Leadership lessons from a guitar hero

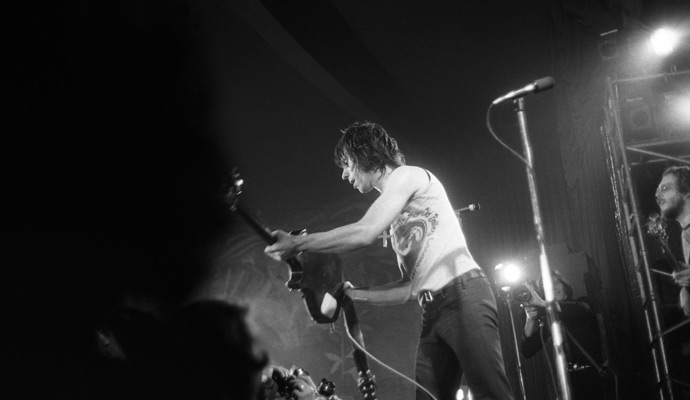

What the business world can learn about career success and longevity from rock virtuoso Jeff Beck.

About an hour into Still on the Run, a documentary exploring the career of rock guitar god Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton, another deity in the pantheon, pops up on screen and says, “I don’t even know how he’s doing it half the time.” Clapton is talking about Beck’s ability to give voice to the guitar. But his comment set me to wondering how Beck developed his unique style and what, if any, lessons his nearly 60-year career might offer those who aspire to reach the top of the business world.

With CEO tenure in large companies running five years or so, the fact that Beck has been numbered among the world’s best guitarists for about 10 times that long is worth exploring. Surely, innate talent and endless hours of practice count for a lot. But loads of guitarists have both, and haven’t had careers that lasted as long as the average CEO’s. Beck, however, has been an inveterate seeker of innovation in both technology and technique. And this habit has enabled the 74-year-old London-born musician to continuously expand his capabilities and transform his sound.

As biographer Martin Power tells it in Hot Wired Guitar: The Life of Jeff Beck (Omnibus Press, 2014), Beck’s parents valued musicianship, but not the electric guitar, which in the 1950s was associated with rockabilly and other disreputable musical genres. When his parents refused even to spring for new strings for a borrowed guitar, the teenager began building his own crude instruments. Unable to tune his early efforts, Beck learned to bend the strings to pitch while playing, a work-around that became a signature. The wannabe lead guitarist stole the pickup needed for his first electric guitar and built its amp in his school’s science department. Since then, Beck continually explored and adopted technological advances in guitar effects and electronics — such as tape-delay units, fuzz boxes, and guitar synthesizers — to shape and extend his playing.

Beck’s eagerness to learn and incorporate techniques from far-flung places is another hallmark of his career. Like Clapton, he learned from American blues giants — and rode the wave of cultural appropriation that gave rise to rock and roll. According to Power’s biography, Beck says that the first time he heard Jimi Hendrix play, he thought, “Oh, Christ, all right, I’ll become a postman.” Then he followed Hendrix around to learn how he created his sound. Other inspirations include a women’s choir that recorded Bulgarian folk songs, operatic tenor Luciano Pavarotti, and electronic dance music. Beck describes his resulting style as “a form of insanity…. A bit of everything, really. Rockabilly licks, Jimi Hendrix, Ravi Shankar, all the people I’ve loved to listen to over the years. Cliff [Gallup], Les [Paul], Eastern and Arabic music, it’s all in there.”

Beck’s quest for ever more potent combinations of technology and technique could be a prescription for burnout. But this guitarist also knows when to step away from the amp. When he reaches an impasse in his musical career, he takes a break until his creativity is recharged. Beck uses the time to build and rebuild hot rods, maintaining a fully equipped garage at his home. “It keeps the brain going…. You burn your fingers, there’s grinding and welding,” he says. “When the cars are shiny, I’m not playing. And when they are gathering dust, the guitars are out of their boxes.”

Another trait that supports Beck’s longevity is his lifelong refusal to pursue commercial success as a goal in and of itself. Some of Beck’s contemporaries — including Clapton and longtime friend Jimmy Page, who founded Led Zeppelin — became superstars, but he didn’t reach the same rarified level. Instead, he became more of a cult guitarist, who seemed determined to maintain his independence within the music industry and avoid the trappings of stardom.

Instead of driving for scale, Jeff Beck has chosen the path of the serial entrepreneur.

Indeed, whenever Beck approached superstardom, he usually backed away. After he replaced Clapton in the Yardbirds (and recruited Jimmy Page), the band veered away from the blues and began pursuing a more commercial sound. Beck left in the middle of a tour. “[I] couldn’t see any creativity going on in the Yardbirds,” he later said. After forming The Jeff Beck Group, which included Rod Stewart and Ronnie Wood, and becoming enormously popular in the U.S., Beck again quit during a tour and flew back to England — three weeks before the band was supposed to play the Woodstock festival. In 1985, he agreed to tour with the flamboyant Stewart — now a headliner — once again. This time, Beck quit just six nights into a 70-show tour, saying, “[It was] like vaudeville with him shaking his ass. I just couldn’t take it seriously.”

Instead of driving for scale, Beck has chosen the path of the serial entrepreneur. He forms bands based on the music that he wants to explore — funk, jazz fusion, etc. — and the people with whom he wants to work, tour, and record, and then moves on. This has led to fruitful collaborations with musicians like keyboardist Jan Hammer and lots of terrifically talented female vocalists, such as Beth Hart and Imelda May: “There [is] no macho, bare-chested testosterone element there,” says Beck, “just singing.” Beck also does frequent session work for other musicians. Stevie Wonder wrote “Superstition” for Beck after the guitarist played on one of his albums. (When Wonder’s management heard the soon-to-be hit, they insisted he keep it and record it himself.)

The ability of companies to maintain a sustainable competitive advantage has been declared unsustainable at regular intervals over the past quarter century — the work of professors Richard D’Aveni and Rita McGrath pops into mind as bookends for that line of thought. But Jeff Beck’s example suggests that sustainable competitive advantage is possible in a career in music and in business.