Ecosystems for the rest of us

Before companies can benefit from collaborations, they must be clear about their role.

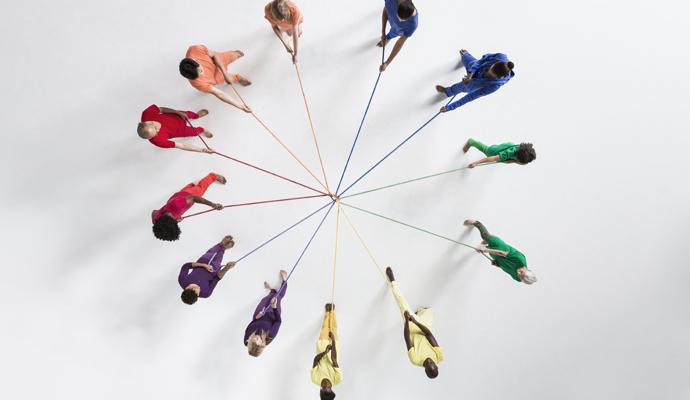

Digitally enabled ecosystems are a vital part of the modern business landscape. They open the door to new customers and markets, and broaden and enhance a firm’s value proposition through the seamless bundling and integration of goods and services. Last but not least, ecosystems help companies become more innovative. It’s little wonder so many want to get involved.

Yet despite all the justified excitement over ecosystems, many companies are still feeling their way around an ecosystem strategy. Lacking experience, they often make poor decisions about which role they should play. Too often, they assume they should be in the driver’s seat as an ecosystem orchestrator but underestimate the time and resources needed to manage their partners. Or they focus on building a solution that is feasible but not desirable to either customers or partners. In their blithe expectation that everyone will flock to their solutions, they confuse ecosystems with egosystems.

Companies need a better understanding of how ecosystems can further their strategic ambitions. They can get more from the ecosystems they lead—or, more often than not, join—by reexamining the basics of what they want and being more rigorous about upfront choices on how and where to play. To do this, firms must also be clear on why they want to engage with ecosystems.

The goal is a clear ecosystem strategy. Much as firms have corporate and merger-and-acquisition strategies, so should they have a clear strategic vision of why, where, and how they should engage in business ecosystems. We’re now beginning to see that top companies take a portfolio approach to ecosystems—that is, they mix and match their participation depending on the role that best fits their corporate strategy.

This article shares some pointers on how best to leverage ecosystems and avoid making bad decisions.

Where to focus

Multiproduct ecosystems bring together two or more products or services, created by multiple providers, to form a unified value proposition for the customer. Before getting involved in a multiproduct ecosystem, firms need to set or confirm the boundaries and scope of their participation and reflect on how their own product or service might connect to a broader set of customer needs.

Firms can get more from the ecosystems they lead or join by reexamining the basics of what they want and being more rigorous about upfront choices on how and where to play.

Choosing a focus is all about identifying the combinations and configurations that might offer new, compelling value for customers and deciding which products and services in a particular area (known as verticals) it makes sense to get into or stay away from. For example, should a pet food company move into a pet healthcare vertical? Should an insurance company move into health diagnostics and/or wellness?

Once a firm has decided which verticals it should cover, the next question is how it should connect to other members of a multi-actor ecosystem. Should the firm be an orchestrator, a complementor, or a partner? What’s the best position from which the firm can create and capture the most value?

Faced with such a choice, most firms instinctively aspire to be the top dog—that is, the orchestrator of the ecosystem. But while the orchestrator’s role may confer the most authority, autonomy, and control, it’s not necessarily the most appropriate or profitable—and it brings its own costs and risks, too. So it’s important to take a step back and look at all options for participation before making a decision.

When companies consider their role, the question of managerial skill should be foremost. Most companies simply don’t make particularly good orchestrators, since they lack the ability to coordinate a shifting network of firms that collaborate to deliver value. On top of that, orchestration takes time and management resources, and requires a certain level of brand recognition in any market.

When it comes down to it, the roles of complementor or partner may be more appropriate, less time-consuming—and more profitable. Both operate within an ecosystem orchestrated by another company; complementors work at the customer-facing, delivery end of an ecosystem, while partners provide the products or services required to deliver the end product. One example of a complementor is the branded companies that sell products on Amazon. Answering a few questions can help companies avoid making the wrong choices and get trapped in the wrong roles (see “Choosing your ecosystem strategy”).

Choosing your ecosystem strategy

- Build a strong value proposition for the orchestrator, fellow partners/

complementors, and customers. - Make your role indispensable: maximize visibility to the customer.

- Leverage ecosystem governance/

regulations to ensure fair treatment.

- Build strong technological, governance, and relational skills with partners.

- Lock in potential partners that wish to engage with you.

- Double down on a double value proposition for ecosystem participants and final customers.

Senior executives need to ask why they want to engage in ecosystems in the first place. Is it about expanding what the company sells from a single component to an entire solution? Or is it a more opportunistic engagement to allow them to access a new sales channel? Will being involved with an ecosystem increase growth opportunities and help to achieve a higher multiple? Or is it all about supporting innovation? Or a combination of two or more of these things?

A related set of questions focuses on stakeholders. How will customers benefit from the solution that the ecosystem offers? Will the ecosystem create brand excitement through association with other high-profile members? The answers to these questions will help determine the scope of ambition, assess comparative strengths in building a value proposition, and identify what kinds of multi-actor ecosystems offer the best fit.

What it means to be an orchestrator

Orchestrators may get all the glory, but firms that hope to emulate Apple, Google, and Meta risk forgetting about the many organizations that have tried, and failed, to create their own ecosystems. Being an effective orchestrator is tough, and even some top tech firms have lost the orchestrator battle in particular markets. Consider Amazon’s disappointing (thus far) foray into healthcare, or Google, which gave up on gaming by winding down its Stadia platform just three years after announcing its entry into the space.

There are three keys to successful orchestration: capabilities, understanding customer and partner needs (also known as the value proposition), and resources.

Capabilities. Capabilities include both the technical and human resource skills required to manage the ecosystem. Here, a risk for would-be orchestrators is underestimating the difficulty of the task. Just having a dominant market share and a respected brand is not enough, as Nokia painfully discovered through the collapse of Symbian. Although Nokia had a tight grip on the ecosystem, its power merely led it to create an unwieldy number of incompatible phones that didn’t improve the customer experience.

Microsoft also misjudged the intricacies of capabilities and roles, which led to the collapse of its Microsoft Mobile, and GE did too, with its Predix AI.

One error all these firms made was assuming that their dominant position would elicit acceptance from partners and customers alike, when, in fact, they lacked the agility and pragmatism that all effective orchestrators must have to serve their customers. Consider Globe Telecom, in the Philippines, the only telecom thus far to have successfully spawned a unicorn that was a key part of its ecosystem play: GCash. Much of Globe’s success is down to the entrepreneurial, trial-and-error, take-nothing-for-granted approach that its CEO, Ernest Cu, has instituted—and his ability to win the loyalty of retail partners.

We’re now beginning to see that top companies take a portfolio approach to ecosystems—that is, they mix and match their participation depending on the role that best fits their corporate strategy.

Customer needs. Perhaps the most important qualification for an orchestrator is a deep understanding of what its customers and partners want. Indeed, a successful orchestrator must craft a double value proposition—that is, one that appeals strongly both to the end customer and to partners and complementors. The more that sector boundaries dissolve and new opportunities emerge, the more options partners have to choose from—and, in the ecosystem world, loyalty can be a scarce commodity.

For example, the “internet of food” ecosystem space is populated by both startups and diversifying firms. Where are there gaps for new orchestrators? Haier, one of the world’s largest white-goods manufacturers, found its niche by understanding customer needs in different markets. It has gone all in on becoming an ecosystem brand in this space, and it appears to have the resources, skills, and understanding to fine-tune its ecosystem plays, market by market.

In China, for example, Haier engaged in a soup-to-nuts digital infrastructure that allows customers to order, prepare, and cook classic dishes; it had found a gap in the market and used it to unlock a double value proposition linking food producers with Haier’s products. In the US, meanwhile, where Haier owns the GE Appliances brand, it has focused on becoming part of an interoperable internet of things ecosystem for food, in part by engaging with user groups with specific needs, like mushroom growers and amateur chefs. Replicating the solution from the Chinese market in the overcrowded US food distribution market would never work, but GE’s existing competitive position makes Haier’s US ecosystem strategy a smart move.

By contrast, trying to be all things to all people often fails, as it can result in putting together bundles no one wants. A major European insurer, for example, was excited to have purchased a big mortgage marketplace and was also pushing its participation in several other financial businesses. It was motivated by the impressive success stories of China’s Ant Group, one of the most valuable fintechs in the world, and Ping An, another successful insurer turned healthcare and lifestyle orchestrator, and thought its own value-add would be to provide an integrated financial services offering. As the leader of the ecosystem team proudly told me, “Someone could cover all their needs with our products alone!” But the firm hadn’t considered why customers, who appreciated having a choice in the market, would put all their eggs in one basket, and the initiative never got off the ground. Leaders often get excited over the mere possibility of offering a bundle, but there’s little point in doing so if you don’t address a genuine need in the process.

Finding an effective value proposition is particularly important for old-economy firms that are trying to blend the traditional and the innovative, or the physical and the digital. Consider what Majid Al Futtaim (MAF) has done in the Arabian Gulf, where it operates retail properties such as Mall of the Emirates. It has moved beyond offering space to tenants to provide a host of services and experiences to consumers who visit its malls, such as Ski Dubai, a skiable piste housed inside the mall. A loyalty scheme motivates both shoppers and retailers to connect with each other, encouraging store managers to offer compelling, connected value propositions that will entice customers back from shopping online. Through these initiatives, MAF bridges the digitally connected world of consumers and the brick-and-mortar ecosystem of the shopping mall.

Resources. Assuming that firms have the right people and insights to build an ecosystem, there’s still the question of cost—and it can be high, in terms of both money and time. In some markets, it’s feasible to build a “minimum viable ecosystem,” as with Italian company Lavazza’s foray into collaborative ecosystems around the coffee experience. Lavazza is contemplating small investments to enhance its offerings, for example by working with local baristas and coffee aficionados to link Lavazza’s brand to the Italian tradition of taking coffee breaks.

In other markets, however, the investment needs to be greater. Consider Kloeckner, a German steel distributor, which created a digital transaction platform aimed at changing the way steel was bought and sold. This required a significant investment over a decade to first digitize operations and then create an Amazon-style marketplace to sell steel. Even after the digitization part was completed, a significant effort was required to sign up partners to use the system. The company’s share price has been volatile in the recent past, and it’s now about the same as it was when the transformation started, despite the investment in time and money. The digitization was likely necessary, but the platform didn’t add the value expected.

Especially in a period of rapidly rising interest rates, when pursuit of growth at all costs is folly, it’s a mistake to invest in becoming an orchestrator no matter what. The orchestrator must have the time and management resources to build a strong governance framework with its partners and complementors—one that clearly articulates the expectations and benefits for everyone. And it has to be agreed to by all members.

What it means to be a complementor or partner

Most firms should eschew the glamor—and risk—of orchestration and, instead, consider how to become more effective partners or complementors. Companies can adopt a complementor strategy by participating in a number of established ecosystems—either digital or physical—and trying to ride the wave of their success by exploiting their existing customer-facing operations.

It’s all a matter of choosing which ecosystem aligns with the current offering. For example, consider Thrasio, one of the world’s quickest-growing unicorns, which aligned itself with the Amazon ecosystem. Thrasio sought out successful independent sellers on the Amazon platform, then invested in and supported them. It found a role in lubricating the cogs of Amazon’s ecosystem that benefited customers and key stakeholders—the independent retailers. And it did this all under the aegis of Amazon.

What drives strategy for ecosystem partners is not always straightforward. Their options, and potential upside, will depend on the value of their contribution within the ecosystem. They need to ask how important they are to the ecosystem as a whole—that is, their leverage with the orchestrator—to ensure they aren’t taken advantage of. They should also reflect on whether the ecosystem enriches their value proposition for customers. Are they providing a component, technology, or skill that orchestrators need to complete their own offering—like a battery maker for solar panels or a tech firm that can create space in the metaverse? And will they reach more customers—and improve their offerings—by joining the ecosystem?

Sometimes, partners will have to accept that they can’t change the nature of the game to their advantage. It may be that participating in some ecosystems as a partner is a strategic necessity to convey the right impression, or it could be an advertising tool. For example, customers may expect a retailer to be present on different platforms. Indeed, as ecosystems become indispensable distribution channels, multi-homing—i.e., being present in multiple ecosystems—will be an important way for companies with sufficient scale to reach more customers.

Multi-homing offers valuable options to scale up with different partners and strategically limit reliance on a single channel. For example, although a firm may be obliged to retail through Amazon, it may also be worth maintaining a storefront on Shopify for the sake of balance, because that less-demanding platform makes no claim on customer information. Likewise, game sellers may see the necessity of using both Amazon and the gaming platform Roblox.

For partners, too, the key is customer engagement. How important is the partner to the orchestrator, and to the customer? Insights in this area could give partners more influence on the governance framework of the ecosystem—either by aligning themselves with other players or by pushing for regulatory changes to protect them from the orchestrator’s whims. Indeed, regulation is becoming a key driver of ecosystem dynamics as regulators look at how orchestrators preference their own products or make unilateral changes to how value is shared. These practices are increasingly becoming the focus of regulatory pushback in the EU, the US, and China.

Clearly, the more visible a firm can be to the end customer, the less replaceable it becomes—and the stronger its chances of securing its fair share of the value created. This is what Intel did by branding a previously obscure product—the central processing unit—and making it visible to the PC consumer through “Intel Inside” labeling. (This is also a good example of the double value proposition for partners.) As a result, Intel became indispensable, co-specializing with Microsoft on operating systems and chip design. Nvidia, a much smaller semiconductor company, decided to connect to game developers to develop specialist graphics processors, creating something valuable for game developers and gamers alike. These partnership choices were strategic in that they played to the firms’ strengths: Intel and Nvidia had capabilities that Microsoft and game developers needed. In Intel’s case, once critical mass was achieved in standardizing operating systems, the company could become a partner in multiple ecosystems, as it still is today.

Bringing it all together

A successful ecosystem delivers for everyone involved—orchestrator, complementors, and partners—but it will only succeed if all participants play the right role. Consider, for instance, the choices made by DBS, the Singapore-based banking stalwart, which is an orchestrator of two different multi-actor ecosystems. To move beyond banking and into providing services that engage retail and business customers, DBS has created POSB Smart Buddy, a system for schoolchildren that allows their parents to wire lunch money to a wearable device or app and control their children’s spending. The ecosystem involves technology providers, school canteens and their point-of-sale capabilities, and technological infrastructure, as well as the UI and UX designs that seamlessly connect all these different elements. Similarly, DBS is also building a platform for its B2B users that facilitates their connection to financial services—a different multi-actor ecosystem, with a distinct set of clients and partners. Here, it simply provides the technology and takes a much more hands-off role as the orchestrator.

KPN, the Dutch telecommunications giant, wanted to expand its value proposition to customers across Europe through an ecosystem. It decided to partner with Tencent, one of China’s key ecosystem players, to offer WeChat Go in Europe. In so doing, it created partnership opportunities for other European businesses looking to attract Chinese customers. KPN provides a European SIM card, which enables Chinese visitors to Europe to use limitless data within the WeChat app. This app also provides a gateway to discounts and deals that have been struck with businesses in key European cities such as Amsterdam and Barcelona—creating an add-on ecosystem for European players. KPN not only provides the telecom bandwidth but also helps structure the relationships with local businesses—the complementors in this ecosystem—thus managing valuable webs of relationships on behalf of the orchestrator.

The goal of building an ecosystem strategy and a portfolio approach is to create more value for the business and customers. As the rapid evolution of digital technology, deregulation, and sector convergence plays out, there will be many opportunities in both B2B and B2C. But in this brave new world of possibility, it’s imperative that firms make the right decisions about the roles they want to play. Having a strategic framework for deciding why, when, and how to engage and a guide for the development of an ecosystem portfolio will help companies avoid costly mistakes.

Author profile:

- Michael G. Jacobides is the Sir Donald Gordon Chair of Entrepreneurship & Innovation and a professor of strategy at London Business School. He has written extensively on digital ecosystems and consults on their design and construction as part of the advisory firm Evolution Ltd.