When Cookie Monster Goes on a Diet

Consumers’ bonds with brand characters are much like trusted friendships. And when that old pal gets a makeover, certain consumers will be resistant to the change.

Bottom Line: Consumers’ bonds with brand characters are much like trusted friendships. And when that old pal gets a makeover, certain consumers will be resistant to the change.

Smokey Bear, the Geico gecko, Mr. Clean. Not only are these iconic characters instantly identifiable, but they also can feel like much more than marketing gimmicks. Over time, characters such as these begin to feel like trusted friends.

Research continues to show that well-known characters positively boost consumers’ attitudes toward a brand. Such brand characters have also been shown to provide more of a bulwark against bad publicity than, for example, simple non-personified logos. That’s because when people are exposed to brand characters in childhood, or bond with them over time, it’s not unlike forming a friendship: People cultivate deep emotional connections with brand characters and come to feel they know and trust them.

But sometimes marketers tweak these friends in the face of developing trends and cultural norms — consider the changing wardrobe and hairstyle of Columbia Pictures’ “lady with a torch” as attitudes toward beauty and fashion have evolved.

And just as with any other friendship, sometimes someone changing too quickly can leave the other friend (in this case, the consumer) feeling abandoned, wondering where his or her old pal went.

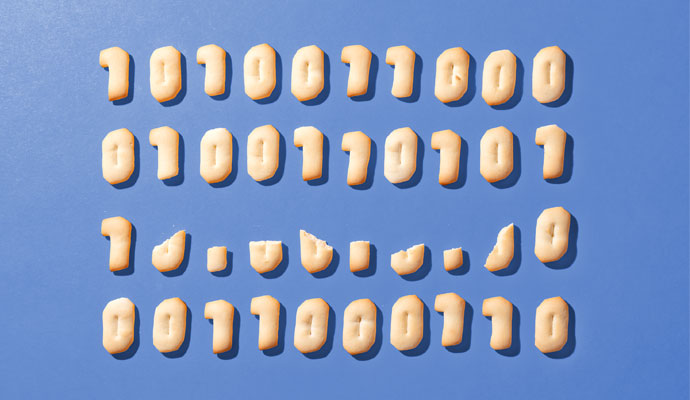

The Public Broadcasting System (PBS) had to grapple with this problem when then first lady Michelle Obama launched a campaign against childhood obesity. Sesame Street’s Cookie Monster, who gobbles up treats with his catchphrase “Me want cookie!,” suddenly didn’t send the right message to kids.

The authors of a new study decided to use PBS’s dilemma to explore how alterations to an iconic character influence consumer opinions and subsequent actions toward the brand. They also explored which types of consumers are most sensitive and resistant to this type of change. Because PBS is a nonprofit, the authors could use the unique measure of donations to see how brand changes affected the consumers’ willingness to financially back a company, moving beyond the opinions they expressed on social media. (However, it’s important to note that Cookie Monster has corporate ties, too — he starred in Apple’s iPhone TV commercial introducing the hands-free Siri service.)

The authors conducted research in several parts to measure the effects of Cookie Monster’s character changes on consumer opinions. Each stage involved different participants, who answered questionnaires about their own personality as well as their responses to a particular version of Cookie Monster.

In the first experiment, participants were shown invitations to donate to PBS featuring one of three images: the “classic” blue Cookie Monster munching a cookie, a blue Cookie Monster eating fruits and vegetables, or a green Cookie Monster eating fruits and vegetables.

Unsurprisingly, the classic look elicited fond, nostalgic memories from respondents: “It does bring [back] family memories, my grandma always had fresh homemade cookies. He [Cookie Monster] eats whatever he wants. Those were safe times.” The second version, however, elicited harsh critiques of Cookie Monster’s newfound dietary responsibility. “Everything I knew about the Cookie Monster is gone,” one 27-year-old participant said. “I feel…tricked.” Many participants didn’t even recognize the third, green-colored version as the Cookie Monster, and thought it was a new character being introduced to Sesame Street.

Beyond the harsh criticism, the authors found that consumers expressed their displeasure by refusing to open their wallets. Respondents who saw the familiar Cookie Monster said that they were much more likely to donate to PBS than were people who expressed confusion with or disapproval of one of the “new” Cookie Monsters.

People cultivate deep emotional connections with brand characters and come to feel they know and trust them.

Next, the authors sought to determine which types of personalities were most attached to iconic brand personalities. In the second experiment, participants viewed either a Cookie Monster eating cookies or one eating fruits and vegetables, and registered their responses. The results revealed that consumers who have a low need to “belong” to groups in society — people who are more solitary, introverted, withdrawn from others, and emotional — felt the most deeply connected to the traditional, familiar brand character. Presumably, these strong bonds with brand characters supplant or augment introverts’ friendships with people.

The type of consumers least likely to donate when confronted with an unfamiliar or changed brand icon were those who tested as anxious, fearful, or emotionally distant in general, the third experiment showed.

Finally, to mimic the emotions people feel in a struggling relationship, the authors primed half of the participants to experience feelings of rejection — they were asked to write a short essay on a time they argued with a close friend or family member. The authors found that people who expressed stronger feelings of rejection reacted more negatively to changes to a brand character, and were less willing to donate. This was especially true for participants who were more socially withdrawn.

So if you’re a brand marketer contemplating making changes to your brand’s icon or image, you may want to proceed cautiously when introducing modifications. Brand characters are especially treasured by socially withdrawn consumers and people who are anxious or fearful. If you do decide to rebrand, your marketing campaigns should perhaps focus on this subset of consumers, seeking to assuage their fear of change with either cheeky or serious acknowledgments of the tweaks, and a reaffirmation that the brand’s essential qualities remain the same.

Source: “Should Cookie Monster Adopt a Healthy Lifestyle or Continue to Indulge? Insights Into Brand Icons,” by Altaf Merchant (University of Washington, Tacoma), Kathryn A. LaTour (Cornell University), John B. Ford (Old Dominion University), and Michael S. LaTour (Ithaca College), Psychology & Marketing, Jan. 2018, vol. 35, no. 1