Don’t fight regulation. Reprogram it.

Business and government should regard the rules as an operating system: a platform, updated collaboratively, that encourages innovation and the common good.

It’s significant when an entrepreneurial leader argues for more engagement with government — especially when it’s Microsoft cofounder Bill Gates, one of the most influential people in the history of the computer and software industry. In a February 2018 interview, the technologist-turned-philanthropist asserted that tech companies may be too adversarial to their regulators. Gates warned firms to avoid “advocating things that would prevent government from being able to, under appropriate review, perform the type of functions that we’ve come to count on.”

The inventor of the world’s most popular PC operating system is onto something. Gates sees his contemporaries paying the price for their entrenched opposition to public-sector scrutiny. But while Gates has identified the problem, the solution requires stepping back and looking more objectively at the relationship between business and regulation. Company leaders should think of government regulation as an operating system — a structure that determines how well they function. Rather than seeing regulation as a constraint on innovation and entrepreneurship, they should think of their government-relations strategy as writing better code.

The operating system of your computer or smartphone — whether it’s Windows, iOS, Android, Linux, or something else — is the foundation on which your favorite apps sit. It is the embedded set of code that enables and regulates the capabilities of the applications. You probably take it for granted, because you rarely interact with it directly. Although it operates behind the scenes, the operating system is also a consistent source of public interest. Tech executives stage grand unveilings in auditoriums packed with developers and fans for new releases. These leaders recognize how important it is to be attuned to the latest and greatest operating system architecture because it serves as a platform and toolkit for innovation.

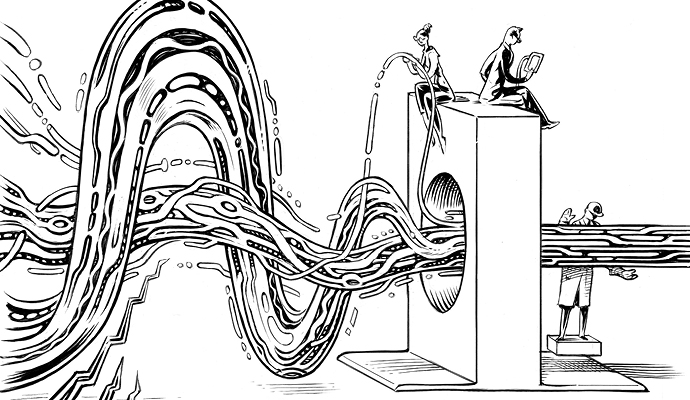

Now imagine a company as the equivalent of an app. What is its operating system? What regulates its capabilities and interactions? Like it or not, the answer is the government — not just policy, but the way that policy is implemented and designed.

Businesspeople too often assume that the relationship between government and the private sector is (and should be) adversarial. They imagine two opposing forces, each setting their bounds of control. But if you can envision government and business as platforms that interact with one other, it becomes apparent why the word code applies to both technology and law. A successful business leader works with regulation the way a successful app developer works with another company’s operating system: testing it, providing innovative ways to get results within the system’s constraints, and offering guidance, where possible, to help make the system more efficient, more fair, and more valuable to end-users.

Like the computer language of an operating system, legal and regulatory codes follow rules designed to make them widely recognizable to those who are appropriately trained. As legislators, regulators, and other officials write that code, they seek input from stakeholders through hearings and public-comment filings on proposed rules. Policymakers rely on constituents, public filings, and response analysis the way software designers use beta testers, crash reports, and developer feedback — to debug and validate code before deploying it across the entire system.

Unfortunately, policymakers and business leaders don’t always embrace what software developers know about collaborative innovation. Think about how much less a smartphone could do if its manufacturers never worked closely with people outside of their engineering department. When only a small subset of voices are involved, the final code only reflects the needs of the most vocal groups. As a result, the unengaged are stuck with a system that doesn’t take into account their needs, or worse, disables their product.

Policymakers may also benefit by emulating the kind of interoperability that makes software effective. When enterprise systems are too different from each other, people struggle with system unfamiliarity. They also run into interoperability issues when trying to function across multiple systems. A product development team can devote massive amounts of resources to designing and building something to work perfectly in one operating system domain, only to have it slow down or completely freeze in another.

These are the same issues that businesses face when crossing political borders. The barrier doesn’t have to be as wide as an ocean; even moving from one city to another can raise interoperability concerns. Confronting the legal codes of a new country or jurisdiction is like working with a new operating system; it introduces bugs that must be addressed for a consistent customer experience. Different jurisdictions with different sets of code create more complexity, and demand that the “policy engineers” within each company develop awareness and fluency in each region to make the product a success.

Thinking Like a Coder

Some business leaders react to regulatory constraints by acquiescing. They find ways to make money through ingrained practices that internalize the rules. They become complacent and risk averse. Other business leaders ignore rules that don’t seem to apply to them, and don’t realize that they overstepped until they are charged. This can cause trouble, as CEOs find out firsthand that (for example) their companies are brought up on antitrust charges.

We anticipate the day when policymakers and industry leaders “sprint and scrum” together on new regulations.

If you can adopt the same attitude that a software company holds toward an operating system, then you realize these obstacles are manageable. With the right policy strategy and strong allies, you can fulfill the objectives of the regulator while still fostering a thriving business. Just as the collaborative standards bodies continue to develop Bluetooth, USB, and Internet protocol (IP), businesses can motivate public officials to unite and codify agreements that streamline unnecessary complexity instead of burdening enterprises with intricate differences.

For policymakers in government, thinking of regulatory practices as an operating system may be the best way to keep pace with rapid geopolitical and technological change. This will make regulatory code less onerous and more effective. Officials can move in the right direction by updating the code more frequently: putting out new policies that represent the changing values of their constituents, reversing the old design, and forcing common systems to splinter. This can also help maintain some of the intention of the original code. For instance, agreements such as NAFTA and organizations such as the European Union were intended to make life easier for business. After the Brexit vote and the rise of nationalism in other parts of Europe, new adjustments to the code may emerge, as government leaders rethink their early ideals and try to hold the Union together.

Business leaders, for their part, can adopt a philosophy of trusted tech: ensuring that societal concerns are kept in mind when they bring cutting-edge products to market. Ideally, that will involve a self-regulating “lead-by-example” approach to earn the trust of public officials and set the bar for competitors. Then, mindful of constant disruptive changes, they can make their policy engineers more available to get closely involved in the code-writing process.

We anticipate the day when policymakers and industry leaders “sprint and scrum” together on new regulations, establishing consensus-driven collectives to develop new policies that participants can monitor and enforce. Business should evaluate these options to see if they are feasible alternatives to the traditional policymaking process. At the same time, public officials should identify corporate actions that they believe are not in the public interest and design incentives that discourage these practices.

Getting there may not be as difficult as it seems. When Bill Gates advocated for cooperation, his words reflected his long-standing personal experience. There is great value for both government and business in learning to strategically leverage regulatory frameworks as viable operating systems that foster innovation and competition while promoting the greater good.

For further insights, read PwC’s 2018 State of Compliance Study.

Author profiles:

- Alison Kutler is the leader of the strategic policy advisors practice at PwC US, based in DC. Previously, she served as chief of the Consumer and Governmental Affairs Bureau at the U.S. Federal Communications Commission.

- Antonio Sweet is a senior strategic policy advisor with PwC US, based in DC. Previously, he served as policy advisor to the chief technologist of the U.S. Federal Communications Commission and earned his degree in electrical engineering from Harvard University.