Why ‟Keeping It Simple” Can Be a Complicated Mistake

When you apply simplistic solutions to complex challenges, you miss out on bigger opportunities.

(originally published by Booz & Company)“Our people are dealing with complex problems. We’d like to bring you in so you can stimulate a thoughtful conversation, and hopefully stir up some big ideas that will take us forward.”

As a self-employed leadership consultant, I used to hear this kind of thing a lot, mostly before the 2008 financial crisis. Colleagues report that they did too. The prevailing sentiment at the time seemed to be that executive seminars and retreats should provide time and space for participants to go deep, reflect, expand their thinking, and cultivate insights that would nurture innovation and help their organizations adapt to a changing world. Results might not be immediate, but that was considered understandable, given that cultural evolution is an organic process.

I rarely hear this kind of sentiment anymore, despite the fact that so many organizations are focused on the mantra of fostering change. In fact, during the initial planning stages of a retreat or conference, I’m often told just the opposite, with some version of the following message:

“One thing you need to know is that our folks are very busy. They don’t have the time or bandwidth to deal with a lot of big-picture concepts or ideas about the future. What they want are a few simple takeaways––three things they can do on Monday morning.”

Leaving aside the question of whether the leaders in question are really looking for three things to add to their already jammed Monday calendars, I find myself increasing skeptical of this approach. It seems to be based on a faulty understanding of what professionals operating in a complex and demanding environment actually require. Harried and rushed, distracted by technology overload, struggling with compliance issues that keep them mired in a welter of detail, and assailed by requests whose claims of urgency have become routine, the executives I meet these days often seem to be in need of refreshment and renewal rather than additional to-do’s.

Instead of three tips on how to manage invasive technologies, leaders need opportunities to articulate a broad vision of what they’re trying to achieve, so they can better distinguish which tasks require diligence and which can be let go. Instead of exhortations about the need to “manage up,” they need to understand how the erosion of barriers that defined industrial-era culture is leaving the employees they manage exposed to uncertainty and fear. Instead of quick fixes to address shifting markets, they need support to recognize how intersecting trends are creating whole new categories of unmet needs.

The pervasive desire to provide easy answers to complex problems is not limited to organizations. For example, the political scientist William Gorton has noted that political speech has become increasingly simplistic, even as citizens have become more accustomed to dealing with complexity in their daily lives. Instead of describing the impact of a policy on, say, a nation’s capacity to meet its debt, politicians opt for reductive stories about how balancing a multitrillion-dollar budget is somehow akin to “regular moms and dads sorting out bills around the kitchen table.”

Gorton asks if this dumbing down in the political arena, this reliance on faux-folksy analogies, might be a core reason why people have grown more skeptical of government in general. Certainly simplistic explanations underestimate the ability of those at whom they are aimed, citizens accustomed to making sophisticated calculations and trade-offs both at work and at home.

I believe the widespread desire to dumb down complex content may have a similar reductive affect on organizations. By focusing potentially profound conversations on three action points or five bullets, those who plan seminars and retreats risk squandering the opportunity for thoughtful engagement and short-circuiting creative solutions that smart people, given the time and permission to think, are likely to come up with on their own.

Being able to shoot the rapids in an era of constant change requires robust thinking skills. People do not develop these skills by responding to prescriptive formulas, however neatly packaged as takeaways. Planting seeds that may germinate in the coming years is also a useful antidote to the sense of unrelenting urgency that pervades organizational life and that can undermine peoples’ ability to make good decisions.

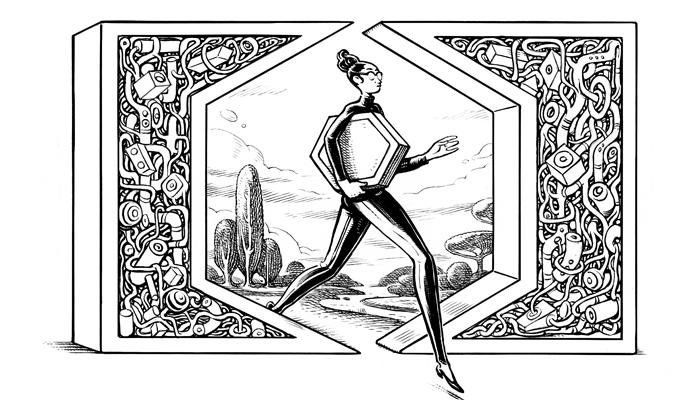

Given companies’ oft-stated desire to help people “think outside the box,” I believe consultants and other service providers do a disservice when we go along with requests to deliver overly simplified solutions to problems that will just grow more complex. Instead, we should push those who engage us to think more profoundly about what thriving in a highly demanding global environment requires. Only by doing so can we support leaders in delivering programs that extend their employees’ capacity to respond to the complexities of today’s economic and technological frontier.