Japan’s female future

Demographic realities and the growing number of women in higher education are changing the male-dominated management structures of Japan Inc.

The Japanese corporation, like Japanese society itself, has long been a rather rigid affair, with conservative HR policies and overwhelmingly male in its leadership and character. This is all poised to change, potentially dramatically, over the next two decades. Japan promises to have a far more female future, one that will challenge corporations to become more flexible, creative, and diverse.

On any measure of gender equality, Japan fares abysmally in comparison with other advanced democratic countries. It ranks 110th in the World Economic Forum’s Gender Gap Index, flanked by Mauritius and Belize. Only about one in 10 leadership positions, in organizations of all kinds, are currently held by women. The only comfort, perhaps, is that its neighbor and corporate rival, South Korea, fares even worse with its ranking, at 115th.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who took office in 2012, has promoted the message of letting “women shine,” and he rightly boasts that Japan’s female labor force participation rate has now risen above that in the United States. However, at just under 70 percent of women ages 15 to 64, that rate nevertheless remains below levels in Europe and Canada (75 to 80 percent), and is far below the participation rate of 85 percent for Japanese males. In any case, a greater quantity of jobs for women has not brought greater quality; more than one-third of women are working part time, and roughly the same proportion report in surveys that they are overqualified for their job. Moreover, in his reshuffled government announced in October 2018, Abe found room for just one female cabinet minister.

Japan promises to have a far more female future, one that will challenge corporations to become more flexible, creative, and diverse.

The present and past look dismal, but that does not mean that Japan cannot and will not change. In fact, the country looks destined to do so, for reasons of both supply and demand. The supply of well-educated, professional women surged in the 1990s and 2000s, having lagged badly in earlier decades. And given that Japan is suffering a labor shortage as the working-age population slowly shrinks, demand for that female talent pool is increasing every year. There are no longer sufficient males to take all the good jobs.

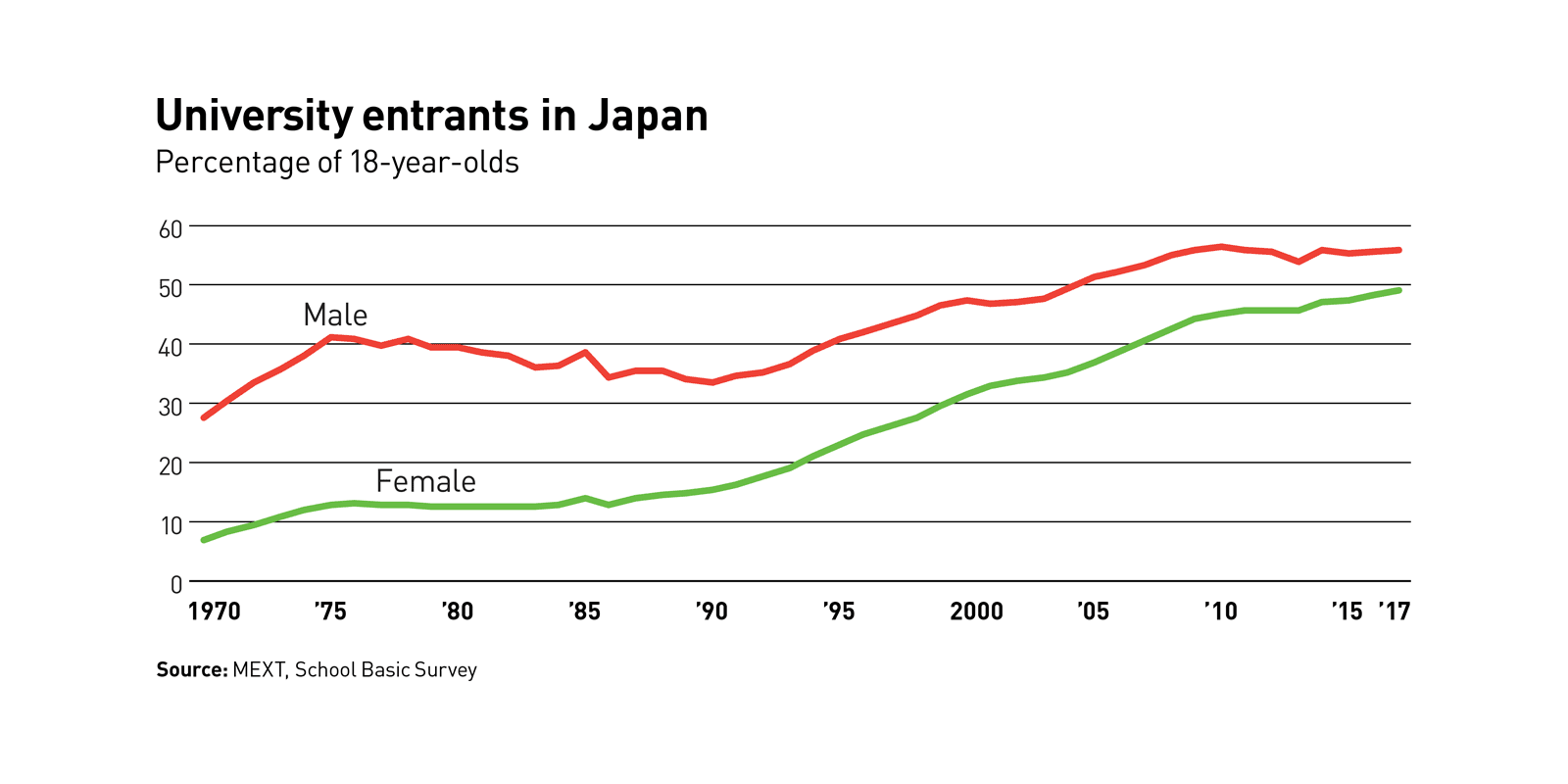

Japan is a very age-conscious and hierarchical society, so the paltry share of women in leadership roles today reflects the huge gender gap in access to tertiary education and corporate recruitment that prevailed when those who are now in their early 50s were graduating from high school, back in the 1980s. At that time, as seen below in “University entrants in Japan,” only around 10 to 12 percent of 18-year-old girls went on to four-year university courses, compared with 35 to 40 percent of boys. Most girls had to make do with two-year “junior colleges,” which condemned them to an inferior status.

Once one factors in a high work dropout rate for those whose children made careers impractical or unacceptable and those who were disillusioned by their poor treatment by employers and male colleagues, the pool of women able to be chosen as top executives, government officials, or politicians — where age-related structures also apply — has been tiny. When Japan’s current ambassador to Ireland, Mari Miyoshi, succeeded in 1980 in being recruited by the foreign ministry for its diplomatic track, she told me, she was the only female among the 28 hires.

A similar story can be told about every current senior female executive — such as Michiko Ogawa, the sole female board director at Panasonic — whose exceptional rise has bucked the educational gender gap. And in politics, where the dominant Liberal Democratic Party operates very much according to age and seniority, the story is much the same. Just one-tenth of Lower House members and one-fifth of Upper House members of Japan’s Parliament are women, and few of that small pool are senior enough to be considered for ministerial positions.

Yet this is all changing. That educational gender gap narrowed, quite spectacularly, in the 1990s and afterward. Families altered their view of what sort of education their daughters should receive, and females demanded more equal treatment. By 2000, the proportion of 18-year-old girls going on to four-year studies had grown to 30 percent; a decade later it reached 45 percent, and it now is nudging 50 percent.

The gender gap in tertiary education is still there, but as the chart shows, it has narrowed to just 5 to 6 percentage points. There are many more professional women working their way through the corporate, institutional, and government career pipeline than in the past. By contrast with Miyoshi’s 1980 experience, in the 2016 intake for diplomatic roles at the Japanese foreign ministry, there were 10 female recruits and 18 males. In this as in other organizations, even if the dropout rate were to remain as high as it has been in the past — and there is good reason to think it will not — the pool of potential female leaders is going to be much larger.

Progress for these new, larger generations of professional women is slow, but it is happening. Mariko Bando, who is now president of Showa Women’s University in Tokyo and previously spent her time as a government official working on and campaigning for gender equality, believes that over the next decade the share of managerial jobs held by women will at least double, and will keep on rising in the 2030s. That rise will be from a low base, but Japan will nevertheless be moving strongly toward a more female future.

The main determinant of how rapidly the country moves toward greater gender equality will be corporate policies rather than government. Public policy can and will have an influence. But companies’ influence will be more decisive.

Traditional human resource policies in large Japanese corporations have relied upon an implicit contract between employer and employee. In return for a pretty much unlimited commitment to work whatever hours are required and an acceptance of whatever postings may be offered, a white-collar employee — a “salaryman” in the slang — has enjoyed full job security. That has left the workplace a predominantly male environment, however, with long working hours and an unwritten but real requirement to regularly socialize with colleagues in the evenings.

For this reason, along with strong social expectations about female roles in the family, the age profile of female workers in Japan used to have a very clear “M” shape, with high participation by those in their 20s, a big drop-off of women in their 30s after marriage and having children, and then a partial return largely to drudge jobs later in life. Now, however, the “M” shape has almost disappeared. But the difficulties of combining career paths with marriage have not.

It is those difficulties that now preoccupy Japanese corporations’ HR departments, just as they preoccupied their U.S. and European equivalents 10 to 20 years ago. The legal maternity leave entitlement in Japan is adequate by international standards. But what has been difficult for women has been to maintain their place on the career ladder and, crucially, on the corporate team, while also bringing up children. Given a Japanese culture in which shared parenting remains rare, they cannot make the same open-ended time commitment as their male colleagues, nor can they accept just any sort of posting that is offered. And they need access to child-care facilities, especially if they do not have grandparents willing to step in.

When there was an ample supply of qualified men, few corporations devoted much time to dealing with these issues. Neither equality nor diversity, in and of themselves, have traditionally been valued in Japanese culture. But now that unemployment is down to just 2.5 percent and the traditional working-age population of 15 to 64 is shrinking year by year, companies face a shortage in terms of both numbers and qualified professionals.

To deal with the labor shortage, firms have lobbied government to bring in more liberal immigration laws — a new act, modeled on 1970s German gastarbeiter policies, was passed in December 2018 and is forecast to allow in 345,000 immigrant workers over the next five years — while also taking on more and more women and retired people on short-term and part-time contracts. To deal with the shortage of qualified professionals, however, companies have had to begin to change their HR policies and their corporate culture.

One important type of shift observed by Machiko Osawa, director of the Research Institute for Women and Careers at Japan Women’s University in Tokyo, has been that of firms choosing to offer managerial experience and development training earlier in women’s careers than had been typical for men, so as to encourage them to remain at the firm and to return to their professional roles after maternity leave. She cites Shiseido, Daiwa Securities, Uniqlo, 7-Eleven, and Calbee as pioneers in such new HR practices.

Other firms are deliberately targeting gender diversity, alongside some diversity of nationality, as a tool of corporate development, something that was truly rare in past decades. A prime example is Sompo Insurance Japan. Its CEO, Kengo Sakurada, has put a strong emphasis on mid-career recruitment — once taboo among big “lifetime” employers — and the promotion of women. His target is to have 30 percent of executive positions held by women over the next decade or so, up from a dismal 2 percent now, by actively recruiting and developing women who are in their 30s and entering their 40s.

Building new child-care facilities has been a key objective of both national and local government policy, and the rate of expansion has been impressive (though it still lags behind demand in many areas). But companies and big institutions such as universities are also stepping in to fill the gap. A high-end provider of nannies, Poppins, also runs more than 200 day-care centers around Japan, many of them on behalf of corporations. The firm was founded 30 years ago by a former TV anchor, Noriko Nakamura, who told me she got bored staying at home with her first child (who is now her successor as CEO). Poppins claims that its fastest-growing business is providing emergency day care on contracts to companies and to other entities, such as the Tokyo Metropolitan Police and Japan Post.

When I spoke in February 2018 at a Tokyo seminar for female subscribers to Japan’s top business daily, the Nikkei, I found a sharp contrast between the views of younger and older audience members. Those in their 40s and beyond stressed the obstacles they had faced and the inflexibility of employers. Younger women, generally in their late 20s and their 30s, took a much more positive stance, feeling that, unlike their elders, they were now being treated more or less equally on the job.

No doubt the reality depends considerably on individual circumstances and different business sectors. It remains true, just as in North America and Western Europe, that Japanese women have a much tougher time combining career and family than men do. But increasingly, the Japanese female career experience is reflecting that in America and Europe, as corporations learn to adapt, forced by necessity.

Unless something unexpected intervenes, the Tokyo Olympics in 2020 will be presided over not just by Abe, the prime minister, but by the female governor of Tokyo, Yuriko Koike, a former party colleague of Abe’s who began her career as a TV journalist. In some ways this female leadership role will be as misleading as Margaret Thatcher’s was as the U.K.’s first female prime minister in 1979: Koike is an exception, not the rule, especially in her generation (she is 66). Nevertheless, she will be a foretaste of what is to come, as younger generations of women rise through the ranks of business and politics during the 2020s and 2030s.

A couple of years ago, a young female employee of advertising giant Dentsu Inc. killed herself seemingly because of pressures from the very male, stressful working culture of long hours. That, in part, set off a government effort to bring in reforms, which came into law in 2018. Though not just directed at women, the reforms could help women’s progress by changing Japan’s macho work culture. It is too soon to judge how much difference the new law will make. What is clear is that Japan’s economic, corporate, and political future is going to be a far more female one than at any previous time in its history. How well the country and its institutions adapt to that future promises to be a key determinant of its success.

Author profile:

- Bill Emmott, a former editor of the Economist, is the author of 13 books, including many about Japan. His next, Japan’s Far More Female Future, will be published in Japanese by Nikkei in May 2019.