China’s herd of unicorns

About 200 Chinese startups have valuations of $1 billion or more, and many are preparing to go global.

A version of this article appeared in the Winter 2019 issue of strategy+business.

James Zhu knew the time had come to join Fanli as full-time chief operating officer in 2010, when the Shanghai-based startup first began to raise money. At the time, Fanli was an online shopping rebates service cofounded by an acquaintance, Gary Ge Yongchang, who ran it from his apartment’s living room. The startup period was difficult; China’s e-commerce market was still immature. The company had just two servers, one for the website and one for the database. Online speed was glacially slow. Fanli’s employees walked up and down Shanghai’s streets handing out cards to drum up interest. Ge initially paid out rebates using his personal credit cards.

Zhu was only helping out Fanli part-time; he had a senior role in the Shanghai office of Corel, a Canadian software company. “I had a great job,” he recalls. “I had a driver, oversaw a team of 200 people, and was paid quite a bit.” But institutional investors convinced him to come onboard as Fanli’s full-time chief operating officer. “They wanted me to have skin in the game,” he says. Within a year, he joined, and Fanli raised US$10 million in Series A funding (its first round of venture capital finance).

Nine years later, Fanli has grown into one of China’s largest e-commerce websites — an online directory and “flash event” company that matches Chinese shoppers with marketers from around the world, helping people find their most-desired goal (as Ge has been known to state it): “value for money: the best products at the lowest prices.” Fanli’s story is typical of about 200 rapidly growing Chinese “unicorns,” enabled by leading-edge digital technology, the burgeoning Chinese middle class, new capital-raising opportunities in Shanghai and elsewhere, and the enthusiastic entrepreneurialism of their founders.

The standard definition of a unicorn is a privately held startup valued at more than $1 billion. Currently, when people think of Chinese unicorns, they think of the handful of companies that have risen to global status in two decades or less: companies such as Alibaba, Baidu, JD.com, and Tencent. Since these few are already valued at $10 billion or more, they are now known as “superunicorns.” Many more Chinese unicorns are coming up behind them, still relatively unknown because they currently operate only within China, which is large enough to sustain them for some time. But sooner or later, many of this second wave of Chinese unicorns will grow into global industry giants.

Why Chinese unicorns grow

Companies like Fanli were once as elusive as their mythical namesakes. Just 39 unicorns existed in the United States in 2013, when Aileen Lee, founder of Silicon Valley investor Cowboy Ventures, coined the term. Now there are at least 334 around the world, with a combined valuation of more than $1 trillion. In China, as the Internet era has transformed business, unicorns have been created at an accelerating rate. Only the U.S. has as many as China. According to the May 2019 Greater China Unicorn Index from Shanghai-based research firm Hurun, there are currently more than 200 such companies in China (by comparison, the U.S. has more than 300), 21 of them having entered the ranks in the first quarter of 2019 — almost one per week. Hurun estimates that one-fifth of today’s Chinese unicorns will fail, one-tenth will be acquired, and most of the rest will go public successfully.

In mid-2018, to shed light on the unicorn phenomenon and its impact, PwC surveyed the chief executives of 101 young, successful Chinese companies — companies that either are unicorns now or are likely to become unicorns soon. These executives described the factors affecting their fast-growth businesses and their own prescriptions for success. Augmented since then with follow-up research, including in-depth interviews with the leaders of several of these companies, these results shed light on the nature of this new phenomenon, and the impact that Chinese unicorns are likely to have, in China and around the world.

Unicorns are prevalent in at least 13 industrial sectors, with the largest numbers in four industries significantly shaped by technology: enterprise services, media and entertainment, transportation and automotive, and fintech (digital financial technology services). Examples in these sectors include ManBang Group, a pioneer in truck hailing; Meicai, a B2B platform for the agriculture industry; ByteDance, the developer of the content platform Toutiao and the popular 15-second video app TikTok; Yitu, which provides artificial intelligence (AI) services to business; Tuhu, which connects people to car-related services online; and the online brokerage Tiger Brokers. Close behind in the sector rankings are e-commerce startups, online-to-offline (O2O) businesses enabling online purchasers to pick up products in person or receive goods and services delivered instantly, and healthcare enterprises, with an emphasis on biotech.

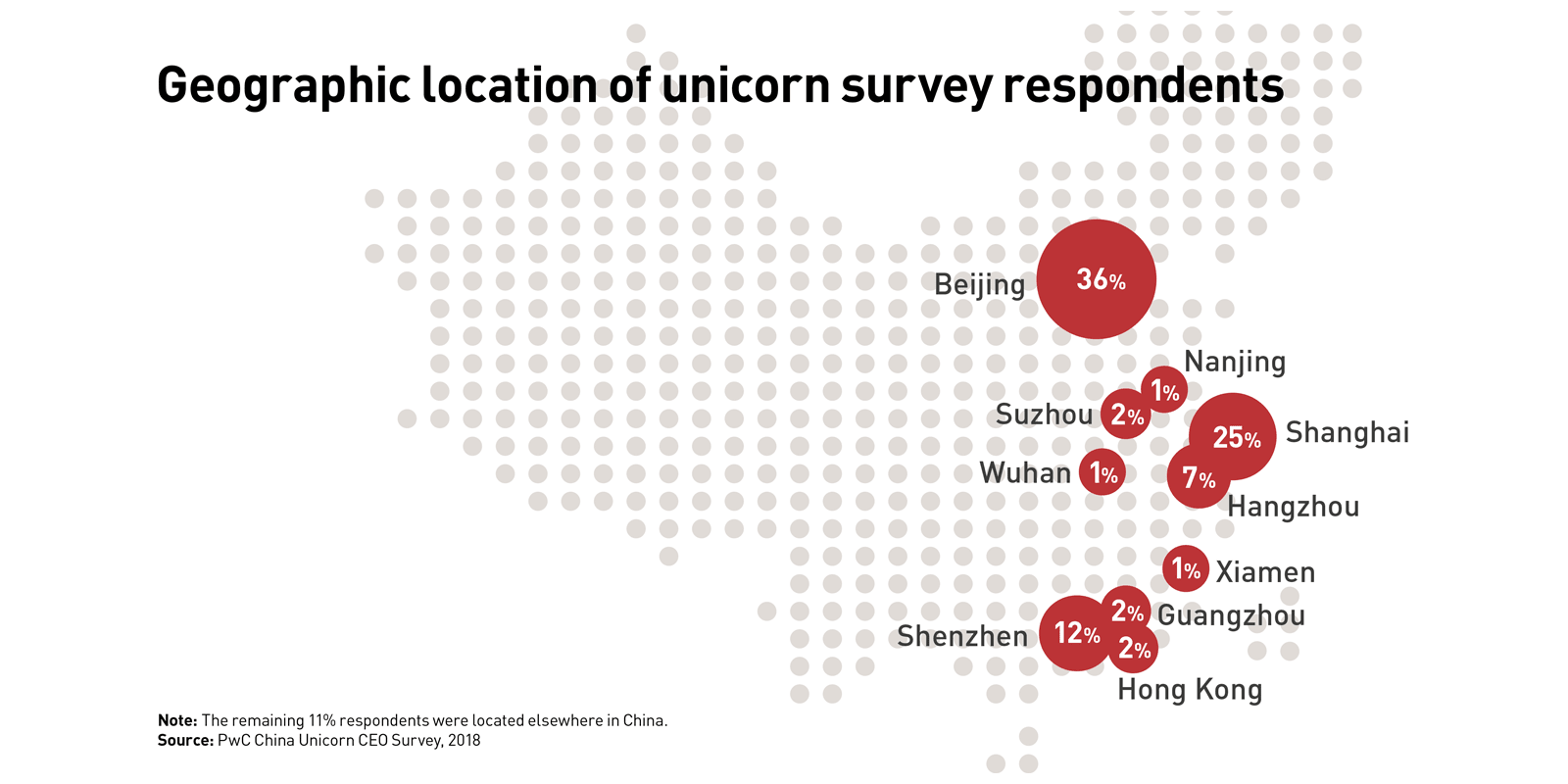

The survey also seems to confirm the rapid growth rates of these companies. Of those leaders who disclosed financial information, 83 percent said revenues had increased by more than 50 percent in the previous fiscal year; more than half of that group said revenues had more than doubled. Most unicorns, of course, are privately held businesses, a model that can be conducive to rapid growth. As with industry everywhere, Chinese unicorns gravitate to large cities with skilled talent; 80 percent are headquartered in Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, or Hangzhou. Like many of their Silicon Valley counterparts, they are tapping into new types of venture capital and other financial resources that might not have been available in the past.

One major advantage that Chinese unicorns enjoy is their near-exclusive access to a huge and vital domestic market. China is full of newly prosperous consumers with improving standards of living who are largely out of reach for companies from other economies. Consumer expenditures accounted for nearly 80 percent of overall economic growth in China in 2018, up from 58 percent in 2017, according to the National Bureau of Statistics. China’s consumers are also relatively technologically advanced. Online retail sales there have ranked first in the world since 2013, with the U.S. in the second position; in 2018, China’s online sales reached $1.33 trillion (just over ¥9 trillion), an increase of almost 24 percent over 2017. The mobile Internet is particularly important in China, where 800 million people, out of a total population of 1.4 billion, use handheld phones or devices to connect.

The rise of startups with $1 billion-plus valuations is regarded as an indicator of the continued strength of China’s domestic consumer economy, regardless of what happens to overseas trade or economic policy. Technological innovation is transforming the way people shop, travel, invest, eat, and choose entertainment. The generation born in the 1980s and 1990s is China’s most influential buying group, creating demand that fuels new business opportunities. Consumers are technologically adept and are interested in personalized, convenient, and AI-enhanced products and services.

“The market is big,” says Zhu. “It has so much imagination and so much possibility…it is going to be able to support much bigger businesses.”

In Beijing, Shanghai, and other major Chinese cities, it is often significantly cheaper to have food delivered than to get it yourself, especially with O2O unicorn companies such as China Internet Plus (formerly Meituan-Dianping), Ele.me (purchased in 2018 by Alibaba), and Luckin Coffee (which delivers hot drinks to homes and offices). In many cities, electronics and groceries can arrive within hours of an order. Millions of Chinese people are becoming sophisticated consumers who can have a wide range of products or service providers, such as barbers, arrive at their door.

The mastery of digital technology is another key factor in these companies’ growth. Of the executive respondents, 76 percent identified big data as one ofthe most influential emerging technologies for business development and product innovation. AI ranked second, with 67 percent. Other emerging technologies that scored high were cloud computing (42 percent), the Internet of Things (37 percent), and 5G wireless transmission (34 percent). Blockchain, robotics, bioscience, virtual and artificial reality, and quantum science were all cited by fewer than 20 percent of respondents, and unmanned aerial vehicle technology was named by only 4 percent.

Some unicorns, such as the facial recognition software maker SenseTime, are breaking new ground technologically. SenseTime, which has been called the world’s most valuable AI startup, was developed “out of the computer vision lab at the Chinese University of Hong Kong,” writes Rebecca Fannin in her forthcoming book, Tech Titans of China. “In China, about one-third of its customers are in the public security sector.… The client list also includes Chinese smartphone makers Xiaomi and OPPO, social networking service Weibo, Hainan Airlines, and payment systems China UnionPay. Outside of Mainland China, SenseTime has established a subsidiary in Japan to work with Honda to develop autonomous driving.” Fannin quotes CEO Xu Li, from a talk he gave at an entrepreneurial summit: “The world is facing East…. [In the past] we relied on the West for advanced technology and industrial modes. Now we must embark on a treasure voyage to better service other industries with advanced technology.”

Long-range aspirations

Many Chinese unicorns aim to go international over the next decade. More than 70 percent of the leaders of Chinese unicorn companies say they already have plans or strategies for overseas expansion. This is in part thanks to government encouragement: China’s Belt and Road Initiative emphasizes international “innovation-based open cooperation,” and China has introduced a series of measures to create a favorable environment for innovation. At first, most unicorns will probably stay rather close to home; their preferred locations are the Asia-Pacific region (31 percent), regions covered by the Belt and Road Initiative (19 percent), and North America (18 percent). But many may attempt to become full-scale global enterprises, either on their own or in partnership with companies from other regions.

When it comes to growth, in fact, most of the unicorn leaders say they value independent, long-term development over flipping their companies for immediate gain. They want to create tomorrow’s great global enterprises; they’ll countenance an initial public offering (IPO) or alliance if it furthers those goals. For example, nearly half of the companies, 48 percent, planned to acquire outside businesses, but only 6 percent planned to be taken over by other companies.

Raising capital to keep up with rapid growth requirements is thus a priority for nearly all the unicorns. Of the 101 survey respondents, 80 percent said they expected to undertake a new round of financing during the next two years. Within this group, nearly one-third — representing a quarter of the survey’s total respondents — said their plans for financing were urgent. Many will seek private equity funding or venture capital.

Asked to name the most important factor when choosing investors, only 20 percent of the unicorn leaders said valuation. More respondents named the investors’ brand value (24 percent) or the business and traffic they brought in (22 percent). The top 10 institutional investors providing capital to Chinese unicorns, ranked by the number of these companies they invested in, are Sequoia, Tencent, IDG, Matrix, Alibaba, Shunwei, Warburg Pincus, Qiming, Morningside, and Baidu. This is a diverse group, and it includes three institutional investors (Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent [BAT]) that are first-generation superunicorns themselves. The BAT investments are noteworthy: 23 percent of the Chinese unicorns have received funds from at least one of these three superunicorns.

As for public financing, PwC’s survey found few companies had immediate plans for an IPO. Of the enterprises that disclosed information in the survey, nearly two-thirds had plans to list within two years. But within this group, only 21 percent said their IPO would happen as soon as possible. Another 44 percent had plans to list but without the same urgency, and the remaining disclosing companies had no plans to list. The survey, conducted in 2018, identified Hong Kong as the most desirable destination to list, with 43 percent of the vote, and the U.S. and the Chinese Series A market trailed with 25 percent and 23 percent, respectively.

Fortunately for the companies that want to go public, China’s capital market system is evolving to accommodate them. For example, the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKEX) has developed an option for weighted voting rights, which are friendlier to startups, along with new rules designed to open doors to biotech companies that may not see direct revenues for several years.

The Chinese government has also signaled strong interest in luring technology-oriented businesses back to stock exchanges in mainland China, even if this means relaxing some of its vetting practices. Additionally, China launched a Nasdaq-style exchange, the Science and Technology Innovation Board, in July 2019, focusing on four sectors: biomedicine, materials, energy, and IT. On the first day, the 25 companies that listed IPOs gained, on average, 140 percent of their initial share price.

One of the most critical questions in financing is how long the investors must wait for companies to become self-sustaining businesses. Thirty-five percent of the unicorns surveyed had already made profits, and another 27 percent expected to start turning a profit within one to three years. Twenty-five percent did not disclose this information.

Entrepreneurial spirit

Though China is not always viewed in the West as an entrepreneurial culture, the unicorn leaders are tapping into a way of thinking that has been present for most of its history. “Traditionally, Chinese people have been starting their own businesses since ancient times,” says Shen Haiyin, founder of Singulato, a startup automaker. “In Japan, after graduating from college, most students prefer to work for big companies, such as Sony and Toshiba. But a bigger proportion in China join startups or start their own businesses.” Ambitious tech entrepreneurs see other companies reach a billion-dollar valuation and think “Why not me?”

The leaders of China’s unicorn companies cultivate an energetic, entrepreneurial frame of mind. Figures like Alibaba’s Jack Ma and Xiaomi’s Lei Jun are continually profiled and widely admired; startup experience is highly valued by investors and talent recruiters. Fully 70 percent of the founding members of unicorns have two or more startups already under their belt. As in Silicon Valley, unicorns favor the young: 88 percent of the survey respondents were in their 30s and 40s, and for 72 percent of the surveyed companies, the average employee age was under 30. The ability to manage and motivate younger employees is thus at a premium.

The companies are growing fast, in part, because their leaders feel they don’t have time to grow slowly. Three-quarters of the responding companies in PwC’s survey had been in business for less than eight years, and one-quarter of the respondents said their company was less than four years old. These leaders build their businesses around engaging user experience. Like tech companies everywhere, they emphasize speed and rapid, continuous improvement. They release products before they are fully tested, change their business models quickly as they learn from customer data (an app will typically have millions of users), lock up distribution partnerships early on, and use social media strategically. They do not hide their ambition to become champions of their market sectors, and in many cases they feel driven to launch entrepreneurial businesses just to survive in the high-pressure world of the Chinese middle class.

Like tech companies everywhere, Chinese unicorns release products before they are fully tested, change their business models quickly, and use social media strategically.

“The restlessness comes from social competition,” says Zhu at Fanli. “People here are very anxious. They tend to feel, ‘If I’m just going to work the way that was planned out for me, I’m not going to get where I want to go. So I want to take shortcuts. I want to try new things.’”

Although the automotive industry is generally more mature elsewhere, in China it is the domain of startups. By some estimates, new Chinese auto manufacturers have raised a combined $18 billion since 2011; the companies include Aiways Auto, Leap Motors, NIO, Singulato, WM Motor, and Xpeng Motors. Government support for the electric vehicle (EV) sector — through subsidies for automakers and buyers, favorable lending, and tax breaks — has created a significant tailwind for these companies. China recently announced cuts to these subsidies, but it is still under pressure to combat smog, boost its own auto industry, and reduce its reliance on imported oil.

Singulato, founded in 2014 in Beijing, is typical of the group in its stated ambition: to build a car for China’s smartphone generation. The company, whose name combines singularity (referring to an evolutionary threshold anticipated by some AI pioneers) and auto, is one of the biggest fundraisers in the crowded EV market. The company’s EVs are aimed mainly at young, tech-savvy consumers in Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, and other large cities where buying a gasoline-powered car is becoming more difficult because of purchase restrictions imposed by the government. The first offering is a connected electric sport utility vehicle, and Singulato plans to evolve, in part through software-driven upgrades, toward autonomous vehicles.

Shen, Singulato’s founder, had never worked in the auto industry before launching the company. A fluent Japanese speaker, he cofounded JWord, a Japanese-language keyword-based Internet guide site, which he sold to Yahoo Japan in 2007. He then joined Kingsoft, one of the oldest Chinese software companies, before launching Singulato.

“Singulato is trying to seize the historical opportunity, like when China started shifting from functional phones to smartphones,” says Shen. “We’re trying to build a smart EV to lead the industry from the traditional functional car to a truly smart car.”

Living with Chinese unicorns

Some observers are skeptical about the future of Chinese unicorns. A recent article cited trade tensions and fluctuating investment levels to argue that many of these fast-growth tech companies may falter. Nonetheless, the overall impact — as with all issues related to Chinese commerce — could be far greater than expected, because of the scale of activity.

For example, Chinese unicorns will compete for talent. Competing for skilled employees is already a priority for 77 percent of the companies surveyed, and as they grow, that will increase, particularly in emerging technologies such as AI and blockchain. As the Singulato example suggests, unicorn leaders are increasingly interested in global opportunity in a variety of industries — as opposed to primarily producing online systems and apps for the Chinese market.

When a large number of companies attract valuations of more than $1 billion after just a few years, it changes the nature of the economy. Unicorns will develop in other places; India already has a number of rapidly growing startups, and the United States is not expected to lose momentum.

China’s new unicorns will face numerous challenges, particularly as they grow and their need for talent and other resources scales up. They will increasingly find success by relying on managerial skill and effective use of the resources they possess. Not every Chinese unicorn will succeed; rivals may emerge to challenge or compete with them. But their rapid growth and global ambition suggest that they will not be unknown for long.

Author profiles:

- Jianbin Gao is the managing partner of technology, media, and telecommunications industries for PwC China.

- Yuqing Guo is a partner with PwC China in its China Centre of Excellence.

- This article is adapted and expanded from “The new Chinese unicorns: Seizing opportunity in China’s burgeoning economy” (PwC, 2018).

- Also contributing were Sanjukta Mukherjee, head of thought leadership for PwC China; Lan Lan, manager of thought leadership for PwC China; and contributing writer Colin Shek.