Doing the right deals

How corporate leaders can avoid value-destroying M&A.

How do leaders make deals work? How do they ensure that the resources they invest—often at a premium to market value—produce worthwhile returns? We know from our body of research that one of the factors that differentiate successful deals is the same powerful factor that differentiates successful companies: a strategy rooted in capabilities. These are the specific combinations of processes, tools, technologies, skills, and behaviors that allow companies to deliver unique value to their customers. Think about Apple’s design capability, Amazon’s retail interface design, or Frito-Lay’s rapid flavor innovation.

As we’ve been highlighting for some time, capabilities-driven companies—those that owe their success to having a powerful set of capabilities that allow them to create unique value for customers—on average outperform their peers. In an age of rapid disruption, as the COVID-19 pandemic and rising environmental, social, and governance (ESG) expectations are quickly reshaping the context in which all businesses operate, putting capabilities at the heart of your strategy in general, and your M&A strategy specifically, plays an even more important role.

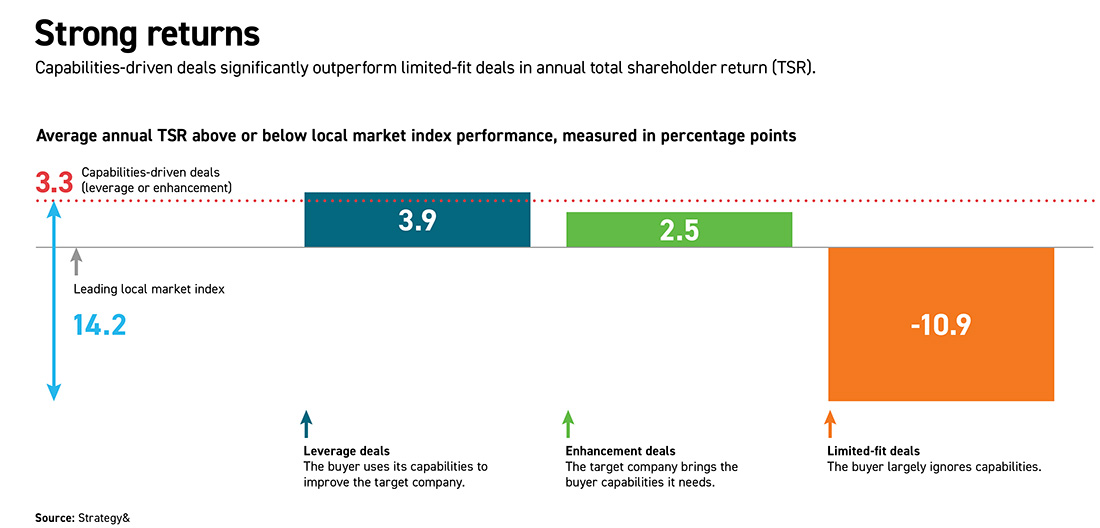

Over the past year, PwC examined 800 deals through a capabilities lens, including the 50 largest acquisitions in 16 different sectors completed in the past decade. Our examination was based on research conducted by Bayes Business School (formerly Cass Business School) that included the identification of acquisitions and the calculation of deal performance. We classified deals by whether they leveraged the buyer’s capabilities to generate more value from the target (leverage deals), used the target’s capabilities to enhance the buyer’s (enhancement deals), or largely ignored capabilities (limited-fit deals). We found that both enhancement and leverage deals generated a substantial premium in terms of annual total shareholder return (TSR)—2.5 and 3.9 percentage points above local market index performance, respectively—compared with an underperformance of 10.9 percentage points for limited-fit deals against the local market index (see chart).

These results tell us what happened in the past. But these same lessons apply to the rising number of deals struck in 2021—and beyond. The short-lived pandemic-induced slowdown in mid-2020 has given way to a surge of deals worldwide, as megadeals such as the AT&T–Discovery merger make global headlines (in this case generating an estimated US$130 billion in combined enterprise value). With deals running at record levels, powered by a combination of rising share prices, low interest rates, and the need for companies to adapt to a world of disruption, the stage is set for a sustained boom in M&A.

Understanding strategic intent and capabilities fit

Deals don’t always produce value. PwC research has shown that 53% of all acquisitions underperformed their industry peers in terms of TSR. And as PwC’s 2019 report “Creating value beyond the deal” shows, the deals that deliver value don’t happen by accident. Success often includes a strong strategic fit, coupled with a clear plan for how that value will be realized.

Armed with that knowledge, we set out to better understand the relationship between strategic fit and deal success. We first analyzed the deals’ stated strategic intent, as defined in corporate announcements and regulatory filings. Where several intents were present, we used the dominant intent. Then we classified each of the deals as one of the following:

• Capability access deals, for which the explicitly stated goal is to acquire some capability that the target has and the acquirer wants

• Product or category adjacency deals, in which a company buys a business with a product, service, or brand that is related to, but not identical to, its existing business categories

• Geographic adjacency deals, in which the acquirer uses M&A to expand into a new location

• Consolidation deals, which are intended to realize synergies and economies of scale, usually between two companies with similar businesses

• Diversification deals, which allow companies to enter a new or unrelated sector, typically with the rationale of insulating against the ups and downs of the business cycle.

We then assessed the capabilities fit between buyer and target for each of the 800 deals. As noted, we classified each deal as one of the following:

• Leverage deals, in which the acquirer buys a company that it knows or believes will be a good fit for its current capabilities system

• Enhancement deals, which are designed to bring the acquirer capabilities that it doesn’t yet have and that will allow it to intensify its own capabilities system

• Limited-fit deals, which occur when the acquirer largely ignores capabilities, meaning the transaction doesn’t improve upon or apply the acquiring company’s capabilities system in any major way.

To measure deal success, we determined the buyer’s annualized TSR over a period ranging from just before the deal’s announcement to one year post-closing and compared the TSR with the performance of the leading local market index over the same period. We were then ready to determine the correlation between strategic fit—either stated strategic intent or capabilities fit—and deal success.

Quantifying the capabilities premium

The findings underline that the capabilities premium for both leverage and enhancement deals is a powerful expression of value creation. Leverage deals, in which the buyer uses its capabilities to strengthen the target, performed slightly better on average than enhancement deals, in which on-boarding new capabilities often comes with greater complexity.

SS&C Technologies’ 2018 acquisition of DST Systems offers a perspective on doing a leverage deal in which a global company acquires a complementary provider of software and technology in the financial-services and healthcare sectors. The $5 billion deal enabled SS&C to both expand its footprint into the US retirement and wealth management industry and leverage its software platform to increase the efficiency and digital capabilities of asset managers.

For an example of an enhancement deal, consider Amazon’s $13.6 billion acquisition of Whole Foods in 2017. The deal gave Amazon the capability to sell in physical outposts, which it used to drive the expansion of its Amazon Fresh stores. Moreover, the deal provided the retail giant with a new knowledge base in the grocery industry, setting the stage for Amazon to disrupt the category by moving it online.

Limited-fit deals, which had a negative TSR compared with the local market indexes (–10.9 percentage points), typically destroyed value compared with the market. For every dollar spent on M&A, roughly 25 cents were spent on such limited-fit deals. Accounting for the 800 deals considered, this added up to more than $900 billion in transaction value spent on deals lacking a capabilities fit.

For every dollar spent on M&A, roughly 25 cents were spent on limited-fit deals. Over 800 deals, this added up to more than $900 billion in transaction value spent on deals lacking a capabilities fit.

When we analyzed deal success versus stated strategic fit, we found that the stated strategic intent had little or no impact on value creation, with the logical exception of capability access deals. Whether a deal fits depends minimally on its aim. What matters is whether there is a capabilities fit between the buyer and the target.

Indeed, there was little variance among the remaining four types of deals—product or category adjacency, geographic adjacency, consolidation, and diversification—which on average performed either neutrally or negatively from a value-generation perspective compared with the market. Geographic adjacency deals stood out as performing less well than others, largely because many of them (34%) were limited-fit deals. This seems to indicate that buyers had underestimated what it would take to succeed outside their existing geographic footprint and overestimated how far their capabilities could travel.

At an industry level, there is a high degree of variability in frequency of capabilities-driven deals and size of the capabilities premium. Even so, a positive capabilities premium was evident in each of the 16 industries analyzed, even in those, such as oil and gas (38% of those deals were capabilities-driven), in which asset acquisition can play a significant role in addition to capabilities fit.

How to maximize value from deals

Amid the current market turbulence, competitors are racing to capitalize on the window of opportunity presented by the post-COVID-19 recovery. Companies must be very clear about which capabilities they can leverage to succeed and which gaps in their capabilities they need to fill. But as the importance of focusing on capabilities intensifies, the need to move quickly also increases the pressure to pursue M&A deals at pace—and thereby increases the risk of failing to evaluate capabilities fit with enough care. We think this is a pitfall acquirers should actively seek to avoid.

The first step is to understand how the M&A playing field has changed. COVID-19 has triggered five main shifts in the global business environment. It has:

• Accelerated the already rapid pace of digitization

• Increased the importance of sustainability

• Intensified growth opportunities and the need for agility in business models

• Heightened the focus on having resilient, adaptable supply chains

• Hastened the ongoing transformation of the workforce—including more remote working.

Given the importance of adapting quickly to the changed environment, organic change is often simply too slow. As a result, the traditional options of “build, buy, or borrow” have tipped sharply toward “buying,” which is fueling M&A activity, and “borrowing,” wherein companies seek to share capabilities within ecosystems. Underlying all this is a powerful impulse to forge new equations for creating value for customers and society. The key is to understand and pursue the actions that will ensure a successful deal. Consider these five steps:

Determine the capabilities you have and the ones you need. Given your strategy and the way in which you aim to add value for your customers, which capabilities do you need to excel at in order to succeed now and in the future? Where do you have gaps you need to fill? To help answer these questions, you may consider running the Capabilities Assessment Tool from Strategy&, PwC’s strategy consulting business; the tool is designed to enable an organization to identify the capabilities it has and understand which ones it will need to thrive. Then you will need to assess what is the best way to fill your capabilities gap—should you build those capabilities organically, or should you acquire or partner with a company that has what you need?

Conduct ongoing portfolio optimization reviews. Revisit and reexamine your portfolio through a capabilities lens. Are your businesses coherent, i.e., do they leverage a common set of differentiating capabilities? Are there businesses that you should divest because you don’t have the capabilities that give you a right to win? Which businesses should you seek to acquire because your strengths would boost them into a whole new league?

Become a prepared, always-ready acquirer. Combine and build on the insights from the first two steps to turn M&A effectiveness into a differentiating capability in its own right for the firm. Have you assessed the universe of potential acquisitions from a capabilities perspective? Do you know which assets in your industry may be a better fit with your capabilities system than with their current owner’s, or are you overly reliant on advice from investment bankers to identify targets?

Build distinctive M&A integration (MAI) insight and capability. As underlined by PwC’s 2020 M&A Integration Study, MAI is absolutely critical in delivering value from any deal, but needs to be tailored to each deal’s unique attributes and characteristics. Are you integrating a target that will help you enhance capabilities? Or are you integrating a target to leverage your capabilities? In the first case, you need to scrutinize the building blocks of the capability you are acquiring to carefully connect it with your own strengths. In the second case, you have the opportunity to be more aggressive, and to use your capabilities to improve the target. In each instance, a thorough understanding of integration strategy and tactical execution is essential to achieving your deal’s true potential.

Be decisive and act now. If an acquisition or division doesn’t fit from a capabilities lens, protect value and management bandwidth by exiting it quickly, rather than trying to turn it around. Likewise, if there is a gap in capabilities, you need to act now to fill it, or you will be left behind in the race to win.

Taking these five steps can help ensure a strategic fit that’s aligned with your capabilities, dramatically increasing your chances of creating value. And the time to embark on these steps? Today. Because doing the wrong M&A deal is simply not an option.

Research methodology

In our study, we examined the 50 biggest acquisitions globally by transaction value completed between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2018, in each of 16 industries: automotive; banking, capital markets and asset and wealth management; chemicals; consumer goods; entertainment and media; health services; industrials; insurance; metals and mining; oil and gas; pharma and life sciences; power and utilities; retail; technology; telecommunications; and transportation and logistics. In selecting deals for analysis, we excluded those made by buyers that were not listed on a public stock exchange throughout the one-year post-deal performance measurement period (described in more detail below). We also excluded transactions in which the buyer was involved in another major deal during the performance measurement period, as this may have blurred the impact of the initial deal. The biggest transaction captured by our filter was Anheuser-Busch InBev’s US$101.5 billion purchase of SABMiller in 2016; the smallest was a $95 million acquisition in the automotive sector in 2017.

To measure the performance of the 800 deals in our research sample, we calculated the acquirer’s annualized total shareholder return (TSR)—stock price plus dividends—in the period running from one month before the announcement of the acquisition to 12 months after it closed. This is the time window referred to as the “performance measurement period” in the paragraph above: we limited it to one year because the longer the time frame, the more “noise” there will be, and the less attributable share price differences become to the deal itself. We then compared each deal’s performance with the compound annual TSR growth rate of the large-cap index in the acquiring company’s home country over the same time frame. The indexes we used as benchmarks included the CAC 40 in France, the DAX in Germany, the FTSE 100 in the UK, the S&P 500 in the US, and the KOSPI Index in Asia. If the company did not pay any dividends during the period, the TSR was equivalent to the rise (or fall) in the company’s share price.

There was one aspect of the research that required a degree of judgment: the classification of the intent of each deal, and especially the targeted fit from a capabilities perspective. To help us reach a robust view on this, we drew on corporate announcements, external press coverage, and SEC filings. In classifying the deals in terms of capabilities fit, we ultimately relied on our judgment, our analysis, and our experience with the companies involved, which enabled us to determine whether each deal was fundamentally enhanced, leveraged, or largely ignored the acquirer’s capabilities.

Inevitably, we found that some deals appeared to have multiple goals—such as aiming both to leverage and also to enhance capabilities. In these cases, we allocated the deal to the single category in which we believed it had the best fit.

Author profiles:

- Alastair Rimmer leads PwC’s deal strategy practice globally at Strategy&, PwC’s strategy consulting business. He has more than 30 years of strategy and transactions experience, and during his consulting career, he has worked extensively across the US, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. He is a partner with PwC UK.

- Hein Marais is PwC’s global value creation leader and head of UK transaction services. His career in the deals market spans more than 25 years. A partner with PwC UK, he focuses on transactions that involve complex global divestitures and integrations.

- Gregg Nahass has completed more than 300 transactions in his 30-year career and is a leader in M&A integration services globally for PwC. He is an adjunct professor at the University of Southern California in the Marshall School of Business and a partner at PwC US.

- Also contributing were PwC US partner John D. Potter, PwC UK partner Will Jackson-Moore, PwC Germany partner Peter Gassmann, PwC Switzerland director Nadia Kubis, and PwC Spain partner Malcolm Lloyd.