among 1,000 firms across 16 subindustries, ranging from manufacture of printed circuit boards to programming services. In 1969, for example, 71 percent of market value was tied up in IBM stock, but by 2002, the largest company, Microsoft, accounted for less than 20 percent of the total industry value.

This unlikely evolution occurred because the PC industry adopted, perhaps unconsciously, the tenets of modularity-in-design. To explain this concept, the authors compare it to two more common forms of modularity. A system of goods is modular-in-use if end-users can mix and match elements to suit their needs — for example, buying bedding or a sectional sofa. And a system is modular-in-production if the components can be produced separately and brought together for final assembly. Automobile manufacturers, for example, have used such systems in mass production for more than a century.

But, the authors argue, the mere fact that a product’s use or manufacturing has been split up and assigned to separate modules does not mean that the design of the system is modular. In fact, these products may depend on systems that are quite centralized — e.g., Intel’s chips can be produced at many separate and independent factories, but they must be made exactly to the company’s rigid specifications. By contrast, a system is modular-in-design when the design process itself is split up and distributed across separate modules that are coordinated only by a set of design rules, but not necessarily by discussions among the designing companies.

A particular strength of modularity-in-design is its ability to accommodate uncertainty. This is because changing the design of an individual module is relatively easy compared to redesigning the entire system. According to Professors Baldwin and Clark, modules may be “changed after the fact and in unforeseen ways as long as the design rules are obeyed.”

Modularity-in-design also encourages experimentation because new and improved module designs can be easily (and relatively cheaply) substituted for older ones without requiring a redesign of the other modules. At the same time, the risk that comes with innovation is reduced because the cost of rejecting a new design for a single module is also relatively low.

“Modularity-in-design,” Professors Baldwin and Clark conclude, “can open the door to an exciting, innovative, but very Darwinian world in which no one really knows which firms or business models will ultimately prevail.”

MBA Pedigrees and CEOs

Aron A. Gottesman (agottesman@pace.edu) and Matthew R. Morey (mmorey@pace.edu), “Does a Better Education Make for Better Managers? An Empirical Examination of CEO Educational Quality and Firm Performance,” June 2004. Click here.

More and more CEOs have MBAs and other graduate degrees from pedigreed universities, a trend that is generally regarded as a good thing. But are better-educated CEOs better CEOs? Aron A. Gottesman, assistant professor of finance at the Lubin School of Business at Pace University in New York, and Matthew R. Morey, an associate professor of finance and undergraduate program chair at the same school, set out to find the answer with the first rigorous study to test the link between CEOs from top schools and firm performance.

The researchers used a twofold definition to characterize the quality of education that chief executives received. First, they considered the CEO’s degree: A graduate credential, such as an MBA, signified a better education than an undergraduate degree. Second, they appraised the standing of the school, which was calculated from the mean SAT or LSAT scores from the middle 50 percent of first-year students or the mean GMAT score of new entrants. The assumption was the more prestigious the school, the higher the entrance requirements.

The researchers then applied these two factors to a sample of 482 CEOs drawn from firms listed on the New York Stock Exchange as of January 1, 2000. To be included, each CEO had to have at least an undergraduate degree from a U.S. institution.

The graduate degrees that CEOs are most likely to have are an MBA or a law degree from some of the best universities in the country, according to the findings. About a third of the CEOs surveyed were MBA graduates, and the mean GMAT score of the participants in their MBA programs was 656.7 out of a possible 800. Some 12 percent of CEOs were law school graduates, from schools whose students had a mean LSAT score of 161.8 out of a possible 180. And just over 10 percent of CEOs held graduate degrees other than an MBA, such as in engineering or psychology.

Professors Gottesman and Morey then correlated CEO education profiles with a risk-adjusted measure of their firm’s performance. They found no evidence that companies run by CEOs from more prestigious schools (undergraduate or graduate) perform better than those led by CEOs from less prestigious schools.

“If anything,” they note, “we find that prestige of the CEO’s school is negatively related to firm performance.” For example, the study found that companies with the lowest return on assets were more likely to be led by CEOs who went to schools where students have the highest average SAT scores.

The study also found that companies run by a CEO with an MBA or law degree were no better off than those led by a CEO without a graduate degree. In fact, firms headed by a CEO without an MBA or law degree performed slightly better.

In Search of Silicon Valley

John Armour (j.armour@cbr.cam.ac.uk) and Douglas J. Cumming (douglas.cumming@unsw.edu.au), “The Legal Road to Replicating Silicon Valley,” Economic and Social Research Council Centre for Business Research, University of Cambridge Working Paper No. 281, March 2004. Click here.

Re-creating the economic and entrepreneurial vigor and success of Silicon Valley elsewhere is a persistent dream of politicians around the world. Unfortunately, governmental intervention is not the answer. Publicly backed venture capital funds have an erratic track record and can actually reduce the overall investment by venture capital and private equity firms. Some are simply poorly conceived and naively managed. And all of them add an extra layer of complexity to the marketplace — particularly by confusing private and public funding.

The government, for example, backed Germany’s first venture capital fund. Astonishingly, fund managers’ compensation was unrelated to the success or failure of their investments, and future funds were guaranteed without reference to the fund’s performance. The performance was poor: an average internal rate of return of minus 25 percent.

So what can governments do to encourage entrepreneurial development? John Armour, a senior research fellow in the Centre for Business Research at the University of Cambridge, and Douglas J. Cumming of the University of New South Wales School of Banking and Finance, say that legislation, not financial support, is the best answer.

Based on research of activities in 15 Western European and North American countries over 13 years (1990–2002), the authors argue that governments should be passing laws that enable and support deep and liquid stock markets. Through IPOs, stock markets offer an attractive exit (usually after three to seven years) for investors and venture capitalists. Without this potentially lucrative payday, startups are less enticing. Helpful legislation, according to the researchers, could include potent disclosure laws, tax incentives for individual investors, and minority shareholder protection.

Generous bankruptcy legislation is another critical element, they write, because it increases the availability of venture capital by effectively lowering risk. In contrast, punitive bankruptcy legislation can discourage would-be entrepreneurs. The logic here is that the period prior to actually obtaining venture capital is the one during which the entrepreneur is most at risk of personal bankruptcy. Businesses are often started on credit-card borrowing. Lessen risk during this period and you may well encourage entrepreneurial activity.

In some countries, the risks associated with bankruptcy are greater. In the United States, no time is required to discharge a bankruptcy. This differs significantly from all the other nations in this research. In Ireland it takes 12 years; in Germany, six. The more stringent the bankruptcy laws, the less likely the next Silicon Valley will emerge.

The European Venture Capital Association’s index, cited in the article, provides a roster of taxation and legal conditions likely to boost

the supply of venture capital. The researchers suggest that creating a fiscal and legal framework in keeping with this index might provide the first step toward a new Valley.

Rebounding from Failure

Mark D. Cannon (mark.d.cannon@vanderbilt.edu) and Amy C. Edmondson (aedmondson@hbs.edu), “Failing to Learn and Learning to Fail (Intelligently): How Great Organizations Put Failure to Work to Improve and Innovate,” Harvard Business School Working Paper No. 04-053. Click here.

In a world fixated on success, failure has become curiously fashionable. Witness the deluge of commentary on — and unflagging interest in — dramatic corporate failures, such as Enron and Parmalat, as well as the success of Sydney Finkelstein’s book, Why Smart Executives Fail: And What You Can Learn from Their Mistakes (Portfolio, 2003). Add to these explorations of failure a paper by Mark D. Cannon, assistant professor of educational leadership at Vanderbilt University, and Amy C. Edmondson, a professor at Harvard Business School.

Failure — defined in the paper as “deviation from expected and desired results” — is a fact of life and of business life. Being able to learn from failure, however, is the real challenge.

Professors Cannon and Edmondson point out that analysis of failures in organizations is never easy because of technical and social barriers. Technical obstacles include the lack in most organizations of the diagnostic, analytical, and statistical skills required to understand the full genesis and ramifications of the failure. Social obstacles are well documented (by Harvard University’s Chris Argyris, among others). People and organizations are uncomfortable with failure. Without a willingness to acknowledge mistakes and personal limitations, learning from failure is unlikely.

Learning from failure, say the authors, is a process that requires identifying it as it first occurs. This is difficult for many organizations, because small failures tend to be ignored or simply accepted. Often these apparently unimportant failures are warning signs of bigger disasters ahead. If a failure is not identified, it may escalate. For example, in the Columbia space shuttle accident, NASA managers initially played down the likelihood that dislodged foam from the spacecraft hitting the left side of the shuttle at powerful speeds contributed to the disaster. The breakaway foam was regarded as commonplace, a normal hiccup in a complex operation, rather than as the starting point of a calamity.

In the corporate world, Mattel’s ill-fated purchase of the Learning Company led to a $105 million loss in the third quarter of 1999, rather than the anticipated $50 million profit. Jill Barad, Mattel’s CEO at the time, overlooked the severity of the Learning Company’s existing problems when the acquisition was made and subsequently did not acknowledge the financial disappointment of the combined companies as a sign that the deal was a mistake. Instead, she remained optimistic and predicted a quick return to profitability. A similar pattern was repeated in the following two quarters.

Why do people and organizations tend to shy away from deep analysis of failures? Because discussing and examining failure requires a spirit of inquiry, openness, and patience, as well as a tolerance for ambiguity. It also demands time to reflect and a dogged persistence.

Professors Cannon and Edmondson argue that learning from failure is an invaluable skill that is worth cultivating in people and their organizations. Failure can be used to drive experimentation if employees are encouraged to try out new ideas and concepts, as long as they are also protected. It is fine to say “fail often in order to succeed sooner,” as the innovation design company IDEO exhorts its people to do. But safety nets must be in place to assure people it’s okay if a project does not turn out as planned. For instance, according to the authors, PSS/World Medical, a distributor of medical supplies and equipment, has a “soft landing” policy; if someone leads an experiment that does not work out, they can have their previous job back.

Lost in Translation?

Sanford M. Jacoby (sanford.jacoby@anderson.ucla.edu), Emily M. Nason (emily.nason@anderson.ucla.edu), and Kazuro Saguchi (saguchi@e.u-tokyo.ac.jp), “Corporate Organization in Japan and the United States: Is There Evidence of Convergence?” July 2004. Click here.

At the beginning of the 1980s, American corporations began to look to the East for organizational inspiration. Japanese corporations appeared to offer a brave new world of efficiency combined with stellar financial performance. The Japanese, of course, were already in the habit of examining American corporate organization, performance, and management in their quest for improvement. With so much mutual interest between Japan and the United States, it’s natural to wonder whether the two nations’ approaches to corporate organization have grown more alike.

To answer this, Sanford M. Jacoby, the Howard Noble Professor of Management and the Area Chair of Human Resources and Organizational Behavior at the UCLA Anderson School of Management; his colleague Emily M. Nason; and Kazuro Saguchi of the University of Tokyo Economics Department conducted surveys of human resources (HR) executives in 374 large companies in Japan and the U.S.

Both models, they discovered, have changed.

Two decades ago, the differences in Western and Eastern corporate models were crystal clear. At that time, Japanese companies tended to have powerful HR units; on average Japanese headquarters HR departments were twice the size of their U.S. counterparts. The standard Japanese company regarded employees as assets and emphasized long-term employment.

The American model, in contrast, was shareholder oriented and, in terms of employment, market oriented. Seen as a means of minimizing labor costs, HR was usually subservient to finance. Not surprisingly, labor turnover was higher in the U.S. than in Japan or Europe.

Today, in Japan, employee stock options and independent boards of directors are emerging. There is greater emphasis on shareholders. The dominance of the HR function is being questioned as jobs are outsourced, training and welfare budgets are cut, and the era of lifelong employment has come to an end. Headquarters HR units in Japan are getting smaller (down by 22 percent between 1996 and 2001). The finance function, which has long been important in the U.S., is becoming increasingly important in Japanese companies.

In the U.S., the perceived rise in importance of intellectual capital, corporate culture, and a motivated work force has led to improved status for the HR function: Sixty-five percent of senior American HR executives now report to the CEO. HR departments and employees are frequently seen as a competitive advantage rather than a cost.

Still, with all of these changes, the authors note that the difference in fundamental philosophy between U.S. and Japanese HR executives remains acute. Asked “What is important to you in your job?” Japanese HR directors ranked safeguarding employees’ jobs first; American HR directors listed share price first and job protection seventh (out of nine).![]()

Des Dearlove (des.dearlove@suntopmedia.com) is a business writer based in the U.K. He is the author of a number of management books and a regular contributor to strategy+business and The (London) Times.

Stuart Crainer (stuart.crainer@suntopmedia.com) is a business writer based in the U.K. and a regular contributor to strategy+business. He and Des Dearlove founded Suntop Media, a publishing and training company providing business content for online and print publications.