Tom Frieden’s plan for public — and economic — health

The former director of the CDC and current head of Resolve to Save Lives explains why economic recovery will only arrive when the coronavirus is under control.

Dr. Thomas Frieden has spearheaded efforts to improve public health for more than three decades. Few executives have more experience in leading large public health bureaucracies as they confront epidemics. After earning degrees in medicine and public health from Columbia University, he served as assistant commissioner of health and director of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Bureau of Tuberculosis Control, where his effort to combat multidrug-resistant tuberculosis became an international model. As health commissioner for New York City from 2002 to 2009, he implemented many of then mayor Michael Bloomberg’s far-reaching efforts to reduce smoking and combat diabetes and obesity. At the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which he directed from 2009 to 2017, he managed the successful response to the 2014 Ebola outbreak. Since 2017, Frieden has run Resolve to Save Lives, a nonprofit backed by philanthropists including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Bloomberg Philanthropies that aims to save 100 million lives by fighting cardiovascular disease and epidemics. In an interview with strategy+business editor-in-chief Daniel Gross, Frieden discussed effective strategies for combating the virus and how all leaders can adapt some best practices from epidemiology to make their operations more resilient to unexpected threats.

S+B: Epidemiology has really come to the fore in the past few months, as it has become evident that our global systems can’t run effectively in the age of coronavirus. It strikes me that epidemiologists have a lot to teach people who are leading organizations — not just how to think about COVID-19, but also how to think about other systemic and viral types of problems that can infect their networks and ecosystems. What are the components of an effective public health strategy?

FRIEDEN: My overall concept of how to get things done in public health has the shorthand of TOP: technical, operational, political. You really need to have the technical rigor to know that if you do what you’re trying to do, you’re going to get the results you want to get. For that, there needs to be a fairly sophisticated data analytic framework. You’ll see a lot of comments in the papers and a lot of talk on television from people who have public health degrees and who may even have degrees in epidemiology. But we have to rely on experienced professionals and experts. You wouldn’t go to a surgeon who has never done the operation before. And you shouldn’t be taking outbreak advice from someone who hasn’t controlled multiple outbreaks before. We have to beware of amateur epidemiology.

The O in TOP is operational excellence. The public sector doesn’t have an outcomes-based feedback loop; it has a political feedback loop or an organizational feedback loop. You don’t want to be in a position where you keep trying to sell a product that nobody buys. I’m a tuberculosis doctor, and tuberculosis has the best management information system of any public health program in the world. That kind of rigor is what I try to put into all of the work that I do. My first big management job was as head of tuberculosis [TB] control for New York City [in the early 1990s], in the midst of a terrible outbreak of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. And we got the money from the city, state, and federal government, but the city’s administrative procedures were abysmal. And it was taking forever to bring staff on board, and staff are essential.

I was trained as an epidemiologist by the CDC at the Epidemic Intelligence Service program. But I realized that I didn’t know much about hiring or management. I was 31 years old. It was considered the biggest public health crisis in the U.S. at the time. The head of TB for the national program told me it was hopeless. We weren’t going to be able to fix it for another 10 or 15 years. I took that as a challenge. But I had to hire hundreds of staff quickly. I set up a surveillance system for our hiring process. [In public health, surveillance means the ongoing systematic collection, analysis, and use of information and the dissemination of that information to those who need to know.] There were 27 steps it took to hire someone. And then I calculated the median dwell time of each of those 27 steps. And I provided that on a weekly basis to my boss, New York City health commissioner Peggy Hamburg, and we worked with her chief administrator to knock down those 27 barriers one by one.

S+B: Though the technical and operational elements are under the control of a public health leader, it seems like the P — the political element — is not. Is that the hardest component to deal with?

FRIEDEN: The political scientist James Q. Wilson was a colleague of my brother, who also taught at UCLA at the time. And he advised me that you need people outside the government to push you to do things that need to be done and that you want to do. Otherwise, it either won’t happen or won’t be sustained. That was extremely wise advice, because the public sector does need civil society pushing things. In our philanthropic efforts now, we work to strengthen the public sector and strengthen civil society, and establish a monitoring system that measures progress. It’s very important. Because if you’re not making progress, you have to course correct. And if you are making progress, you need to prove it and defend it.

S+B: If you talk to people who run businesses, they will tell you that data — often about their customers — is the most valuable resource. What role does data management play in epidemiology?

FRIEDEN: The hallmark of a good public health program is the effective use of data. When it comes to an outbreak response or an epidemic response, a good public health program uses data to improve performance. A great public health program uses data in real time to improve performance. We think of data not just as numbers, though. In public health, we see the faces and the lives behind the numbers. I cry when I see that more than 400 healthcare workers in the U.S. have died of COVID-19. It’s outrageous. It’s just outrageous.

Models are not of the most value to predict the future. Models are important to change the future. And the best use of a model is to guide action. Not to guess in some ghoulish way how many people are going to die, but to prevent people from dying.”

My favorite story about the real-time use of data is from the tobacco cessation program we did when I was health commissioner of New York City. We ran a promotion on 311 [the city government information line]; any smoker could call in and get a course of over-the-counter nicotine patches and/or nicotine gum sent to them. We basically trained 311 operators to be legal pharmaceutical dispensers. And we had the data uploaded every day of what zip codes the calls were coming from. We also had a survey that told us how many smokers were in every zip code. So every night we saw which zip codes were calling and which zip codes weren’t. And we sent college kids out to poster those that weren’t to ramp up on our calls.

Another example of that is, in the midst of Ebola in Guinea, one of the great epidemiologists at CDC, Kim Lindblade, did a study we call the quick-and-dirty study. It showed that the contacts of Ebola patients who had died were vastly more likely to get Ebola than the contacts of Ebola patients who had not died. Intuitively, you might think, “Well, of course that’s the case.” But it wasn’t known before. And it had immediate implications. It meant you had to put significantly more attention into finding those contacts.

S+B: One of the thorniest issues relating to COVID-19 has been the interplay between health and the economy, and the trade-offs that are made. It seems that epidemiologists have a different view than many economists do.

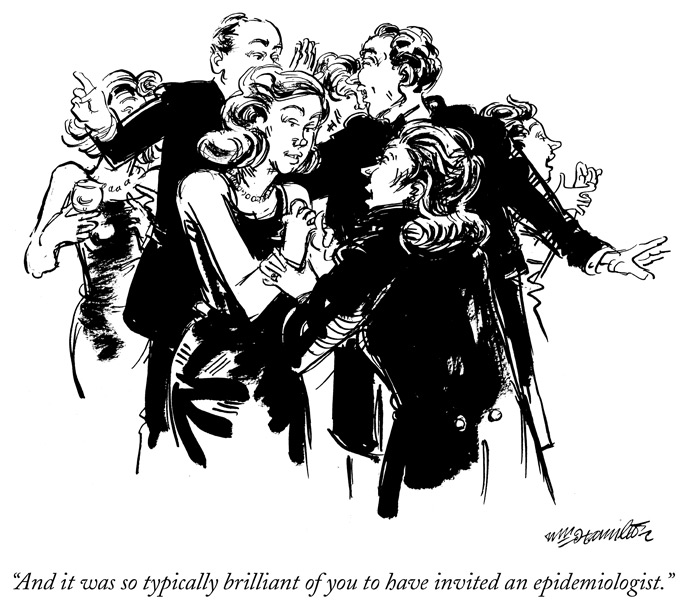

FRIEDEN: I remember a New Yorker cartoon from several years ago, an Upper West Side of Manhattan party scene, and one person says to the other, “and it was so typically brilliant of you to have invited an epidemiologist.” This is a moment for listening to epidemiologists. Public health is about maximizing health. It’s about the organized efforts of society to improve how healthy and productive, how functional people’s lives are, and how long people live. And it is a route to economic progress. Think about safe water and better nutrition, which drove health improvements in the first half of the 20th century in the U.S. and many other countries, and enabled massive economic growth. In the current environment, people think, “Oh, we have to open our economy, and COVID is forcing it closed.” It’s a total misconception. Yogi Berra said, “If people don’t want to come out to the ballpark, how are you going to force them?” If we open things, it’s not going to work if people are not comfortable coming out.

If people don’t feel safe, they’re not going to participate economically. So public health is not the barrier to economic recovery. Public health is the road to economic recovery. We’ve seen that around the world, countries, provinces, and states that have been guided by public health and that have fully supported public health have done better. They’ve had fewer deaths, less disease, and less economic devastation.

S+B: You’ve said that an epidemiologist looks at things a little differently from other professionals. What do you mean by that?

FRIEDEN: Basically, we don’t look at healthcare in terms of how many visits there were or even how much spending there is. But rather, we ask: “How many lives are you saving?” Many years ago, as New York City health commissioner, I helped to create the largest electronic health record project in the United States. And I asked a colleague: “Now that we’re putting these health records together, how do we save the most lives with healthcare?” And I looked in a database that has more than 10 million articles, and not one of them could answer that question. It turns out, the answer is focusing on cardiovascular disease prevention, particularly hypertension. If you go to any hospital or healthcare system in the U.S., and you ask how do you save the most lives, you’ll have very, very few people give you the right answer.

S+B: That question of how many lives you’re saving has a new sense of urgency now that we are coping with COVID-19. What concerns you about the response that we’ve seen thus far?

FRIEDEN: I think I would just say that in terms of COVID, one of the things that’s alarming is that we’re not really using the right data in real time, in the U.S. as a whole, to adapt our response. When we learn more, we do better. When we change our policies, that’s frequently not because it was wrong before, but because we’ve learned better how to do it. The misunderstanding of models has been just horrifying to watch. Models are not of the most value when they’re used to predict the future. Models are important to change the future. And the best use of a model is to guide action — not to guess in some ghoulish way how many people are going to die, but to prevent people from dying.

I think we’ve seen a bunch of false dichotomies when it comes to COVID. It’s not open versus closed. We were never fully closed, and we’re not going to be fully open until we have a safe, effective, and universal vaccine, which, by the way, is going to take a long time and not be simple. Second, it’s not health versus economics. Health is the route to economic recovery. Third, it’s not mask versus no mask. It’s when and where and how we mask. And it’s not, oh, this is either overblown or it’s the worst pandemic in history. It’s a pandemic that you have to understand for different groups. For kids under 20, it’s similar to a flu season. For people over 60 or with underlying health conditions, it’s like the 1918 pandemic.

S+B: What does your experience tell you about an effective public health response?

FRIEDEN: What the public sector has to do is to box the virus in. And there’s a four-part strategy to box it in: testing, isolation, contact tracing, quarantine. If we do those four things, we can put the virus into less and less space, so we have more space in society to come out. Each of those four is a longer conversation. Testing is not about numbers. It’s about testing the right people at the right time and doing the right thing with the results. Isolation means protecting our healthcare workers, nursing home residents; protecting people in jails, prisons, meatpacking factories; and protecting families of people who are infected. The countries that do the best in the world pull people out of the household, preferably voluntarily, because otherwise you have another generation of spread. And then contact tracing, which is not very well understood. This isn’t going to be an app or a bunch of people in a call center. It’s a service. It’s a service that builds a human bond with individual patients who are sick, gains their trust, addresses their needs, and then helps them to help us warn contacts.

S+B: A lot of leaders of companies are suddenly having to communicate a great deal with employees and stakeholders about the health implications of COVID-19. What is your advice to people who lead organizations who do not have the background in epidemiology on how to talk about the pandemic?

FRIEDEN: First, the most important way you can make your workers safer and protect your business is to make sure that public health response in your community is good. Because otherwise, it’s like being in a hurricane — having a single umbrella is not going to help. You need to have control in the community, or you will have cases in your workplace. Second, don’t think of the best response as being one thing, like lots of testing. It needs to be a comprehensive response. And third, recognize that this is going to take a while. So think of ways that your business can support people in quarantine. Think of ways you could advocate for public health, so they get the political support and the resources they need to succeed.

S+B: The comparison between computer viruses and human viruses goes only so far. But are there modes of thinking or principles of epidemiology well suited to inform people who run businesses and organizations as they go through their day?

FRIEDEN: Well, there’s a specific and a general response here. The specific is for things like computer viruses. You wouldn’t call it epidemiology, but you can use some of the same tools of human epidemiology to analyze the spread of computer viruses. But the more general rule has to do with the importance of getting data analysis right. And with big data, I think people are recognizing that we are not replacing people with computers. What’s really needed is incisive analysis.

A really good data analyst is someone who understands how to use the data. I’ll paraphrase Karl Marx, who said historians have heretofore interpreted the world in different ways. The job, however, is to change it. The same is true for epidemiology. There are epidemiologists who describe the world, but the specific brand of epidemiology that the CDC is so good at I refer to as interventional epidemiology. The Epidemic Intelligence Service of CDC really teaches people how to use data to change disease. How do you use that data in real time? And we’ve learned from the app development world about the efficacy of doing A/B tests in real time. So if you’re using really good analysis to improve your data, and then you’re figuring out a way to get that data in real time, you’re really set up for success.