Sustainable Goes Strategic

Learning from the literature of corporate environmentalism.

|

|

Photograph by Jean Paul Endress

|

Fortunately, after decades of painting environmentalism as fringe thinking (even long after it became accepted by the public as a basic value), the corporate world has come around to seeing green as the future — or at least as a path to profit. Meanwhile, a more robust strain of environmental thinking has come to the fore, shedding the sackcloth-and-ashes, no-growth, less-is-better narrative, and embracing smart growth, new power technologies, and new design strategies. And yet the green practices of most major corporations have remained timid and undemanding, following behind most of the public instead of leading it. These practices are often focused narrowly on energy, leaving aside many environmentally relevant questions.

Every thoughtful executive is asking, “What can our business do about climate change? How can we survive the turmoil?” Or, beyond surviving, “How can we profit from this new imperative for green solutions?” Or, more deeply, “How do we shift our ground so that the survival and growth of this organization line up with the changes needed for the whole global system?” The questions are timely and have no easy answers. Fortunately, however, a number of books and resources have laid the groundwork for resolving them.

Sustainable First Principles

The term corporate sustainability was coined more than two decades ago, in the 1987 Brundtland Commission report (Our Common Future, published by Oxford University Press), as a synonym for “green,” “ecological,” or “environmentally conscious” business practices. Since then, the concept of sustainability has suffered a spectacular amount of mission drift. It has come to encompass “corporate social responsibility” (CSR), a wide range of corporate actions regarding ethics, diversity, healthy communities, and long-term corporate governance. But CSR was a conceptual bolt-on: It was an optional set of practices to put in place after doing what it took to make a profit, build the asset, and keep the shareholders happy.

By contrast, it is becoming clear that corporate sustainability does not primarily mean being a “good corporate citizen”; it means contributing to human survival. More specifically, it means recognizing that environmental pillage and despoliation are no longer sound business practices, and replacing them with another way of doing business. The new credo has been articulated by Interface Inc. Chairman Ray Anderson: “Take nothing, waste nothing, do no harm, and do very, very well by doing good.” (See “Not Just for Profit,” by Marjorie Kelly, s+b, Spring 2009.)

Consider this thought experiment, which appears in Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things, by William McDonough and Michael Braungart: What would it take to run your company the way the Menominee tribe of Michigan runs their forest? In 1870, the Menominee counted 1.3 billion board feet of standing timber on their 235,000 acres of land. Over the last 138 years, they have harvested 2.3 billion board feet, and now they have 1.7 billion board feet. Neat trick. Maybe you’re not in a resource-extraction industry; maybe your capital doesn’t grow on trees. But isn’t there an equivalent potential achievement in your sector?

Operating with a light footprint is likely to become the prevalent approach to sustainability over the next few years. And it begins with some basic principles:

1. Sustainability is based not on helping a corporation look good in public, but on a clear understanding of the effect the company’s processes and products have on the natural environment — and on finding ways the company can make the environment better, not just cutting back harmful emissions.

2. Sustainable policies and practices are simple, comprehensible, and pragmatic enough for employees to execute them and customers to understand them.

3. Sustainability is measurable. Managers can track its processes, implementation, and effects.

4. Sustainable policies are reality-based. They do not deny scientific consensus (about climate change or other environmental impacts) that is based on accumulated evidence, nor do they take every popular green idea at face value.

As you explore your own concept of sustainability, you may be drawn first to the simplest approach: adopting green practices. Bookstore shelves groan with how-to-go-green books, both personal and corporate, from the silly to the daunting. National Geographic has True Green@Work: 100 Ways You Can Make the Environment Your Business (National Geographic, 2008). “Finish Rich” maven David Bach (with Hillary Rosner) weighs in with Go Green, Live Rich: 50 Simple Ways to Save the Earth (and Get Rich Trying) (Broadway Books, 2008). The Better World Handbook: Small Changes That Make a Big Difference, by Ellis Jones, Ross Haenfler, and Brett Johnson (New Society Publishers, 2007), covers such disparate topics as clean energy, the crisis of masculinity, and building better communities.

The most powerful of the how-to lists is Worldchanging: A User’s Guide for the 21st Century, edited by Alex Steffen. A catalog born of the Worldchanging.com Web site launched by futurist writer–editors Alex Steffen and Jamais Cascio, this compendium of strategies, experiments, organizations, resources, and examples has the advantage of having sprung from a continuing conversation in the lively blogs and discussions on the Web. The Worldchanging view of what is “better” is broadly progressive, but the book and Web site combination yields a smorgasbord of options. The word yeasty comes to mind; the word lockstep doesn’t.

The Larger Context

But green practices undertaken without a comprehensive strategy for corporate sustainability will ultimately prove unsatisfying. Moreover, although virtually every serious climate scientist agrees that the climate is changing, and that much of this change is anthropogenic (caused by human activity and in this case specifically by greenhouse gases), the delays built into the climate system suggest that humanity can’t solve this problem merely by cutting carbon emissions, especially given the short time available to avoid disaster.

An effective strategy means reducing any activity that spurs further climate change while simultaneously preparing for life in a changed climate. If books and resources are to help, they must address the problem at the appropriately large scale before they can help readers focus on the particular practices to change in any individual business.

To start, one could pair Daniel Yergin’s brilliant 1991 history of petroleum, The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power with Jared Diamond’s Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. It is astonishing to see in The Prize how much of the 20th century’s politics were shaped by the value of oil. Yergin’s book also leads the reader to look at the 21st century with new eyes: No country starts wars anymore, or even shapes its foreign policy, to found new colonies or expand its territory. The one true driver is hunger for energy sources. In Collapse, Diamond analyzes the implosion of societies across continents and millennia — and finds the root cause in resource depletion. Their plight is frighteningly similar to the depletion that the world as a whole seems to be facing today.

A further perspective comes from The World Without Us, by Alan Weisman. Published in 2007, this book is a well-imagined, well-researched look at how Earth would evolve if humans were to disappear from its surface. In New York City, great stone-sheathed buildings are built above tunnels for sewers, heating, and subway trains — most of which would flood the day the great pumps that keep them dry failed. In time the flooded iron would rust, the concrete exfoliate, and the columns buckle. The buildings would fall, and wildlife would return to the streets of Manhattan. Similar fates would befall the great refineries of Texas and other structures around the world, now constantly maintained by humans who deploy abundant fossil-fuel energy to do so. Inside the guise of this compelling hypothetical narrative is an amazingly vivid look at what humanity is doing now to the planet, including dumping millions of pounds of plastics into the oceans, and other actions usually unrecognized in the popular consciousness.

Other sources describe more specific (but still immense) problems that will affect the stability of markets, populations, and governments. Large segments of the world’s population depend on fish for protein, for instance, but many of the world’s fisheries are collapsing, and oxygen-starved “dead zones” are spreading across frighteningly large areas of the oceans. A soil crisis threatens the viability of farming across the globe; the United Nations estimates that 25 million acres of farmland per year are lost to erosion, desertification, and salinization. A water crisis also threatens farming production in many parts of the world, especially in northern China, northern Vietnam, India, and the Sahel of Africa. Meanwhile, the environmentally inspired move toward biofuels is driving up food prices and threatening malnutrition in many nations. No one source covers the full scope of the problem, but there is a body of work, in print and online, that in concert can explain the situation and provide a basis for action.

For instance, Stewart Brand’s Long Now Foundation seminar “City Planet” details the difficult-to-imagine effects of the extraordinarily rapid urbanization of the world — a profound and little-understood change in the environmental future. (Also see “City Planet,” by Stewart Brand, s+b, Spring 2006.)

The problem of collapsing fisheries is covered in Fen Montaigne’s “Still Waters: The Global Fish Crisis,” an article in the April 2007 issue of National Geographic; the technical discussion can be found in the 2004 World Resources Institute report “Fishing for Answers: Making Sense of the Global Fish Crisis,” by Yumiko Kura et al.

To understand the extraordinary size and complexity of the water crisis, see Deep Water: The Epic Struggle over Dams, Displaced People, and the Environment, by Jacques Leslie (Picador, 2006). The details of the fight to save the world’s soil are in Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations, by David R. Montgomery (University of California Press, 2007). The best quick summary and gathering of resources I have seen is a blog post by my son Noah Flower. The group Biofuelwatch maintains a watchdog site on the impact of biofuels. Each one of these problems can in itself destabilize both the political and the natural environment, and they all feed into other problems: Water and soil crises help drive urbanization, rising urban populations strain energy resources, and each connection drives the next.

These problems are almost irreducibly complex, yet managers have to arrive at answers that are simple enough to produce actions: policies, programs, investments, strategies, things that business organizations can do differently. Six books have tackled this challenge, each helpful in its own way.

Plan B’s Impolitic Pragmatism

Lester R. Brown, founder of the Earth Policy Institute, is a living treasure. He has churned out more than 50 books, which have been translated into more than 40 languages, on how to set the world right. His most comprehensive guide, Plan B 3.0: Mobilizing to Save Civilization, originally published in 2003, is now in its third edition. Never afraid to think big and tackle the whole problem, Brown lays out the crises: global warming, soil erosion, energy scarcity, and urban poverty. Then he outlines exactly what to do about all of it. No one, not even Brown, could say whether his analysis or his prescriptions are correct in every detail, but his is the most comprehensive and readable road map to the global crisis and possible solutions.

Brown writes as if he doesn’t care about what is politically feasible, marketable, or easy to fund. He argues convincingly that humanity is rapidly circling the drain of the end of civilization, and compares the current situation to the much simpler task of defeating global fascism in World War II. Nothing less than a similar effort — and certainly not “business as usual” — can stave off the looming disaster.

At the same time, Brown’s proposals are practical, especially compared to the costs of doing nothing. For instance, the proposed budget for “eradicating poverty and stabilizing population” around the world is US$77 billion per year (including such measures as universal primary education and universal basic health care). For “restoring the earth” (including reforestation and stabilization of water tables), the ticket is $113 billion per year. In each category (feeding the world, making cities livable, increasing energy efficiency, and turning to renewable energy), he offers numerous examples of working solutions. Some involve public investments, as when Pennsylvania State University bought free passes for all its students, faculty, and staff on the local city bus line for $1 million per year. Some involve specific changes in policy, such as banning nonrefillable bottles. Many of Brown’s solutions represent business opportunities. For instance, he cites Caterpillar Inc.’s engine remanufacturing division, which recycles old diesel engines into new ones, for generating $1 billion per year in sales and growing at 15 percent per year.

The final chapter, “The Great Mobilization,” includes a clear discussion of shifts in gasoline and other carbon taxes. (See “Pollution, Prices, and Perception,” by Daniel Gabaldon, s+b, Spring 2009.) Brown quotes Harvard economics professor N. Gregory Mankiw: “Cutting income taxes while increasing gasoline taxes would lead to more rapid economic growth, less traffic congestion, safer roads, and reduced risk of global warming — all without jeopardizing long-term fiscal solvency. This may be the closest thing to a free lunch economics has to offer.” This, according to Brown, would be more effective than either bans and regulations or market-based cap and trade schemes — assuming that the political will for such measures can be found.

Advocates for Cap and Trade

Fred Krupp, as president of the Environmental Defense Fund, has long championed the carbon cap and trade idea. Now, with Miriam Horn, he has published Earth: The Sequel — The Race to Reinvent Energy and Stop Global Warming. (See “The Making of a Market-Minded Environmentalist,” by Fred Krupp, s+b, Summer 2008.) Krupp and Horn argue vehemently against regulations that dictate how to achieve environmental goals. They point out, for instance, that the U.S. Clean Air Act, by mandating the use of scrubbers in power plants in the 1970s, stalled research into scrubbing technology for almost two decades. Why should manufacturers refine their technology when industrial companies are required to buy the version they already offer? Schemes that render the desired end (such as less carbon in the atmosphere) into a marketable asset, but that leave the method entirely up to the producers, get much faster, more effective results.

To be sure, cap and trade approaches have some inherent problems; they are by nature easier to game than, for instance, increased taxes on inefficient cars. Krupp and Horn argue that if we use the carbon cap and trade model widely to establish a true market price for despoiling the environment, the technologies waiting in the wings are powerful enough to get us out of this mess.

Perhaps the most valuable part of the book is its thorough tour of the good, bad, and uncertain of those dozens of new energy technologies. These include, respectively, solar cells that convert 42 percent of the sunlight they capture into electricity; corn ethanol (which returns only 30 percent more fuel than it takes to produce it, at the same time driving up world food prices); and underground coal gasification. Some of the most fascinating experiments described in this book include genetically modified yeast that can eat straw, kudzu, or wood chips and excrete “everything we now get from a barrel of oil, ranging from industrial chemicals and plastics to diesel and jet fuel.” The authors describe multiple entrepreneurial endeavors: a company that builds windows that darken in intense sunlight, another business that makes software that powers down idle computers throughout a network, and a construction supply startup (Serious Materials Inc.) that aims to produce cement emitting 90 percent less carbon in its production than conventional cement does.

Not Just Simple Denial

The most intriguing and challenging thinking about energy exists in an intentionally contrarian view that is a must-read for anyone interested in the energy debate: Peter W. Huber and Mark P. Mills’s The Bottomless Well: The Twilight of Fuel, the Virtue of Waste, and Why We Will Never Run Out of Energy. There is plenty to question here, but the authors’ core arguments are original and ultimately compelling.

First, they counter the idea that human energy consumption, in itself, represents a threat to natural life. If it were, they say, we would need to hunker down for some very hard centuries, using not only less energy, but less everything else, since all our “stuff” needs energy in its production, and there are more consumers every year. The effluents of energy production and use — the CO2 and methane, the particulates, the oil spills, the damaged landscapes in West Virginia and Alberta, Canada — are indeed destructive to the environment. But all of them are more or less separable from producing ever more (and more refined) units of energy.

To Huber and Mills, energy itself is far too vague a term. A lump of coal in the ground is not the same as a laser beam. What humanity seeks from energy (and has for more than two centuries) is “more ordered” power — evolving from steam engines to internal combustion engines to turbines, from turning a shaft to moving bits to moving photons. The more precisely controlled the power, the more uses we can find for it. The billions of minuscule bits of energy that move around tiny chips in a cell phone can be used to take photographs, play music, and access the world’s knowledge.

This movement toward more precisely controlled power may well be the primary driver of civilization since the 18th century. It takes power to create more-ordered power, and most of the power used is wasted as heat at each stage of refining and ordering — and the more highly ordered the final product is, the more is wasted.

When fuel costs rise, the authors claim, it’s not because it is getting harder to find oil, but because the growing population of the world and newly burgeoning economies make competition for energy ever stronger. Another factor (especially in the United States and Europe) is the increasing difficulty involved in building new refining capacity or generating plants. And the worry about running out of fuel itself makes the price volatile. New efficiencies in the methods for finding and extracting fossil fuels have outpaced the demand so greatly that bringing oil up through two miles of seawater, four miles of vertical rock, and six miles of horizontal rock today actually costs no more in constant dollars than extracting North Sea oil did in the 1980s, and it costs considerably less than extracting the first Pennsylvania oil did in the 1880s.

The authors also attack the popularity of energy efficiency, on the grounds that it does not necessarily lead to less energy use or to less global warming. With every increase in energy efficiency, people find many more uses for energy. How many of us have left a compact fluorescent lightbulb on overnight because, after all, “it’s only 13 watts”? Or been more willing to drive to a faraway park or resort because, after all, “the Prius gets 50 miles per gallon”? The long history of energy use is one of increasing concentration of energy and increasing efficiency in its use — and increasing numbers of ways to use it, which far outpace the efficiencies.

The Bottomless Well is not a call to complacency. Even if every argument Huber and Mills make is correct, there are still many environmental problems to solve. But even if only the core of their argument is correct, it would help sever the production of ordered power from the despoliation of the planet, both in the public debate and in practice.

Up the Waste Cycle

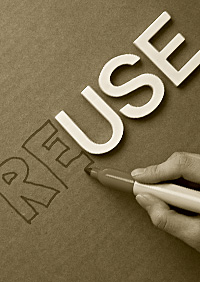

Of course, the ultimate green question for any business is, How do we get smarter at designing, producing, marketing, packaging, and transporting our products? A key guide to thinking about product design is William McDonough and Michael Braungart’s Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. McDonough and Braungart (respectively, an architect and a chemist) argue strongly against the usual “take, make, and waste” product cycle. Even “recycling” fails their test, since almost all products can be recycled only as low-grade reclaimed basic substances, and the recycling process itself consumes a great deal of energy and labor. Instead, the authors advocate “upcycling,” a style of design in which products actually serve as “food” for the next cycle of products.

Cradle to Cradle itself is an example of this approach. The “paper” it’s printed on is a polymer that is infinitely recyclable either in its existing form or as raw material. The nontoxic ink can be washed off with extremely hot water and reclaimed. And the method does not take the form of a compromise or sacrifice: The pages are satiny and white, the print contrast easy on the eyes, the paper waterproof, and the binding and cover stronger and more durable than those of the usual paperback.

Hot, Flat, and Competitive

Aspiration is key to any future that enlists the creative entrepreneurial power of business. That power is not engaged by visions of cutbacks and deprivation. The world’s environmental problems demand solutions with an unprecedented urgency — and every solution will call for vast amounts of equipment, new technologies, evolving and customized designs, and every manner of industrial creativity. Yet the United States has let the lead in many of these niches slip away to Europeans, New Zealanders, and others around the world who have made this work more of a priority.

This is the argument of Thomas Friedman’s new book, Hot, Flat, and Crowded: Why We Need a Green Revolution, and How It Can Renew America. The problem, the New York Times columnist argues, embodies its own opportunity — not only the huge business opportunity represented by rebuilding the energy infrastructure (and much of the physical plant) of the planet, but the opportunity for America to reassert its leadership in the world. (Though its argument could be applied in any country, the book is explicitly aimed at a U.S. audience.) For Friedman, the interconnected global crises are “the epitome of what John Gardner, founder of Common Cause, once described as ‘a series of great opportunities disguised as insoluble problems.’”

Friedman puts the crises in five boxes, and outlines the multiple connections among them: (1) energy supply and demand; (2) petropolitics (the fact that our current “dirty fuel” energy economy props up the worst kind of “petrodictators” across the globe); (3) climate change; (4) energy poverty (the fact that a significant portion of the world’s population is left out of the energy economy); and (5) biodiversity loss. He is cynical about the promotion of recycling and ethanol: “In the green revolution we’re having, everyone’s a winner, nobody has to give up anything, and the adjective that most often modifies ‘green revolution’ is ‘easy.’ That’s not a revolution. That’s a party.”

Unimpressed by “205 Easy Ways to Save the Earth” (the title of a Working Mother article he quotes), Friedman advocates more fundamental shifts in the rules of the marketplace to set off a “forest fire of innovation” to develop new energy sources. He argues that the energy industry puts only 2 percent of revenue back into R&D every year, almost all of it dedicated to expanding traditional sources of supply — not because industry leaders are evil or stupid, but because the market and the tax system allow and encourage them to do so.

He derides cap and trade schemes as a “hide the ball” strategy, and pushes for broad market price signals such as large increases in hydrocarbon fuel taxes; serious, stable incentives for alternative energy investment; and national renewable-energy mandates. He goes on to discuss winning the war on terrorism by “out-greening al-Qaeda” (the U.S. military, it turns out, has a “green hawks” movement); the prospect of competing with China through energy efficiency and green technologies; and a clear discussion of how countries such as Germany, Denmark, Sweden, and New Zealand have driven their alternative-energy sectors with subsidies, tariffs, guaranteed markets, and other incentives.

To people immersed in the subject for years, Friedman’s thesis could seem obvious. But the recent history of the United States suggests that, on this subject at least, it is necessary for skilled, informed, and widely read polemicists like Friedman to write big, bristling books about the insanely obvious and flog them on every talk show.

Industrial-strength Leadership

Meanwhile, thoughtful executives will ask, How can we drive such a fundamental shift throughout our organization? Sustainability is, fundamentally, an issue of organizational development.

One book addresses this question directly, skillfully, and with a wealth of detailed examples from decades of practice: The Necessary Revolution: How Individuals and Organizations Are Working Together to Create a Sustainable World, by Peter Senge et al. Senge, of course, is the author of The Fifth Discipline, a management classic named by the Financial Times as one of the five greatest business books of all time; he was also the founding chair of an international consortium called the Society for Organizational Learning (SoL). This book is the result of years of SoL work helping major organizations “go green” and confront the challenges of a changing natural environment. (See “The Next Industrial Imperative,” by Peter Senge, Bryan Smith, and Nina Kruschwitz, s+b, Summer 2008.) The book features such seemingly improbable examples as the transformative and culturally difficult partnership between the World Wildlife Fund and Coca-Cola, the eco-transformation of Nike, the multifaceted genesis of LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) standards for green buildings, and the way that BMW’s interest in the lifetime eco-footprint of its products led to the E.U.’s “end-of-life vehicles” directive.

In detailed examples, Senge and his coauthors work through difficult questions, such as how to get groups working together toward common goals when they come from radically different cultural backgrounds (Coca-Cola bottlers in Thailand and U.S. not-for-profit wildlife advocates), distinct industry sectors (heating and air conditioning, architecture, materials, civil engineering, and real estate development), or diverse points of view within an organization. They also discuss how to find allies across organizations; how to structure interviews and meetings, balancing advocacy with deliberate listening, to move toward a common vision; and how to help people set aside their prejudgments to hear one another’s actual interests and concerns.

The book is sprinkled with practical “toolbox” sections that feature specific organizational tactics such as “building a sustainable value matrix,” “stakeholder dialogue interviews,” and “guidelines for growing a strategic microcosm.” To the more technically oriented (or the more impatient), such tool sets may seem like a sandbox for the organizational development department. But such a point of view would be deeply mistaken. The core challenges of changing the way the world works are not technical but organizational, cultural, and interpersonal. The Necessary Revolution describes the industrial-strength relationship building, vision articulation, and leadership that the world needs now as it never has before.

All these books and resources, each one in its own way, make it clear that it is time to act. It is not enough to survive the financial crisis, or to keep shareholders and investors happy. We in business are being called to engage with the forces that make life possible. Can we do what’s needed in time? These books start to show us how.![]()

Reprint No. 09110

Joe Flower is a writer and speaker specializing in management, medical, and science issues. A regular contributor to strategy+business, he is also a columnist for Physician Executive and the American Hospital Association’s H&HN Weekly.