The Man Who Made the Computer Age Possible

Intel’s Andy Grove pioneered high-stakes, high-speed, high-tech manufacturing — and breathed life into Moore’s Law.

A version of this article appeared in the Summer 2016 issue of strategy+business.

Excerpted with permission from From Silk to Silicon: The Story of Globalization Through Ten Extraordinary Lives, by Jeffrey E. Garten (HarperCollins, 2016)

In From Silk to Silicon, a colorful history of globalization, Jeffrey E. Garten, former dean of the Yale School of Management, has identified 10 people who fundamentally changed the world over the past millennium by making it smaller, more connected, and otherwise better. The roster of characters includes military genius Genghis Khan and Cyrus Field, the pioneer of the trans-Atlantic telegraph. The individuals profiled were not just thinkers — they were doers. And each ushered in an age that continues to echo loudly today. In the following excerpt, Garten tells the story of the Silicon Valley pioneer and former Intel CEO who passed away at age 79 on March 21, 2016, and “the person most responsible for putting Moore's Law into practice.”

Andy Grove was not a pathbreaking scientist. He did not author anything so important as the law associated with Gordon Moore. He was never a household name like Bill Gates. Unlike Steve Jobs, he was not a design genius, nor did he have the same intuition for consumer sentiment. But no person had as much to do with making possible the third industrial revolution as this Hungarian immigrant who arrived in the U.S. in 1956.

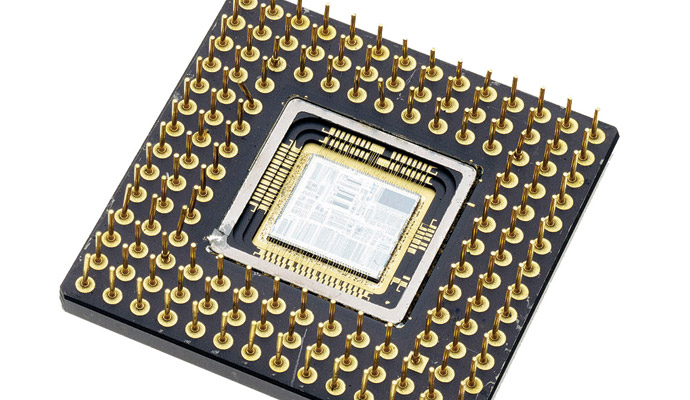

The first industrial revolution began in late 18th-century England with the mechanization of the textile industry. The second took off in early 20th-century America with innovations such as the assembly line and mass production. The third — the one we’re living through today — gestated in Silicon Valley, and is powered by communications technology, particularly the Internet and digitization. The driving force behind this latest industrial revolution is the tiny microprocessor, the closest thing to the brains of a computer. Historian John Steele Gordon has called the microprocessor the most fundamental new technology since the steam engine.

It is unappreciated just how much the very industrial process of making the devices has contributed to contemporary globalization. In large part, the computer age arrived as a result of a revolution in the management of high-technology industries. Andy Grove was the leader of that revolution. An Eastern bloc disciplinarian with modish sideburns and a clunky hearing aid, Grove whipped a motley crew of early industry pioneers at a startup into the world’s most important and global technology company: Intel. He built the products — the semiconductors, the transistors, the integrated circuits, the microprocessors — that drove the consumer electronics revolution. And he gave us a vivid picture of how to survive and thrive in business when the only constant is mind-bending change.

Grove became famous for urging his staff to maintain an attitude of acute paranoia toward Intel’s rivals. He traced his natural anxiety to his experience as a child. Grove was born András Gróf on September 2, 1936, in Budapest, an inauspicious time to be a Jew in Hungary. In 1942, András’s father, George Gróf, a partner in a small dairy business, was conscripted by the fascist Hungarian government, which sent him to the Russian front. For years, Andras’s mother Maria shuttled her son between their apartment and a friend’s house in the countryside, trying to avoid the war between the Germans and the Russians, not to mention the German search to round up Jews for eventual extermination.

At the age of 4, András had contracted scarlet fever, which permanently damaged his hearing. To compensate, he learned to lip-read and would always sit in the front of the class. Over the next 20 years, he would undergo five reconstructive ear operations. In the postwar years, Gróf developed into a good student, and was interested in pursuing journalism. But after 1952, when the Soviets began clamping down on free expression, András turned his interest to chemistry, a profession less susceptible than journalism to capricious interference from Communist mandarins.

In 1956, after Soviet tanks rolled into Budapest to crush an incipient revolution, András’s aunt, an Auschwitz survivor, urged her nephew to escape immediately. George gave him the name of a cousin in the United States. And András, with nothing but the clothes he was wearing and a knapsack, set out with two friends. They crossed the Austrian border by foot, made their way to Vienna, and received permission to go to America. After crossing the Atlantic in a rusty U.S. troop carrier, he moved in with his cousins in Brooklyn, N.Y. András, who would change his name to Andrew Grove, entered Brooklyn College and soon transferred to City College of New York. He graduated first in his chemical engineering class, and married Eva Kastan, an immigrant from Austria, who had come to the U.S. after living many years in Bolivia. After earning a Ph.D. at the University of California at Berkeley in 1963, he took a job at Fairchild Semiconductor in the town of Mountain View, south of San Francisco.

The Roots of a Revolution

Having escaped a violent political revolution, Grove found himself at ground zero of a peaceful technological one. After World War II, scientists at Bell Telephone Laboratories, including William Shockley, invented the transistor — a tiny metal slab that was much smaller and more powerful than the vacuum tubes that powered the earliest computers.

In 1954, Shockley set up his own semiconductor lab, Shockley Semiconductor, in an old shed outside Palo Alto and recruited some of the best minds from around the country, including Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore. But the company was plagued by problems. Customers such as the Department of Defense and IBM required a highly reliable and repeatable process for mass-producing ever-smaller transistors. And although Shockley showed an ability to create pathbreaking technology, he lacked the managerial skills to produce reliable devices in large quantities. Worse, Shockley’s autocratic and narcissistic temperament led him to ignore or reject any proposal that was not his own.

Noyce and Moore started looking to break away and start another company. Sherman Fairchild, an eccentric, wealthy playboy and entrepreneur who had founded the Fairchild Camera and Instrument Corporation, agreed to bankroll the defectors. They set up Fairchild Semiconductor in Mountain View, Calif., about two blocks from Shockley’s operation. The defectors from Shockley came to be known in Silicon Valley as the “Traitorous Eight.”

It was an ideal time to start a new technology business. In 1957, the space race between the United States and the Soviet Union had elevated the microelectronics business to national prominence. Fairchild began to achieve pioneering breakthroughs, including the discovery of a process that could produce complex microelectronic devices far more cheaply, and radical advances in the operation of transistors. Working separately and unbeknownst to one another, Jack Kilby of Texas Instruments and Robert Noyce both invented what became known as the integrated circuit, a silicon chip that replaced first hundreds and then millions of transistors.

As Fairchild became the largest semiconductor company in the world, with 11,000 employees and sales of more than US$150 million per year, the culture began to change, much to the dismay of Noyce and Moore. Fairchild’s corporate headquarters in New York imposed an East Coast–type bureaucracy on the company. Noyce was being forced to assume a senior management role that he did not want or enjoy. In addition, Fairchild had not solved the quality problems that were endemic at Shockley. Years later, Grove would recall, “The research lab and the manufacturing location were seven miles apart. Those seven miles, from the standpoint of collaboration, could have been 7,000 miles.”

The critical importance of these organizational flaws began to come into focus after April 1965, when Gordon Moore presented a paper in Electronics magazine that described what others would later call Moore’s Law. Its essence was that the number of transistors that could be placed on an integrated circuit could double at regular intervals — every 18 months to two years. Moore’s Law pointed to the mind-blowing opportunity, or perhaps the inevitability, of sustained exponential growth of computer technology. To sustain the pace of progress, a company would have to combine the freewheeling open-plan creativity of Fairchild’s early years with a level of organizational discipline that had never been achieved in any company in the transistor era.

In 1968, Noyce and Moore decided to leave Fairchild. They wrote a three-page business plan, describing their intention to build one corner of the transistor business — the one focused on computer memory — into an industry. Within 48 hours they had raised $2.5 million over the phone.

A month after leaving Fairchild, Noyce and Moore established Integrated Electronics — Intel for short — in a half-abandoned 30,000-square-foot concrete building one hour south of San Francisco. At the time, big mainframe computers were storing information in crude devices called magnetic cores. Noyce wanted to replace them with tiny transistors that could store more information in much less space, accelerating the speed of the entire computer by allowing different parts to communicate more quickly. Rather than go for low margin and high volume, as Fairchild did, Intel wanted to get so far ahead of the competition that it could sell its products in high volumes for high margins. While the market was driven by America’s powerful defense establishment, Noyce and Moore also saw the rapidly growing opportunities in consumer markets.

At the time, the number of transistors that worked relative to the number produced was often well under 20 percent — an obscenely low proportion. Even making a small batch was highly complicated, a task that has been aptly compared to doing surgery on the head of a pin, in circumstances where the slightest impurity in the air or on the material would kill the patient. Workers could not eat, smoke, or even wear cosmetics on the job. Noyce and Moore had to find a tough manager who could manage this operation while overseeing an organization that would have to be preeminent in research and development, marketing, and after-sales service — all the while being ruthlessly competitive. They chose Grove, with whom they had worked closely at Fairchild.

A Surprise Choice

Grove was a surprise choice for director of operations at Intel, as he was more of a physicist than an engineer and more of a professor than a businessman. His English was heavily accented and his cumbersome hearing aid looked like it had been made behind the Iron Curtain. Nevertheless, he clearly had the necessary toughness. Whereas Noyce and Moore could articulate goals, Grove was riveted on achieving them. Noyce and Moore could explain where the train should be heading and when it should arrive; Grove had the ability and desire to get it there on time, in good condition. Over the next four decades Grove was the person most responsible for putting Moore’s Law into practice.

Whereas Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore could articulate goals, Andy Grove was riveted on achieving them.

In the early days at Fairchild, Grove, who was assistant director of research and development, had a reputation for being extremely well organized and direct, sometimes abrasive. Whereas Noyce and Moore were gracious and low-key, Grove could yell, pound the table, and intimidate anyone. But there was a deeper difference. The two bosses would give instructions and assume they would be followed. There were no penalties for ignoring them. Not so with Grove. “He imposed consequences on every employee and action in the company,” wrote journalist and historian Michael S. Malone. “And he ruthlessly enforced cost accountability on every office at Intel — Grove did not accept excuses for a failure to hit one’s numbers.”

Grove became Intel Employee Number Three. Unlike Noyce and Moore, he did not identify himself as a self-starting, job-hopping entrepreneur. “It was terrifying,” he later recalled. But Grove quickly found the secret to solving Shockley’s quality problems. He taught himself the manufacturing techniques that would dominate the computer age. It came down to shaping and inspiring a workforce that functioned and adapted smoothly and swiftly enough to keep up with the accelerating speed of the computer chip.

Andy Grove taught himself the manufacturing techniques that would dominate the computer age.

In 1969, Intel introduced its first chip, which could store 64 numbers (and was called a 64-bit DRAM, for “dynamic random-access memory”). Within a year, Intel could store 256 numbers in a chip, and within two years it could store 1,024 in a chip (called the 1103) that was smaller and more energy-efficient than its predecessor. Thanks to Grove’s relentless refining of the manufacturing process, the 1103 became the answer to the problem Intel had been created to solve — replacing the magnetic core that was the bulky memory center of the mainframe computer. Within two years, the 1103 was the biggest-selling semiconductor in the world, making Intel the largest global producer of memory semiconductors. It has maintained that status ever since.

Grove later wrote about the pathbreaking lessons he learned in these early days in his widely read book High Output Management (Random House, 1983). First, Grove wrote, every person at Intel, whether he or she worked on the manufacturing line, in the marketing office, or in the R&D lab, was responsible for attaining specific targets and was held accountable for that output. Second, output was measured by the team, and the critical role of a manager was to increase the output of his or her teams. Third, a responsible organization had to shed management layers. Supervisors and subordinates had to be in direct and constant communication. These ideas may seem commonplace today, but at the time they broke critical ground in the science and practice of management.

Early on, Grove kept a journal to record his thoughts on management. In his writings, he mused about the balance required to keep the whole of Intel inspired and ahead of its rivals. How does a manager best deal with a complex problem when a number of specialists must be involved? How fast can an organization grow and stay highly productive? Not only was he preoccupied with these fundamental issues of managing, but he was defining them clearly, debating them with colleagues, writing about them, and exploring them with students at Stanford University, where he became a part-time professor. By 1971, the year a local paper coined the term Silicon Valley, Intel was becoming a polestar of the tech industry and Grove was becoming the axis on which Intel turned.

The Cult of Management

Grove came to embrace what he called a culture of “constructive confrontation” as the best means of coaxing maximum performance out of his teams. Fiercely argumentative and well prepared, he could be brutal in challenging the less well prepared, grilling subordinates to the point of demoralizing them. Craig Barrett, Grove’s longtime Number Two and his eventual successor, later told the Washington Post, “Occasionally we…suggest [to Grove] there may be an alternative to grabbing someone and slamming them over the head with a sledgehammer.”

In 1976, Grove became chief operating officer of Intel, and in 1979 he became president as well. In these combined posts he subjected every production process and every administrative process to numerical measurement. All employees had to make exceedingly detailed budget projections, establish targets for their work, prepare constant updates, and explain discrepancies. He would ask how many functioning integrated circuits a section produced, and how long it took. How many recruits were interviewed, and what was the yield? Obsessed with cleanliness, Grove and his assistants would make surprise inspections of bathrooms, janitors’ closets, and offices, and would criticize staffers for having too many papers on their desks. Grove was the exact opposite of the leaders he saw at Fairchild Semiconductor who couldn’t translate ideas into products. He exemplified high-quality commercial output.

In 1969, the Busicom calculator company from Japan asked Intel to design specialized chips for printing, display, calculations, and other functions — for an advanced calculator. Intel responded with a proposal to build a single calculator that would include some 2,000 electronic elements. No bigger than an index card, this device packed the same computing power as had the room-sized mainframe in 1947. Then Intel struck a deal with Busicom that allowed it to keep the rights to sell the brainy chip for non-calculator applications to other customers. The new device would soon be called a microprocessor, literally, a “computer on a chip.” It would become the brains of the personal computer and many other devices that we use today, such as tablet computers and smartphones.

For the first few years, Intel and several of its rivals, including Motorola and Texas Instruments, were engaged in a fierce race to design, manufacture, and acquire customers for the new microprocessor, and Intel eventually emerged as the leader. In 1974 the company built and introduced a more advanced microprocessor, called the 8080. Intel’s edge was the organization Grove had created, which could not only design and build microprocessors with unprecedented efficiency but also provide an unmatched package of training and services to customers.

Andy Grove thought differently. He was following Moore’s Law, not the business cycle.

The 1970s ushered in the first cycles of shortages and gluts in the tech industry. Here Grove’s insights constituted another major advance in high-technology manufacturing. The cyclical downturns were devastating to the industry, and the natural response of most companies was to cut back on all spending, including R&D. Grove thought differently. He was following Moore’s Law, not the business cycle. Alone among the industry leaders, Grove responded to industry slumps by cutting budgets, cutting jobs, and forcing staff to work longer for less money. At the same time, however, he pushed Intel to become the first major company to expand R&D during downturns. This required Grove to ignore screaming shareholders — who wanted spending cuts to protect quarterly earnings — in order to come out of recessions much stronger than Intel’s rivals.

During the recession of 1974, when Grove cut staff but dramatically boosted R&D, Intel’s stock dropped 80 percent. Two years later, when the cyclical recovery came, the company’s stock quadrupled in value, from $21 per share to $88, as earnings rose 65 percent from 1975, and the payroll nearly doubled.

Facing Competition

The company saw yearly revenues grow from $9 million (with a profit of $1 million) in 1970 to $854.2 million (with a profit of $96.7 million) by the end of the decade. It was in the 1970s, too, that Intel expanded operations around the United States and the world, eventually to have facilities in several parts of California, in Oregon and Arizona, and in Malaysia. But by the end of the 1970s, Intel would start to face serious rivals for technological leadership in memory chips at home and abroad.

The domestic threat came from the Motorola 68000, which many experts decreed superior to Intel’s latest model, the 8086. Determined not to relinquish Intel’s global lead in the memory business, Grove launched Operation Crush. He mobilized the sales and marketing force, offering rich bonuses to every staffer who could keep an Intel customer — or potential customer — from choosing Motorola. After a year of trench warfare, Intel had won, preserving its lead and reputation in the field. Operation Crush “was the perfect expression of [Grove’s] conception of business as a contact sport,” said biographer Richard S. Tedlow.

Next, Intel had to cope with competition from Japan. By the early 1980s, Japanese companies were better than American ones at making memory chips; the Japanese chips had high-quality yields of 80 percent, compared with U.S. yields on the order of 50 percent. When recession hit the U.S. economy in the early 1980s, Japanese companies used their superior efficiency to lower prices and increase market share — setting off a global trade battle over the Japanese dumping of products in the United States.

Then, in one of the great turnarounds for a global company, Intel simply changed the contours of the battlefield. As the company’s profits fell from $198 million in 1984 to less than $2 million in 1985, Grove and Moore held a quiet but intense discussion about the dire situation. “If we got kicked out and the board brought in a new CEO, what do you think he would do?” Grove asked. Without hesitation, Moore replied, “He would get us out of memories” and focus on microprocessors.

Grove felt numb, but then recovered. “Why shouldn’t you and I walk out the door, come back, and do it ourselves?” That’s what they did: Grove led Intel out of memory chips and into microprocessors, a move that required firing some 8,000 people and spending more than $180 million to rebuild the company around a new core business. It was transformative leadership in its purest and most decisive form.

Years later, when Grove wrote about the shift in his second major book, Only the Paranoid Survive (Currency Doubleday, 1996), he underlined the idea of an “inflection point” — a moment, or a period of time, when a set of forces are so overwhelming that they compel a fundamental change in the rules of the game for a company or an industry. In his book, Grove admits he failed to see the Japanese challenge coming and counsels other business leaders to remain vigilant to, even paranoid about, the inevitability of such inflection points. Involving employees who are closest to the market — salespeople, middle management — can help executives understand what is happening in the minds of customers. Responding to inflection points requires an organizational structure that makes it possible for information and advice to travel quickly from the field to the top officials, but then empowers leaders to fully mobilize the company behind a chosen plan of attack. Amid all that unstructured interaction, you have to be organized, too, he explains. “Allow chaos,” he advises, “then rein it in.” When inflection points come, be ready to drop all previous assumptions and start from scratch. Open your mind to multiple sources of information and to advice that is frank, even confrontational, and possibly contrary to what you want to hear.

Golden Decade

After becoming CEO in 1987, Grove presided over a golden decade in his corporate castle. Establishing Intel as the industry standard meant that manufacturers of other computer products — software, keyboards, sound systems — had to make their products compatible with Intel’s microprocessors. The company had become a de facto monopoly with profit margins of 90 percent. In the 1990s, the PC became the gateway to the Internet, which would open a new age of communication and collaboration, afford opportunities for other upstarts to challenge incumbents, and destroy and create billions in shareholder wealth. The company prospered further.

Success did not have a calming effect on Grove, who had learned to use the fear that had stalked him since childhood to his advantage as a leader and manager, always on the watch for new inflection points. “I worry about products getting screwed up, and I worry about products getting introduced prematurely. I worry about factories not performing well, and I worry about having too many factories,” he admitted in 1996, at the pinnacle of his career.

A year earlier, Grove had encountered the most personal of inflection points: He was diagnosed with prostate cancer. He attacked it using the same approach he applied to invaders in Intel’s market. He saw quickly that medical science was divided on the best course of treatment. So over the course of eight months, he read countless books and articles and delved into the medical literature, burying himself in technical research papers. He contacted physicians from different specialties around the country. He plotted the information he gathered on charts that correlated various treatments with outcomes. Ultimately he selected high-dose radiation treatment as opposed to surgery or a number of other options. The cancer went into remission.

During Grove’s tenure at the helm, Intel’s stock market value grew from $4.3 billion to $114.7 billion, and it rose from Number 200 on the Fortune 500 list to Number 38. Sales grew from $1.9 billion to $26.3 billion, profits from $246 million to $6.1 billion. The company was doubling in size every two years. It seemed that its own growth was following Moore’s Law. Intel even became one of the leading sources of venture capital for new startups. By August 31, 2000, when its stock reached $78 per share, Intel, now valued at nearly $500 billion, had become the most valuable manufacturing company in the world, worth more than all the U.S. automakers combined. And Intel had become a truly global corporation, earning 63 percent of its revenues outside the United States. In 1990, it had operations in six other regions — Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, the West Indies, Japan, and Israel. By 2008, it would add dozens more nations, including India, China, Vietnam, and Brazil. It employed approximately 82,000 people around the world. Grove, for all his paranoia about Intel secrets, was one of the first American high-tech CEOs to establish R&D labs outside the United States.

In 1998, Grove stepped down as CEO and became chairman, pulling back from day-to-day operations to manage the board of directors. He became a sage public voice for a nation that seemed to be losing its way on management issues.

Processor at the Core

Intel stands out not only because its product sits at the core of the computer revolution but because Grove did so much to define and spread the management ideals that are now at the core of many other technology companies throughout the U.S., Europe, and Asia. Grove’s influence came equally from his business achievements, from his capacity to communicate his thoughts and experiences via his teaching and writing. He helped create a corporate culture that cultivated individualism, egalitarianism, innovation, and — miraculously in light of all that — exquisite teamwork.

Moreover, Grove defined a management process that continues to generate the production of computer chips that are ever smaller, cheaper, and more powerful. Between 1971 and 2011, Intel increased the number of transistors on a microprocessor by 1 million times. Today you can fit more than 6 million transistors into a space the size of the period at the end of this sentence. In the same time frame, the price of a transistor dropped to one-fifty-thousandth of the original. By 2013, Intel was producing 6 billion transistors per second, or 20 million per year for every person on the planet. Grove’s Intel became a symbol for our age.

Reprint No. 16212

Author profile:

-

Jeffrey E. Garten teaches courses on the global economy at the Yale School of Management, where he was formerly the dean. He has held senior positions in the Nixon, Ford, Carter, and Clinton administrations, and was a managing director at the Blackstone Group.