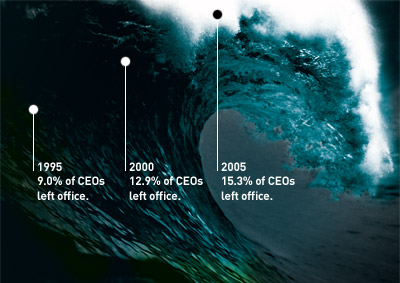

CEO Succession 2005: The Crest of the Wave

Half of all chief executives are dismissed from office, but those who can deliver results are in greater demand than ever.

The year 2005 may mark the crest of a long wave of governance reform that began washing across the global corporate landscape in the late 1990s. This wave has made life more difficult for the stereotypical “imperial CEO” of years past. It has made boards of directors more active and powerful. It has brought some of the previously hidden dynamics of those boards into the light. And it has given shareholders more opportunity to take action against CEOs who consistently underperform. Chief executives who can produce results are in greater demand than ever before. But the difficulties of delivering performance are also greater.

Photograph © Royalty-Free/Corbis. Photo Montage by Opto

The evidence? Global turnover of CEOs set another record in 2005, with more than one in seven of the world’s largest companies making a change in leadership — compared with only one in 11 a decade earlier, according to our annual study of chief executive succession at the world’s 2,500 largest public companies. The rate of outright dismissals was also near its peak: Four times as many of the world’s top CEOs were forced out last year as in 1995. Ten years ago, the CEO’s job was all about “stewardship” of the corporation’s assets for stakeholders; today, it’s all about the bottom line for investors.

There is reason to think that the wave of CEO turnover is cresting, however. The global rates of CEO departures, including CEOs who are fired as well as those who retire or leave as part of a planned succession, are starting to flatten out. Nonetheless, we don’t expect turnover to decline too much. Investors’ focus on performance is here to stay.

Because of heightened performance demands, we sense that a new governance dynamic has begun. This movement aims to proactively change corporate strategies in order to create shareholder value. Institutional investors, private equity firms, and hedge funds are at its forefront. Consider the demand of billionaire investor Kirk Kerkorian that General Motors adopt a radical restructuring plan, or hedge fund manager William Ackman pushing McDonald’s to sell company-owned restaurants. Just as they did in the early days of the 1980s corporate raiders, boards of directors are becoming more engaged with the management of their enterprises. Reacting to the strategies and plans developed by managers is no longer enough for boards. Increasingly, they will be involved in proposing their own value-creating changes in direction.

Booz Allen Hamilton’s annual study of chief executive turnover is now in its fifth year, and it is as relevant to this new governance wave as it was to the previous one. Our unique database of performance over the full tenure of CEOs enables us to assess the impact of the single most important decision a board of directors makes: the choice of a chief executive officer. This year, we focus on the desirability of hiring an experienced CEO; we consider the best background for the chairman of the board; and we examine when to hire — and when to fire — an outsider chief executive.

Our research also illuminates the larger debate on corporate governance that has engaged business leaders, institutional investors, scholars, and policymakers during the past few years. Some business observers have argued that recent institutional, regulatory, and legislative reforms didn’t go far enough; they say that many boards of directors are still too unwilling to replace underperforming chief executives. Other observers suggest that the reforms were overkill and want to roll them back. The CEO succession study provides quantitative data concerning the impact of alternative governance arrangements on share values, and it suggests which characteristics of potential CEOs are most likely to increase a company’s effectiveness.

Among the specific findings for 2005:

-

Governance reforms are working. Boards of directors have become more responsive to shareholder and regulatory pressure, and are more proactive in ousting underperforming CEOs. Of companies worldwide, 15.3 percent (or more than one in seven) replaced its chief executive in 2005. This is the highest level in the eight years we’ve studied and 70 percent higher than in 1995. We believe this turnover level will endure.

-

CEOs are as likely to leave prematurely as to retire normally. Continuing a pattern from 2004, in 2005 nearly half of all CEO departures were due to poor performance or mergers.

-

“Repeat chiefs” are increasingly common. More than one in eight of the CEOs who left office this year had previously served as leader of another company; increasingly, active CEOs are moving directly from one large company to another, a phenomenon we call “beggar thy neighbor.”

-

Outsider CEOs flame, then fizzle. During their first two years in office, CEOs brought in from outside the company produce returns for investors that are nearly four times better than those achieved by insiders. But when the tenure grows longer, insider CEOs tend to do much better. One implication: Companies that hire outsiders should follow a “five-year rule,” seeking a new CEO before performance declines.

-

Nonchairman CEOs are now the best performers. Of CEOs who left office in 2005, those who never served as chairman of their companies outperformed those who served in the dual role of chairman and chief. In North America over the last three years, nonchairman CEOs produced shareholder returns three times as high as those of CEO/chairmen.

-

The former CEO should not remain as chairman. CEOs who serve in an “apprenticeship” model, in which the chairman is their predecessor, generally do poorly. For example, in Europe over the last four years, “apprentice” CEOs produced annual shareholder returns that were 5 percentage points lower than the returns achieved by departing CEOs who had had separate and independent chairmen to work with.

-

In 2005, North America experienced a record level of performance-related turnover, with 35 percent of all departing CEOs forced out. Europe and the Asia/Pacific region (not including Japan) saw declines from their record turnover levels of 2004, which had been triggered by rapid departures of newly hired chief executives.

-

Troubled companies look for outsiders, who don’t necessarily succeed. Among the CEOs who left office in 2005, those who had been hired from outside had taken charge of companies with, on average, far worse performance records than those who had been promoted from within. In North America, for example, 29 percent of the companies with negative performance in the prior two years had hired an outsider versus only 6 percent of positively performing companies.

The New Normal

Booz Allen’s annual study of CEO succession has tracked the rates of global CEO turnover for 1995, 1998, and each year from 2000 to 2005. We identify chief executives at the 2,500 largest publicly traded companies in the world (based on market capitalization as of January 1) who left their positions during the year. Using press reports, public filings, and the companies’ public statements, we classify each departure in one of three categories. First are the “regular” successions, unrelated to the CEO’s perceived on-the-job performance. These include planned departures, long-scheduled retirements, moves to a larger public company, and deaths. Second are the “performance-related” successions, in which the CEO was forced to resign, because of either poor performance or disagreements with the board. The third category is “merger-driven,” in which a CEO resigns or retires after his or her company is acquired by or combined with another. We use public data sources to help us analyze these executives’ tenures as CEOs, including personal demographic data (such as age at ascension and departure) and financial performance of the companies.

In short, this study looks back on the full careers of each year’s “graduating class” of CEOs, and isolates the factors that contributed to the success of some and the failure of others. Each year, we have expanded the number of factors we consider, to uncover additional information about the relationships among boards, management, and corporate performance.

Global CEO turnover set a new record of 15.3 percent in 2005, a rate 70 percent higher than it was 10 years before. All regions experienced high turnover: Japan reached a record level, whereas the other three regions all recorded their second-highest turnover rates. (See Exhibit 1.)

The same global consistency is apparent in the types of turnover. Although only “regular” turnover set a global record in 2005, both performance-related and merger-driven turnover hit their second-highest levels. (See Exhibit 2.) Looking across regions, performance-related turnover set a new record in North America, where 35 percent of CEOs who left office were forced out, and both Europe and Japan experienced near-record levels. Merger-driven successions, reflecting the continuation of a new, robust cycle in M&A activity, were at their highest level globally of any year other than 2000.

Exhibits 1 and 2, in essence, chart one ongoing effect of the recent wave of governance reform — the removal of CEOs who persistently perform poorly for investors. Over the last 10 years, the rates of total CEO turnover and performance-related turnover have risen fairly steadily, with an early peak during the stock market crash of 2000, but then a continued rise.

As important as the trend, however, is the sea change from 1995 to 2005: The firing of underperformers quadrupled. Fewer than half of the outgoing CEOs in the U.S. and Europe left office willingly. There are always a few high-profile cases involving ethics or personal behavior, but the vast majority of those forced out of office were ousted because of poor performance. The transformation this represents in management thinking and business supervision is profound. A decade ago, becoming CEO of a major corporation was the pinnacle of a career, often the reward for a lifetime of service. Chairman as well as CEO, the executive could expect to remain in office until a regular retirement. Consistent with these expectations, two-thirds of departing CEOs in 1995 were 62 or older. The CEO’s focus was stewardship: preserving the company to pass along to his or her successor.

But in 2005 a different model of CEO took hold. CEOs today may still be as well known and well compensated as their predecessors, but now many of them can be terminated like any other employee. Chief but not chairman, today’s typical CEO knows that he (almost all the departed this year were men) will remain in office only as long as performance for investors is acceptable. No longer can the CEO expect to prolong his career by “managing” the board. The CEO’s insider allies typically are gone or less powerful; independent directors meet in executive session to review the CEO’s performance. Except in Japan, a CEO can’t expect to retire in office. Globally, only 40 percent are 62 or older when they leave office.

Finally, since returns to investors reflect the change in a company’s value, the pressure on corporate performance is not focused just on quarterly results, but on sustained growth. Stewardship isn’t an aggressive enough objective for investors. The world of 2005 is much more demanding and uncertain for both companies and their CEOs.

Our hypothesis is that this is the “new normal.” The pressures on companies, and thus on CEOs, will never return to the (already demanding) levels of the 1990s.

Fortunately for CEOs, this also suggests that the decade-long increase in turnover (especially performance-related turnover) will likely flatten out; in fact, it has begun to do so. Practically speaking, CEO turnover can’t increase indefinitely. Some CEOs create considerable value: Investors and the boards that represent them want these CEOs to remain in their jobs. Necessary transformations of companies typically require three or four years. Since the stock market’s initial reactions to the transformations aren’t very accurate predictors of a new chief’s ultimate success, boards are better off waiting a few years to fully assess a CEO’s record before removing him or her for “underperformance.” Otherwise, CEOs won’t undertake essential changes that deliver bad financial news before good. Removal of CEOs before the results of their strategies became apparent would have a chilling effect on innovation and would foster mediocrity. In addition, succession planning is time-consuming and expensive. Boards of directors are likely to recognize all this during the next few years, if they haven’t already.

Logically, then, the rate of CEO turnover should reflect regular departures of CEOs in office for many years plus the merger-driven and performance-related departures of CEOs who last launched a transformation three or four years earlier. Exhibit 3 presents our estimates of the new, normal, logical level of global turnover.

The trends in CEO successions support this hypothesis. For example, we argued last year that turnover in Europe and Asia/Pacific had become unsustainably high, with far too many CEOs forced out in their first two years because of the stock market’s initially negative response — dismissals that occurred before any benefits from the new chiefs’ strategies were apparent. This bloodletting, we believe, reflected the sweeping governance changes in those regions in the late 1990s and early 2000s, which took place before the governance reforms in the United States. CEO turnover in Europe in fact declined from 16.8 percent in 2004 to 15.3 percent in 2005, due largely to fewer premature dismissals. The decline in Asia/Pacific was even larger.

In North America, on the other hand, the governance reforms of 2002 and 2003 in the U.S. — the Sarbanes-Oxley Act’s provisions on board composition and oversight; new rules from the New York Stock Exchange, the American Stock Exchange, and the Nasdaq; and recommendations from private organizations like the Business Roundtable, the National Association of Corporate Directors, and the Council of Institutional Investors — changed the behavior of boards. Total turnover in North America rose from 12.9 percent in 2004 to 16.2 percent in 2005. Many long-serving underperforming CEOs were pushed out, including Peter Cartwright (Calpine), David Goode (Norfolk Southern), Robert Waltrip (Service Corporation International), and Disney’s Michael Eisner (although, to be fair, Disney performed well in Mr. Eisner’s final year).

Once long-standing underperforming CEOs are gone, turnover in North America should stabilize at levels slightly lower than those in Europe and Asia/Pacific. (One reason for the lower North American levels is the disproportionate share of “company builders” in the United States: successful entrepreneurial founders who remain as CEO for more than a decade. These individuals include Larry Ellison at Oracle, Fred Smith at FedEx, and many others.)

Recent governance reforms have produced other improvements. For example, surprised by the rapid uptick in CEO turnover at the start of the millennium, many boards found themselves without attractive succession candidates. However, succession planning has improved, and in both 2004 and 2005 the proportion of outsiders has fallen. (See Exhibit 4.)

The Board’s Dilemma

Because of the increase in CEO turnover, boards of directors have had to spend much more time on succession planning in the past few years. Any board facing the departure of a CEO (whether planned or performance-related) has an array of possible choices, each with its pluses and minuses. The results of this year’s study suggest that three of the most popular CEO recruitment strategies, all of which appear prudent and effective, don’t actually work well in practice.

The first strategy is selecting a “prior CEO,” someone with past experience as chief of another large public company. Some examples of those who left office in 2005 include turnaround specialists (like Jim Kilts, who had led Nabisco before becoming CEO of Gillette); chairmen who were previously CEOs of the same company and retook the position (Phil Knight at Nike); independent directors with former CEO experience who assumed the role (Jack Michaels at Snap-on); and former CEOs whose company had been acquired (Harry Stonecipher at Boeing).

For many boards involved in recruitment, prior CEOs appear to bring two major advantages. Two-thirds of them have a track record of creating superior returns for investors. Moreover, they’ve already mastered the challenges facing a new CEO, such as working effectively with a board of directors, communicating with investors and security analysts, developing and implementing a strategy, and balancing the demands of multiple stakeholders. These are all increasingly difficult challenges because of today’s activist investors and the aggressive tactics put forward by unions and issue advocacy groups. Perhaps because of these ostensible qualifications, the number of CEOs with prior experience has been increasing (at least to judge from our study of those departing). (See Exhibit 5.)

Yet despite expectations, prior CEOs perform slightly worse than new, previously untested CEOs. Although the difference isn’t statistically significant, the pattern — we call it the “old dog syndrome” — has been the same in seven of the eight years we’ve studied.

The message to boards: The presumed benefits of hiring someone with previous experience as a CEO are a mirage. Don’t value that experience as highly as experience in the company at hand, in the industry, or with the types of challenges that must be confronted by your company (and that may well have contributed to the loss of your former CEO).

Beggar Thy Neighbor

The second succession strategy is the hottest recent trend in CEO recruitment: poaching. In this variation of the “prior CEO” idea, boards reach for a currently successful CEO at another of the largest 2,500 corporations. In 2005, Office Depot took Steve Odland from Autozone, Mark Hurd shifted from NCR to Hewlett-Packard, Paula Rosput Reynolds moved from AGL Resources to Safeco, and Martin Flanagan from Franklin Resources to Amvescap. (In Exhibit 5, these “prior CEOs” are included among the “departing CEOs with prior CEO experience.”)

The phrase we use for this approach is “beggar thy neighbor,” since the companies left behind also have to find a new replacement. Indeed, recruitment of active CEOs can cascade across the economy. For example, after scandal forced the ouster of Boeing’s Harry Stonecipher, the aircraft manufacturer hired 3M’s James McNerney; 3M in turn reached for George Buckley, then at Brunswick.

Evidence that this trend is increasing can be found in Exhibit 6, which shows the number of active CEOs who left office each year to take another chief executive position. In 2005, these moves represented about 6 percent of the new CEOs at the 2,500 companies studied.

This strategy may reflect the widely held belief that executive leadership is a generic skill set, not specific to either industry or company. Whether or not that belief is true, our hypothesis is that it will influence behavior in ways that are negative for the global economy. One immediate effect, shown by management scholars such as Harvard’s Rakesh Khurana, is a further increase in CEO salaries — not only the additional compensation required to motivate a chief to change jobs, but also defensive increases in compensation on the part of companies trying to retain their CEOs. Replacing the poached CEO also causes significant disruption and lost opportunities within the raided company, especially while an interim CEO is in place and the new CEO is coming up to speed.

It’s too early to tell whether hiring an active CEO benefits the company doing the recruiting, because too few of these CEOs have completed their career at the receiving company. Because CEO tenure currently averages 7.9 years, the five consecutive years of data we have is too short a time to provide a complete picture of how well these retread chiefs have done. However, if the generally subpar results of prior CEOs hold true for active CEOs hired from other companies — and we think that’s likely — then “beggar thy neighbor” recruiting is a lose–lose: bad for the company and bad for the economy. The likeliest big winners will be the CEOs who move, not only because of their greater compensation but also because of the excitement of mastering new challenges.

Failed Apprentice Model

The third common succession strategy — shifting the chief executive to chairman of the board while promoting a second individual, from inside or outside, to the CEO position — provides another example of a seemingly prudent idea whose benefits are illusory.

This “apprentice model” covers 36 percent of the CEOs who departed in 2005. It is especially prevalent in Japan, where more than two-thirds of the CEOs departing in 2005 had served under a board chairman who was the former CEO. (See Exhibit 7.) In theory, the apprentice model sounds great: Not only does it satisfy the demand of governance activists to separate the role of chairman and CEO, but it keeps the skills and experience of the former CEO available, provides mentoring for the new CEO, and delays the extra responsibility of chairing the board for the new CEO until he or she is up to speed.

Unfortunately, logic fails in the marketplace, at least outside Japan. When we compared the three possible governance models — the combined CEO–chairman; distinct roles, with someone other than the previous CEO serving as chairman; and the chairmanship held by the former CEO — the best-performing companies were those in which the roles were split and the chairman was a true outsider, not the former CEO. This gap between insider and outsider chairman models is consistent in North America and Europe for most of the years we have studied.

The primary reason the apprentice model doesn’t work, we believe, is the inevitable division of responsibility and authority. No matter what the title and what the claims about the division of labor between CEO and chairman, the new chairman at these companies was the chief. For many years, everyone had looked to him. He had set direction for the company, controlled promotions and compensation, and embodied the company’s culture to both employees and external stakeholders. Now in his new position, he has tight links to existing executives, men and women who know how to reach him if they are unsettled by the successor’s strategy or actions. And everyone knows that if the former CEO is unhappy with either the direction of the company or its performance, he might fire the apprentice and take back the CEO title. Can an apprentice CEO realistically drive fundamental change that might well appear to be a repudiation of the past CEO’s actions, especially when disgruntled executives can complain to their former boss?

Moreover, the presumed benefits of retaining the former CEO as chairman are offset by negative effects. Having the former CEO around to offer guidance implies that the new CEO needs additional training and isn’t really qualified to do the job, undermining his or her authority. Letting the former CEO manage the board — a board whose members know the former CEO and were probably appointed by that CEO — hampers the new CEO’s ability to get full understanding and buy-in of his or her change agenda.

An analysis of the shareholder returns for three basic CEO governance models proves that corporations with a separate CEO and chairman, where the chairman wasn’t formerly the CEO, are most likely to succeed. (See Exhibit 8.) These results differ from what we’ve reported in previous studies. Although the insider chairman model has consistently failed, in previous studies the combined CEO–chairman model delivered results as strong as those of the separate model, where the chairman wasn’t formerly the CEO. However, the relative efficacy of the models has changed dramatically over time. Between 1995 and 2001, combining the CEO and chairman roles delivered the best results for investors in both Europe and North America. Subsequently, in every year from 2002 through 2005, separating the roles and appointing a separate, nonexecutive, “never was an insider” chairman has proved to be superior.

Consistent with our conclusion that the former CEO as chairman doesn’t work, the proportion of CEOs operating under this model has declined dramatically over the past decade. In part, the reduction reflects changes in the regulatory regime and the rise of shareholder activism. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act, for example, decreed that a majority of board members be independent, reducing the number of insider slots, and that nominating committees be composed entirely of outsiders. And shareholder activists, increasingly vocal and influential, favor a model in which the chairman is an independent outsider. But the reduction probably also reflects the reality of the poor performance that the model causes. As boards of directors travel along their own learning curves and better represent investors, decisions by boards increasingly reflect what works.

Getting It Right

Choosing between outsider and insider CEOs is another area where some boards are getting it right. Sometimes CEOs recruited from outside are more successful; sometimes those who rose through the ranks within do better. The key indicator of success seems to be their longevity in office. In general, outsiders tend to excel in the short run, whereas insiders tend to perform consistently well over the long term.

This shows up in the study results in several ways. First, outsiders typically perform better than insiders during the first half of their tenure and worse in the second half. (See Exhibit 9.) Second, outsiders achieve consistently higher performance during their first two years in office. Median total shareholder returns are 6.5 percentage points per year higher in North America, for example. Third, insiders generally serve longer than outsiders. In the departing class of 2005, insiders had an average tenure of about eight years, more than two years longer than that of outsiders. The difference in length of service is most pronounced in North America, where insiders’ tenure is about 10 years, almost five years longer than that of outsiders. Finally, when the time in office stretches past 14 years, only a handful of outsiders remain — in North America or elsewhere — and they deliver consistently lower results than their insider counterparts. Globally, 72 percent of long-service insiders delivered returns above their regional average in 2005, compared with only 54 percent of the long-term outsiders.

Why the differences? Perhaps it’s because outsiders excel in shaking up a company: setting a different strategic direction, demanding higher levels of performance, reducing costs, disposing of underperforming assets, and communicating with investors. They bring more objectivity and a willingness to slaughter sacred cows, they benefit from outside business experiences, and they’re often hired by a board anxious to make major change. All of this gives them an edge in fast turnarounds.

Insiders, meanwhile, excel at driving long-term profitable growth and stimulating lasting change in a company’s culture and relationships. (The only region where outsiders perform well in the second half of their tenure is Europe, where a premium is placed on long-term stakeholder relationships, such as those with labor unions and community groups.) Insiders may also have a deep understanding of customers, technology, and operations gained through their years within. Although the initial benefits of an insider CEO’s skills may not be apparent for three or four years, they are evergreen, potentially yielding benefits over and over again throughout their CEO career.

In addition, outsiders are more likely to inherit companies performing poorly — 5.3 percentage points worse for investors over the two years prior to selection of the new CEO than is the case for companies where insiders are appointed. Much of the difference is social. Insiders are known; they are products of the company and its culture, and they unquestionably understand what’s distinctive and valuable about the company. Outsiders are, well, outsiders. Employees and channel partners are suspicious that the outsider will just cut costs to boost margins in the short term (and, perhaps, to prepare the company for a sale). No wonder outsiders excel at big structural changes, like cost reduction and asset sales, that deliver value to investors in the first three or four years but don’t require the kind of organizational and cultural transformation that may deliver increased value over the long run.

One implication of the pattern of insider/outsider performance for boards of directors is the “five-year rule”: Boards that hire a CEO from the outside should plan for the chief’s tenure to last about a half decade. A series of outsiders, each hired to lead a specific transformation and each remaining in office for four to five years, could prove even more effective than long-term insiders. Companies like Yahoo, where Terry Semel followed Tim Koogle, and Qwest, where Richard Notebaert replaced Joseph Nacchio, are testing the viability of a series of outsider-driven transformations. To be sure, this kind of strategy requires a different kind of planning. Boards could focus on recruiting only the skills needed by a CEO in the next five years, but then would have to begin recruiting or grooming a successor almost as soon as the new CEO is hired.

Governance’s Next Wave

Governance reforms to date have addressed the “agency problem,” the innate conflict between the interests of owners (investors) and those of managers, even though managers are ostensibly acting in the shareholders’ interests. As early as the 1980s, leveraged buyouts targeted companies ripe for restructuring, singling out in particular those chief executives who had stockpiled cash to insulate their companies from the discipline of the stock and bond markets. More recently, the wave of governance reform described above has pushed boards to move more quickly to remove underperforming CEOs.

Because these reforms have been successful and boards of directors have stepped up to advocate on behalf of shareholder interests, we feel that the most deleterious aspects of the agency problem have been addressed. Some governance activists will lobby for additional expansions of shareholders’ authority, for example, declaring that resolutions that receive majority support will be binding upon boards, or requiring shareholder votes on merger offers. However, the proposals we’ve seen for expanded governance reform do not seem to be clearly in the interest of shareholders, much less other stakeholders, and skillful boards will learn to circumvent the rules.

In any case, corporate governance issues are increasingly shifting away from agency-related issues and toward strategic issues. Boards will become more deeply involved in creating value by helping management better identify threats and opportunities, by supporting management’s efforts to effect major change, and by enhancing the quality of the management team. Although self-confident CEOs invite their boards to perform these tasks today, management typically leads in formulating strategies and plans, and the board reacts. That won’t last: In today’s demanding, rapidly changing world, a reactive role for the board isn’t enough. An effective board is better equipped than are institutional investors, hedge fund operators, or private-equity firms to ask probing questions and suggest value-creating changes in strategy or organization.

During the past decade, successful companies have learned to mobilize the best thinking of employees at all levels. The next governance wave will enlist the full insights and experience of the board of directors as well, fundamentally changing the governance relationship between management and the board, and requiring much greater involvement by directors. The companies that thrive in this environment will be those in which the CEO and the board maintain a healthy level of tension, while keeping their eye on the long-term growth of the enterprise. Without returning to the “imperial CEO” of the past, such companies will also avoid the costs and turbulence of a high CEO turnover rate.![]()

|

Which Way after M&A? |

|

During the early years of this decade, merger activity declined along with the stock market. But now, with good reasons appearing for companies to use mergers and acquisition for growth, the number of merger-related CEO departures is again on the rise. (See “Mergers: Back to Happily Ever After,” by Gerald Adolph, s+b, Spring 2006.) One in six of this year’s departing CEOs lost his or her job after a merger or acquisition. What becomes of these former CEOs? More than half (54 percent) move on, either to a new company, into consulting, or simply into retirement. The rest, however, stay with the acquirer. About half of these survivors take on an advisory role, serving on the board of directors or staying on as an internal consultant during the transition. But notably, the other half take a substantive operational role, typically either as the head of a division or in a key functional position with line management responsibilities. When WellPoint acquired the regional player WellChoice, for example, ex-WellChoice CEO Michael Stocker agreed to remain as CEO of the newly combined company’s Northeastern U.S. regional operation. Similarly, after United Technologies took over Kidde, former Kidde CEO Doug Vaday agreed to stay on as president of the fire safety division. Why do so many former chiefs stay on? There are three reasons. First, being acquired by a larger company may be a passport to greater opportunity, even for executives who are losing their CEO title. Both Mr. Stocker and Mr. Vaday ended up running operations larger than the companies they had presided over before. Second, CEOs may stay with the acquiring company because there is a reasonable chance that they could move on to the chief executive role of the larger company in the future. For example, when News Corporation acquired Fox Entertainment, Fox CEO Peter Chernin took the role of president Gerald Adolph (adolph_gerald@bah.com) is a senior vice president in Booz Allen Hamilton’s New York office, where he specializes in mergers, restructuring, and integration. |

|

Strategies for the Newly Engaged Board |

|

Corporate directors facing a departing CEO (whether the departure is planned or performance-related) have an array of choices. The results of the 2005 CEO Succession study suggest that some of these strategies will work better, on average at least, than others.

|

|

The Japanese Exception |

|

Although the age of the “imperial CEO” has ended across most of the globe, Japan is another story. At nearly 20 percent, the overall rate of CEO succession in Japan is at an all-time high, and at first glance seems to be in line with succession rates in the United States and Europe. But Japan is unusual in its exceedingly low rate of forced successions. This year, for example, only 10 percent of all CEO successions were forced in Japan, compared with 35 percent in the U.S. and 42 percent in Europe. As Hiroyuki Sawada, Booz Allen Hamilton’s lead representative in Japan, suggests, “While there is a trend in Japan toward more corporate transparency, including appointing outside board members, there remains a long and significant history of weak governance and CEO supremacy.” The lack of forced succession reflects Japanese corporate culture, which has favored continuous leadership as a strategy, particularly as it emerged from the national recession of the 1990s. Most Japanese corporations follow the “apprentice model” of CEO succession, in which the current CEO is promoted to chairman after naming his successor. In 2005, 69 percent of departing Japanese CEOs were apprentices, down from 97 percent in 1995. Although the decline indicates some trend toward stronger corporate governance in Japan, 69 percent is still a very high number, especially when compared with the U.S. and Europe, where 36 percent and 22 percent, respectively, were apprentices in 2005. In Japanese practice, the apprentice model usually means that the newly promoted chairman calls the shots and the CEO implements the chairman’s strategy, effectively making the newly named CEO a deputy. For most CEOs in Japan, the goal is therefore to become chairman, and that requires patience. Unlike CEOs in the rest of the world, Japanese CEOs have full authority to name their successors, which is typically a private, personal, and politically motivated decision. Thus, if the CEO successfully carries out the chairman’s objectives and performs well, he is almost always rewarded with the chairmanship and the eventual ability to name his own successor. The board will step in only in situations where the CEO is significantly underperforming. With Japan’s regular departing CEOs producing the overall lowest regional total shareholder returns — 1.7 percent versus a global average of 6.5 percent — more boards may step in and name CEO successors, though at a pace that is amenable to Japan’s more patient culture. — C.L., P.K. |

|

Methodology |

|

This study required the identification of the world’s 2,500 largest public companies, defined by their market capitalization on January 1, 2005. We use market capitalization rather than revenues because of the different ways financial companies recognize and account for revenues. Thomson Financial Datastream provided the market capitalization of the top companies in each global region on December 31, 2004. For analytical purposes, we divide the global market into six regions: North America (the U.S. and Canada), Europe, Japan, Rest of Asia/Pacific (including Australia and New Zealand), Latin America (including Mexico), and Middle East/Africa. To identify the companies among the top 2,500 that had experienced a chief executive succession event, we used a variety of printed and electronic sources, including Corporate Yellow Book and Financial Yellow Book (both published by Leadership Directories); Fortune; the Financial Times; the Wall Street Journal; and several Web sites containing information on CEO changes (www.ceogo.com, www.executive-select.com, www.hoovers.com, and www.spencerstuart.com). Additionally, we conducted electronic searches using Factiva, Nexis, and general search engines for any announcements of retirements or new appointments of chief executives, presidents, managing directors, and chairmen; results of these searches were compared with the list of top 2,500 companies. For a listing of companies that had been acquired or merged in 2005, we used Bloomberg. Finally, we utilized marketing personnel of Booz Allen Hamilton offices outside the United States to add any CEO changes in their regions that had not been identified. Each company that appeared to have experienced a CEO change was then investigated for confirmation that a change had occurred in 2005 and for identification of the outgoing executive: name; title(s) upon ascension and succession; starting and ending dates of tenure as chief executive; age; education; whether he or she was an insider or outsider immediately prior to the start of tenure; whether he or she had served as a CEO of a public company elsewhere prior to this tenure; and whether the CEO had been chairman and, if so, for how long. We also ascertained the identity of the chairman at the start of the CEO’s tenure (if different) and whether that individual had been the CEO of the company, and the true reason for the CEO succession event. Company-provided information was acceptable for each of these data elements except the reason for the succession; an outside press report was necessary to confirm the true reason for an executive’s departure. We used a variety of online sources to collect this information on each CEO’s tenure, including company Web sites, the Factiva database, www.transnationale.org, and proxy statements available on the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission’s EDGAR database (for U.S.-traded securities). In some cases, when the online sources were unproductive, we contacted the individual companies by e-mail and telephone to confirm the tenure information. We also enlisted the assistance of Booz Allen offices worldwide as part of this effort to learn the reasons for specific CEO changes in their regions. We then calculated average growth rates (AGRs) of total shareholder returns (TSRs), including the reinvestment of dividends, if any, for each executive’s tenure. We did this for total tenure, first and second halves of the tenure, first two years, and final year. To assess the company’s health prior to each CEO’s tenure, we collected TSRs for the five years prior to each CEO’s start date and calculated AGRs. TSR data was provided by Thomson Financial Datastream. We calculated regionally adjusted TSR AGRs by subtracting the Morgan Stanley regional shareholder return indices (and Datastream regional industry shareholder return indices) from the company’s performance during the time periods in question. |

Reprint No. 06210

Chuck Lucier (chuck@chucklucier.com) is senior vice president emeritus of Booz Allen Hamilton. He is currently writing a book and consulting on strategy and knowledge issues with selected clients. For Mr. Lucier’s latest publications, see www.chucklucier.com.

Paul Kocourek (kocourek_paul@bah.com) is a senior vice president with Booz Allen Hamilton in San Francisco. He focuses on strategic transformation, corporate governance, and leadership issues for mid-sized to large corporations.

Rolf W. Habbel (habbel_rolf@bah.com) is a senior vice president with Booz Allen Hamilton in Zurich, and author of The Human Factor: Management Culture in a Changing World (Palgrave Macmillan, 2002). He focuses on the leadership and performance issues of large corporations.

Also contributing to this article was Julien Beresford, president of Beresford Research.