Closing the Awareness Gap in Technology Projects

Even the best digital fixes sometimes fail, but focusing on nontechnical factors can ensure your investment pays off.

What’s your most pressing business problem right now? Perhaps you want better visibility along your supply chain, and you’re trying to accomplish this with a new data analytics system. Maybe you’re planning a major capital project, and you’d like to make more sense of all the construction data you’re receiving so you can react quickly to signs of cost or schedule overruns. No matter the specifics, the larger problem probably involves trying to tailor digital technology and analytics to your company’s needs.

Typically, to solve these sorts of problems, you delegate them to your IT department, which identifies a technology it believes will fill fix everything. You know it’s common for enterprises to spend heavily on technology to gain visibility and insights that are supposed to lead to results. At the outset, there’s usually a clear and sensible rationale for adopting this particular technology, based on benchmarking. It’s already popular in your industry. Implementation is tricky, as it usually is, but in the early stages the technology looks to be working as it should.

Then something strange occurs. Despite all this new data you have, your supply chain continues to be less efficient than those of the market leaders. Your capital projects still fall behind schedule and break their budgets. After all this investment, effort, and attention, your problem remains unresolved.

What has gone wrong? If you have implemented the same technology as the leaders in your industry, why can’t you perform like them?

The answer, almost always, is that you have misdiagnosed your problem as an operational challenge to be solved with a technological fix. When you use data in new ways to increase your understanding, yet your technology fix does not cure what ails your company, the real culprit is likely an awareness problem. And the real solution involves thinking in new ways about your strategy, about the experience of the employees who implement this strategy, and about the type of data you will need.

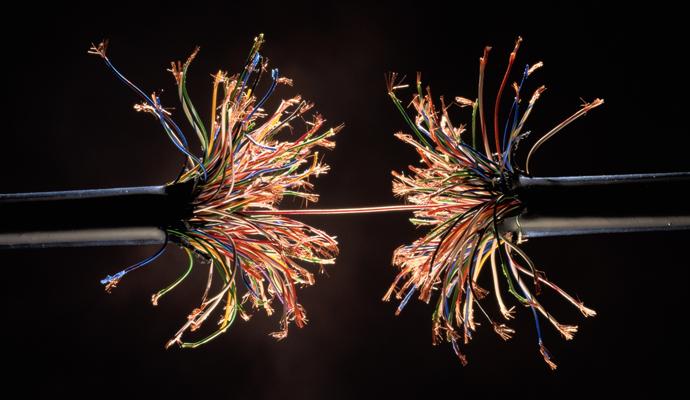

For example, we’ve seen enterprises build fabulous supply chain control towers: central hubs equipped with magnificent software, sensors, and drones to gather, process, and analyze data. But the functional links in the chain that use this data — planning, production, procurement, suppliers, logistics, customer delivery and service teams, and even customers — have no easy way to share their analyses or communicate with one another about them. And even if everyone can communicate, they may not want to. Many suppliers and contractors might fear that the added costs of gathering, standardizing, and confirming data will bring down their margins. They also might not want you to spot problems in their work or provide you with information that could undermine a negotiating position down the road. To really get the performance gains you seek, you have to become aware of these subtle tensions and inconsistencies, and incorporate that awareness in the design of your solution.

Whether it’s a supply chain, a capital project, or some other part of your operation, your goal is to make your organization more aware of the ongoing results of everyday decisions, so you can continually improve those results. Technology alone, which is always available to all your competitors, will never accomplish this by itself.

Designing for Awareness

The symptoms of a problem with operational awareness can vary. Sometimes you fail to obtain visibility at the level of accuracy you need; sometimes you get that visibility, but don’t know how to act on it; sometimes, even when insights lead to actions, these actions fail to lead to your desired results. If you’re trying, for example, to reduce time delays, your data analytics might show which parts of your project are moving more slowly than expected, but they’re unlikely to pinpoint the precise reason. Problems in one place might be the result of decisions made several steps back in the supply chain or project life cycle. Was planning off? Did procurement write a poor contract? Maybe your workers lack the necessary skills?

No matter how sophisticated artificial intelligence becomes, we believe it will never replace the kind of ingrained, comprehensive awareness that people develop when the right data and tools are available.

The experience of using the system may also make it difficult for you and your employees to make sense of the data effectively. For example, in our work with boards of directors, who are taking (with good reason) a growing role in overseeing high-value projects, we sometimes observe members relying heavily on dashboards or documents developed with sophisticated data analytics. These presentations may show that the new power plant, data center, oil rig, or factory is advancing beautifully. The style may be rich, but it can distract you from the quality of the data, or make it harder to see more subtle problems and opportunities. And even if you spot a problem, the interface and implementation of such a presentation could move you toward complacency — a point at which, say, a team produces a slideshow explaining why cost overruns are justified.

It takes a different kind of technological design to gain in-depth, real-time data awareness. To get past shiny, algorithm-driven presentations and simulations that can lull you into a false sense of security, you need to approach your analytic design with the same type of perspective that you expect the new analytics to give you. Here are the steps successful companies take when deploying new technologies to build awareness into their designs.

Bring together the right type of design team. Include not just technologists, but people who keenly understand the business and the value of user experience. Assume no handoffs: The team will come together to intensively design the system as a single group. With this type of process, and the right team members, you can create an advanced system in a relatively short time.

Start with the true end goal. As you consider technology for a particular project or stage of operations, focus on its ultimate purpose. What will the data you gather be used for? To understand your supply chain operations? Innovate more quickly and productively? Create greater transparency? Expand your customer base? You should follow an approach such as the “Five Whys,” a long-standing Japanese management technique that helps you dig into the underlying drivers of surface problems. Ask a series of at least five “why” questions. For example, why do you want to improve supply chain operations? To gain speed and efficiency? Why do you want that? And so on.

Focus on human experience. Once you’ve identified the business end goal, think about what happens when employees log in to use the data. Is the system clear and easy to follow? Do people like using it? Does the experience make users wiser and more competent at seeing patterns that will lead to better decisions about, say, project maintenance or supply chain efficiency? For example, before you install a new supply chain control tower, the system should map the supply chain end to end, so you can see more clearly where performance deficiencies occur.

Get all (or most) of the relevant data. If you fail to gather and secure the data you need, you run the risk of making error-driven decisions. Don’t just incorporate data you are already gathering. Use technological advances, such as drones, Internet of Things sensors, and online behavior, to add to the data you already have. Create incentives and opportunities, perhaps embedded in your contractual frameworks, for your suppliers and other business partners to share data with you. Ensure data discipline and transparency in your oversight.

Align metrics and governance structures to this new system. Set data and security standards, define roles and responsibilities, and be sure that incentives and metrics for different functions — or different organizations — are aligned. In a capital project, for example, to support a goal of reducing project costs or delays, you’ll want to measure productivity with metrics that track the cost of labor against achieved progress. To be accurate, these metrics will have to account for the different requirements of the project’s various components, as well as the likely use of multiple contractors and subcontractors. Otherwise, some areas may appear more or less productive than they really are.

Calling on Humans and Robots

No matter how sophisticated artificial intelligence becomes, we believe it will never replace the kind of ingrained, comprehensive awareness that people develop when the right data and tools are available to them. To be sure, machine learning–based systems will do more and more on their own, generating increasingly sophisticated analyses based on far greater amounts of data, yielding unprecedented solutions and perspectives. It may soon be possible to automate activities on the fly: Put this contract on hold for review, send over more drones for a better look, reroute shipments.

But when it comes to the heart of strategy — setting priorities, choosing the metrics that matter, incentivizing people, and overseeing the complexities of a supply chain or a capital project — we’ll always need humans. In fact, in this new and more sophisticated world, the real breakthrough isn’t in our relationships with machines. It’s in our engagement with more and more people, using technology to help us ask and answer questions together, and take part in designing ever more productive solutions.

Author profiles:

- Daryl Walcroft leads the U.S. capital projects and infrastructure practice for PwC, advising clients as they plan and carry out complex, large-scale initiatives. Based in San Francisco, he is a principal with PwC US.

- Robert DeNardo is a leading practitioner in supply chain strategies for Strategy&, PwC’s strategy consulting business. He has extensive expertise in end-to-end supply chain transformations. Based in Chicago, he is a principal with PwC US.