Correcting a Culture That Breeds Mistakes

Major corporate crises don't just happen. Most are the result of multiple mistakes.

(originally published by Booz & Company)When a corporation finds itself embroiled in a major crisis and spinning out of control, hindsight usually reveals a series of events leading up to the incident. Whatever the cause — a catastrophic environmental accident, a serious product design defect, a major strategic misreading of a market, or something else — major crises don’t just happen. Most are the result of multiple mistakes.

This phenomenon — a chain of events leading to a crisis — has been well documented in physical disasters. Take the accident at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant in 1979. Here a series of procedural mistakes, including judgment errors in performing routine cleaning operations made by incompetent or inattentive operators and system design engineers, led to the core meltdown that ultimately changed the fate of the entire nuclear power industry.

Chains of mistakes often cause colossal operational or strategic missteps in business. Consider the crisis that ensued in 1994 when Intel released a new microprocessor with a design defect. This mistake was followed by denials that a problem existed even after Intel had internally verified that the chip was faulty. Compounding the problem, Intel’s reaction to customer complaints was perceived as condescending, unsympathetic, and bureaucratic. In the two months before Intel authorized a replacement program for the flawed product, the company lost significant market value, and ultimately incurred a $475 million charge for costs associated with the debacle.

Some firms (which also consistently show up on the lists of best-managed companies) are able to avoid such missteps. My research shows them sharing a belief in six precepts, which are embedded in their cultures and management systems. They:

-

Create a system to detect patterns of mistakes early and trust the data.

-

Communicate and seek candid advice throughout the organization and from trusted outsiders.

-

Don’t underestimate potential damage of mistakes.

-

Consider the unthinkable.

-

Protect the relationship with customers at all costs.

-

Are not passive; a bad situation will never go away on its own.

Most, not surprisingly, are blue-chip successes, among them Johnson & Johnson, IBM, Dell, McDonald’s, Southwest Airlines, and Toyota.

Such companies have made big mistakes, but they make fewer of them, discover them earlier, and fix them more adeptly and aggressively than other organizations.

Johnson & Johnson’s reaction to the Tylenol tampering incident more than 20 years ago is still the most frequently cited example of excellent crisis management. The company’s national recall was not necessary, given the assessment that the problem was local to Chicago. But Johnson & Johnson’s famous credo, with its emphasis on consumer safety, guided decision makers. In contrast, advocating for customer welfare did not appear to be a strong cultural value guiding Intel’s response to its microprocessor crisis.

Many other well-known organizations have failed to appreciate the effects of multiple mistakes and paid dearly and publicly for it.

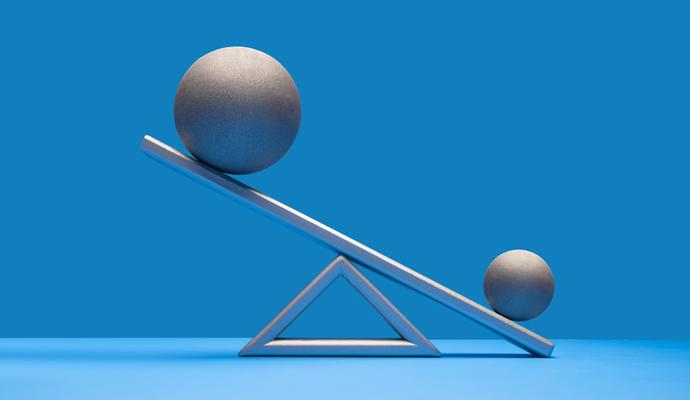

The specific high-profile mistakes were all different — accounting illegalities (Enron and HealthSouth), strategic market blunders (Kodak), design flaws that compromised customer safety (Ford and Firestone). But the cultural factors that so obviously influenced leaders’ behavior were the same:

-

Myopia. “We’ve always done everything right, and those market changes you see are not real.”

-

Hubris. “We deserve to be rewarded for being so much smarter and better than our competitors; they can’t even understand what

we do.” -

Egocentricity. “We’ll ask when we want employees’ ideas. Do your job and don’t speak up because your more experienced superiors know better.”

Today, no company can afford these cultural excesses. The ability to listen, learn, take risks, and manage mistakes must be part of every manager’s repertoire. Mistakes happen, but they can be caught more quickly if companies detect problems before they multiply — and then truly learn from them.![]()

Robert E. Mittelstaedt Jr. (robert.mittelstaedt@asu.edu) is dean of the W.P. Carey School of Business at Arizona State University and author of Will Your Next Mistake Be Fatal? Avoiding the Chain of Mistakes That Can Destroy Your Organization (Wharton School Publishing, 2004). He served as a nuclear submarine officer for five years and was a professor at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania for 30 years.