City Planet

Get ready for cosmopolitan slums with thriving markets, aging residents, and the most creative economies in history.

(originally published by Booz & Company)“In the village, all there is for a woman is to obeyher husband and family elders, pound grain, and sing. If she moves to town, she can get a job, start a business, and get education for her children.” I heard this remark, made by a global community activist, in 2000 at a Fortune magazine conference in Aspen, Colo. It was enough to explode my Gandhi-esque romantic notions about the superiority of village life.

Data courtesy Marc Imhoff of NASA GSFC and Christopher Elvidge of NOAA NGDC.

Image by Craig Mayhew and Robert Simmon, NASA GSFC.

Ever since, I’ve been asking travelers back from remote places what they noticed out in the countryside. Their universal report: The world’s villages are emptying out, everywhere. People are moving to cities far more rapidly than most of us realize.

Increasing urbanization is accelerating the economic development of the world with remarkable speed. The consequences are going to be profound, particularly for the institutions that serve people — government agencies, corporations, and the creators of infrastructure. Although a growing number of people have noticed the change, few civic and corporate leaders are prepared to deal with it.

The growth of cities has led to demographic trends exactly the opposite of what many experts have predicted. Only 15 years ago, it was widely assumed that the human population would continue to increase exponentially, as it had since the Industrial Revolution. Few experts foresaw the dominant effect that urbanization would have.

But it was obvious by the beginning of the 21st century. “Some 59 countries, comprising roughly 44 percent of the world’s total population, are currently not producing enough children to avoid population decline,” wrote journalist Phillip Longman in Foreign Affairs in 2004. “The phenomenon continues to spread. By 2045, according to the latest U.N. projections, the world’s fertility rate as a whole will have fallen below replacement levels.” In the article (titled “The Global Baby Bust”) and in his subsequent book, The Empty Cradle, Mr. Longman went on to explain the cause: “As more and more of the world’s population moves to urban areas in which children offer little or no economic reward to their parents, and as women acquire economic opportunities and reproductive control, the social and financial costs of childbearing continue to rise.” After I absorbed these ideas, my lifelong worries about population growth, instead of disappearing, reversed. Now I worry about the disruptions of depopulation.

Demographically, the next 50 years may be the most wrenching in human history. Massive numbers of people are making massive changes. Having just experienced the first doubling of world population in a single lifetime (from 3.3 billion in 1962 to 6.5 billion now), we now are discovering it is the last doubling. Birthrates worldwide are dropping not only much faster than expected, but much further. It used to be assumed that birthrates would get down to the replacement rate of 2.1 children per woman and level off, but in most places the birthrates continue to decelerate with no bottom in sight. Meanwhile the “population momentum” of the already born and their children will carry world population to a peak of 7.5 to 9 billion around 2050 and then head downward.

Even those who note the trend correctly tend to think of it as a developed-world phenomenon: “aging Japan” and “senescent Europe.” Indeed, the long-urbanized developed nations have an average birthrate of 1.56 children per woman, and in some places the rate is as low as 1.3. Those are radical depopulation numbers. It is already in the cards that Russia, Japan, Italy, Spain, and Germany will have fewer people in 2050 than they do now. And by then the majority will be old, past childbearing. Just as the population exploded upward exponentially when the birthrate was above 2.1, it accelerates downward exponentially when it’s below 2.1. Compound interest cuts both ways. Fewer children make fewer children.

But the main event of the demographic circus is in the cities of the developing world — and most of it in squatter cities, the teeming slums of the uninvited. A billion people live in squatter cities now. Two billion more are expected by 2050. Squatters are nearly one-sixth of all humans now, one-fourth to one-third pretty soon.

Already, as a result of the headlong urbanization, birthrates have plummeted in the developing world from 6 children per woman in the 1970s to 2.9 now. Twenty “less developed” countries, including China, Chile, Thailand, and Iran, have already dropped below the replacement rate of 2.1 children per woman.

And what about the young and fertile couples in developing countries? If current demographic trends continue, 2 billion of them will live in the cities, choosing to have fewer children. It’s not because they’re poor. They were poor in the countryside. In town they see opportunity to come up in the world. Having fewer children, who are better educated, is part of that equation.

The long-anticipated “demographic transition” is happening now, sooner and more rapidly than expected, and it’s a world-changer. First, the cities of the developing world will see dramatic population increases over the next 30 years. An equally dramatic maturing of their population will quickly follow as migration levels off and the urban birthrate drops. No one knows what, if anything, will forestall the depopulation trend in this century, but then no one predicted that the population explosion would be leveled off mainly by people moving to cities.

Meanwhile, this overwhelming demographic shift is only one of the changes in store from the new cities of this century. As cities always do, they will foster new forms of culture and technology, and they will lead to often surprising shifts in business and trade patterns. The proposed solutions to most of the problems of the world — and the problems of individual enterprises — will either take hold or wither depending on their success or failure in cities.

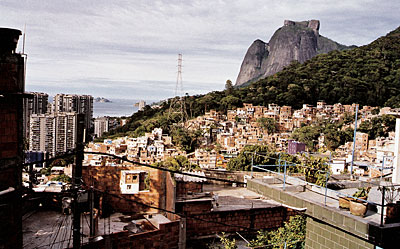

View from a balcony in Rocinha, Brazil, a dense and relatively prosperous squatter community of 150,000 people, built on steep hills above Rio de Janeiro

Urban Legions

Every week 1.3 million new people arrive in the world’s cities (about 70 million a year). It is the largest movement of humanity in history, one that started at least 100 years ago and is still accelerating. Signs are that the flood will continue for decades.

Three percent of humanity was urban in 1800, 14 percent in 1900. Sometime in 2006 or 2007 the proportion of urban dwellers will pass 50 percent worldwide, which may represent an economic tipping point. United Nations projections put the world’s city dwellers at 61 percent in 2030, continuing upward to an expected equilibrium in which, at any given moment, only about 20 percent of the population will live in rural areas, balanced against an 80 percent urban majority. The transition point from a “developing” to a “developed” country seems to occur when the country becomes 50 percent urban. (Most developed nations arrived at that point and their present state of about 75 percent urbanization much more gradually than the developing nations currently undergoing breakneck growth in cities.) In that light, Earth as a whole is just now becoming a developed world — a city planet.

Cities are remarkable organisms. They are the most long-lived of all human organizations. The oldest surviving corporations (Stora Enso in Sweden and the Sumitomo Group in Japan) are about 700 and 400 years old, respectively. The oldest universities (in Bologna and Paris) have lasted a thousand years. The oldest living religions (Hinduism and Judaism) date back about 3,500 years. But the town of Jericho has been continuously occupied for 10,500 years. Its neighbor Jerusalem has been an important city for 5,000 years, though it was conquered or destroyed 36 times and it suffered 11 conversions from one religion to another. Many cities die or decline to irrelevance, but some thrive for millennia.

Perhaps one cause of their durability is that cities are the most constantly changing of organizations. In Europe, cities replace 2 to 3 percent per year of their material fabric (buildings, roads, and other construction) by demolishing and rebuilding it. This means, in effect, that a wholly new city takes shape every 50 years. In the U.S. and the developing world, that turnover occurs much faster. Yet within all that turnover something about a city remains deeply constant and self-inspiring. Some combination of geography, economics, and cultural identity ensures that even a city destroyed by war (Warsaw, Tokyo) or fire (London, San Francisco) will often be rebuilt.

A hundred years ago, the biggest cities were almost all in the West — London (7 million in 1900), New York, Paris, Berlin. These days there are 428 metropolitan areas with more than a million inhabitants. The top 10 list now reads: Tokyo (34 million), Mexico City, Seoul, New York, São Paulo, Mumbai (formerly Bombay), Delhi, Los Angeles, Jakarta, and Osaka (Japan, 16.7 million). Barging into the top 10 by 2015, according to U.N. demographers, will be Lagos (Nigeria), Dhaka (Bangladesh), and Karachi (Pakistan).

One of the few popular writers studying the phenomenon is Mike Davis, a recipient of a MacArthur “genius” grant who wrote brilliant muckraking analyses of Los Angeles in City of Quartz and Ecology of Fear. Turning his attention to cities in the developing world, he writes in his forthcoming book Planet of Slums (Verso, 2006), “In Africa…the supernova-like growth of a few giant cities like Lagos (from 300,000 in 1950 to 10 million today) has been matched by the transformation of several dozen small towns and oases like Ouagadougou, Nouakchott, Douala, Antananarivo, and Bamako into cities larger than San Francisco or Manchester. In Latin America, where primary cities long monopolized growth, secondary cities like Tijuana, Curitiba, Temuco, Salvador, and Belém are now booming, [in the words of demographers Miguel Villa and Jorge Rodriguez] ‘with the fastest growth of all occurring in cities with between 100,000 and 500,000 inhabitants.’” In other words, more and more significant news will be coming from cities most people in the West have not yet heard of.

Demographers talk about “push” and “pull” motivations driving the huge migration to the cities. Push feels like this: Life in your village is dull, backbreaking, impoverished, restricted, exposed, dangerous, and static. In the countryside, you are at the mercy of bad weather, bandits, and disease, with nowhere to go for help. But visit your relative in town and you see what “pull” means. In the city, life is exciting, less grueling, far better paid, free, private, safe, and upwardly mobile. Will you put up with slum conditions for all that? In a heartbeat. “City air makes you free,” said the Renaissance Germans. History may view the European Renaissance as mild compared to the change going on now.

“Pavement dwellers” living in open-air homes in Byculla, a Mumbai neighborhood

Squatter Vibrancy

Let no one romanticize the conditions of slums. New squatter cities usually look like human cesspools and often smell like them. There is usually no infrastructure at all for sanitation, for water, for electricity, or for transportation. Everyone lives in dilapidated shacks jammed together wall to wall, with every room full of people. A typical squatter city, which may stretch for miles, has grown without a plan or government, in an area generally deemed uninhabitable: a swamp, a floodplain, a steep hillside, a municipal dump; clustered in the path of a highway project, squashed up against a railroad line.

But the squatter cities are vibrant. Each narrow street is one long bustling market of food stalls, bars, cafes, hair salons, churches, schools, health clubs, and mini-shops of tools, trinkets, clothes, electronic gadgets, and pirated videos and music. What you see up close is not a despondent populace crushed by poverty but a lot of people busy getting out of poverty as fast as they can.

Considered together, squatter cities are the scene of an enormous economic event, but it escapes notice because it’s designed to escape notice. Squatters don’t formally own land or property. They don’t pay taxes. They take no part in any permit or licensing process. They pay no attention to government-approved exchange rates. And yet they thrive economically, charging each other rent for space in unowned buildings, employing each other in their unlicensed businesses, and selling each other all manner of goods and services. This is what is called the informal economy, and it is to economic theory what “dark energy” is to astrophysical theory. It’s not supposed to be there, but it is, and it is huge. How else do we explain slum-laden Mumbai (half of its 12 million residents are squatters) accounting for one-sixth of India’s entire GDP? Its actual impact on the economy is probably greater still, because GDP figures don’t typically reflect the full value of the underground economy.

Two recent books have penetrated the clouds of wrong theory about squatter cities because the authors spent time actually living in the shantytowns. The books are The Challenge of Slums, the 2003 global report by the United Nations Human Settlements Program, and Shadow Cities: A Billion Squatters, A New Urban World, by journalist Robert Neuwirth (Routledge, 2004). The U.N. book is based on 37 case studies conducted all over the world. Robert Neuwirth did his research by learning the relevant languages and then living for months as a resident in Rocinha (one of 700 favelas, or shantytowns, in Rio de Janeiro); in Kibera (a squatter city of 400,000 adjoining Nairobi); in the Sanjay Gandhi Nagar neighborhood of Mumbai; and in Sultanbeyli, a now fully developed squatter city of 300,000 with a seven-story city hall, next to Istanbul, Turkey. (If you want a vivid film experience of real squatter cities, see the work of Brazilian film director Fernando Meirelles. His City of God takes place in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, and much of last year’s The Constant Gardener was shot in Kenya’s Kibera district.)

Contrary to a common assumption, the U.N. researchers and Robert Neuwirth found that the wretched quality of housing in squatter cities is never the main concern of the inhabitants. Indeed, when governments and idealistic architects provide public housing, those buildings often turn into the worst part of the slums. The people who build the shanties take pride in them and are always working to improve them. The real issues for the squatters are location — they want to be close to work — and what the U.N. calls “security of tenure.” They need to know that their homes and community won’t suddenly be bulldozed out of existence.

Another piece of conventional wisdom that turns out to be wrong concerns crime. Far from being the hotbeds of criminal activity that everyone assumed, the squatter cities are often victimized by criminals from outside, because they have no protection by government police. (The exception is in Brazil, where the favelas are the safest areas in Rio, thanks to drug gangs taking on the role of community police; in the absence of government police, they enforce their own stronger version of public security.)

Squatters are tremendously resourceful and productive. In aggregate they are the dominant builders in the world today. They will do much of the work and innovation of building the cities of the 21st century and the global urban economy. All that the keepers of the formal economy have to do is meet them halfway — help them secure their tenure and give them time to gradually join the formal world, which will no doubt be reshaped by their joining it.

Though the squatter communities have what the U.N. researchers describe as “cultural movements and levels of solidarity unknown in leafy suburbs,” they are seldom politically active outside the defense of their own community interests. Nevertheless, governments sometimes fear their solidarity, and that’s why the bulldozers are sent, as in Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe, to eliminate squatters (thereby helping commit national economic suicide). According to the U.N., three-quarters of all countries with large urban squatter populations have programs to keep people back in the countryside, and all are failing. That is fortunate.

Squatters’ homes near Istanbul, Turkey; the rebar allows for expansion

Migrant Boomers

Gradually a consensus is emerging about the economic value of rural-to-urban migration. This migration, “on the whole, acts to alleviate poverty in both the urban and rural sectors,” wrote geography professor Ronald Skeldon in 1997. He explained that the urban “informal sector, with its capacity to create an almost infinite variety and number of activities” and its “considerable potential for self-organization…can create a dynamic economy and society.”

The 2003 United Nations report on slums is yet more optimistic. The authors estimate that 60 percent of urban employment in the developing world is in the informal sector, and it has essential links to the success of the formal sector: “The screen-printer who provides laundry bags to hotels, the charcoal burner who wheels his cycle up to the copper smelter and delivers sacks of charcoal…the home-based creche to which the managing director delivers her child each morning, the informal builder who adds a security wall around the home of the government minister all indicate the complex networks of linkages between informal and formal.”

Unemployment rates, the U.N. report notes, are irrelevant in an economy that is largely informal, “because virtually everyone (including children) is involved in a number of economic activities in order to live, and the conceptual separation of workers and non-workers is meaningless.” Also meaningless is the separation of production and consumption when a family’s business is home-based. Some workers who have gathered skills and savings in the formal economy use them to set up shop in the informal world: “By adopting the triple role of entrepreneur-capitalist-worker, they can achieve total incomes greater than comparable waged workers in the formal sector,” the U.N. report asserts.

Squatters bring rural skills and values to town with them. Building their own shelter is what they’ve always done, at a minute fraction of the cost of city-provided housing. Collaborating with extended family and neighbors in close proximity is nothing new to them, and neither is doing without elaborate infrastructure.

Social cohesiveness is the crucial factor differentiating “slums of hope” from “slums of despair.” This is where CBOs (community-based organizations) and the NGOs (nongovernmental organizations) that support local empowerment play such an important part. Typical CBOs include, according to the 2003 U.N. report, “community theater and leisure groups; sports groups; residents associations or societies; savings and credit groups; child care groups; minority support groups; clubs; advocacy groups; and more.… CBOs as interest associations have filled an institutional vacuum, providing basic services such as communal kitchens, milk for children, income-earning schemes and cooperatives.”

Cities have been the wealth engine for civilization since its beginning. Thus the bottom line in the U.N. report: “Cities are so much more successful in promoting new forms of income generation, and it is so much cheaper to provide services in urban areas, that some experts have actually suggested that the only realistic poverty reduction strategy is to get as many people as possible to move to the city.”

The role of women in all this cannot be overemphasized. The U.N. report notes that CBOs “are frequently run and controlled by impoverished women and are usually based on self-help principles, though they may receive assistance from NGOs, churches and political parties.” One of the major effects of the move from country to city is the unleashing of woman power. Experience shows that microfinance credit works better when provided to women, not men, and women are the more responsible holders of property deeds. The U.N. report summarizes: “In many cases, women are taking the lead in devising survival strategies that are, effectively, the governance structures of the developing world when formal structures have failed them. However, one out of every four countries in the developing world has a constitution or national laws that contain impediments to women owning land and taking mortgages in their own names.”

It is so important to free up newly urbanized women from their traditional role as fetchers of water and fuel that the U.N. report dryly recommends, “The provision of water standpipes may be far more effective in enabling women to undertake income-earning activities than the provision of skills training.”

The significance of religious groups also cannot be overemphasized. According to Mike Davis, “Populist Islam and Pentecostal Christianity (and in Bombay, the cult of Shivaji) occupy a social space analogous to that of early twentieth-century socialism and anarchism. In Morocco, for instance, where half a million rural emigrants are absorbed into the teeming cities every year, and where half the population is under 25, Islamicist movements like ‘Justice and Welfare,’ founded by Sheik Abdessalam Yassin, have become the real governments of the slums: organizing night schools, providing legal aid to victims of state abuse, buying medicine for the sick, subsidizing pilgrimages and paying for funerals.” He adds that “Pentecostalism is…the first major world religion to have grown up almost entirely in the soil of the modern urban slum” and “since 1970, and largely because of its appeal to slum women and its reputation for being colour-blind, [Pentecostalism] has been growing into what is arguably the largest self-organized movement of urban poor people on the planet.”

As the cities of the next 20 years evolve, they will increasingly bargain with the older cities, and with corporations, as equals. What will that bargaining look like?

Kibera, a neighborhood of mud huts outside Nairobi, Kenya, where more permanent structures are illegal for squatters

Aspirational Shantytowns

To me the most compelling image of hope in squatter communities is something you see everywhere — masonry and concrete building walls with rebar sticking out of the top. The rebar — reinforcing bars of steel — is there as an anchor for a potential new wall, in the expectation that eventually, when there’s enough money, another story will be added to the building. It may provide more living space for the family or another source of rent. The magic ingredient of squatter cities is that they are improved steadily and gradually, increment by increment, by the people living there. Each home is built that way, and so is the whole community.

Another common sight in squatter towns is a network of wires strung everywhere, carrying pirated electricity and cable TV, and pipes snaking in all directions, illegally distributing water. In Brazil, a country with a good reputation for helping squatters, Mr. Neuwirth reports that the cable, power, and water companies decided to stop treating the gatos (“cats,” the squatters who siphon off public services) as thieves and instead treated them as people trying to become customers. Working with the communities, sometimes through nonprofit organizations, they are gradually improving the infrastructure and building revenue in cahoots with a particularly entrepreneurial new customer base.

Over time, usually decades, squatter cities become real cities, part of the formal economy. Mr. Neuwirth points out that all of the world’s present major cities began as disreputable shantytowns. Step-by-step, the new towns will join the global economy that caused them in the first place. It was the industrialization of agriculture for global markets that reduced the rural jobs. Global corporations often provide the best-paying jobs and best working conditions in town, raising the standard for everyone. Global NGOs, having learned to distrust national governments, go straight to the burgeoning new cities, where the neediest can be served most directly. The “agglomeration economies” that make cities wealth producers are accelerated, and in turn they speed the global economy.

It’s easy to gloss over the enormous variety among the thousands of emerging cities with different cultures, nations, metropolitan areas, and neighborhoods. From that variety is emerging an understanding of best and worst governmental practices — best, for example, in Turkey, which offers a standard method for new squatter cities to form; worst, for example, in Kenya, which actively prevents squatters from improving their homes. Every country provides a different example. Consider the extraordinary accomplishment of China, which has admitted 300 million people to its cities in the last 50 years without shantytowns forming, and expects another 300 million to come.

The new levels of communication and trade linkage worldwide mean that every city of size becomes in effect a world city, with the accompanying multipliers of cultural diversity, financial flow, and people flow. In the vast worldwide migration toward jobs, the poor hardly limit themselves to cities in their own countries. There is also a large population of global urbanites who live at large, at home not in any one locale but “in cities.” These peripatetics include thousands of professionals and many of the world’s wealthy. We’re still discovering how the totality of an urbanized world will differ from our experience of urbanized nations and regions.

How does all this relate to businesspeople in the developed world? One-fourth of humanity trying new things in new cities is a lot of potential customers, collaborators, and competitors. C.K. Prahalad’s book The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid (Wharton School Publishing, 2005) spells out how companies can reach the poor and deliver goods and services at the interface between the formal and informal economies. Those concerned about widespread piracy of intellectual property (such as music, movies, books, software, and brand names) in emerging-market cities may want to follow the example of the Rio water and power companies and find ways to treat the pirates as people trying to become customers. The world should be attuned to what is going on in the squatter communities, because more than just music is coming out of them. Lively new forms of self-organizing behavior are taking shape there.

For environmentalists, the massive urbanization could represent a huge opportunity, though most haven’t realized it yet. The “ecological footprint” of cities is indeed large (and well studied), but the per-person environmental impact of city dwellers is generally lower than that of people in the countryside, and it can be made lower still. In many regions the emptying of the countryside means that the pressure on natural systems is suddenly reduced. Replacing the widespread subsistence farmers and herders, who treated wild animals as pests or food and wild trees and shrubs as firewood, is efficient industrialized agriculture in more localized areas (with less herbicide and pesticide impact thanks to genetically modified crops). The trees and wild animals are coming back. Now is the time to set in place protection for the rural natural systems, so when people return, as they surely will, the places they return to will be on a path of increasing biodiversity and health.

As reflected in the United Nations’ “Green Cities Declaration” last year, a worldwide movement is under way to reshape cities toward better ecological and economic fitness. The “new urbanists” rightly push for dense, mixed-use urban forms (articulated in a vocabulary of lot sizes, building shapes, use mixes, and code nuances), plenty of mass transit, and limitations to diffuse sprawl. I would like to see ecological-footprint analysis of squatter cities, with their extreme density, low energy use, and ingenious practices of recycling everything. Maybe there are ideas there that could be generalized.

What the world has now is new cities with young populations and old cities with old populations. How the dialogue between them plays out will determine much of the nature of the next half century. The convergence of the two major trends, globalization and rampant urbanization, means that all cities are effectively one city now.

The demographic literature refers often to the “bright lights” phenomenon that draws people to cities. People want to be where the action is. Thanks to satellite imagery, those lights and that action are now visible from space. The night side of the Earth, these decades, displays dazzling webs of light, with incandescent nodes at all the metropolitan areas and a bright tracery of transportation corridors between them. That web of light is the sign to visitors that they are approaching not just a living planet, but a civilized planet.![]()

|

Mumbai Highway |

|

I wish to offer five perspectives, influenced by my experiences as a marketer in a consumer goods company (Hindustan Lever Ltd.) for three decades and working in a large industrial conglomerate (the Tata Group) for eight years after that. 1. Political and business leaders are already changing their attitudes about the legitimacy of squatter cities. Even 50 years ago, Dharavi in Mumbai might well have been the world’s biggest slum, largely settled by Tamils and Telegus from southern India. It has even produced one of the well-known dons of crime, Varadaraj Mudaliar, a character who has inspired a major Bollywood film (Nayakan, directed by Mani Ratnam). As a young sales manager marketing to grocery shops in urban slums, I used to wonder how these slums could possibly survive. At that time, Mahatma Gandhi’s view seemed to be right: He had advocated keeping people in the rural areas by promoting the charkha, the village spinning wheel. Today, Dharavi is brimming with entrepreneurship. It boasts households with television sets, shops selling mobile telephones, and restaurants serving multiethnic cuisine. It is no longer “illegitimate” in any way. Civic amenities like bus service, schools, and hospitals took several decades to come, but they exist now. Many political leaders, over the past 50 years, have contemplated stopping urban migration through regulation: for example, by monitoring entry into Mumbai. Leaders now realize that this will not work; they should manage the situation rather than attempt to eliminate it. In November 2005, Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh said in Delhi, “Urban areas are the nodes from which enterprise, creativity, and prosperity radiate in all directions.… We need a new wave of city buildings for the 21st century.” China’s leaders are thinking similarly. As the Financial Times noted on November 15, 2005: “Beijing aims to manage, rather than halt, rural migration which it accepts is important for economic growth.” 2. The new cities represent a new kind of global melting pot. People of different regions, subcultures, and even nationalities constitute an invisible and uncontrollable proportion of the immigration wave. Rural Bangladeshis, for example, are enticed by organized syndicates, which operate over the 4,000 kilometers from Kolkata to Mumbai, to cross the porous border in Bengal to seek a livelihood in the burgeoning Indian cities. In a multilingual country like India, the “real” language spoken among the slum-dwellers is invariably not the local one (Marathi in Mumbai) but one from elsewhere (Tamil, Telegu, Hindi, or Bengali). All of them are commingling in the urban slum population. As all these people mix, the economic vibrancy of the urban slums is providing an escape valve for the pressures and tensions of inequality. Economist Albert Hirschman likened a society with recognizably distinct groups to a multilane highway. If none of the lanes is moving, then people will sit through a traffic jam patiently. However, if one or two lanes are moving faster and they see no hope of a movement in their own lane, then they will jump lanes. History shows that great disparities in wealth cause economic depression, and in repressed political situations, even revolutions. A release mechanism for inequality is best found before the pressure becomes unmanageable. Informal-sector employment and entrepreneurship in the urban squatter cities represent a short-term solution. But will that be enough in the long run to absorb enough people into the formal economy and society with dignity and opportunity? Or will some kind of intervention, from either the government or the private sector, inevitably be called for? 3. One should not judge squatter colonies and urban slums by the standards of the urban rich. I used to think that people would quit the slums with the slightest inducements from government. Even today, if a person like me visits there, the situation appears intolerable. And urban planners continue to think that rehabilitation apartments are a solution. But they are not. Journalist Suketu Mehta captures the reason in this passage from his book Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found (Knopf, 2004): “I asked…if she wouldn’t rather live in a decent apartment.… She replied, ‘There is too much aloneness there, a person can die behind closed doors of a flat and no one will know. Here there are a lot of people.’” 4. Because squatters are real consumers with real needs to be satisfied, they represent an opportunity. Companies have learned to design their products by comprehending the needs of such consumers. They live on an economic escalator; if a company can connect with them early on, there are legitimate business rewards to be reaped in the course of time. They provided my company with a market for consumer goods — a large and attractive one. Initially, my company did not sell them Lux, “the bathing soap of the film stars,” but sold them Lifebuoy, “the soap that washed away germs.” Today, those consumers buy Lux, and even more expensive soaps. In the early 1970s, they had no running water in their dwellings, so they could not use synthetic powdered detergents — there was no receptacle to soak their clothes in, let alone the water to rinse after the soak. My company designed a synthetic detergent bar called RIN, one of the first such bars in the world, so consumers without access to large quantities of running water could wash by rubbing the clothes. Such soaps are flourishing consumer products today. It is the same story with shampoos, TV sets, bicycles, and two wheelers, electric bulbs, and even banking. Microcredit — the use of pooled credit to help lower-income people start businesses and find opportunities — is no longer just a rural phenomenon. There is an association of Indian microcredit lenders, and its members feel that the conditions of growing urbanization today represent “the big moment; it couldn’t be bigger.” The central bank of India promotes this idea, on the grounds that microcredit helps the poor, but it also allows banks to increase their business, enhance their profit, and spread the risk. A recent World Bank report indicates the growth potential in India by pointing out that microcredit touches only 5 percent of the poor. In Bangladesh, microcredit touches two-thirds of the poor. 5. Asians should not be too complacent; we Asians will also face the problems of an aging population. China and East Asia’s working-age population will peak in 2010; India’s will peak about 30 years later. Thereafter, there will be progressively fewer consumers (as is the case in the West and Japan already) but, more importantly, the number of pensioners will increase without an increase in the working population. This will have an adverse effect on market sizes and cost structures in geometrical progression, just as the beneficial converse happened in the earlier phase when the working population increased. For India, there may actually be a demographic bonus between 2010 and 2040, when its working population is still increasing, while populations in the rest of Asia level off and decline. The rabbit is in the middle of the python, and because the process of depopulation will happen over 30 years, the subject does not engage much of the attention of Asian corporate leaders. But it will. R. Gopalakrishnan (rgopal@tata.com) is the executive director of Tata Sons, the holding company of the Tata Group, India’s largest industrial conglomerate. |

|

Tomorrow’s Markets |

|

For those focused on building the markets of tomorrow, the visible poverty and squalor of the “city planet” hides a less visible reality. Whether located in São Paulo, Mexico City, or Mumbai, any emerging shantytown is a vibrant economic hub. The people who live there have the same aspirations as the urban rich and brand-conscious middle class. They are tomorrow’s market for televisions, cell phones, pharmaceuticals, and video games. They are also entrepreneurs. For example, in Dharavi, one of the largest shantytowns in India, local manufacturers make leather goods (jackets, wallets, handbags), gold jewelry, packaged food, recycled plastic (which they sell as raw material), and medical supplies. There are one- to two-person entrepreneurial shops, and well-organized workshops employing 50 to 100 people. Unfortunately, this emerging, vibrant economic hub of consumers and producers tends to exist in what is called the extra-legal or unorganized sector. These terms are often used to dismiss this sector’s importance. But they simply indicate that the sector is not part of the formally recognized economy of the country. It is important for governments to recognize these emerging hubs of economic activity and make it easier for them to become integrated with the formal economy. Large firms can help in this process. For example, banks can simultaneously double their customer base (if not assets under management) and learn how to provide world-class financial services at low cost. The opportunity for “doing well by doing good” for global firms is considerably enhanced by the urbanization of developing countries. The poor are voting with their feet. They seek market-based work opportunities for themselves, through proximity to higher-paying nonseasonal and nonagricultural employment; and they seek opportunities for their children to escape the “poverty trap.” Because of the negative side of this urbanization process — congestion, pollution, shantytowns, transportation bottlenecks, and crime — some critics argue that we have to stop this trend. But with imaginative public–private–civil society partnership, this trend can lead to a new approach to eradicating poverty through social and business innovations. |

Reprint No. 06109

Stewart Brand (sb@gbn.org) lives in a squatter houseboat community in Sausalito, Calif. He is the founder of the Whole Earth Catalog and a cofounder of Global Business Network. His books include The Clock of the Long Now (Basic Books, 1999), How Buildings Learn (Viking, 1994), and The Media Lab: Inventing the Future at M.I.T. (Viking, 1987).