Draw yourself a leader

Visual thinking can give you fresh insight into your own beliefs about leadership.

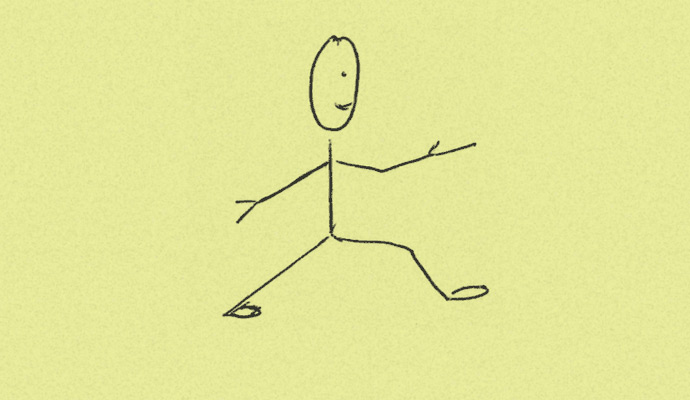

Before you read any more of this column, grab a piece of paper and a pen or pencil. Now draw a leader. Don’t think too hard or worry about getting it “right.” Don’t fret about your artistic ability. Just sketch out what comes to mind.

Once you are done, take a good look at your work. Did you draw yourself? A lone figure? A group? Did you even draw a figure at all?

We’ll return to these drawings soon, but first, some background: This is an exercise that came to me after a conversation I had with the CEO of the Asia-Pacific region for a large global technology firm. I asked her the broad question of how she thinks of leadership. She came back with a drawing.

The CEO told me that she always draws herself at the center of a network of nodes rather than at the top of a hierarchy. It’s a depiction that represents her role as a connector and allocator of resources and talent, she said. Her work doesn’t involve a lot of top-down orders. Instead, when she leads, she strives to create the conditions in which innovation and robust customer relationships thrive. That requires being inside the hub of activity, not above it.

Leadership sketchbook

You needn’t be an artist to find value in a “draw a leader” exercise. See how the strategy+business staff interpreted its own sketches to explore ideas about leadership.

Eager to test this “draw a leader” exercise, I asked an academic colleague to try it. He quickly sketched two figures, one of which was about three times taller than the other. The taller figure pointed upward and the shorter one looked up at the leader. There was a lot to interpret in a few hastily drawn lines. My colleague uses the words guide and guidance frequently in his writing on leadership, and those sentiments were reflected in the drawing. The leader was clearly guiding a follower upward as the follower looked to receive direction. I also saw the stereotype of the larger-than-life leader with all of the “right stuff” to inspire and motivate others and achieve great things. Finally, the two figures had an apparent relationship, showing my colleague agrees with the academic research positing that leadership exists in the connection between leader and follower, not in the traits or characteristics of the leader alone.

Drawing a leader is an exercise in visual thinking. It’s useful because it stimulates your brain differently than writing or speaking about leadership do. According to Heather Willems, coauthor of Draw Your Big Idea, drawing “stimulates cross-cognitive brain function” in ways that lead to deeper understanding. You call on memory, analysis, symbolism, and creativity simultaneously. (Full disclosure: I have hired Willems to work as a graphic recorder of meetings.)

Harvard neuroscientist Srini Pillay, author of Tinker Dabble Doodle Try, explained the cognitive benefits of drawing to me this way: “Your brain is wired for many aspects of ‘self,’ and you will represent each differently: regulation (you draw a controlling figure), knowledge retrieval (you draw a figure digging), observation (you draw a person looking through a telescope), esteem (you draw a person propping someone up), understanding (you draw a professor), agency (you draw Christopher Columbus), and self–other connection (you draw conjoined twins). These are some of the varied self-functions living in your brain.”

In short, the process of drawing a leader allows you to tap into what you really think of leadership. What comes to mind, and is then reflected in your sketch, helps to surface this understanding so that you can examine underlying experiences and assumptions about yourself, or perhaps another person you thought of, as you drew the leader.

The process of drawing a leader allows you to tap into what you really think of leadership.

Your assumptions may be obvious to you, or they may reveal cognitive biases of which you are unaware — another plus. In research reported last year by the New York Times, most people who were asked to draw an effective leader drew a male. Even women drew men. The implications are significant if not surprising: “Getting noticed as a leader in the workplace is more difficult for women than for men,” the article noted. This doesn’t end with gender. In the images, white was the predominant skin color.

Visual thinking can do more than offer a way to uncover these biases. In a recent study, researchers found that drawing was the most effective way to embed to-be-learned information in memory, because it promotes “the integration of elaborative, pictorial, and motor [function] codes, facilitating creation of a context-rich representation.” This suggests that drawing more diverse figures as leaders may help shape our concept of leaders, in much the same way that varying pronouns in text may shape our thinking about gender.

Starting to draw ideas can be intimidating for those of us who’ve been told that we lack artistic skills. I went to Willems for a tutorial, and she told me, essentially, to get over it. “Our brains want to make sense out of images. We’re hardwired to do it. It’s not about communicating the beauty; it’s about communicating the idea. If you can write your name, you can draw,” she said.

She went on to make the case that learning to draw is really about dissecting what’s in front of you and imagining it as different shapes. For example, a bookcase may just be a three-by-four grid of squares. “This helps break complex issues down into simple parts,” she said. She advises using basic shapes — rectangles, circles, and triangles. Combined and modified, they can become arrows, thought bubbles, and more. And simple stick figures can work as people.

She also told me to celebrate the lack of polish in my drawings: “Presenting something in pristine visual form can make it feel like the idea is finished rather than open to input from other people. A rough drawing on a whiteboard is more open to collaboration.” She reminded me that the classic image of a breakthrough business idea is a rough sketch on a cocktail napkin.

Now, with all of this background in mind, take another look at your drawing. Examine it as objectively as you can. What does it tell you about how you view leadership? What questions does it raise? How would your subordinates or your boss depict you?

You can see the results of my “draw a leader” test above. Although my sketch was subject to priming and other biases I’d accumulated in thinking and reading about the topic, I found it helpful in thinking about leadership. My first thought was of “T-shaped people,” who have both deep expertise and the ability to collaborate across disciplines. But I ended up drawing the climbing stick figure you see here. One hand is reaching back to the person’s followers and the other is extending forward toward whomever he or she is following, or else perhaps the goal to be attained.

This drawing reveals my view of the leader as a connector and catalyst for others. You may have your own analysis. Just draw it to find out.