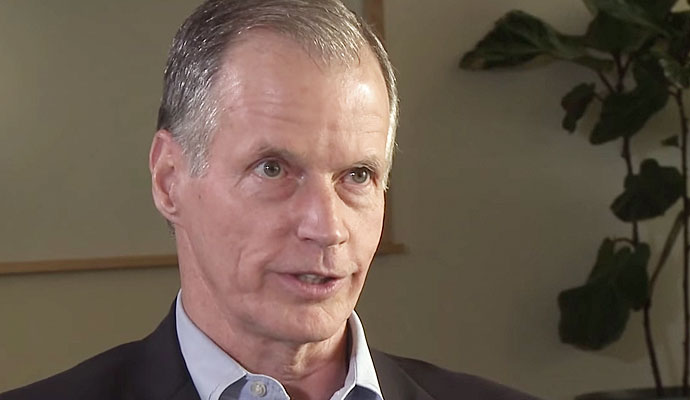

Thomas Malone on Building Smarter Teams

The head of MIT’s Center for Collective Intelligence explains how the social intelligence factor is critical for business success.

What if you could measure the intelligence of a group? What if you could predict which committees, assigned to design a horse, would end up with a camel, versus which would develop a thoroughbred—or a racecar? The MIT Sloan School of Management’s Center for Collective Intelligence (CCI) was set up to accomplish just that sort of evaluation. Under the leadership of its founding director, Thomas W. Malone, the center’s ambition is to put forth a new theory of group performance, bringing together insights from social psychology, computer science, group dynamics, social media, crowdsourcing, and the center’s own experiments in group behavior. The results could help business teams produce more thoroughbreds and fewer camels.

Malone is the Patrick J. McGovern Professor of Management at the MIT Sloan School and a key figure in organizational learning and design studies. Formerly a research scientist at Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), he holds 11 patents, largely in user interface design and the representation of complex processes in software. Like other technologists (one thinks of the late computer interface pioneer Douglas Engelbart), Malone grew interested in the ways that organizational design and computer systems design could augment each other. His book The Future of Work: How the New Order of Business Will Shape Your Organization, Your Management Style, and Your Life (Harvard Business School Press, 2004) proposed that in an increasingly networked world, strict hierarchies would be less viable. The book also foreshadowed the decentralized “bottom-up” management model that has influenced companies like Zappos.

Malone set up CCI in 2006, drawing together a group of management scholars, neuroscientists, and computer scientists (some of whom, including Alex “Sandy” Pentland, Erik Brynjolfsson, and Pattie Maes, have been featured in our pages). Tim Berners-Lee, Jimmy Wales, and Alpheus Bingham—the progenitors of the World Wide Web, Wikipedia, and the crowdsourcing platform InnoCentive, respectively—make up the center’s advisory board.

CCI’s most provocative finding so far is that, by and large, the higher the proportion of women on a team, the more likely it is to exhibit collective intelligence (and thus achieve its goals). This research was originally published in Science (“Evidence for a Collective Intelligence Factor in the Performance of Human Groups,” by Malone and Carnegie Mellon assistant professor Anita Williams Woolley et al., Oct. 2010) and highlighted in April 2013 in a Harvard Business Review interview with Malone and Woolley. The critical factor appears to be social perception. Women are, on average, more perceptive than men about their colleagues. Social perceptiveness is a kind of social intelligence; it’s the ability to discern what someone is thinking, either by looking at their facial expression or through some other means of human observation. When it comes to the effectiveness of groups, we are what we see in each other. And if this kind of acumen can be learned, Malone’s research suggests that the performance of teams (and companies) can be dramatically improved.

In December 2013, Malone met with strategy+business at MIT’s Sloan School in Cambridge, Mass. He talked about the origins of his research, the comprehensive study he conducted with about 150 groups, and the implications for individuals, teams, and large-scale enterprises.

S+B: How did your work on measuring collective intelligence get its start?

MALONE: As codirector of the MIT project “Inventing the Organizations of the 21st Century,” I did a lot of thinking about how new technologies would change the ways work is organized. In The Future of Work, I suggested that cheap communications would lead to much more human freedom and decentralized decision making in business. After that, I considered following up with another book about how to implement these ideas, and what companies were actually making them work. But the more I thought about it, the more I became convinced that I should look instead at what was coming next: the evolution of management beyond decentralization.

Around that time, I had dinner with the venture capitalist and writer Esther Dyson and the mathematician and science fiction writer Vernor Vinge. Vernor was working on his book Rainbows End, which describes what he calls “superhuman intelligence” that combines the intelligence of people and computers. Of course, Douglas Engelbart and others had talked about possibilities like this for a long time, and it was certainly something I had thought about, too. By the end of that conversation, I was convinced that I should work on this concept next. It didn’t so much feel like a new idea or an inspiration; I was finally taking a path that, at some level, I had known for a long time was the right path to take.

I began to imagine what it would be like to have very intelligent organizations. From there came the question, which would ultimately be the core research question of the Center for Collective Intelligence: How can people and computers be connected so that—collectively—they act more intelligently than any person, group, or computer has ever done before? When you take that question seriously, it leads to a view of organizational effectiveness that is very different from the prevailing wisdom of the past.

S+B: Why are computers part of the definition of collective intelligence?

MALONE: Actually, they’re not part of the definition. I define collective intelligence as groups of individuals acting together in ways that seem intelligent. In other words, intelligence is not just something that happens inside individual brains. It also arises in groups of individuals. Those groups don’t require computers. In fact, by this broad definition, collective intelligence has existed for thousands of years. For instance, armies, companies, countries, and families are all examples of groups of people who work together in ways that—at least sometimes—seem intelligent.

But the most rapidly evolving kinds of collective intelligence today are those enabled by the Internet. Think of Google. Millions of people around the world create Web pages, linked to one another. Then all that knowledge is harvested by the Google algorithms, so that when you type a question in the Google search bar, the answers you get often seem amazingly intelligent. Or look at Wikipedia, where people all over the world have collectively created a very large and extremely high-quality intellectual product, with almost no centralized control. They do it in most cases without even being paid. I think these early examples of Internet-enabled collective intelligence are not the end of the story, but just the beginning.

To anticipate what’s going to happen in the future, and to take advantage of those possibilities, we need to understand collective intelligence at a much deeper level than people do so far.

Tests of Versatility

S+B: You define collective intelligence as groups “seeming intelligent.” But how do you know intelligence when you see it?

MALONE: Intelligence is difficult to define objectively, even though many people have tried. There still isn’t a single definition that most experts in the field would agree to. The way you just put it—“How do you know it when you see it?”—is actually a useful definition of intelligence. We can’t define it precisely, but we often know it when we see it.

This subjectivity is also unavoidable, in part, because intelligence is linked to the goals of the person or group whose intelligence you’re trying to assess. And as an observer, you can’t always be sure what the subject’s goals are. For instance, if I give you an IQ test scored on a machine-readable multiple-choice form, and you color in the dots so that they make a nice artistic pattern on the answer sheet, you’ll probably get a low intelligence score. But that’s because you weren’t trying to achieve the goal I thought you were. To evaluate your intelligence, I have to make assumptions about what your goals are, and that, of necessity, involves some subjectivity.

S+B: So my assessment of someone else’s intelligence depends on how well they achieve the goals I think they’re trying to achieve?

MALONE: That’s right. There are, of course, other ways to define intelligence. One way that we found particularly useful for looking at the intelligence of groups is the psychometric definition, used by psychol-ogists who measure people’s capabilities. Their definition of being intelligent, at the individual level, is the ability to be good at many things, not just one thing.

For example, many people believe that math and verbal skills are negatively correlated—that people who are good at math are worse than average at verbal tasks and vice versa. But in fact, when you test people on a group of mental tasks and apply a statistical technique called factor analysis, you find that people who are good at one mental task are, on average, good at lots of other mental tasks as well. In fact, it’s that generalized ability at many kinds of tasks that intelligence tests, at the individual level, are designed to measure.

S+B: They’re measuring the versatility of your thinking.

MALONE: Yes. People who are the most intelligent, as measured by intelligence tests, are not necessarily the top performers at any single mental task, but they’re good at learning new tasks and adapting quickly to lots of different tasks. This general ability is called the g factor, or general factor, and it is a measure of general cognitive ability that’s associated with things like logical reasoning, verbal and math skills, and learning. It was first recognized by the 20th-century British psychometric pioneer Charles Spearman, who developed statistical factor analysis as part of his intelligence research.

The g factor has often been criticized as incomplete. For example, as Harvard developmental psychologist Howard Gardner has pointed out, there are other important kinds of abilities that don’t get measured by IQ tests. But basic cognitive ability is important, because it is consistently correlated with success in many endeavors. With an intelligence test, you can measure in less than an hour something that helps you predict many things that are important to a person’s life—their grades in school, their performance in many occupations, and even their life expectancy—that would otherwise take months or years to observe.

Measuring Group Intelligence

S+B: How did you make the leap from individual to collective intelligence in your own research?

MALONE: We started with our basic definition: an intelligent group of individuals is one that acts together in ways that seem intelligent to an observer. As with individual intelligence, the observer has to pick some set of goals with respect to which to evaluate the group’s intelligence. But notice that in this case, the goals the observer uses may not be the same as those of any individuals in the group. For instance, you might evaluate the “intelligence” of a group of pedestrians on a busy New York City sidewalk on the basis of how evenly they distribute themselves over the sidewalk, even though each individual is just trying to get to a destination without colliding with someone else.

Or if you were an economist, you might evaluate the “intelligence” of the buyers and sellers in a region on the basis of how efficiently they allocated the society’s resources, even though most of the individuals in that economy were just trying to maximize their own welfare.

As an observer of collective intelligence, you also need to select the group of individuals that you want to analyze. For instance, you might evaluate the collective intelligence of a small work team, the staff of a department, a whole company, or the American public. Sometimes, you might even want to evaluate the “collective intelligence” of a single person by analyzing how the different neurons in that person’s brain act collectively to produce the person’s intelligent behavior.

Whatever the size of group we analyze, we always need to be able to identify a set of separate individuals acting together, with some interdependence among them.

S+B: How do you measure and compare the collective intelligence of that group to others?

MALONE: Well, we started with the psychometric definition of intelligence—essentially the versatility of thinking. Then we employed the same statistical techniques that are used to measure intelligence at the individual level, but we used these techniques to measure the intelligence of groups. What we really wanted to know was whether there is an equivalent of the g factor for groups. As far as we could tell, no one had ever asked this question before.

So to answer the question ourselves, we brought about 700 people into our laboratories, in groups that ranged from two to five people each. We gave each group a set of tasks to perform together, ranging from brainstorming uses for a brick, to solving IQ test problems as a group, to planning a shopping trip with a number of constraints, to typing long text passages into Google Docs. Each group spent about three hours working together on these tasks.

When we analyzed the results, we found that the answer to the original question was yes. There is a single statistical factor for any group—just as there is for an individual—that predicts how well the group will perform on a wide range of different tasks. This factor accounts for about 30 to 50 percent of the variance in the group’s performance on different tasks, just as the g factor did for individual intelligence. We sometimes call it the c factor, in homage to Spearman’s g factor.

S+B: What does that c factor represent?

MALONE: It’s a statistical indicator in the same way that your score on an IQ test is a statistical indicator. Like an IQ score, it’s predictive of a group’s performance on many other tasks not included in the test itself.

Now that we had a measure of collective intelligence, we also wanted to know what other factors might predict this collective intelligence. And we found four factors that were correlated—four things that might account for the degree of collective intelligence in a team.

The first was the most obvious: the intelligence of the individual team members. We had expected that the group intelligence would correlate with the average or max-imum intelligence of individual group members. But we were surprised to find that the correlation was not very strong. In other words, just having a bunch of smart people in a group doesn’t necessarily make a smart group.

S+B: Are you more likely to have mediocre people become a smart group, or are you more likely to have smart people become a mediocre group?

MALONE: Statistically, either could happen. Of course, we all know from our own experience that you can have very ineffective groups made up of very smart people. Now we have a precise, scientific demonstration of that.

Many other factors that we thought would be significant predictors weren’t. These included things like psychological safety and group cohesiveness. But we did find three additional factors that were significantly correlated with the group’s collective intelligence. The first was the average social perceptiveness of the group members, the second had to do with the equality of contribution, and the third was the ratio of men to women in the group.

The Mind in the Eyes

S+B: What do you mean by social perceptiveness?

MALONE: This is the ability to correctly read the emotions of other people. We measured it using a test developed by the British autism researcher Simon Baron-Cohen. The test is called “Reading the Mind in the Eyes.” You show people pictures of other people’s eyes, and ask them to guess what emotion the person in the picture is feeling. There is a correct answer, and the test significantly distinguishes autistic from non-autistic people. Even among non-autistic people, there’s a significant enough range that it turns out to be useful for a lot of purposes, including this study. We found that a group is more collectively intelligent if the people in it are, on average, more socially perceptive—that is, if they are good at reading emotions from other people’s eyes.

One fascinating aspect of this came up when we did the same experiments with two types of groups. The face-to-face groups were sitting around a conference table, answering the questions on a computer but talking directly to one another. The online-only groups could communicate only through the computer, using text chat. They couldn’t see one another’s eyes at all.

But we found that the same measure of social perceptiveness, the “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” test, was equally predictive of most groups’ collective intelligence. We believe this means that the autism test is actually measuring a broad range of interpersonal skills. Psychologists call these broader skills theory of mind. The term refers to the ability, which is more developed in some people than others, to create a mental theory about what’s inside other people’s brains.

S+B: And if the members of a certain group have a high level of this ability, that group is more likely to be more collectively intelligent?

MALONE: Yes, but that’s only one factor. The second factor was the equality of contribution: the degree to which the group members participated evenly. When one or two people dominated the conversation, the group on average was less intelligent. Here again was a precise confirmation of what many people have perceived in their own team meetings.

The third factor we found that correlated with the group’s collective intelligence was the proportion of women in the group. If there were more women in the group, the group performed better. In general, the higher the ratio of women to men, the better the performance.

In our results, this third factor was largely explained, at least statistically, by the first result. It was known, before our work, that women on average score higher than men on the test of social perceptiveness. So one interpretation of our results is that what you really need for a group to be intelligent is to have lots of people in the group who are high on this measure of social perceptiveness, regardless of whether the people are men or women.

Notice that this is not a standard diversity result. A standard diversity result would have been that the best-performing groups would have about the same number of men and women. We haven’t yet done the research we need to do to explore this finding with more precision. But in our results so far, the groups with half men and half women had some of the lowest scores. And it appears as if the highest scores go to groups composed mostly of women, with just a few men.

Making Teams More Effective

S+B: Do you have a sense of why those three factors are so critical?

MALONE: Although all three factors have roughly equal correlations with collective intelligence, when put into a regression at the same time, the only one that is statistically significant is the first one, social perceptiveness. So, and this is somewhat speculative, one might conclude that the most important factor in collective intelligence is having groups where people are good at perceiving one another’s emotions accurately, or, more generally, where they have high social intelligence.

S+B: Is this a learnable or cultivatable skill?

MALONE: Excellent question, and we don’t know for sure. This quality in people appears to have some genetic component. It may also be influenced by hormones; it’s been negatively correlated with high levels of testosterone. Those are reasons to believe it’s not very changeable.

But there are other reasons to believe it might be possible to affect it. In a study published recently in Science [“Reading Literary Fiction Improves Theory of Mind,” by David Comer Kidd and Emanuele Castano, Oct. 2013], two psychology researchers found that people who read literary fiction for a few minutes before taking the “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” test got a better score than those who did not.

Having good theory of mind skills is not necessarily the same as having empathy. Of course, they’re related. You couldn’t be empathetic without some theory of mind skill, because you wouldn’t even be aware of other people’s feelings. But you could accurately perceive what other people were feeling and thinking, while not caring about them. If you didn’t have any actual sympathy for them, you could use that accurate perception to manipulate or take advantage of them.

S+B: So if you were leading an enterprise and you wanted to have more intelligent, productive, effective teams…

MALONE: One thing you could try is to increase your company’s overall level of social perceptiveness or social intelligence. You might cultivate this by developing that quality in your existing staff. Or, if it turned out to be hard to teach, you might recruit individuals who had it. Or you could create situations that would bring it out.

Other elements of organizational design—how you group and link tasks, and how you motivate people—also clearly have an effect on how intelligent the organization is. For instance, there are now ways of designing nonhierarchical organizations, like crowd-based organizations, that have the potential to be even more intelligent than the best-designed hierarchies.

S+B: How does this fit with the rest of the work you’re doing on collective intelligence?

MALONE: We basically have three types of activity. The first is the scientific studies I’ve just described. Second, we observe the new organizational design patterns that arise, especially in the business world. We call this work “mapping the genomes of collective intelligence.” We looked at more than 200 examples of what we thought were interesting cases of collective intelligence, including Google, Wikipedia, the Linux community, Threadless, and InnoCentive. We started by trying to classify them into discrete categories, as if we were biologists trying to classify new life forms into different species. But the same cases often seemed to belong in more than one category. For example, Wikipedia was both consensus and collaboration.

One breakthrough for us was realizing that the more appropriate biology analogy was classifying genes, not species. We call these elements design patterns, which is a phrase used by the architect and writer Christopher Alexander and his coauthors in their book A Pattern Language [Oxford University Press, 1977]. Not all the ways of assembling them make sense or work well, but you can use them in thinking about how to develop an organizational structure that helps you achieve your goals.

Third, we’re creating new examples of collective intelligence. The biggest project in that area is called the Climate CoLab, where we’re harnessing the collective intelligence of thousands of people all over the world, to come up with new ideas for solving the problems of climate change. We’re essentially crowdsourcing that problem.

With all three of these activities, we’re looking to create smarter organizations. We hope eventually to develop a test we can give to real-world groups, and use it to predict, for example, how well a sales team might perform over the coming year, how well a design group could develop a new product, or how productive a top management group or board of directors would be in devising the next strategy.

S+B: Could you also use the test to increase the collective intelligence of a group?

MALONE: Yes, I think so. Individual intelligence is very difficult to change. You can predict people’s behavior by measuring their intelligence, but it’s usually hard to increase an individual’s intelligence. With groups, however, it seems quite possible that we could change their collective intelligence. At the minimum, you could imagine changing the intelligence of a group by changing some or maybe even all of the people in it—replacing them with people with higher levels of social intelligence, for instance.

You could imagine changing the intelligence of a group by changing the people in it.

There might well be other things you could do too: Change the motivation of the group. Change their incentives. Change their structure, how they’re grouped into subgroups. Change their size. We noticed that in the groups from two to five people that we looked at, larger groups did better. But some data indicates that when groups get larger than about 10 members, they often become less effective.

S+B: How do these organizational interventions relate to the four factors that you found correlated with collective intelligence?

MALONE: We wouldn’t claim that those four are the only four. Those are the only four significant correlations we found in the study we did. But there are clearly other factors that affect a group’s intelligence. For instance, as a group gets larger, the way you organize the group can have a major effect on its collective intelligence.

As a thought experiment, imagine that you have 5,000 people in a football stadium, trying to write an encyclopedia, with no tools other than paper and pencil and the loudspeaker system. If you gave them a few hours to work, they could each scribble some drafts of articles, and they could have people who are editors who approved things. There would be long lines of people waiting to get their articles approved, and in a few hours, they could make some progress.

But now imagine you have the same 5,000 people, and the same amount of time, but every one of the people has access to the Wikipedia software, in a shared database that they compile together. It seems likely that they could accomplish much more good work in the same amount of time.

One interesting possibility is that with the right kinds of digital electronic collaboration tools, we could greatly increase the size up to which a group can continue to increase its intelligence by adding members. Right now, the optimal size is probably somewhere between five and 10, but with the right collaboration tools, you could imagine having a group that kept getting more intelligent, up to 50, 100, or even 500 or 5,000 people. That’s one of the most intriguing long-term research questions we’re starting to work on. Now that we have a way of measuring the intelligence of a group, we can use that to find ways to allow the group to scale to a much larger size without being overcome by the “process losses” that inhibit the performance of large groups today. ![]()

Reprint No. 00257