The power of feelings at work

By aligning the pursuit of business objectives with the meeting of human needs, companies can tap into powerful emotional forces in their current cultural situations.

Imagine two call centers. In the first, you see smiles and concentrating faces, and overhear heartfelt efforts to help. There is a tangible buzz of hard work but also a feeling of energy and commitment. In the second call center, you see scowls, pained expressions, and eye rolls. Representatives carefully adhere to rote scripts, but their voices lack empathy and warmth. Despite frequent breaks and lags between calls, employees already seem exhausted halfway through the day.

Many would chalk up these differences to culture, the seemingly nebulous and hard-to-control factor that contributes to business success. Our work over the last three decades has centered on culture. We have developed effective tactics to align cultures and strategies and tap into the momentum that a culture can lend to any business effort. What has struck us, again and again, and what we’re sharing now for the first time, is the consistent gateway to this cultural power: It’s all about how people feel. Yes, feelings, those raw emotional responses we sometimes bottle up or even ignore — particularly in a business context — are critically important to business success.

Feelings are messengers of needs. Meeting needs unlocks positive feelings and energy; neglecting needs does the opposite. By integrating business objectives with meeting people’s needs, companies can make sure the strong wind of a positive emotional force is at their back.

The power of feelings

Although momentum is growing in recognition of the importance of emotions in the workplace, the point still begs stressing: Emotions and feelings are powerful. Emotions, defined by neuroscientist Antonio Damasio as the collection of lower-level chemical and neural responses to a stimulus that move an organism toward life-maintaining behavior, help keep us alive by producing quick reactions to threats, rewards, and everything in between (e.g., “There’s a lion! Run!”). Feelings are the mental manifestation of emotions, a way of making sense of the bodily experience. They allow processing and planning in response.

Emotions and feelings bring our needs — human requirements for survival — to our attention and strongly move us toward meeting them. Consider our basic needs for survival: food, water, and oxygen. Our feelings let us know when we fall short on any of these things. We are unquestionably irritable when thirsty or hungry (hence the term hangry). Humans also have core needs that derive from our social existence. We universally crave safety, connection, meaning, autonomy, and play.

Our feelings advocate for our needs. Anger and resentment boil up, asking for connection in a troubled marriage; anxiety and fear call out for safety when an employee is trapped in a role in which mistakes are not tolerated. Conversely, pride energizes teachers’ efforts when they feel in touch with the meaning and larger purpose of their work. When we are in alignment with meeting a need, feelings push us forward: Positive feelings energize and motivate us. When a need is not being met, feelings slam on the brakes: Negative feelings such as anger and frustration block action and contribution.

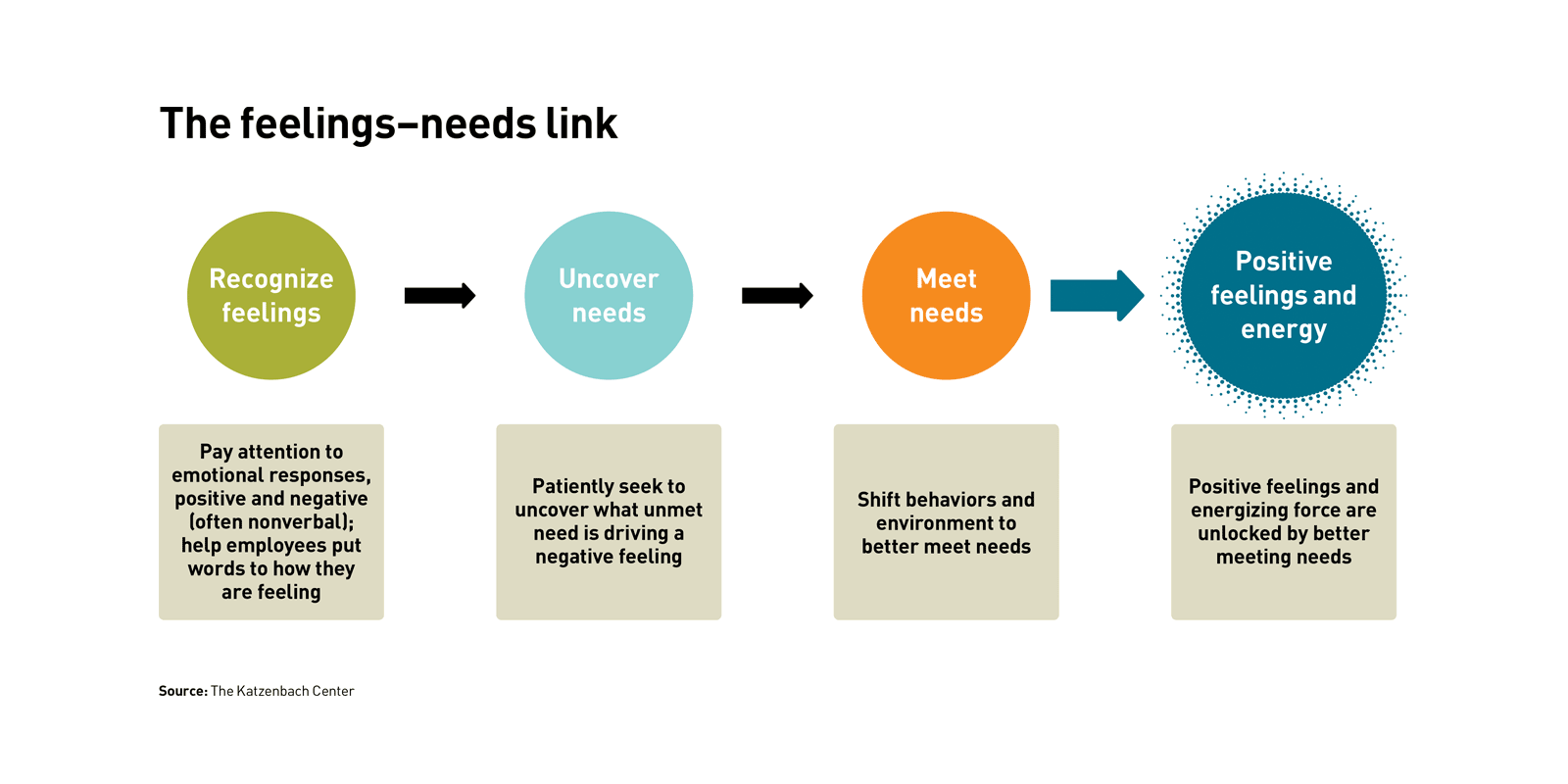

The feelings–needs link

This link between feelings and needs is well established and has been applied across many contexts to improve communication and relationships. But how does it apply to the workplace? The feelings present in a workplace, whether verbalized or not, largely determine employees’ motivation and ability to contribute. How people feel about their work is the most important determinant of success (or lack thereof) for any business. Feelings signal needs, and addressing or ignoring these needs in turn influences the feelings. By recognizing feelings, following them to needs, and acting to address the needs (engaging with what we call the feelings–needs link; see below), organizations can consciously generate positive feelings and energy and create workplaces that are not only more pleasant, but dramatically more productive and successful.

Recognize feelings. Start by trusting the importance of feelings. Rather than looking the other way, or pretending they are not there, begin to recognize and articulate feelings. Managers can open up to their own and their employees’ feelings, both positive and negative, and work to put words to them. Individuals are often not fully aware of feelings even when under their influence. Bringing words to a feeling helps to integrate the brain into the emotion and allow for processing. This can be particularly helpful for negative feelings, because it allows individuals to gain distance from the feeling.

How people feel about their work is the most important determinant of success (or lack thereof) for any business.

Articulating feelings can also bring new understanding to apparent insubordination or poor performance. For example, our firm was once engaged to help an oil refinery stymied by a total lack of response from its employees when it tried to elicit ideas for a cost-reduction effort. To understand what was behind the disengagement, we held focus groups across functions and grades and conducted one-on-one interviews with senior executives. We sought out individuals whom others identified via a questionnaire (e.g., to whom do you go within the organization if you have a problem?) as particularly in touch with employee feelings and asked for their input on what was stopping action. Across the sessions, an articulation of feelings — frustration, fear, and hopelessness — emerged.

Uncover needs. Because feelings are always messengers of needs, the next step is to follow the feeling to the need. Needs are actionable and often multidimensional. Taking action from an understanding of needs sidesteps recrimination and invites compassion. Psychologist Marshall Rosenberg, founder of the Center for Nonviolent Communication, which advocates speaking from needs to navigate conflict, writes, “From the moment people begin talking about what they need, rather than what’s wrong with one another, the possibility of finding ways to meet everybody’s needs is greatly increased.”

At the above-mentioned refinery, we took the feelings as an invitation to dig underneath. A long history of harsh, top-down management and repeated rejections of any contributions had resulted in a widespread feeling that stepping up was risky and jeopardized relationships. Employees longed for safety and a feeling that they mattered. By understanding and then meeting these needs, the refinery could dislodge the negative feelings blocking creativity and collaboration.

Getting to the need requires patience from the listener and introspection on the part of the feeler. It is best achieved by the listener simply asking “What do you need?” and continuing to probe until he or she gets answers that are actual needs as opposed to desired actions in others. At first, the listener might be met with accusations or complaints. He or she should probe further with questions such as “If things were different, what would that give you?” If the listener exhibits patience and discipline, core needs will emerge. It’s a mistake not to consider the most basic needs. For example, lack of sleep can cloud understanding of higher-order issues. There is also a set of common needs one level above the basics that we frequently encounter — almost every organization we have helped has unearthed issues with psychological safety, connection, or meaning.

Understanding what needs are being met in addition to those that are not being met is important; both groups of needs should inform behavior and environment choices for the organization.

Meet needs. By meeting needs, organizations dissipate negative feelings and unlock positive ones that help a business thrive. Needs are best met through action — i.e., behavior — not just messaging. Until we change what people see and feel us doing, we fall short of the motivational opportunities at our fingertips. At the refinery, our focus groups provided a first step in meeting the need for psychological safety by creating an environment in which employees could openly share their feelings. The vulnerability of sharing and having someone listen began to establish connection. Leaders also made a concerted effort to shift their behaviors in response to the identified needs. They changed their responses from “Stop bringing it up” to “Thank you, please keep noticing.” They began circulating and asking employees for ideas. Whether their ideas led to savings or not, employees received literal pats on the back, smiles, and gratitude. Leaders and employees connected over discussing and developing ideas.

The sustained application of these new behaviors helped fill the needs for safety and connection. The stifling frustration, fear, and hopelessness lessened, and employees began to share, and this ultimately resulted in transformative contributions. An operations employee, for example, felt empowered to question the need to run the cooling fans all year round. His insight translated to more than US$400,000 in annual savings. Collectively, the employees identified approximately $4 million of annual savings during the initial engagement, and the ideas and savings kept coming well beyond this period of focused inquiry.

Behavior changes, even those that represent clear benefits for employees, require active reinforcement — including accountability mechanisms and human champions. A management consulting team leader, worried about exhaustion on her teams, began encouraging more rest. But when the sincere urging hardly affected the entrenched behavior, she established “the energy audit.” Every workday she asked members of her team to email or text one item they were taking off their to-do lists for the day. She celebrated these removals and sometimes asked for bigger ones if they seemed too trivial. She applied the same rule to herself. The concrete actions, along with constant reminders from the manager, produced far better results than lip service. The required daily check-ins kept the new behaviors top of mind. And the committed team leader continued to model their use.

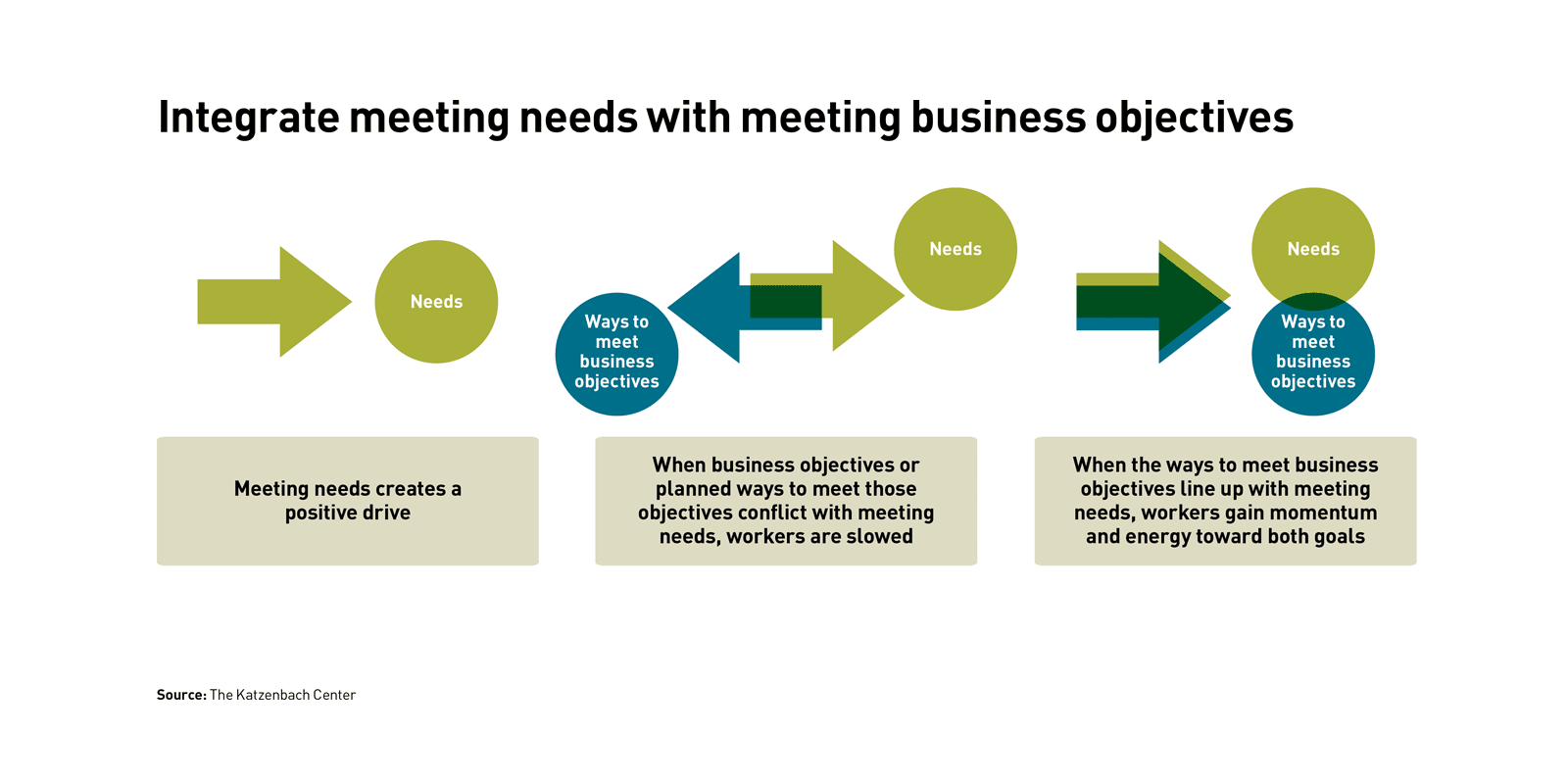

Integrate business objectives

Meeting and engaging with needs produces a happier workforce and often incidentally improves performance. The consulting manager who engaged in energy audits improved her client reviews even as her teams put in less work and less face time. But if companies can line up their own objectives with meeting employee needs, they not only unlock positive feelings broadly but attach the force of this emotional energy to their specific goals (see “Integrate meeting needs with meeting business objectives”).

Companies can think about this integration in three principal areas.

Aligning change efforts with meeting needs. We recently worked with an energy provider seeking to become more nimble. When we first connected, decisions at the company took an average of two months to execute. Each decision required the formal sign-off of each of the 12 members of the full leadership team.

Thinking this sign-off process must have been the root of their slow decision making, they abolished it, reducing the number of needed signatures to only three. But after implementation of the new requirements, decision time went up by an additional month! Why? Given their history of hierarchical control and consensus-based decisions, leaders did not feel safe moving forward without checking in with the full leadership team. So leaders were still painstakingly consulting the whole team for all decisions and were now scheduling formal meetings with every leader not officially listed on the documents. Moreover, senior leaders reinforced the behavior, with encouragement and statements such as “You did the right thing by coming to me,” which responded to employees’ need for connection while encouraging the continued redundancy. Only after we identified these needs for safety and connection, and disconnected meeting those needs from the decision process, did decision time collapse dramatically — from months to days.

Shaping identity and core principles to meet employee needs. The U.S. Marine Corps, through both messaging and countless micro-behaviors, tirelessly emphasizes two simple priorities: (1) achieving the mission (the purpose) and (2) taking care of each other (connection). Almost all training and interaction consist of high-stress challenges that are impossible to accomplish without acting as a team (e.g., intense problem solving, carrying extremely heavy loads for long distances as a group, making all the beds in the barracks in less than five minutes). The intensity and the need to perform as a group quickly and solidly connect participants. The repeated reinforcement allows being a part of the Marines to fill needs for connection and purpose in its members, thus generating intense loyalty and energy toward the organization and all that it seeks to accomplish. It is no surprise Marine platoons have more survivors and bring back more wounded and dead than other armed forces groups under similar battle conditions.

Designing roles that respond to needs. Psychologist Frederick Herzberg told us years ago, “The best way to motivate workers is by focusing on the work itself.” A manager we met in our early work at Bell Canada consistently applied this principle, distributing work in ways that responded to his team members’ needs. For example, he identified in one woman a need for challenge and purpose, which was satisfied by working on problems others could not fix. By shifting her workload to encompass almost exclusively these seemingly intractable puzzles, the manager boosted her motivation and mood and decreased frustration for other team members. Shaping the motivating principles to align with meeting needs can also unlock more positive feelings among employees toward the work they must do.

Tapping into feelings

It is possible to follow and tap into emotional energy wherever you are in the organization and wherever your organization currently is on the emotional intelligence spectrum.

We have found, when trying to embed these new ways of engaging, it is best to have clear goals in mind. We often choose one or two organizational priorities or a key initiative and introduce use of the feelings–needs link in supporting these goals. The clear objective (e.g., lower costs, higher customer satisfaction) makes the work more focused and less intimidating and more relatable and measurable. The objectives also provide a place to start inquiry. We can hold focus groups and conduct interviews on the specific topic. How do people feel regarding activities related to our chosen top objectives/priorities? Where is there resistance? What lies underneath that resistance? In this context, you can also educate people on the feelings–needs link and provide a reminder of when to use it. Work to support the initiative becomes synonymous with applying these concepts, thus helping individuals build a habit of using them. Nothing works quite as well as replacing a “bad” habit with a “good” habit.

Several key actions support the work.

Demonstrate priority. Although middle managers can begin this work without leadership buy-in, leader messaging and modeling dramatically reinforces it. Leaders may not yet be adept in how to engage with their own and others’ feelings. But simply attempting to apply the concepts sends a powerful message. In addition, pointing out and celebrating where others are successfully following the feelings–needs link signals its importance to the organization. Leaders can also demonstrate priority by including updates on “feelings climates” related to top priorities in meetings and reports.

Find your superheroes. Every organization has certain individuals, whom we call “authentic informal leaders,” who are more attuned to connecting on a feelings level and responding to needs. They are comfortable with feelings, adept at uncovering needs, and intuitive about which changes in behavior, either within themselves or organizationally, will begin to meet a need. As employees, they are also familiar with the organization and trusted by their peers. Invariably, we’ve found it immensely useful to seek out and involve these individuals early in the process. Recognize their “feelings work” as high impact, and create more time for it. As you change the nature of these individuals’ work, be sure to maintain or increase their role in key decisions. Create more ways for them to meaningfully interact with one another, and with individuals across the organization (e.g., by involving them in broad corporate initiatives or placing them on interdisciplinary teams), thereby spreading their positive influence.

Build the muscle. Anyone can improve their awareness of feelings and needs. Multiple firms offer training in feelings engagement. For example, Oji Life Lab offers both in-person and technology-based trainings for corporations on recognizing, managing, and understanding emotions in the workplace. Investment in these types of programs not only helps build the skills but also sends a signal of their importance to the organization. Hiring provides another channel for building institutional emotional intelligence. Adding candidates’ ability to manage and engage with feelings as a hiring criterion is a necessary and sometimes overlooked first step.

This understanding of feelings and needs crystalizes and reinforces many of the findings we have stressed for years — the importance of informal leaders, the impact of behaviors, and the force of emotions. The feelings–needs link has been the implicit substance of our work for years. It is the essence of our “critical few” approach. By making it explicit, we hope to make the process more accessible and actionable for all. Feelings are not always the first topic for discussion, especially in the workplace. But when stakeholders understand that such discussion can surface unmet needs, unleash creative thinking on how to meet those needs, and unlock positive energy as they are met, the enterprise proves its worth. By attending to needs, both generally and in the design of roles, corporate priorities, and specific initiatives, organizations can place an immense store of positive energy behind their objectives. It’s a commonsense approach that delivers positive results for both the business and the workers. We encourage you to get started.

Author profiles:

- Jon Katzenbach is an advisor to executives for Strategy&, PwC’s strategy consulting group. He is a managing director with PwC US, based in New York, and founder of the Katzenbach Center, Strategy&’s global institute on organizational culture and leadership. His books on organizational culture, leadership, and teaming include The Wisdom of Teams (with Douglas K. Smith; Harvard Business School Press, 1993) and The Critical Few: Energize Your Company’s Culture by Choosing What Really Matters (with James Thomas and Gretchen Anderson, Berrett-Koehler, 2019).

- Chad Gomes is an independent consultant who has worked with Jon Katzenbach and the Katzenbach Center in various capacities since 2005. He frequently serves as a Katzenbach Center senior advisor on client engagements.

- Carolyn Black is an independent consultant and executive coach based in New York City. She focuses on the development of self-reinforcing positive work relationships and environments. She has worked closely with Jon Katzenbach and the Katzenbach Center since 2016.

- Also contributing to this article were Reid Carpenter, global leader of the Katzenbach Center; PwC US director Carolin Oelschlegel; and PwC director Kristy Hull.