A crisis of legitimacy

Today’s toughest global challenges are unintended consequences of yesterday’s success. If our prevailing institutions can’t adapt, they could lose the right to lead.

A version of this article appeared in the Autumn 2019 issue of strategy+business.

For the last 70 years the world has done remarkably well. According to the World Bank, the number of people living in extreme poverty today is less than it was in 1820, even though the world population is seven times as large. This is a truly remarkable achievement, and it goes hand in hand with equally remarkable overall advances in wealth, scientific progress, human longevity, and quality of life.

But the organizations that created these triumphs — the most prominent businesses, governments, and multilateral institutions of the post–World War II era — have failed to keep their implicit promises. As a result, today’s leading organizations face a global crisis of legitimacy. For the first time in decades, their influence, and even their right to exist, are being questioned.

Businesses are also being held accountable in new ways for the welfare, prosperity, and health of the communities around them and of the general public. PwC’s own global network of firms is among these businesses. The accusations facing any individual enterprise may or may not be justified, but the broader attitudes underlying them must be taken seriously.

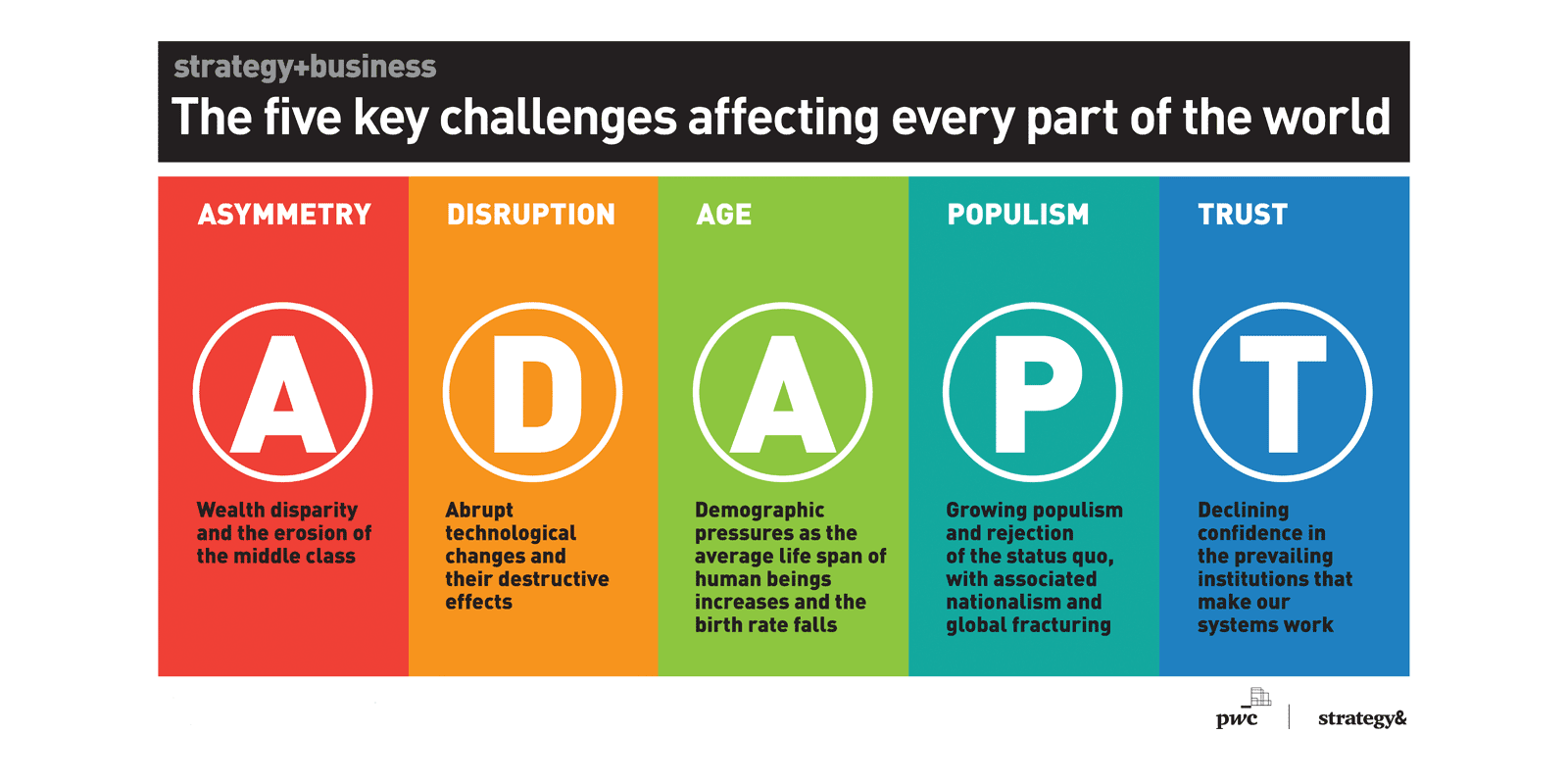

The causes of this crisis of legitimacy have to do with five basic challenges affecting every part of the world:

- Asymmetry: Wealth disparity and the erosion of the middle class

- Disruption: Abrupt technological changes and their destructive effects

- Age: Demographic pressures as the average life span of human beings increases and the birth rate falls

- Populism: Growing populism and rejection of the status quo, with associated nationalism and global fracturing

- Trust: Declining confidence in the prevailing institutions that make our systems work.

(We use the acronym ADAPT to list these challenges because it evokes the inherent change in our time and the need for institutions to respond with new attitudes and behaviors.)

A few other challenges, such as climate change and human rights issues, may occur to you as equally important. They are not included in this list because they are not at the forefront of this particular crisis of legitimacy in the same way. But they are affected by it; if leading businesses and global institutions lose their perceived value, it will be harder to address every other issue affecting the world today.

Ignoring the crisis of legitimacy is not an option — not even for business leaders who feel their primary responsibility is to their shareholders. If we postpone solutions too long, we could go past the point of no return: The cost of solving these problems will be too high. Brexit could be a test case. The costs and difficulties of withdrawal could be echoed in other political breakdowns around the world. And if you don’t believe that widespread economic and political disruption is possible right now, then consider the other revolutions and abrupt, dramatic changes in sovereignty that have occurred in the last 250 years, often with technological shifts and widespread dissatisfaction as key factors.

What, then, would it take to rebuild the credibility of the important businesses of the world (and other critical multilateral institutions) so that they retain enough legitimacy to not just survive, but participate as leaders in solving the world’s urgent problems? As business leaders, we must accept our responsibility for helping to solve these problems. We must recognize that the solutions are neither easy nor obvious, and that they will require a fundamental shift in thinking. We need to recognize the factors that generated the problems, how they emerged as the unintended consequences of successful business and political practices, why they have been ignored for so long, and how to come to terms with addressing them.

Asymmetry: Prosperity derailed

The city of Hamilton, Ontario, gained its prosperity from steel mills. Opened in the early 1900s, they were a constant source of good wages for industrial workers who could afford small houses nearby, and who expected their children to attend college and live better lives than they had. Hamilton’s two global steelmaking companies, Stelco and Dofasco, supported a vibrant community with a major university (McMaster) and a renowned medical school.

If you don’t believe that widespread economic and political disruption is possible right now, then consider the revolutions that have occurred in the last 250 years.

But after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1990, Canada’s steel industry collapsed. Mill workers had trouble finding new jobs, and the work they found was often lower paid. Their neighborhoods have since become less desirable, their children’s prospects bleaker. However, today, entrepreneurs in higher-tech industries in Hamilton are doing better than ever, and the area’s wine region is thriving.

Hamilton is a microcosm of the economic challenges facing us — not just in industrialized countries such as Canada, but everywhere. Wealth disparity is increasing; the world’s assets are now concentrated in the hands of a small number of people. As the gap widens, the average wealth and purchasing power of the middle class erodes. This may be more obvious in the OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries, where the size of middle-income groups (those with a household net income that is between 0.75 and two times the median) has consistently decreased since 1988. But it is also true of major emerging economies such as China and India, where the urban middle class has not kept pace with those at the top of the pyramid, and is even at risk of slipping back. (According to the crowdsourced cost-of-living database Numbeo, a number of cities in emerging economies have extremely high ratios of average housing price to average annual income. These include Algiers, Beijing, Caracas, Guangzhou, Kathmandu, Mumbai, Phnom Penh, Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Tehran.) In the world as a whole, less than 1 percent of the adults hold more than 45 percent of the wealth; between 2008 and 2018, the number of billionaires more than doubled, from 1,125 to 2,754.

Two main factors have driven economic asymmetry: the shift of work from high-wage to lower-wage countries (due to globalization and automation) and the growing amount of wealth, including that generated by productivity gains, captured by shareholders instead of employees. Both factors have had a host of secondary effects, often showing up as disparities between capital holders and wage earners. Analysis by the International Labour Organization (pdf) has found that in 52 high-income countries, average labor productivity (and thus typically profits) grew nearly 17 percent from 1999 to 2015, while real wages grew only about 13 percent.

Over time, wealthy investors have used their leverage to widen the gap still further. For instance, they have moved away from the public capital markets to private equity, hedge funds, and syndicates. These vehicles tend to give better returns, but are open only to accredited investors. Meanwhile, the prevailing shift in pension funds — from defined-benefit schemes, which feature a monthly payment, to defined-contribution systems, in which employees accrue a lump sum to live on after retirement — has left many middle-class people dependent on the stock market for their old age, which is less advantaged and thus less capable of supporting them.

Other effects of asymmetry reinforce the trend, exacerbating the damage it does. For example, rising house prices will prevent many middle-class people currently under the age of 40 from buying homes in their lifetime. They will thus lose one of the main middle-class means of accumulating wealth. In Australia, according to theconversation.com (a site that reports on academic research), homeownership by 25- to 34-year-olds fell from 61 percent to 44 percent between 1981 and 2016.

Wealth disparity also challenges the ability of many governments to collect tax revenues and provide services. The three most widely used forms of individual taxation are disproportionately low for those with extreme wealth; they receive less of their wealth in salaries (income tax), consume relatively little in proportion to their wealth (consumption tax), and often live in residences owned by corporations (real estate tax). In addition, in recent years, technological advances have made it easier for high-net-worth individuals to move their money to low-tax regimes. Thus, as wealth disparity grows, the availability of tax revenue shrinks, just when more is needed.

Finally, economic asymmetry makes the middle class more vulnerable to other threats. If automation takes middle-class workers’ jobs away, they have less of a cushion to fall back on while looking for work or developing new skills. If storms and other extreme weather events related to climate change threaten their homes and livelihoods, they are less likely to have insurance, and more likely to lose any savings they have. People also become more vulnerable to emotional problems. When quality of life for the middle class declines in a seemingly never-ending cycle, people respond by losing hope. In the rural U.S. in the last few years, for example, rates of excessive drinking, drug overdoses, and suicide have increased enough to shorten average life expectancy in the United States.

Although much has been written about the effects of asymmetry, it does not receive the attention it deserves among global business leaders. That’s in part because of the way economic success is most often measured: through shareholder value for organizations and GDP for countries. Reliance on these two metrics has distorted our understanding of economic value; they provide high-level views of average prosperity gains that mask the disparities beneath.

Disruption: Technology unbound

A few years ago, one of the remarkable success stories of China was the midsized city of Kunshan, just outside Shanghai. As recently as the late 1970s, many of its people had lived in huts, subsisting on the land or lakes. Then it became a manufacturing center known as Little Taiwan. Its factories attracted many workers from central and western China, typically women chosen for their skill at small-parts assembly. They lived in large communal housing and sent much of their salary home.

Kunshan ultimately developed one of the world’s great universities and is launching many technology-based startups. It is now a thriving, modern city with many cultural activities, high-quality infrastructure, trees and flowers everywhere, and a reputation as a foodie town. But it is no longer a magnet for factory employees; its plants are converting to robots. This leaves many of Kunshan’s migrant employees with few options beyond returning home to an existence similar to the one they left behind.

The impact of technological disruption is just now becoming apparent. To be sure, it does have an extremely positive side. Advances in medicine, materials science, energy production, and information technology have improved life in ways that might have been unimaginable in the early 1900s. Entrepreneurs have abandoned old business models to create powerful startups that generate great wealth and prosperity, and improve the quality of life.

But disruption is also having severe effects — on workers, who face potential job losses from automation; on governments, which have to manage many new stresses; and especially on existing businesses. According to Credit Suisse, the average life span of a Standard & Poor’s company has decreased since the 1950s, from more than 60 years then to less than 20 years today. “[Disruption in itself] is nothing new,” noted the bank’s 2018 report on this theme. What’s new is “the speed, complexity, and global nature of it.”

Most industries are adapting; business leaders know they have to embrace new forms of digital technology, and new platforms are emerging to help them do this. Solutions are being found for the challenges of artificial intelligence (AI), automation, cyber-attack, intellectual property theft, and the misuse of consumer data. Nonetheless, these problems are so pervasive and daunting that many mainstream institutions still find them hard to manage, which has exacerbated the loss of their credibility.

The worst effects are felt by established institutions whose reputations depend to some degree on public trust: banks and financial-services firms, the media, regulators, schools, the legal system, and the police. These institutions have generally been in existence for a long time, and they were designed to change slowly — to be solid, reliable entities that could provide a sustained service to society. Professional journalists, long supported by stable media funded through advertising and subscriptions, are replaced by “clickbait vendors” on social media platforms, who attract attention by telling people what they want to hear. Education must keep up with the demands for new skills and major changes in the way people receive information. Police are grappling with the task of preventing new forms of crime, while also having their own actions captured on video and distributed digitally. Regulators and tax authorities are trying to catch up with radical new businesses that operate across a broad range of countries and industries.

To address the impact of technological disruption, we will need to invest far more money, time, attention, and knowledge in building the skills of the global workforce. This will involve identifying the capabilities that companies and governments need, and creating a culture of lifelong learning, including for people who have not been used to it. In many cases, this challenge will bring together government, industry, and academic groups that have not worked together before. The challenge of re-skilling the planet is immense, but the stakes could not be higher; without the right talent, the world’s institutions will simply not be able to fulfill their purpose.

Age: Demographics unresolved

At Japan’s Ministry of Education, senior officials tell a tale of woe: shrinking enrollment, competition for revenues from a declining tax base, and a lack of jobs for teachers and university professors. The average age in Japan will be 53 in 2050, a function of declining fertility rates and increasing average life expectancy. Unless there is a significant unforeseen change, the country can look ahead to overtaxed healthcare systems, inadequate pensions and retirement savings, and a relatively small workforce supporting a huge base of retirees.

Then there’s India’s Ministry of Education. It’s hard to believe it exists in the same world as Japan’s. Indian officials have proposed building 500,000 new schools over the next decade, including at least 1,000 new universities, to accommodate the country’s burgeoning youthful population. But they’ll never get the approval; the task would consume several times the government’s entire budget. Instead, the country will try to create between 10 million and 18 million new jobs a year at a time when many of its newly formed technology jobs, such as call center staffing, are being threatened by technological disruption and AI.

Most countries today fall into one of two groups, defined by their demographic problems. Old-population societies such as Japan, China, Russia, and most Western European countries have too many aging people to sustain current workforce policies and pension systems. Their challenges are exacerbated by the medical and lifestyle-related challenges of a longer life. Even the healthiest people over 65 require higher levels of medical expenditure, and increases in chronic disease and lifelong obesity add dramatically to these costs. It’s not surprising that healthcare expenses per capita are rising at alarming rates throughout the developed world.

On the opposite end of the spectrum are young-population societies: India, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, Thailand, most of Africa, much of Latin America, and many other emerging economies. If they don’t each generate at least hundreds of thousands of jobs per year for the next 10 years, they will face an immense population of unrooted, unsupported people. Most of these countries already have difficulties providing education and jobs for their young citizens, and the challenge will get even more difficult as companies adopt automated manufacturing systems embedded with AI. These countries won’t be able to jump-start their manufacturing industries as South Korea and China did, with low-wage factory jobs, because those jobs will be replaced by robots.

The tension raised by these soaring old and young populations can be summed up in a metric known as the age dependency ratio. This is the percentage of people who cannot work and thus need economic support. The figure is already almost double what it was in 1950, and is rising at an unprecedented rate (see “Global age dependency ratio, 1950–2050”).

These demographic issues are even more daunting when added to the negative consequences of asymmetry and disruption. There is no clear view of how to design or fund an effective response, and few institutions are confronting them with the requisite speed and creativity. Older countries may soon lose their capacity to support themselves and young countries will probably be overwhelmed by people looking for any way to make a living.

Populism: Consensus fractured

The week before the Brexit vote in May 2016, a Liverpool taxi driver told his U.S. passenger that he was voting to leave the European Union. He had grown up in Liverpool, he said, but he no longer recognized the town. Two of his friends had given up their fishing business because of the catch limits imposed by the E.U.; violent crime was increasing; the pubs and restaurants he liked were closing. He blamed all these shifts on decisions made in Brussels. His life was being changed, he said, by people he did not know, whom he could not influence, and who felt no accountability toward him.

“My Brexit vote is the most important decision of my life,” he said, adding that he’d studied the issue for a year. Then he summed up his opposition to the E.U.: “It’s taxation and regulation without representation. You started a revolution over this in America, did you not?”

When asked if he recognized the economic consequences of an exit, he mused, “Will it be worse than the Second World War? We survived that one.”

The populist movement around the world is fueled by attitudes like this. It should not be understood as allegiance to authoritarianism. It is a basic combination of fear of future uncertainty and concerns about fairness. When wages are stagnant for years, the quality of life is poorer, and the future is uncertain, anxiety grows in the middle class. People naturally experience their status and relevance as diminished — and they worry that their children will be even worse off. When the accumulation of great wealth in the hands of a few is conspicuous, people perceive a basic lack of fairness in society; they believe that institutions and political leaders are biased against them. When uncertainty and unfairness are perceived as the overarching state of affairs, people tend to vote more for populists and nationalists. These political candidates seem to be the only ones who hear them as they want to be heard.

Populist movements can lead politicians to support policies that, often unintentionally, have a chaotic effect on business — for example, they may involve retreating from global agreements, governance structures, and standards. Investment and innovation, which rely on the free flow of ideas, goods, and people across boundaries, are more difficult in the kind of closed-border world favored by populism. Protectionist tariffs make it more difficult for businesses to compete. And populism makes it increasingly difficult for global enterprises to defend (or continue) the international supply chain operations that have sustained them for decades.

The nationalist challenge has placed a burden of proof on global institutions to show that they are capable of answering the genuine demands that people have for a visibly better future, no matter where they are located or what kind of work they do. This will require sustainable solutions for several significant issues, such as the growing number of weather-related disasters, the emotionally charged issue of immigration policy, and the challenge of skill building. Solutions must come first — only when fundamental issues are credibly understood and addressed will trust in society’s institutions return.

We no longer live in a world in which movement toward liberal democracy and capitalism can be taken for granted. It is doubtful that the world will return to a relatively simple global multilateral order; there will be several competing political and economic models, each dominant in a few regions. The most influential large nations will have different views on how to compete economically, on who should write the rules (as in trade, climate, and financial regulation), on how to share resources, and on how to organize the interoperable platforms of digitally driven commerce. The models may vary widely, but they will also need to function effectively alongside one another. The smaller countries will try to preserve their independence while navigating between these larger powers. In the end, the competition of ideas brought on by populism may be a blessing in disguise. The older models are no longer perceived as advancing the common good, and with luck, new models will emerge that do a better job.

Trust: Institutions disrespected

In November 2018, when the Group of 20 international forum (G20) held its annual summit in Buenos Aires, Argentina, a corruption scandal was dominating local headlines. Former Argentine president Cristina Kirchner had been formally accused of being one of the leaders of a massive bribery network, which included many of the country’s business leaders. A raft of similar cases had recently come to light, starting in Brazil and moving throughout Latin America, highlighted by a wave of media attention and facilitated by reforms in the criminal justice system. The revelations were generally treated as damaging, but not surprising; commentators warned of indifference and “scandal fatigue.” The average citizen in the region has long regarded corruption as a way of life, feels little trust in government or other related institutions, and assumes that no sustainable solution is likely.

Latin America is not unique. At a time of electronic media saturation and partisan political rancor, when email hacks and political leaks occur regularly, mistrust of institutions has become a worldwide phenomenon. This has taken more of a toll than people realize. The Edelman Trust Barometer, which has tracked the perception of institutional credibility since 2001, presents a sobering picture. In 2019, the firm found a record-high trust gap between the “informed public” and everyone else. The first group (college-educated people age 25 to 64, in the top quarter of household income in their market) reported significant engagement with news media and tended to have a positive view of society’s institutions. The rest of the population, in aggregate, was far more skeptical. Overall, only about 20 percent of the entire global population said they felt the system was working for them.

Institutions that have lost credibility are government, corporations, media, schools and universities, and religious organizations. Worse still, a significant amount of the loss of trust reflects institutional bad behavior: The 2008 financial crisis, institutional leaks, and a wide range of public disclosures of egregious acts have all contributed. The net result is a broad body of people who do not trust any institution charged with shepherding their future. Consider, for example, France’s yellow vest protests, which began in opposition to a green fuel tax in the fall of 2018. No solution was considered sufficient because no one was trusted to deliver results. Without some trustworthy institutions, civilization cannot fully function.

The sources of disruption themselves, technology and social media, are also increasingly seen as untrustworthy. People are becoming preoccupied with privacy and security. They see their personal data being stolen from sites they thought were secure, learn of the manipulation of people through social media, and find out about algorithms that facilitate the purchase of bomb materials without traceability, as occurred in recent terrorist attacks in the United Kingdom.

It’s difficult to see how trust can be broadly restored, but data from the Edelman barometer offers some clues. Globally, 75 percent of respondents trusted the enterprise they worked for — a much higher figure than that for trust in media (47 percent), government (48 percent), business in general (56 percent), or nongovernmental organizations (57 percent). Many of these respondents said they look to business as a catalyst for social change; 71 percent agreed, for example, that “it’s critically important for my CEO to respond to challenging times.”

To regain trust, institutions have to be seen as functionally competent and as working for the common good. Schools, businesses, and governments are gradually learning what this means: It means not just providing value to everyone who interacts with them, but doing so in an engaging way, so that the experience of interacting with them is welcome. Many efforts to do this in the past have been simplistic or insincere; this time, the stakes are high, and halfhearted efforts will not suffice. The lack of trust in organizations today is a sign that full-scale renewal is needed, as is a shift to a broader sense of purpose.

A catalyst for change

If leaders are serious about restoring trust in mainstream institutions, they have to think freshly about legitimacy and leverage. Many institutions’ day-to-day practices and ways of thinking have contributed to this crisis. Building trust requires changing habitual practices, often at a large scale. What are the fresh ideas for effectively addressing 21st-century challenges? We think these are the places to start:

• Take responsibility. The issues described here are vast, and it’s easy to become inured to them, but business leaders have to care about the results. We need to create alternatives to a system that sets up new college graduates with massive personal debt and little opportunity; that lets people retire broke with almost no safety net; and that lets people in midcareer lose their jobs to automation and with them their homes and hope for their children’s future. We have to care about the middle class around the world, to prevent it from being hollowed out. We have to balance that with care about the poorest regions, the regions at risk of drought, flooding, and neglect. If we don’t want these results funded in the long run by wealth redistribution, we have to foster them in the short run through genuine commitment, more effective management, and smarter solutions.

• Move with rapid speed and at massive scale. Recognize the urgency and scope of the issues we must address; we cannot take up time debating and conferring before acting. For example, finding education and work for 442 million people in Africa over the next 10 years cannot be accomplished at the current pace of existing multinational institutions.

• Be local first. In democratic systems, international and national policy debates have become so polarized that we are unlikely to find the answers we need there. Nor can we fully trust authoritarian systems, which have their own agendas. During the next few years, the most important role of international societies and national governments may be to step back and create the conditions that will allow local communities to thrive by solving problems. They need to be set up to experiment, pay attention to the results, offer transparency, and learn from their own experience and one another. There is a better chance to build social cohesion and inclusive opportunity at the level of local communities — if we can deploy our growing expertise to support them.

• Redefine success. The prevailing economic focus on GDP growth and shareholder value has hidden the real harms people are experiencing. National and global averages do not paint a full picture. Organizations must make decisions based on their more fundamental purpose: to improve the world’s value in human as well as economic terms. They need to be held accountable to the success of the communities in which they operate. Countries need to refocus on overall societal well-being and not just GDP growth.

• Humanize technology. Digital tools and media are, unless programmed otherwise, indifferent to their consequences. It is up to people to ensure the effects are beneficial. Social media can produce accurate news. Technology can improve memory and attention and reduce depression and anxiety. AI can replicate the best of us, not the worst of us. To ensure this happens, we need more people to be digitally skilled and aware, capable of driving better outcomes and more inclusive innovation.

• Reinvent our institutions. Tax systems can be made fairer. Capital markets can be made more accessible and effective. Educational systems can be brought up to date, in both their methods and their curricula, to instill the skills society needs. We must engage our imagination to find new models of organizational practice and governance. Most of these new models involve new levels of transparency. Egregious practices, which once seemed like they could be hidden, will now be more likely to come to light.

• Rethink leadership. Perhaps most importantly, we need to recognize the inherent paradoxes that leaders must navigate today: to be technologically savvy and acutely focused on furthering humanity; to heroically drive change but remain humble enough to recognize our limits; to have the political skills to operate among diverse constituencies, but not lose our integrity; to prize that which came before and still drive massive innovation. Those who are followers — members of businesses, organizations, and society — should expect no less of their leaders. Everyone should recognize that at some moment in the near future, each person will be called upon to lead in some small way.

These may seem like daunting or quixotic goals. But they are achievable. Indeed, many of them have matured in recent years, away from earlier idealism and optimism, and toward more pragmatic understanding. But that, too, is reason for hope. We don’t know, right now, what solutions will work best for the crisis of legitimacy. But we know that there will be great opportunities, along with daunting challenges, involved in finding out.

Author profiles:

- Blair Sheppard is the global leader of strategy and leadership development for the PwC network of companies. He is also professor emeritus and dean emeritus of Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business. He is based in Durham, N.C.

- Ceri-Ann Droog is a thought leader in global strategy and leadership development. Based in London, she is a director with PwC UK.

- Also contributing to this article were directors in global strategy and leadership development Thomas Minet (PwC US) and Daria Zarubina (PwC Russia).