In the shift to hybrid work, don’t overlook your in-person workforce

Many knowledge workers have more flexibility in their jobs than ever before. But in-person workers are feeling overlooked and underappreciated, and many are at risk of leaving.

This is the first of a series of articles looking at sentiments among key segments of the workforce, based on PwC’s Global Workforce Hopes and Fears Survey 2022. Future articles will look at the perspectives of younger workers and women.

Business leaders are highly focused on the shift to hybrid and remote work right now, but they may be overlooking the in-person workforce—factory workers, nurses, delivery people, retail staff, and others whose jobs cannot be done remotely. According to PwC’s recent Global Workforce Hopes and Fears Survey 2022, these workers are significantly less engaged and less satisfied than people who can work from home, and more than one-third of them may soon look for another job.

The survey, one of the largest of its kind ever undertaken, was conducted in the spring of 2022 and drew responses from more than 52,000 workers in 44 countries. Of the total base of respondents, more than 23,000 (or roughly 45%) do not have the option of working remotely—not because of company policies but because of the nature of their jobs.

Labor is an important priority in all market conditions, but it’s an essential one in the highly complex current environment. The challenges of the past few years have caused many workers to change jobs, change careers, or exit the workforce entirely. Labor constraints are having a dramatic impact on industries ranging from healthcare to airlines and hospitality. Moreover, as companies seek to transform and grow, they need to bring their people along—particularly those who have the institutional knowledge to help rethink processes and boost automation efforts. Given these circumstances, the vast in-person workforce is a key resource. If the people who show up to work each day at the office, the store, or the factory are not happy, companies are at real risk of losing them just when they need them most.

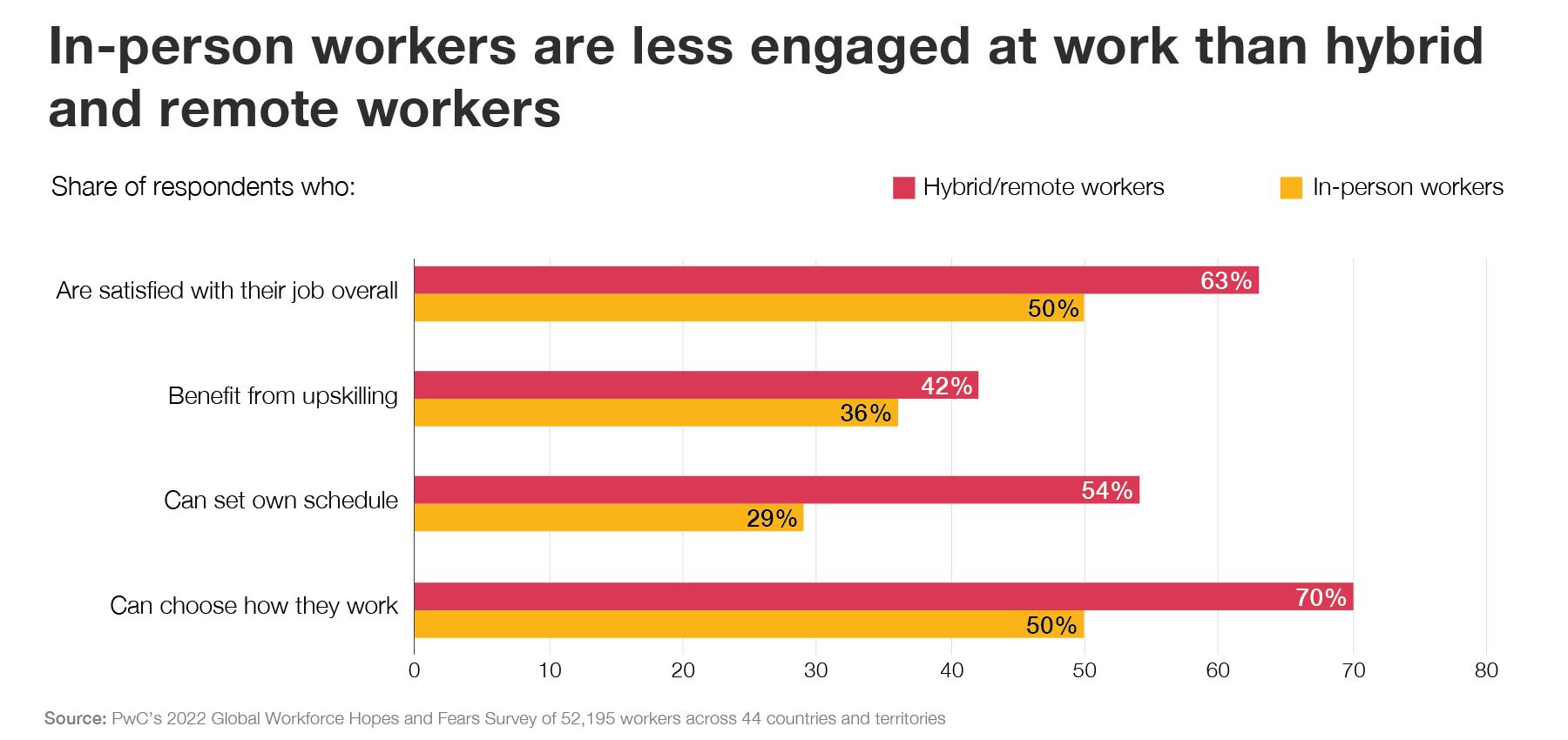

A central finding from the research is that this cohort is less engaged at work than hybrid or fully remote workers, across a range of metrics. Some findings appear to reflect the underlying characteristics of the jobs themselves. For example, in-person workers are less able to set their own schedules or choose how they do their jobs. But other findings highlight deficits that should transcend job descriptions.

In-person workers are significantly less engaged and less satisfied than people who can work from home, and more than one-third of them may soon look for another job.

As the chart below shows, compared to people who work hybrid or fully remote, in-person workers are less likely to be satisfied with their job; less likely to benefit from upskilling initiatives offered by their employer; and less likely to feel that their work has a significant impact on their team’s performance, that they’re fairly compensated, that management considers their viewpoint when making decisions, that they can exceed what’s expected of them, and that they can be creative or innovative in their job.

It is no surprise, then, that more than a third of these workers are extremely, very, or moderately likely to switch to a new employer in the next 12 months.

The findings should raise concerns among business leaders, for several reasons. First, replacing talent is expensive and disruptive. Companies that become more proactive and systematic about retaining in-person workers can boost employee engagement and morale, leading to enhanced productivity, greater retained expertise, and less time and money wasted on replacing talent.

Moreover, there is a broader social element to retaining in-person workers. Many of these people perform critical services that allow society to continue functioning—and enable the rest of the workforce to operate from home. As companies set more ambitious environmental, social, and governance (ESG) goals—particularly the social aspect—they risk a reputational black eye if they take their own workers for granted.

Gauging empowerment among in-person workers

To learn if people around the world felt empowered—or disempowered—at work, we looked at four well-understood dimensions of empowerment drawn from academic research: autonomy; performance/job impact; meaning and belonging; and confidence/competence. By surveying workers on these dimensions (through a total of 12 questions) and then calculating the degree to which the dimensions were both important to people and present in their work lives, we constructed a simple empowerment index, which we then used to evaluate different segments of the workforce.

In line with our other findings about the in-person workforce, the index shows a significant gap in empowerment between those who have the option of working remotely and those who don’t. Index scores declined as time spent in the physical workplace rose, with fully remote workers scoring highest and fully in-person workers scoring lowest. The clear implication? Across multiple dimensions, the in-person workforce feels disempowered compared to their colleagues.

As companies think through their workforce strategies, taking a few critical steps can help. First, make sure that the in-person cohort receives the same amount of consideration as remote and hybrid workers. New ways of working clearly pose challenges in terms of productivity, but there is a real risk in senior leaders focusing most of their time and attention on remote-work issues.

Second, measure employee sentiment, over time, to understand which factors are successful in boosting engagement and morale among the in-person workforce, and where the organization can improve.

Third, look for ways to increase the autonomy of in-person workers. Encourage them to make suggestions about how their work can be done better, and empower them to act on those suggestions. Create some degree of flexibility in terms of scheduling. For example, enable workers to have more say in setting schedules, and allow workers to trade shifts.

Fourth, invest in upskilling initiatives; they are a key driver of empowerment and engagement. They send an explicit signal to workers that they are worthy of investment, and they help workers feel that they are good at their jobs and in control.

Last, leaders should make sure that in-person workers—and all workers—feel that they are contributing to the company’s broader purpose.

As much of the working world pivoted to hybrid and remote work—a shift that looks increasingly permanent at many organizations—in-person workers have continued to show up each day. But as our research shows, they haven’t shared equally in the benefits of that shift. Companies have a choice. They can do nothing and watch those workers leave. Or they can acknowledge the critical importance of in-person workers and take steps to make their work more engaging, meaningful, and fulfilling—creating stronger organizations overall.

Author profiles:

- Bhushan Sethi is the joint global leader of PwC’s people and organization practice. Based in New York, he is a principal with PwC US and an adjunct professor at New York University’s Leonard N. Stern School of Business.

- Peter Brown is the joint global leader of PwC’s people and organization practice. He has more than 20 years of experience helping large multinational corporations redefine the way work gets done and create innovative talent ecosystems that build enabled and agile workforces. Based in London, he is a partner with PwC UK.