The urgent need for sophisticated leadership

The pandemic has highlighted a series of paradoxes inherent to the work of leaders. What comes next will depend on how well they face up to them.

A version of this article appeared in the Winter 2020 issue of strategy+business.

In the 2019 PwC Global Crisis SurveyPDF, 69 percent of respondents said they expected a global crisis in the next five years, most likely due to a financial meltdown or technology failure. Little did they know how prescient they were. Just nine months after the survey was released, an entirely different and unexpected medical and public health crisis — COVID-19 — has fundamentally altered the world. If driving change in the uncertain and turbulent environment that existed at the beginning of 2020 was a complex challenge, the degree of difficulty has now been ramped up significantly.

As we recently noted in these pages, five global forces — asymmetry of wealth, disruption, age disparities, polarization, and loss of trust — which together we’ve termed ADAPT, were already changing the way millions of people live and work. The pandemic has sharply accelerated these forces. As a result, organizations have even less time than they thought to reconfigure themselves so that they can maintain their viability in a vastly changed world. In our forthcoming book, we predict that humanity has “ten years to midnight.” But with events moving so quickly, it seems there may be even less time until the fateful hour. The good news is that by recognizing the challenges confronting society, internalizing the lessons of the pandemic, and deploying the tools and technologies at hand, we can chart a new, more adaptive course. But doing so is going to place a fresh set of demands and intense pressures on leaders.

Around the world, leaders, already stretched in all directions, have never faced so many dilemmas to navigate and contradictions to reconcile. Beyond dealing with the familiar aspects of their business, they now have to cope with the most fundamental of issues: health, well-being, safety, and financial viability. And the trade-offs are excruciating. Answers appear to conflict with each other, leading to decisions that have every likelihood of being wrong. Many companies may feel like they must return to business as normal in order for their industries, communities, and economies to survive; but the very act of returning to familiar ways of working could inhibit the ability of all these entities to succeed in the future. The speed of decision making has picked up. Decisive, or seemingly prudent, moves taken a month ago — even a week ago — can quickly become redundant, or worse, appear reckless. In a world of endless todays, medium- and long-term planning feels futile, and the scope of short-term planning is reduced to a matter of hours. Yet it is exactly in such times that people look to leaders to provide stability, hope, and a path forward. Crises like the one we’re experiencing are a crucible from which the true capabilities of leaders emerge and reputations are forged.

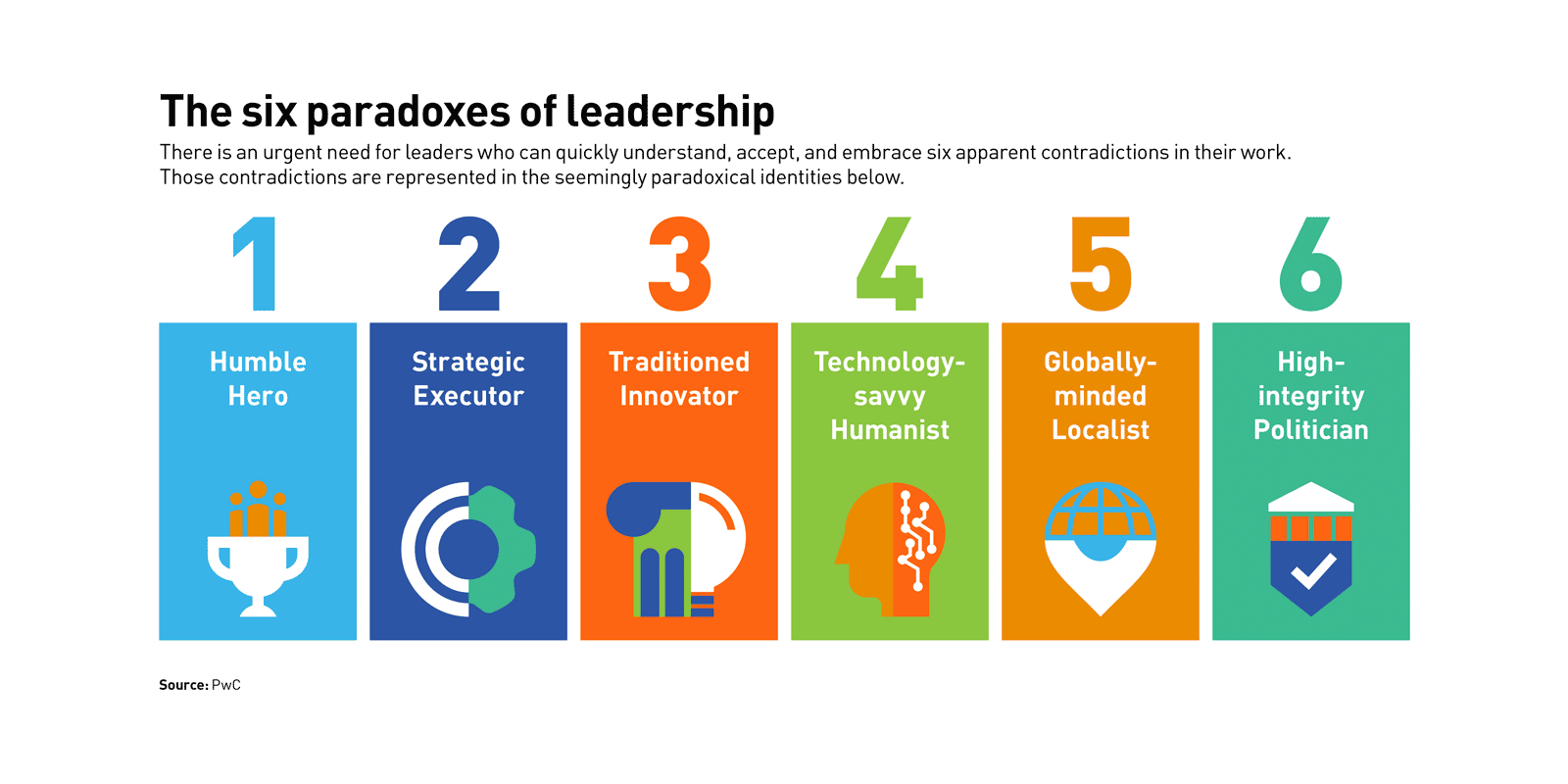

As we first noted in 2018, in our analysis of the Six paradoxes of leadership, successful leaders today must embody and negotiate a set of apparent contradictions in order to thrive in a rapidly changing world. They must have the confidence to project a clear strategy, and the humility to correct course and recognize the need for change. They must also be as adroit at surveying the landscape from 30,000 feet as they are at making sure operations function well on the ground. They must remain rooted in the traditions that made their organizations successful while continuously embracing innovation. They should consider what they need their workforce to achieve, and then effectively use enabling technology to help do it. They have to think globally while acting locally. And they must demonstrate the ability to negotiate differing viewpoints toward a consensus while maintaining their integrity. As the world seeks systematically to repair and reconfigure from the collective trauma and damage being suffered due to COVID-19 — and to prepare itself to be resilient in future crises — there is an urgent need for leaders to understand, accept, and embrace these paradoxes.

Repair: The need to act quickly and intelligently

The first step in recovery is to repair what has been broken. In order to react quickly and intelligently, leaders must have the confidence to make decisions and act in an uncertain world, and the humility to consult widely, recognize when they are wrong, and adjust course. They must be Humble Heroes, the first type of paradoxical leadership we’ll discuss.

As COVID-19 spread and community transmission took hold across the world, decisive action was required of global leaders. In China and New Zealand, Germany and South Africa, and in all corners of the world beyond, enormous pressure was placed on national leaders to act in the best interests of their countries and every one of their citizens. Each move by government was made under a harsh spotlight, at a time when little was known about how to contain or combat the virus. Acting required courage and self-belief to move decisively despite the burden of knowing that there would be a devastating cost if a wrong decision were made. In the pandemic’s early days, decisions needed to be taken with a huge amount of empathy and humility, and with a willingness to own the outcome despite the lack of a clear road forward. Through careful consultation with doctors, economists, epidemiologists, technologists, and public health experts, the potential outcomes of any of the options available would become clearer. In the face of such uncertainty, it is easy for leaders to grow overwhelmed, freeze, and struggle to make clear decisions and communicate them effectively. It is also difficult to make adjustments when conditions change.

As policies were rolled out, it was crucial for leaders to rally people to change their behaviors and take collective action. Relatively soon after the virus’s arrival in the U.S., when only one player had tested positive, Adam Silver, commissioner of the National Basketball Association, consulted with owners, players, and public health authorities — and moved quickly. The league decided on March 11 to suspend the 2019–20 season. “It was really a moment for us to step back, take a breath, ensure that everyone in the NBA community was safe and healthy and doing everything they needed to do to take care of their families,” Silver said. The move set the tone and precedent for other sports to follow (and made increasing sense given the rapid outbreak that ensued). Silver remained at all times transparent about the fact that he didn’t know if his decision was right, but that it was the best choice he had in the moment. On July 30, the NBA restarted its truncated season in Florida.

To limit and repair the damage from COVID-19, leaders had to understand the big picture — the nature of the pandemic, its global implications, the possibility of a range of outcomes — while mastering the granular details of stabilizing company operations, getting supply chains working again, and ensuring that team members were able to work remotely. In other words, they had to be really good Strategic Executors, another category of paradoxical leadership.

As COVID-19 caused societies to lock down, the impact on many businesses and sectors was immediate and devastating. CEOs had to balance the impact of their decisions on the immediate safety of their employees with the long-term consequences for the sustainability and relevance of their business. Some acted in a way that has protected their future viability, while others struggled to act quickly and damaged their organizations’ reputation in the process. In a time of crisis, it is easy to get stuck in the problems of the day, to focus on preserving existing holdings, and to do the next most obvious task to try to survive. But those who did so missed the opportunity to be agile, to position themselves for the future, or to remain connected to employees and customers who needed inspiration and hope. Equally, those who spent too much time focusing on the long term, trying to predict where the world was going and strategizing without making a move, might soon find their balance sheet in tatters and supply chains disrupted. Having failed to deal with the crisis at hand, they could face devastating consequences to their business — even if they have a crystal-clear vision for the future.

At the level of the nation-state, few leaders managed the tensions between strategy and execution as well as Jacinda Ardern, prime minister of New Zealand. After the country reported its first COVID-19 case on February 28, Ardern laid out an ambitious vision in a relatable way, encouraging all 5 million New Zealanders to be part of the response to the virus. One aspect of her strategic approach included a four-level alert system, which was implemented early in the outbreak and comprehensively and competently executed throughout its duration. On June 8, New Zealand lifted all restrictions and declared itself virus-free.

The response to the pandemic called for a great deal of improvisation on the fly — whether it was through hospitals devising new treatment protocols or companies figuring out how to develop remote adaptions of in-person services. In many instances, companies with long legacies of operational excellence were among those that were best able to quickly develop products and services to meet the new needs. And they were able to do so while maintaining their core purpose — even if their main business shut down. Time and again, we saw these Traditioned Innovators rise to the fore.

In Italy, for example, high-end seamstresses facing a sudden drop in demand for couture repurposed their capabilities to start making personal protective equipment for local hospitals. They accomplished this improvisational adjustment to meet an acute need at a time when face masks ordered from overseas were getting stuck at the borders. This pivot from the industry was impressive, as described by Claudio Marenzi, former president of the Italian textiles umbrella organization Confindustria Moda. Similarly, to deal with a sudden nationwide shortage of ventilators in the U.S., General Motors, which has a century-long tradition of engineering innovation but had never made complex medical equipment, came up with a design in a matter of weeks, worked with its supply chain, and trained employees to mass-produce thousands of the lifesaving ventilators.

These organizations relied on trust that they had already earned. They drew from that trust and, by innovating at speed and remaining true to their core, provided leadership at a time when society needed it. As we continue to grapple with the crisis, it is more important than ever for organizations to be relevant and purposeful. At the beginning of 2019, Pfizer chair and CEO Albert Bourla rolled out a new approach to R&D, which seeks to disrupt the typical ways of testing new drugs while staying focused on the company’s stated purpose of finding “breakthroughs that change patients’ lives.” The resulting ability to increase the speed with which new formulations can win FDA approvals has put the firm in a good position to drive the search for a desperately needed vaccine for COVID-19. Leaders will only be able to survive — and help reconfigure the world — if they are able to innovate in an authentic and organic way.

Rethink: Design the present with the future in mind

As organizations adjusted to new realities, technology played an important role. In many cases, technology platforms that already exerted immense influence on society saw their power, reach, and value grow rapidly. (The stocks of Amazon and Netflix were up 30 percent through the first four months of 2020, while Zoom’s has doubled.) But there are instances in which technology does not contribute equitably to society. When considering how best to leverage technology for the good of humanity, leaders must be able to bridge the gap between the raw power of tech and the needs of people — and be as fluent with emotional intelligence as they are with artificial intelligence.

Nowhere is society’s need for such Technology-savvy Humanists more obvious than in the vast education complex, which touches the lives of billions of people daily. COVID-19 has forced schools, colleges, and universities to rapidly and completely shutter their physical infrastructure, requiring that young people be educated from home. We do not yet know the consequences of this abrupt transition, but, in many cases, students have been left without the structure, discipline, and mental and emotional support they need and would otherwise find at school. Though it is possible to provide content electronically and conduct assessments virtually to test knowledge, technology alone can’t deliver the full value of an education. Without the opportunity to build relationships, encounter challenges, have robust dialogues, and learn within a pedagogical system that supports the human needs upon which educational outcomes depend, students lose a great deal. We should take care to ensure these human needs are not subjugated to those made expedient by technology.

Those educational institutions that had already integrated technology into their teaching methods were better able to manage the shift to virtual classrooms while also maintaining student collaboration and supporting continuous connection between teachers and students. And many others have stepped up during the crisis. In a recent blog post, Fiona Cottam, principal at the Hartland International School, in Dubai, described how her teachers were quickly trained on Microsoft Teams to deliver their curriculum through virtual classrooms and became experts in Twitter as a way to access resources from other educators and to establish the very human support networks they needed to deliver the best experience for pupils and their families. There has never been a more important time for leaders in education to step up and navigate the path between technology and pedagogy.

Reconfigure: Organizing for the future

As society comes to terms with the enormity of the shared experiences that the pandemic has created, we have an opportunity to shape the world in a new way. As individuals and families, we have had to learn how to be self-sufficient and resilient. Local communities have rallied to protect the vulnerable and support small businesses at risk. At the corporate level, firms have been forced to think about their workforces on a local basis, as individual countries managed the virus in different ways — and on different time lines. The disruption of global supply chains has led many businesses to reconfigure them within national borders. Leaders at all levels have been scrambling to protect their communities. In many instances, the result has been an increase in nationalism, which is accelerating the polarization and asymmetry already present in the global system. More than ever, we need leaders who understand global forces, market structures, and societal needs, and who are also capable of expressing genuine care for and understanding of their local community. We need Globally-minded Localists.

As society comes to terms with the enormity of the shared experiences that the pandemic has created, we have an opportunity to shape the world in a new way.

The most salient lesson from this virus is that it knows no borders and requires no invitation to overwhelm a country. Ultimately, nobody will be safe from infection until nearly everyone has been immunized. And the development, manufacturing, and distribution of therapeutics and vaccines will require unprecedented global cooperation. At the same time, the immense variation of cultures, behaviors, and healthcare systems around the world will require the virus to be fought and defeated at the local level.

We need leaders who can manage the tension between the need to develop solutions and protocols at the global level and the reality that they then must be implemented locally. Jack Ma, the billionaire entrepreneur and founder of the tech giant Alibaba, has been the driving force behind an ambitious operation to ship medical supplies to more than 150 countries. While following China’s diplomatic rules and ensuring his country is served first, Jack Ma has through his foundation also made a significant impact on getting essential medical equipment to where it is needed.

When the effects of the pandemic begin to settle across the world, the imperative to redesign organizations that can thrive will also present an opportunity to reconsider how they operate. Achieving a successful organizational redesign requires leaders who are sufficiently savvy to influence a broader set of stakeholders while also building essential levels of trust. In order to make changes that are both meaningful and sticky, we need a cadre of High-integrity Politicians.

Climate and sustainability are among the arenas in which ideals and politics come together. The tone of the discussion is being set by many business leaders, including Larry Fink, the CEO of asset manager BlackRock, who is resolutely incorporating climate risk into investing decisions and urging corporate leaders to reassess core assumptions about modern finance. In fact, a silver lining to the cloud cast by the coronavirus could be an increasing demand of our leaders to drive society to a more sustainable future. At a time when there is disagreement about basic facts and science, forging any sort of different path requires leadership rooted in trust. It also requires a level of inclusivity that has not often been sought in massive systemic change — an inclusivity capable of bringing in diverse and sometimes conflicting viewpoints and navigating through them so that the outcome is better than any individual proposal.

German chancellor Angela Merkel, a chemist by training, has guided her country through the worst of the pandemic and kept her reputation intact. She has successfully marshaled her scientific background and highly analytical approach to build powerful levels of trust. As a result, Germany has maintained a comparatively high level of social and economic stability while effectively combating the virus. Supported by its highly developed pharmaceutical industry, the country was able to carry out around 500,000 COVID-19 tests a week by early April; at the same time, the U.K. was only managing to test around 7,000 people. These efforts allowed Merkel to announce the easing of lockdown measures later in the month, far earlier than many other European countries.

The six paradoxes of leadership are a lot for any individual to take on. We already expect a great deal from our leaders. They must have a mastery of business, understand complex systems, and communicate effectively. And the recognition of these paradoxes adds several layers of complication to the mix. It would be incredibly rare to find someone who embodies all of them. Leaders are human, after all — flawed, complex, and prone to failure and disappointment. But because of their humanity, they are also capable of learning and evolving at great speed.

So, consider your own leadership: Where do your strengths lie? Just as important, what are your weaknesses? Are you already embodying some of these contradictions? Though not all skills are determined and developed by motivation, people tend not to pay as much attention to the areas in which they don’t possess talent, or, worse still, don’t respect those who do. To truly balance paradoxes, leaders need to learn to respect and work successfully with those who care about the things they do not.

When considering these six paradoxes, it is important to note that no single contradiction is more important than the others. In fact, they are most effective when they work in concert, as a system. And just as we may not be able to find all the elements of this kind of leadership in ourselves, we can commit to working on them. It’s important that we do so. For as difficult as COVID-19 has been, it will certainly not be the last crisis we face.

Author profiles:

- Blair Sheppard is the global leader of strategy and leadership for the PwC network. He leads a team that is responsible for articulating PwC’s global strategy across 158 countries and the development of current and next-generation PwC leaders. He is professor emeritus and dean emeritus of Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business, and is based in Durham, N.C. He tweets at @blairsheppard.

- Susannah Anfield is a member of the global strategy and leadership team at PwC. Based in London, she is a director with PwC UK.

- Alexis Jenkins and Daria Zarubina, directors in the PwC global strategy and leadership team, also contributed to this article.