A Challenge for India

N.R. Narayana Murthy, chief mentor and cofounder of Infosys Technologies, sees a bright future for developing countries — if they can use their success to address the problems of poverty.

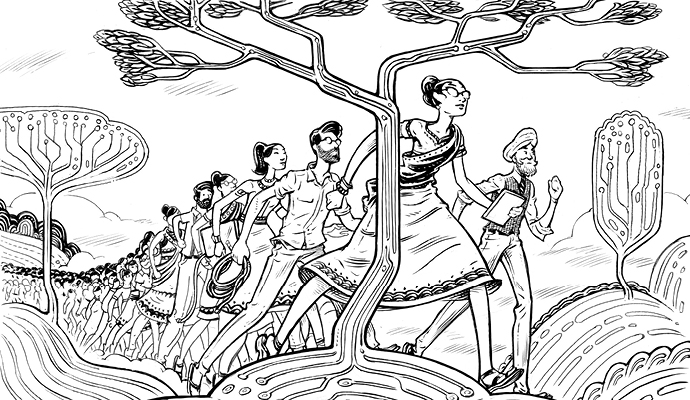

(originally published by Booz & Company)Infosys Technologies, one of India’s oldest and biggest software companies, is a dominant player in the outsourcing industry. And its cofounder N.R. Narayana Murthy has helped drive India’s emergence as a global economic powerhouse. He recognizes the enormous growth that lies ahead for India, China, and other developing nations as they take greater part in the global economy, but also sees challenges. For Murthy, who has long eschewed the trappings of wealth in favor of a more modest life, India’s success — and, implicitly, the continued growth of other developing nations — will not be guaranteed until its benefits reach the country's rich and poor alike.

S+B: In which directions do you see globalization moving?

MURTHY: I define globalization as the paradigm that helps corporations to source capital from where it is cheapest, to source talent from where it is best available, to produce where it is most cost-efficient, and to sell where the markets are, without being constrained by national boundaries. That paradigm will continue to gain momentum as competition from regions that have not always been part of the international marketplace — China, India, Eastern Europe, and Southeast Asia — continues to intensify. Because there’s greater competition, because there’s greater need to become more efficient, to give better value to the customer, there will be greater movement toward offshoring and toward using the entire global talent pool.

China, for example, is working furiously to enhance its contribution to outsourcing in the knowledge area, in software, in business process outsourcing, in financial systems, and so on. And India is also moving up the value chain. We believe that activities such as research, analysis, and preparation of presentation materials can all be done from countries like India.

The huge, educated populations of countries such as China and India are accelerating this process. Higher education levels lead to higher per capita revenue productivity. We’ll see a number of developing countries move along the path toward educating their populations, and that trend will reduce the economic differences between them and the developed nations. There’s a growing recognition that aid from developed nations is not the solution to poverty. The better model is to focus on education, on developing talent, and on building infrastructure, and then to bring the best products and services to the global bazaar.

S+B: Will the U.S. eventually lose its economic leadership to developing countries?

MURTHY: No, I don’t think so. As long as the U.S. welcomes talented individuals from across the globe who can contribute to building the nation’s powers of innovation, it will continue to enjoy a competitive advantage and will never lose its preeminence. India and China are producing higher-value-added products and services. For example, today you see laptops and iPods being made in China. But they’re all still designed in the U.S. Similarly, India is producing more complex software and will one day produce the software that will run the heartbeat systems of an increasing number of global corporations. But even though China and India will keep climbing the value chain and getting better prices for their work, I believe the U.S. will be the leader in innovation.

S+B: Are protectionist U.S. policies hurting its competitiveness?

MURTHY: Globalization is about each country bringing to the global bazaar its best competencies, products, and services. At this point, India has a clear advantage in terms of information technology talent. And I believe the U.S. should make it even easier for American corporations to tap that talent to make themselves more competitive. The concern over job loss is real, but it’s shortsighted.

The fact of the matter is when Toyota, Ford, and General Motors came to India, they squeezed out the inefficient local carmakers and we lost millions of jobs. The same thing happened when Dell came to India and overtook the local computer makers. But we accepted that it is better to suffer the loss of a few million jobs — and pay the cost of retraining all those workers to take on jobs that make India more competitive — than to support inefficient companies and inferior products. Similarly, I think Indian companies will contribute to making corporate customers in the U.S. more efficient by providing them with better products.

S+B: What are India’s main globalization challenges?

MURTHY: Bringing the benefits of globalization to the rural poor is the single greatest challenge to India’s continued success. Although it has helped urban people enormously, globalization has not made any difference to rural people, who constitute 65 percent of the country’s population. The benefits of globalization have not trickled down to them, and that inequity has created tremendous political tension.

People in rural areas believe our politicians are favoring the urban centers by building infrastructure there and enlarging their global economic role. Rural voters have already voted out pro-globalization leaders in two states. How do Indian business leaders convince the rural voters that integrating the country into the global economy is the best way for us to address the problem of poverty throughout rural India?

First, we have to better articulate how globalization is going to help the entire country. Second, we have to focus more on agricultural productivity. Third, we have to build infrastructure in rural areas to support business development and create jobs. If we don’t do these things quickly, I don’t know whether we can continue successfully on this path.

If we ignore these problems, the poor will start to view corporate leaders as villains, and their elected representatives will start working to reduce the power of business. Anti-business policies will slow our growth.

S+B: What specific measures can India and developing countries take to alleviate poverty and address the problems of the poor?

MURTHY: We have to focus on the low-tech manufacturing and services sectors to create job opportunities for the vast majority of Indians who are illiterate or semi-literate. To do this, as I just mentioned, we first have to quickly build infrastructure in rural areas so that businesses can create job opportunities there. Second, we have to move people from agriculture to low-tech so that we can reduce the number of people dependent on agriculture and thus improve productivity. Third, we must target subsidies directly to the poor, eliminating middlemen. The late Milton Friedman’s voucher system would be a good approach, but if such a system is difficult to implement in India, we may want to provide direct cash subsidies to the bank accounts of women in families below a certain annual income who can in turn spend the money on what they need most. To go with this system, we need a new paradigm, in which the private sector can complement the subsidies by providing basic services to the poor, profitably. Finally, we have to focus on improving efficiency and accountability in government services to the poor, including education, health care, nutrition, and shelter.![]()

Sheridan Prasso (sheri@sheridanprasso.com), a contributing editor at Fortune, is the author of The Asian Mystique: Dragon Ladies, Geisha Girls and Our Fantasies of the Exotic Orient (Public Affairs, 2006).