Succeeding the long-serving legend in the corner office

According to the 19th annual CEO Success study by PwC’s Strategy&, boards and new CEOs can reduce the risk associated with handing off the baton after a long tenure.

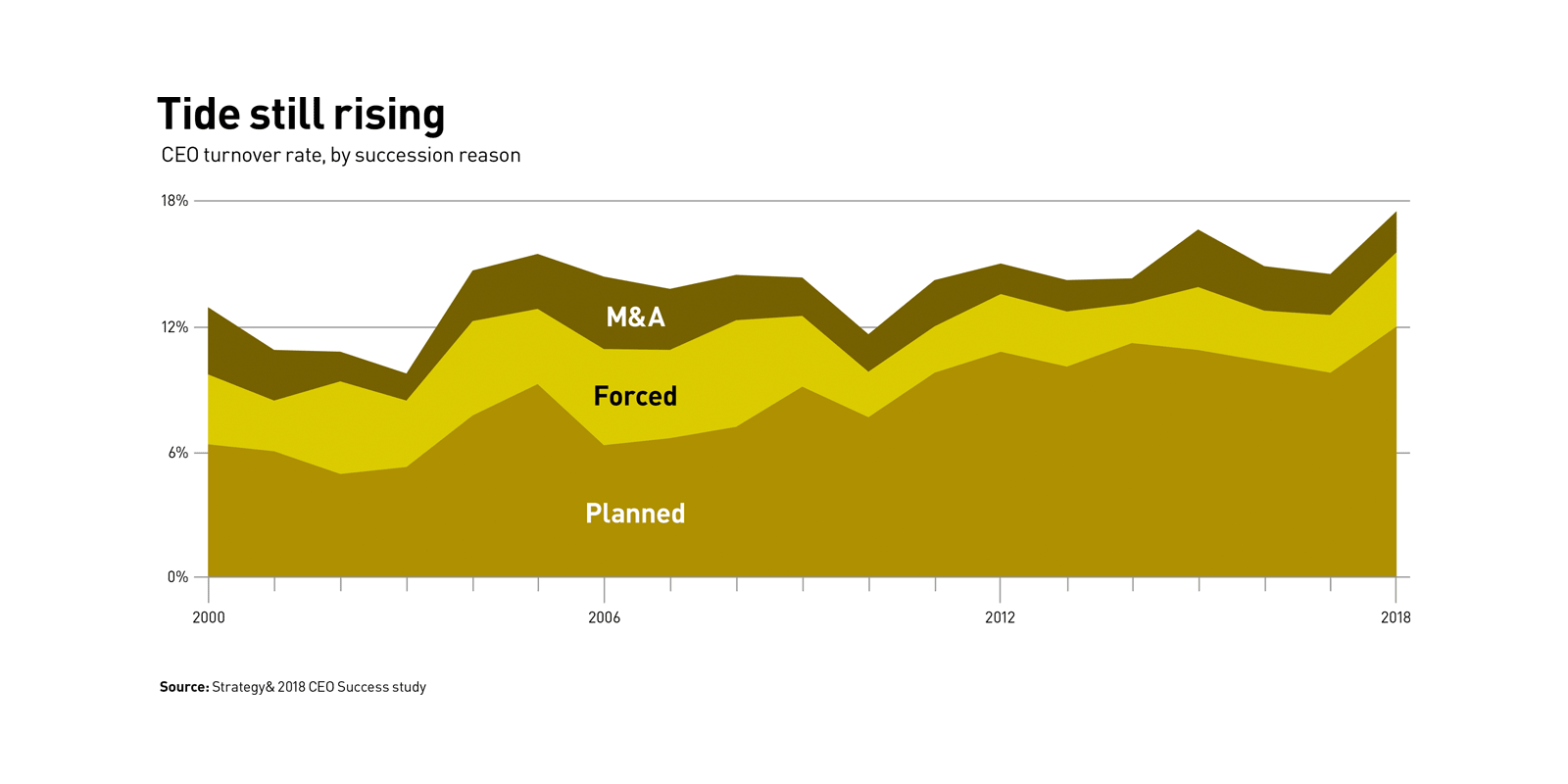

It’s no secret that life at the top of the corporate world is becoming more challenging. Last year, nearly 17.5 percent of the CEOs of the world’s largest 2,500 companies left their posts — representing the highest rate of departures that PwC’s Strategy& CEO Success study has tallied in its existence. In 2000, a CEO could expect to remain in office for eight or more years, on average. Over the last decade, however, average CEO tenure has been only five years.

And yet a substantial subset of CEOs manages to run the equivalent of a corporate marathon, lasting nearly three times as long as the average boss. Even as the life of CEO becomes nasty, brutish, and short, 19 percent of all CEOs manage to remain at the top for 10 or more years, with a median tenure of 14 years. Some of these long-distance runners, typically company founders or visionaries who transformed their organizations, serve for 20 years, and in some cases for many years longer. All of them have had impressive runs atop their company and created a legacy.

But what happens when the baton is passed to the next runner? Sometimes things go great when a long-serving CEO departs. When Apple’s legendary founder Steve Jobs stepped down eight years ago for health reasons and Tim Cook ascended to the top job, it was hard to see how he could fill Jobs’s colossal shoes — even though Cook had been an effective chief operating officer and was the clear heir apparent. But Cook has done well: Annualized total shareholder returns since he took over in August 2011 averaged an impressive 20.9 percent through 2018.

Sometimes, however, the transition winds up in disaster. When Jeffrey Immelt departed after a 17-year tenure atop General Electric in 2017, his successor, longtime GE executive John Flannery, launched a major transformation to turn around the troubled conglomerate. The plan quickly went awry amid disappointing financial results and negative disclosures; 14 months into Flannery’s tenure, he was dismissed by the board and replaced by Larry Culp, the former chief executive of Danaher and the first outsider recruited as CEO in GE’s 126-year history.

To be sure, most departures of long-serving chief executive officers are less dramatic or fraught. The vast majority of long-serving CEOs leave office in a planned succession and are followed by a company insider. Most transitions go smoothly, as was the case at Starbucks, where founder and long-term CEO Howard Schultz was succeeded in 2017 by Kevin Johnson, the former president and chief operating officer, or at Vanguard, where Bill McNabb resigned in 2018 after 10 years at the top and was succeeded by chief investment officer Tim Buckley. In other cases, the transition signals a change in direction: At Daimler, for example, Dieter Zetsche departed two years ahead of schedule in 2018 after a 13-year run as head of the automaker. He was succeeded by Ola Källenius, the head of R&D, whose background is in innovation, mobility, and digital change.

The experiences surrounding long-serving CEOs were a focus of this year’s CEO Success study by Strategy&, PwC’s strategy consulting business, which examined all turnovers of chief executives at the world’s 2,500 largest publicly traded companies from 2004 to 2018. When we isolated the data from 2018 successions, we found it was a turbulent year, as the percentage of CEO turnovers rose to a record high (see “CEO turnover in 2018”).

CEO turnover in 2018

Turnover among CEOs at the world’s 2,500 largest companies soared to a record high of 17.5 percent in 2018 — 3 percentage points higher than the 14.5 percent rate in 2017 and above what has been the norm for the last decade. Percentages of the types of turnovers — planned, forced, and M&A-related — remained in line with long-term trends. Planned successions continued to account for more than two-thirds of all turnovers (see “Tide still rising”).

The overall rate of forced turnovers was in line with recent trends, at 20 percent. But the reasons that CEOs were fired in 2018 were different. For the first time in the study’s history, more CEOs were dismissed for ethical lapses than for financial performance or board struggles. (We define dismissals for ethical lapses as the removal of the CEO as the result of a scandal or improper conduct by the CEO or other employees; examples include fraud, bribery, insider trading, environmental disasters, inflated resumes, and sexual indiscretions.) The rise in these kinds of dismissals reflects several societal and governance trends, including more aggressive intervention by regulatory and law enforcement authorities, new pressures for accountability about sexual harassment and sexual assault brought about by the rise of the “Me Too” movement, and the increasing propensity of boards of directors to adopt a zero-tolerance stance toward executive misconduct. (For background on this trend, see “Are CEOs Less Ethical Than in the Past?” s+b, May 15, 2017.) The growing presence and power of activist investors could also be a contributing factor to the higher rate of CEO turnover.

Regions, industries, and demographics

CEO turnover rose notably in every region in 2018 except China, and included a large increase in Western Europe. Turnover was highest in “other mature” economies (such as Australia, Chile, and Poland), at 21.9 percent, and nearly as high in Brazil, Russia, and India (21.6 percent). The next-highest turnover numbers were in Western Europe (19.8 percent), and the lowest were in North America (14.7 percent).

Among industries, turnover was highest in communication services companies (24.5 percent), followed by materials (22.3 percent) and energy (19.7 percent). Healthcare saw the lowest rate of CEO turnover in 2018, at 11.6 percent.

The share of incoming outsider CEOs in 2018 was the lowest since 2007, at 17 percent. For the first time in six years, insiders outperformed outsiders. Among CEOs who left office in 2018, insider CEOs’ median annualized total shareholder returns were 0.8 percentage points higher than those of outsiders. This outperformance, which we discuss in the main article, is reminiscent of the period between 2000 and 2012, when insiders had higher returns than outsiders in 10 out of 13 years.

The global median tenure for all CEOs has remained steady at five years for the last decade, and the 53-year median age of incoming CEOs has also been steady over the last decade. The share of incoming CEOs with previous experience as CEO of a public company has been increasing for the past several years, particularly in Western Europe, where 39 percent of incoming CEOs in 2018 had previous CEO experience.

Women CEOs

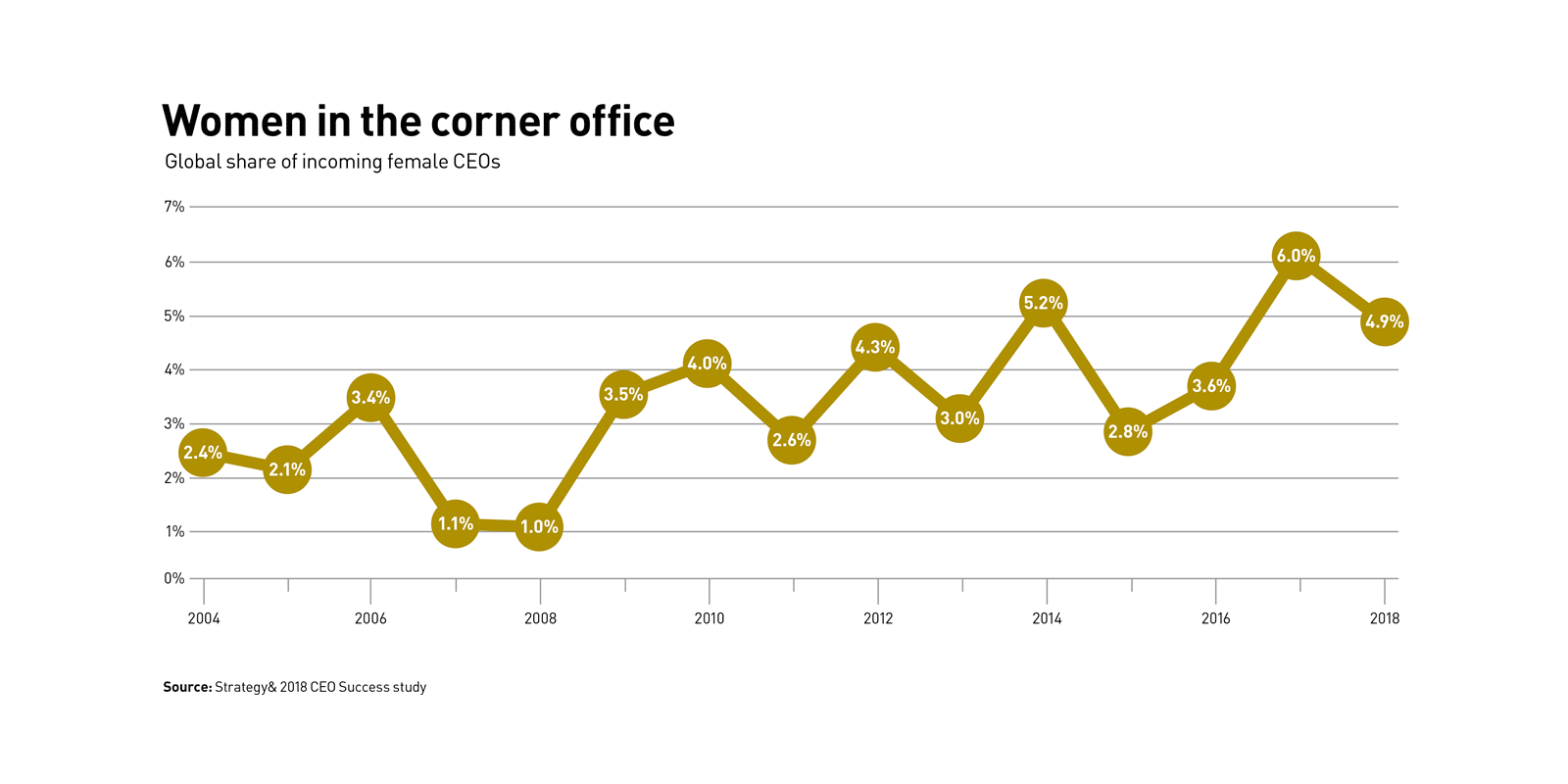

The share of incoming women CEOs was 4.9 percent in 2018. This is down slightly from the all-time high of 6 percent in 2017, but it continues an upward trend from the low point of 1 percent in 2008 (see “Women in the corner office”). Unlike in 2017, when the record high was driven by a 9.1 percent spike in incoming women CEOs in the U.S. and Canada, the largest share of women CEOs in 2018 resulted from sharp increases in Brazil, Russia, India, China, and “other emerging” countries. Among industries, utilities had the largest share of incoming women CEOs (9.5 percent), followed by communications services (7.5 percent) and financials (7.4 percent). The lowest share? No women became CEOs of industrials or information technology companies in 2018.

As one would expect, long-serving CEOs generally deliver higher shareholder returns than shorter-serving CEOs, though their performance, on average, tends to be good rather than great. They typically play a key role in arranging a smooth succession to a carefully chosen insider executive at their company. CEOs at North American companies are much more likely to be long-serving than those in other regions, and they are also much more likely to hold the joint titles of CEO and board chair at the time of their departure. Overall, this trend toward outgoing CEOs holding joint titles in North America has been rising, from 31 percent in 2014 to 48 percent in 2018, compared with an average of 23 percent for other regions. The trend is even more pronounced for long-serving CEOs.

Successors to long-serving CEOs, however, face a difficult path. Following a legend is not for the faint of heart. Although they often have much in common with their predecessors in terms of their backgrounds, successors turn in significantly worse financial performance, generally have shorter tenures, and are much more likely to be forced out rather than to depart via a planned succession.

In this year’s CEO Success study, we zero in on the seemingly anomalous phenomenon of the long-serving CEO in this tumultuous age, delving into the characteristics that set these leaders apart and analyzing how they transition. We also examine the characteristics of the successors to these long-serving CEOs, focusing particularly on the smaller universe of successors who have completed their terms as CEO during the 15-year period we studied, and the reasons that they struggle to meet or beat the performance of their predecessors and, in fact, all other CEOs.

We also consider the questions that the boards of directors at companies with long-serving CEOs should be asking themselves: Given the long odds that successors face, how can the board best provide support? Is there a case to be made for boards to be more open to hiring outsiders to replace a legendary CEO, despite a decades-long trend favoring insider candidates? Last, we provide some tips to executives who are in line, or under consideration, to succeed a long-serving CEO for how they can step out of the shadow of a legend and defy the odds to produce a successful succession.

Settling in to the C-suite

We reviewed all successions at the world’s 2,500 largest listed companies from 2004 to 2018 — a total of 5,253 turnovers — and identified all departing CEOs who had served for more than 10 years as CEO. Nearly a fifth of all the departing CEOs over the 15 years of data — 994 — had achieved this milestone. The percentage of long-serving CEOs each year has, in fact, held steady. Long-serving CEOs were more likely to be insiders (84 percent) than were shorter-serving CEOs (77 percent), a situation that was especially true in the last three years. In 2018, 90 percent of all departing long-serving CEOs had been insiders when they were promoted to their post.

Long-serving CEOs are most common at North American companies by a significant margin. Over the full period, 30 percent of the CEOs in North America were long-serving, compared with 19 percent for Europe, 10 percent for the BRI countries (Brazil, Russia, and India), 9 percent for Japan, and only 7 percent in China. In fact, over the last 15 years, CEOs in North America were 122 percent more likely to be long-serving than CEOs in the rest of the world.

Several factors may explain these regional differences. Typically, long-serving CEOs earn their tenure — that is to say, those who stay in their positions for long periods do so because their companies are performing well and thus are given a certain amount of deference by their boards. But in Japan, where societal norms favor earlier retirement than is the case in most other countries, CEOs typically assume office later in their career and serve for only a few years, moving on to become the board chair as a younger executive succeeds them. In China, where the corporate governance model is of more recent vintage, the government sometimes shuffles CEOs within or between industries, and there is generally more change in industries than is true in more mature regions, with some companies rising or failing fast or being sold as the markets and the regulatory environment change.

Among industries, CEOs in healthcare were the most likely to be long-serving (28 percent probability), followed by those in information technology (26 percent). We found few other proportionality differences among long-serving CEOs by industry.

The median tenure of a long-serving CEO is 13.9 years, compared with 4.0 years for other CEOs — more than three times as long. One likely reason for these longer tenures is that 46 percent of long-serving CEOs hold joint CEO and board chair titles by the time they depart, a number that is more than twice as high as the 21 percent share for shorter-serving CEOs. This finding again reflects the overrepresentation of long-serving CEOs in the U.S., where the joint titles have remained far more common than in other regions. As many as 67 percent of long-serving CEOs in North America depart with the joint title. By the time of their departure, long-serving CEOs obviously know their board members well, and have likely influenced the selection of many or most of them.

But the main reason for the long tenure of these CEOs is that they generally outperform their shorter-serving peers. The median regionally adjusted annual increases in total shareholder return (TSR) for long-serving CEOs was 5.7 percent over the 2004–18 period — 3.3 percentage points higher than for other CEOs. Moreover, 59 percent of the long-serving CEOs were in the two upper quartiles of TSR performance, compared with only 47 percent of non-long-serving CEOs. And only 8 percent of the long-serving CEOs were in the bottom performance quartile, compared with 28 percent for shorter-serving CEOs. Over the last three years, the performance of long-serving CEOs has improved even more, with 64 percent in the top two quartiles, and a mere 7 percent in the bottom quartile. This suggests that boards of directors have gotten stricter about allowing CEOs to continue long tenures unless the performance is notably positive.

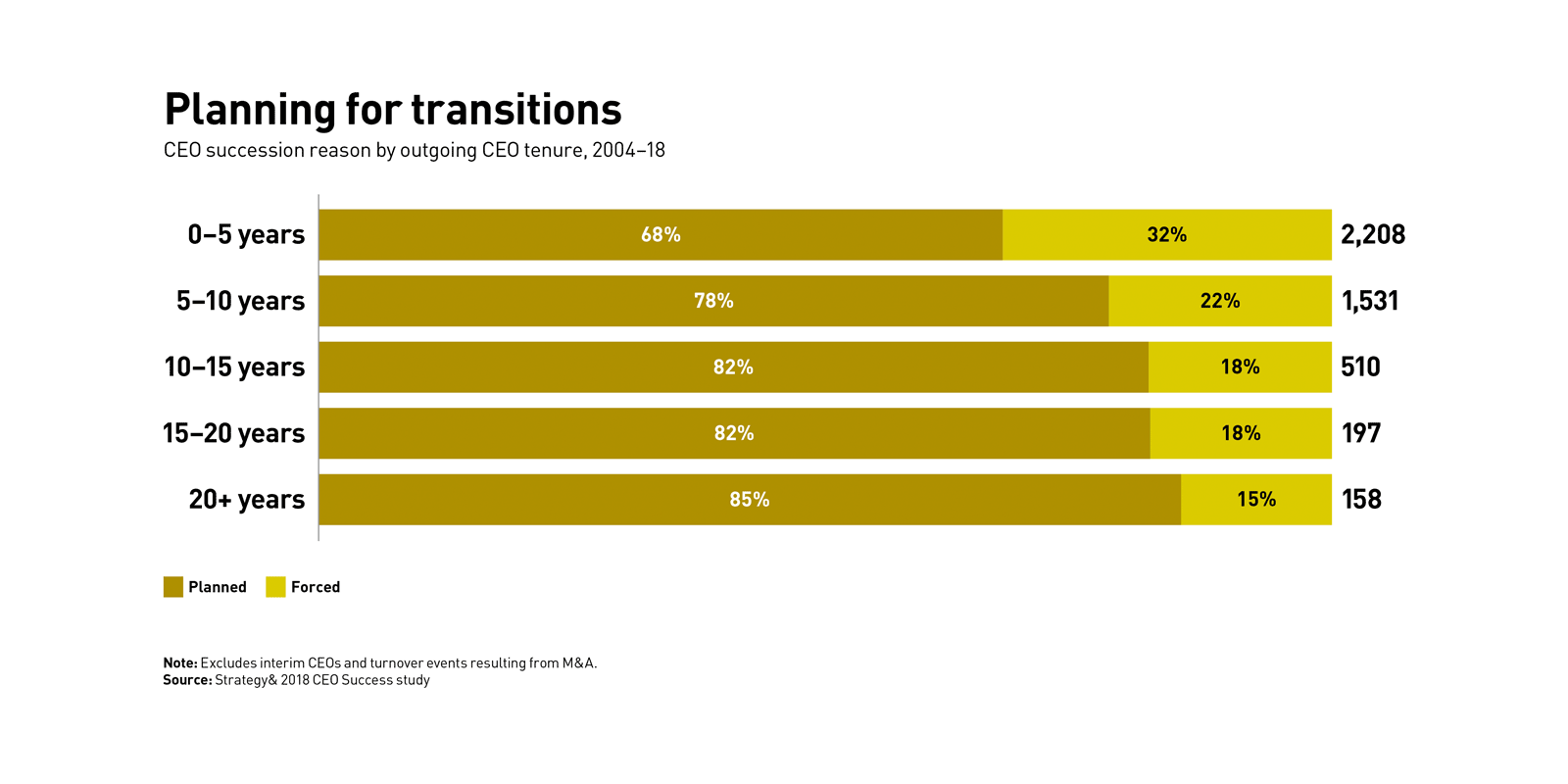

The great majority of departures of long-serving CEOs are carefully planned and executed, in line with a decades-long global trend toward planned successions. And there’s good reason for making such plans. Our research in previous CEO Success studies has shown that planned successions are associated with higher TSRs (see “The $112 Billion CEO Succession Problem,” s+b, May 4, 2015). From 2004 to 2018, 82 percent of long-serving CEOs left office in a planned succession. Over the last three years, the number has risen to 85 percent, compared with 76 percent for other CEOs. The number of departures resulting from an M&A transaction is almost the same for long-serving CEOs and other CEOs.

We also found that the longer a CEO is in office, the less likely he or she is to be forced out (see “Planning for transitions”). Thirty-two percent of CEOs who depart in the first five years of their tenure are fired. But that proportion falls to 22 percent for those who leave after serving between five and 10 years, 18 percent for those who leave after serving between 10 and 20 years, and just 15 percent for those who make it past their 20th anniversary. This trend obviously reflects the fact that long-serving CEOs are performing better than other CEOs, and it may also be due in part to the fact that a much larger percentage of long-serving CEOs hold joint CEO–board chair titles. (It should be noted that most of the CEOs who acquire the chairman title do so during the course of their tenure, not at the outset.)

Long-serving CEOs were also more likely to remain as board chair after stepping down from the chief executive role in a planned succession. Over the last three years, 48 percent of long-serving CEOs either remained as board chair or assumed the role at the time of the succession, compared with 28 percent for shorter-serving CEOs.

The successor CEO’s tough road

The challenge faced by successors of long-serving CEOs comes into sharp focus when we zoom in on the smaller number of companies at which, between 2004 and 2018, a long-serving CEO departed and his or her successor also finished his or her tenure. We excluded interim CEOs and transitions that resulted from M&A from this group because such events are often unique, and the performance following the transaction is driven by many factors, not least the economics involved in the transaction itself. This leaves a subset of 284 companies among which we can make a direct comparison between the performance of the long-serving CEO and his or her successor over their full respective tenures. One reason for the small size of this data set, naturally, is that some long-serving CEOs have left their position only recently, and their successor is still in place.

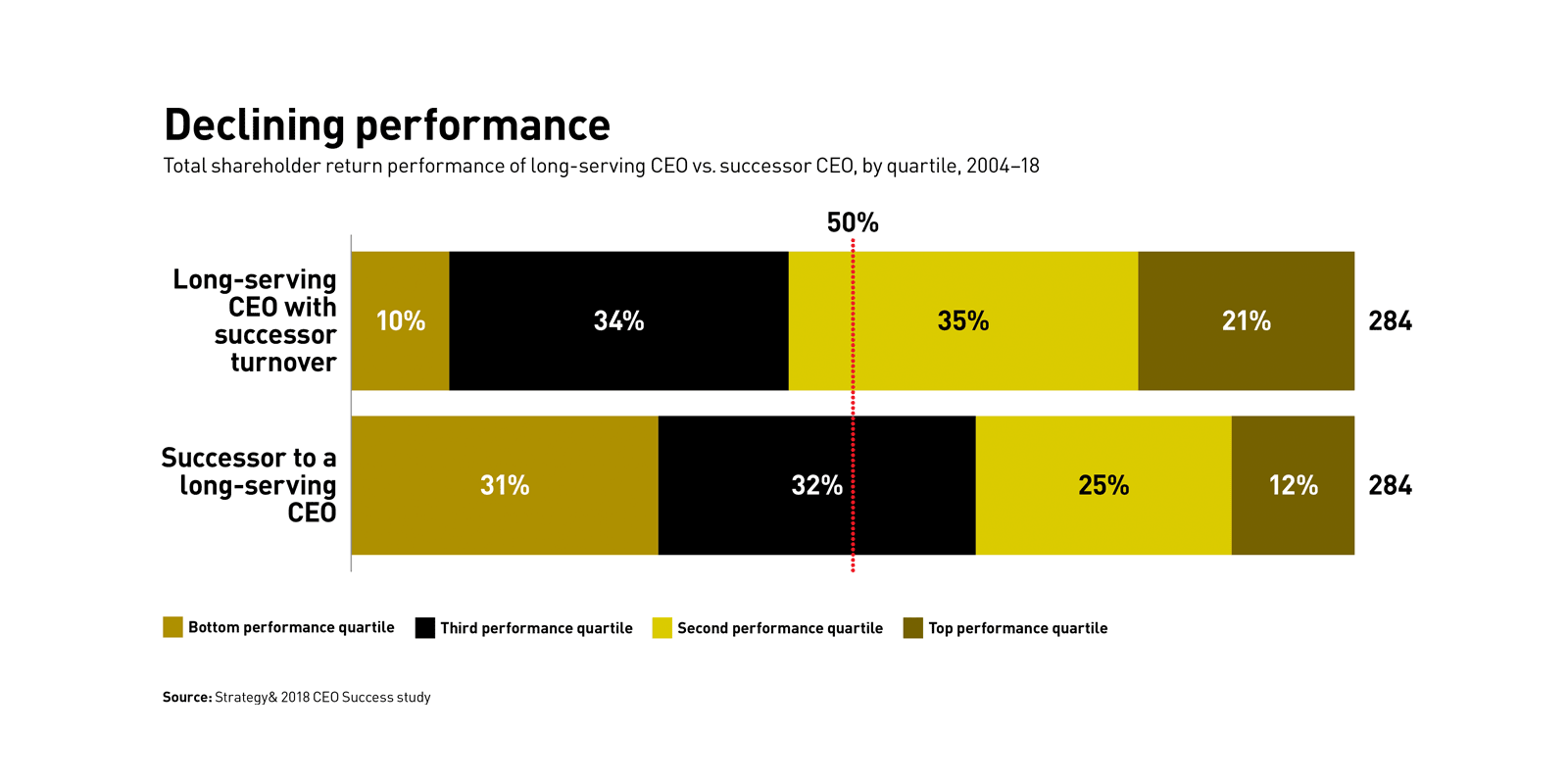

Among this subset of companies, the median successor’s annualized TSR was a sobering 4.0 percentage points lower than that of the replaced long-serving CEO. Comparing the performance of the two groups of CEOs by looking at the TSR performance quartile in which they fall provides further insights. The long-serving CEOs largely performed better (56 percent were in the top two quartiles) than their successors (only 37 percent of whom were in the top two quartiles). Worse, 31 percent of the successors were in the bottom TSR quartile, compared with only 10 percent of their long-serving predecessors (see “Declining performance”).

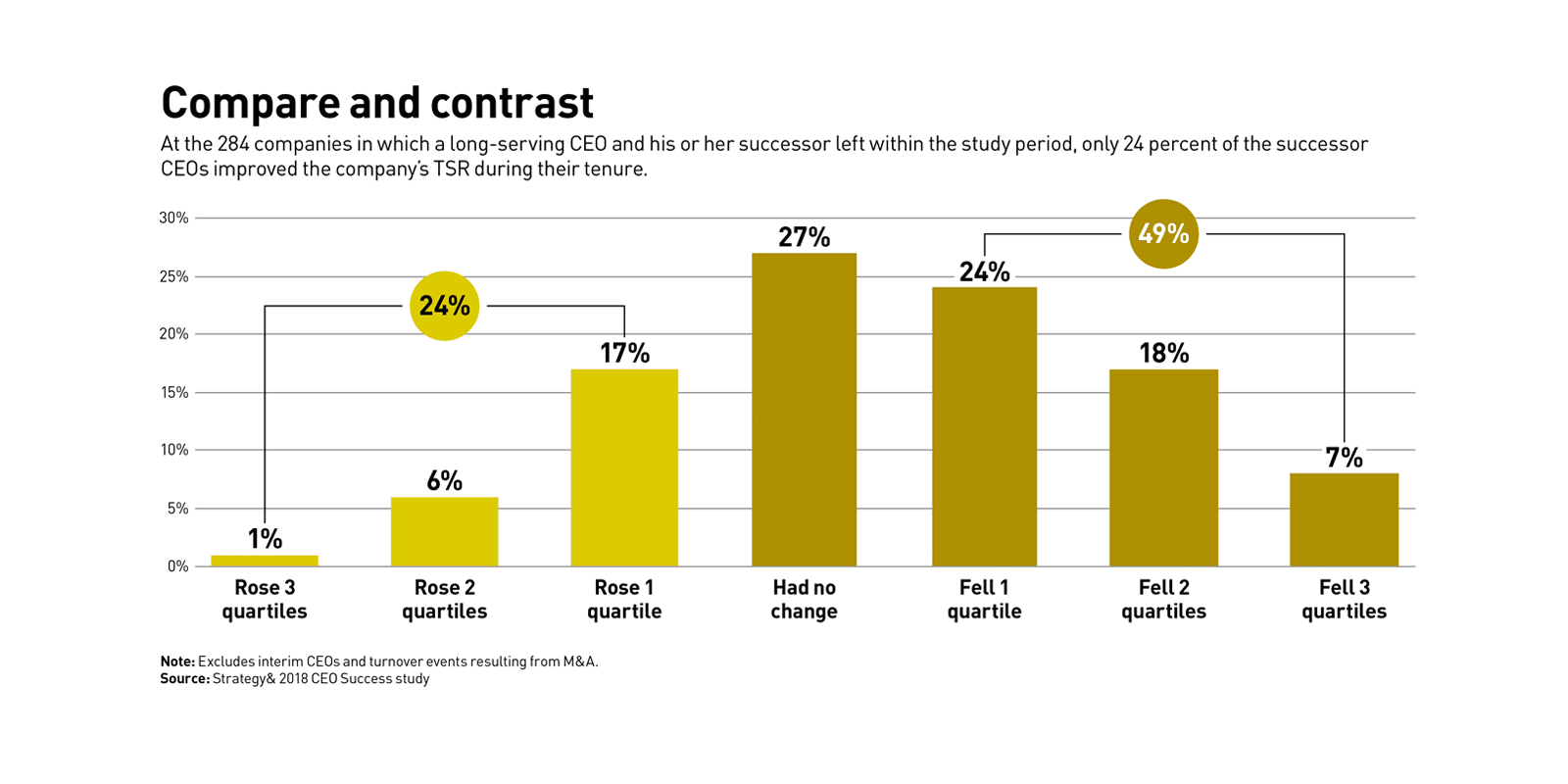

Close to half of the successors who replaced long-serving CEOs moved the company’s TSR down by one or more quartiles (see “Compare and contrast”). Only 24 percent moved it up to a higher quartile, and 27 percent saw the TSR hold steady. The performance change pre- and post-succession was even more pronounced when the long-serving CEO was a top performer. In cases in which the outgoing CEO was in the top performance quartile, 69 percent of the successors ended up in the bottom two TSR quartiles.

Moreover, the longer the long-serving CEO’s tenure, the worse the successor performed. Among successors who replaced a CEO with a tenure of 10 to 15 years, 42 percent had a TSR in the top two quartiles, compared with 35 percent for those following a CEO with a 15- to 20-year tenure, and 25 percent for those following a CEO with a tenure of 20 or more years.

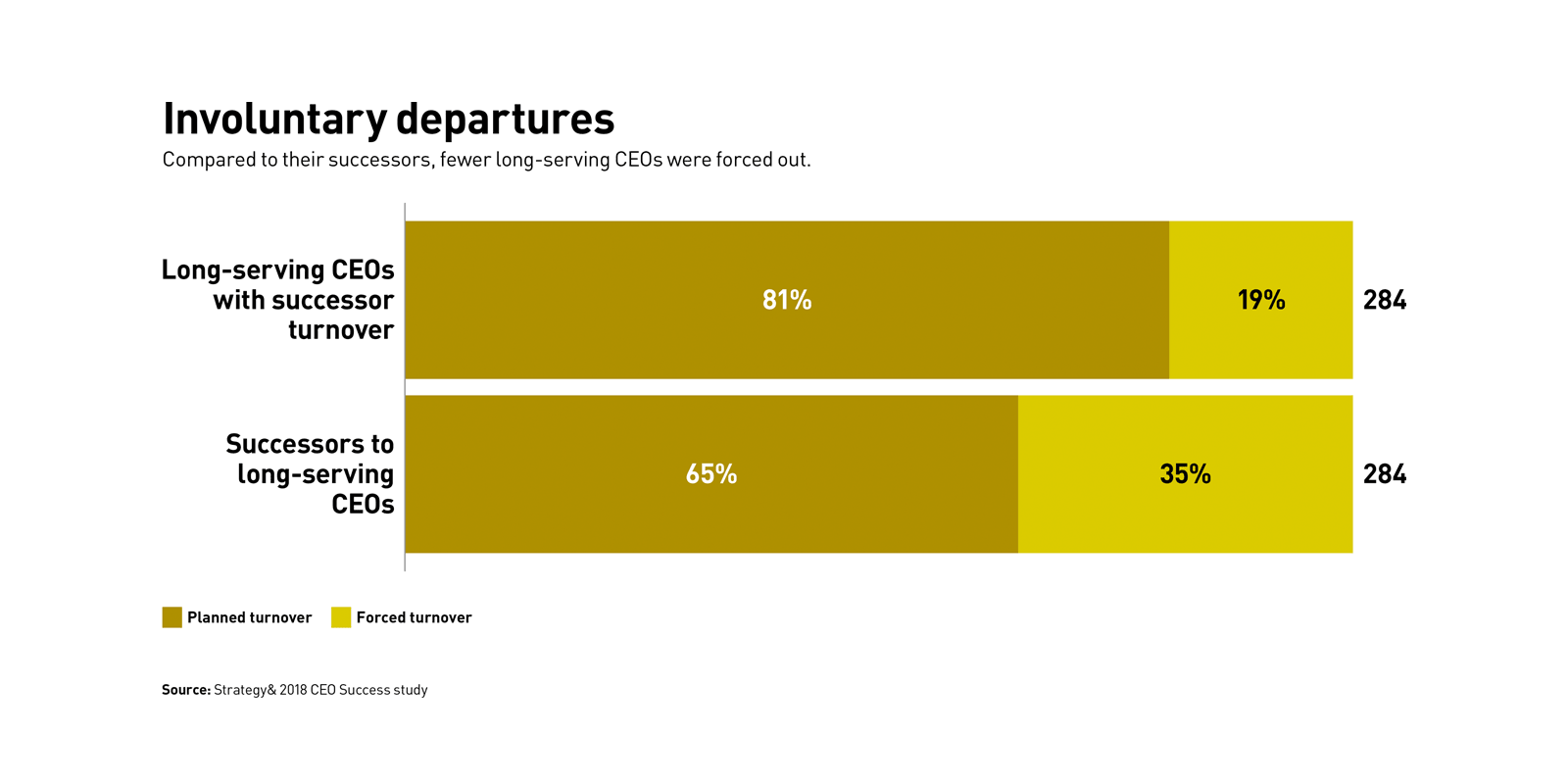

Not surprisingly, the median tenure of the successors to long-serving CEOs is far shorter than those of the leaders they replace (5.3 years versus 13.7 years), and they are significantly more likely to be forced out than their predecessor (35 percent versus 19 percent; see “Involuntary departures”).

The data doesn’t tell us why it is so difficult to take over from a long-serving CEO. But we have some hypotheses, based on our own experience advising and observing leadership teams and boards of directors. In some cases, the long-term CEO simply doesn’t set up his or her successor to succeed. Above-average TSR data, for example, may mask a lack of midterm and long-term investments that the company needs to make to enable future success. Other leaders and board members — and investors — are less inclined to rock the boat if it is helmed by a long-serving, generally successful CEO than they might be in other circumstances. The problems then become evident only after the successor takes over.

Implications for boards and successors

For board members, oversight of a long-serving CEO can be tricky. On the one hand, it’s difficult to make a change when the CEO has performed well over a long period, and there’s much to be said for continuity and predictability. On the other hand, virtually everyone grows stale at some point, and can easily become locked into a certain frame of mind. Given the rapid pace of change inspired by digital technologies, long-serving CEOs are likely dealing with a context that is significantly different from the one they are accustomed to. In addition, some of the best possible successors within the senior executive ranks may not be willing to hang around indefinitely. They may themselves become impatient and leave, or be poached by another company.

The longer the long-serving CEO’s tenure, the worse the successor performed.

Board members should think carefully about the right time to shift from a long-serving CEO to a new candidate — especially in cases in which the incumbent CEO’s performance is average, or even good but not great. New blood brings energy and perhaps a new perspective on how to drive the business. Boards of North American companies should be especially wary. The strong overrepresentation of long-serving CEOs suggests that succession decisions may be delayed in North America compared with the rest of the world, increasing the risk of a failed succession. Our data, as noted earlier, shows that it is much harder for the successor to flourish following a long-serving predecessor, and the longer the predecessor’s tenure, the more challenging it is for the successor to perform. Boards have to take care not to become complacent. Term limits, mandatory retirement ages, or other mechanisms aimed at limiting CEO tenure are not a panacea. Boards have to continuously evaluate whether the person sitting in the company’s top slot is up to the task as conditions change.

Boards need to acknowledge that statistically speaking, successors to long-serving CEOs start with the deck stacked against them. As a result, the board needs to make clear that the new CEO has their support, and that they are not constraining the successor as he or she is thinking through a plan for the company’s future. This issue can be particularly dicey when the outgoing CEO is also the board chair: The rest of the board should be wary of the chair continuing to run the company and impeding the successor.

Boards should be generally mindful of the merits of separating the roles of chief executive and board chair. Although we lack evidence that one performs better than the other on average, many governance experts agree that separate roles are the best practice, and governance standards have moved in that direction in many regions. We do know that combining the roles increases the risk of ethical lapses. In our 2017 study, we found that among CEOs who were forced out, 24 percent of those with joint titles were dismissed for ethical lapses, compared with 17 percent of those with the CEO title only.

Boards should also consider whether the best candidate to succeed a long-serving CEO may be an outsider rather than an insider. In five of the last six years, when we examined the performance of departing CEOs, those who had come in as outsiders outperformed insiders. One hypothesis for this differential is that in the current climate of disruption, technological advances, and changing competitive dynamics, the most effective candidates may be those whose backgrounds, perspectives, and skill sets are different from those possessed by the in-house candidates.

For executives who may be in line to succeed a long-serving CEO, all the standard advice for new CEOs applies. Calling upon our experience in the trenches with top management across a variety of sectors, and our previous annual surveys exploring CEO Success, we’ve identified several game-changing practices that will substantially contribute to success for new CEOs. They are especially useful for those who fit the typical profile of the successor to a long-serving CEO — namely, an executive who came up from inside who has deep knowledge of the company but no prior CEO experience, who does not hold the concurrent position of board chair, who has no COO, and who faces high board expectations.

If you are a potential successor, you should:

1. Build your own brand. You can never truly replace a charismatic or legendary leader, so don’t try to emulate the outgoing CEO’s style. If you’re an insider, you already know everyone and everything in the company, and likely have filled many different roles. But you need to change on multiple dimensions to evolve from the past roles into your new leadership position. You should spend time with external stakeholders building credibility. In planned successions, much can be done following the announcement of impending change — so use this time wisely.

2. Set the agenda. Your predecessor is likely a dominant figure, and one of your key tasks as the new CEO will be to establish a new agenda and reshape the future. This should start with a thorough review of all operations and strategy. And it can continue by breaking the frame (for example, by changing some fundamental aspect of the company’s business model), resetting expectations, and integrating the company parts with the whole. Although new arrivals shouldn’t pursue change simply for its own sake, they should be emphatic about forcing change when necessary. In this regard, communicating often and effectively is vital. Upon replacing a long-serving CEO, the new leaders need to articulate clearly what will change, what will remain the same, and why.

3. Find the right pace for change. Moving too quickly can be as problematic as moving too slowly. Setting the right pace requires resisting arbitrary pressure for you to chalk up fast wins, while moving rapidly enough on the company’s critical priorities to keep things moving forward. Many experienced leaders look back on their years as CEO and feel that they moved too slowly on their company’s critical priorities.

4. Engage the board as a strategic partner. CEOs must leverage the board as a strategic asset, tapping into this insight and experience. In turn, boards today need to own strategic decisions jointly with the CEO; they no longer simply ratify them at an annual off-site meeting.

5. Get the culture working with you. As our colleague Jon Katzenbach notes in his new book, The Critical Few, the informal, emotional elements of the organization are as important as the formal, rational elements. A CEO must understand how these operate and use the organization’s hidden strengths to move the company forward.

Pursuing these agenda items is not an ironclad guarantee of success. And the aggregate data on successions does not dictate the destiny of an individual. Every time a long-serving CEO is replaced, whether it is by an insider or an outsider, the transition is delicate and unpredictable. Still, if boards and leaders are aware of the structural challenges they face at these vital inflection points, they will have a greater opportunity to succeed.

Methodology

The CEO Success study identified the world’s 2,500 largest public companies, defined by their market capitalization (from Thomson ONE) on January 1. We then identified the companies among the top 2,500 that had experienced a chief executive succession event between January 1 and December 31 and cross-checked data using a wide variety of printed and electronic sources in many languages. For a listing of companies that had been acquired or merged, we also used Thomson ONE.

Each company that appeared to have changed its CEO was investigated for confirmation that a change occurred, and additional details — title, tenure, chairmanship, nationality, professional experience, and so on — were sought on both the outgoing and incoming chief executives (as well as any interim chief executives). Company-provided information was acceptable for most data elements except the reason for the succession. Outside press reports and other independent sources were used to confirm the reason for an executive’s departure.

To distinguish between mature and emerging economies, we followed the United Nations Development Programme 2018 ranking. Total shareholder return data over a CEO’s tenure was sourced from Bloomberg and includes reinvestment of dividends (if any). Total shareholder return data was then regionally market adjusted (measured as the difference between the company’s return and the return of the main regional index over the same time period) and annualized.

Author profiles:

- Per-Ola Karlsson leads the organization, change, and leadership practice in the Middle East for Strategy&, PwC’s strategy consulting business. Based in Dubai, he is a partner with PwC Middle East.

- Martha Turner is a leading practitioner in operations for Strategy&. She is a principal with PwC US, based in New York.

- Peter Gassmann is a leading practitioner in the financial-services industry for Strategy&. Based in Frankfurt and Düsseldorf, he serves as managing director of Strategy& Europe. He is a partner with PwC Strategy& Germany.

- PwC US managers Jennifer Bhagwanjee and Spencer Herbst and s+b contributing editor Rob Norton contributed to this article.