It’s time to stop calling every firm that uses technology a tech company

Defining a company begins by looking at what it produces and sells, not at what enables it to do so.

A version of this article appeared in the Summer 2020 issue of strategy+business.

Online cycling-class provider Peloton isn’t a tech company. Nor are ride-sharing services Uber and Lyft, work-space provider WeWork, online fashion stylist Stitch Fix, meal delivery service Blue Apron, or content creator and curator Netflix, to name just a few that have been given that moniker.

The overuse of tech as the modifier du jour recalls the Internet-bubble age. In the late 1990s, companies that weren’t centered on clicks or whose online-oriented business was founded in vain added .com to their names to get Wall Street cred and attract venture capital. Now, it seems, tech is — or wants to be — a similarly magic word.

The overuse of tech as the modifier du jour recalls the Internet-bubble age.

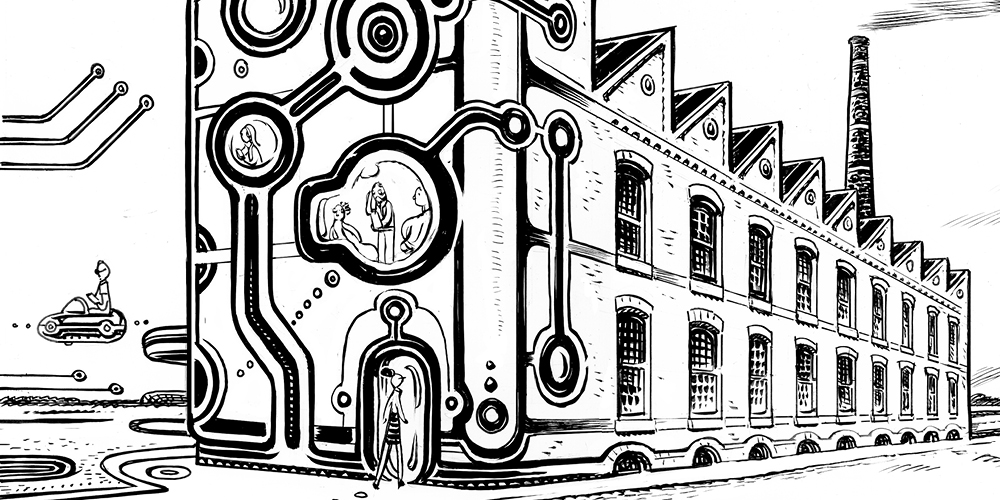

To be sure, digital technology is an enabler, maybe the most powerful one since electric power. Technology’s capabilities have grown to the degree that it has not only become essential to doing business but has transformed entire industries and sectors. For example, with Amazon in the vanguard, technology transformed retail. But Amazon is still a retailer, not a tech company. Peloton, with its 21st-century, Internet-connected bikes, isn’t exactly Schwinn. Nor is it the cycling class at your local gym. Nevertheless, Peloton is a fitness company — a tech-enabled one, but a fitness company all the same.

It’s important to draw a distinction between what a tech company is and isn’t not only because mislabeling could portend another stock market bubble, but because management’s attention, like other resources, is limited. A tech-bedazzled management is liable to spend too much time, money, and energy on the underlying technology, or the touting of it, rather than on what will ultimately determine whether the company can grow, scale, and prosper.

So how do we decide which companies get to be called tech companies and which are using the term as sleight of hand? Defining a company begins first by looking at what it produces and sells. Second, going deeper, it means asking not just what the company sells, but what the customer buys. (Or, in the language of the late Harvard Business School professor Clayton M. Christensen: What job is the customer hiring the product to do?) Finally, defining the company means asking who the competitors are and why customers choose one company over another. The first element is what a company sells; the second is what customers want; the third is what they want from that specific company. The sum of those answers will tell you what that company is and what it should be designed to be.

Ultimately, defining a business must concern the results delivered to consumers, not the journey that products and services take to reach the customer. And too often technology — how the company got to where it is — ends up being a distraction for management, employees, investors, and other stakeholders. Everyone needs to be clear on the focus of the business. Investors and employees in particular need to keep their eye on how value is created by the company. Is technology the source of the value, or merely part of how value is created?

It’s true that there are all kinds of hyphenated and hybrid tech company monikers — fintech, health-tech, martech (marketing technology) — that have carved out processes that were once functions in integrated companies and made them into separate businesses. For example, online bank Simple offers only personal banking services — no mortgages, investment vehicles, or small-business loans such as you’d find at banking behemoths.

And some companies are using tech to change the way a service is delivered: Candid is an online orthodontics company that sells plastic aligners and retainers for people who want to fix their smiles without the frown-inducing fees of traditional orthodontia. At Candid, a patient will never see an orthodontist — though a licensed orthodontist will see 3D scans of a customer’s mouth and devise a start-to-finish treatment plan. And 3D printers will produce the aligners and retainers, which are mailed to the customer’s home, eliminating the need for office visits.

Although Candid relies on technology to create the entire customer experience, it isn’t a tech company. It couldn’t succeed as a business if people didn’t end up with straighter teeth. And its competitors are orthodontists, not, say, data science companies.

Using technology and tech platforms can make growth faster and less capital intensive. And technology may improve customer experience. For Stitch Fix, technology does both. Sophisticated algorithms help advise stylists on what clothes to offer customers, making it cost-effective to provide personalized styling for busy shoppers who can’t afford the personal shopper experience at high-end department stores. But Stitch Fix calls itself an online styling service, not a platform or some other jargony term.

Contrast that with WeWork. The company’s ill-fated prospectus (under the name We Company) used the word technology more than 100 times, according to the Washington Post. Former WeWork chief product officer Shiva Rajaraman told TechCrunch that the company was “moving toward [becoming] a Google Analytics for space.” WeWork aimed to attract gig workers and pitched the vision that it was building community and changing the way people lived, not merely where they worked. Before he was bought out, WeWork founder Adam Neumann made grandiose claims that the company would “elevate the world’s consciousness.” No. WeWork’s business was renting and subletting cubicles and conference rooms to gig workers, startups, and big companies that needed some temporary office space. Little surprise that when WeWork recently appointed a permanent CEO, it went for someone with deep real estate experience: Sandeep Mathrani, former CEO of Brookfield Properties’ retail group.

WeWork’s closest competitor is probably Regus. Unlike WeWork, Regus doesn’t aspire to change people’s lives or save the planet, let alone be a tech company. It provides an upscale and professional temporary working environment. You’re less likely to find the hoodie-wearing crowd at Regus; look instead for khaki-clad men and casually but smartly dressed women. Look again and you’ll see US$3.5 billion in revenue and $485 million in EBITDA for parent company IWG.

Being powered by technology, engaging with customers exclusively online, and avoiding personal contact with humans does not a tech company make. Nor does the label tech company — deserved or otherwise — carry or imbue cachet. Companies should embrace their identities, not try to come up with alternative ones.