Poetry at work

The brilliant poet Wallace Stevens spent his career in the insurance industry. To what extent did these two aspects of his life nourish one another?

It’s hard to imagine anything less poetic than surety bonds, yet that was the odd corner of the insurance business that occupied Wallace Stevens, one of the 20th century’s greatest poets, for the bulk of his professional career.

Stevens went to law school after trying his hand at journalism and achieved financial security as a senior executive at what is now The Hartford. In 1935, his salary was US$20,000 — the equivalent of $372,000 in today’s money.

A steady professional income took the pressure off and, despite the demands of the job, made it possible for Stevens to create an astonishing body of imaginative work in his spare time. Check out his breathtaking “Sunday Morning,” to cite a single example.

Contrary to popular stereotypes, the list of poets who have spent their workdays in the bowels of capitalism is long. T.S. Eliot did some of his best work while employed at Lloyds Bank in London. Eliot, who died in 1965, worked from 9:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. and one Saturday out of four. It’s safe to say that he wasn’t plagued by emails from the boss during off hours, which he could therefore devote to writing “The Waste Land.”

Business jobs have provided sustenance for artists of all kinds. But poets in particular seem to have held executive positions that demand their own kind of creativity. Ted Kooser, a former poet laureate, was, like Stevens, an insurance executive. A.R. Ammons, whose laurels included the Pulitzer Prize, was for years a sales executive at his father-in-law’s scientific glass company. Richard Eberhart, another Pulitzer winner, worked at the Butcher Polish Company. James Dickey, the poet and novelist (Deliverance), was creative director at an advertising agency.

To what extent do these divided lives nourish one another? Did their business roles make these individuals better or worse poets? Perhaps more to the point, did writing poetry make them better or worse at business?

Clearly, working in business offers things otherwise missing from the life of a poet. There’s the paycheck, of course, and the health insurance. But there’s also the daily sense of accomplishment, the camaraderie of colleagues, and the useful disguise offered by a familiar role, one less likely to prompt bewilderment or derision in social settings than “poet.”

Despite these advantages, many poets who work in business quit when they can. Ammons took a position teaching at Cornell.

Yet some poets seem to quite like the idea of working in business. Dana Gioia got a Stanford MBA with the express purpose of making a living outside the academy. He spent 15 years as an executive, mostly at General Foods, while writing poetry, and has spoken of the excitement and rewards of his marketing career (though he ended up a professor nonetheless). Stevens, on the other hand, clung doggedly to his executive position, even turning down a professorship at Harvard.

In a remarkable essay called “Business and Poetry,” reprinted in his book Can Poetry Matter?, Gioia notes that poets almost never actually write about business, although they do sometimes write about money. Stevens, he reminds us, once wrote that, “Money is a kind of poetry,” and Gioia calls money the ultimate metaphor, “the one commodity that be translated into all else.”

Gioia, who was chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts from 2003 to 2009, has a great deal of management experience, and he argues that poets are good at that part of business. Writing poetry, in his view, is great preparation for the improvisational nature of senior leadership roles — which people sometimes reach as a result of their performance at tasks requiring far less imagination.

You might think that a business career would lead to poems written in plain language of the kind used in business. But Gioia finds the opposite to be the case. “The businessmen Stevens and Eliot pushed vocabulary and grammar not only to the limits of comprehensibility,” Gioia writes, “but quite often beyond.”

The poetry that Stevens wrote, like his surety work, was difficult. Surety bonds are guarantees that one party will fulfill its obligations to another; if it doesn’t, the bond issuer has to pay, but can seek to recover from the party whose actions it guaranteed. Whether the insurer is faced with a legitimate claim can be a matter of almost theological complexity, with large sums at stake. “Poetry and surety claims aren’t as unlikely a combination as they may seem,” Stevens once said. “There is nothing perfunctory about them, for each case is different.”

Stevens’s poetry, gemlike in its glitter and, at times, impenetrability, isn’t any easier to understand than his work at his day job. Yet it’s hard not to be moved by the gorgeous hedonism of it, to say nothing of its mysterious profundity. His great subject, you won’t be surprised to learn, wasn’t insurance but poetry itself.

It has to be living, to learn the speech of the place.

It has to face the men of the time and to meet

The women of the time. It has to think about war

And it has to find what will suffice. It has

To construct a new stage. It has to be on that stage

And, like an insatiable actor, slowly and

With meditation, speak words that in the ear,

In the delicatest ear of the mind, repeat,

Exactly, that which it wants to hear, at the sound

Of which, an invisible audience listens

Leading a dual life takes its toll. Stevens put off having children until he published his first book at the age of 44, and his devotion to his art, as well as to his employer, may have contributed to his unhappy domestic life. He and his wife lived in separate parts of their home, sharing a loveless marriage. “From the beginning, she and poetry were rivals for the poet’s attention,” writes James Longenbach in his book Wallace Stevens: The Plain Sense of Things.

Here’s how Stevens described his routine, which he evidently followed from 1916, when he moved to Hartford, to his death in 1955: “I rise at daybreak, shave, etc.; at six I start to exercise; at seven I massage and bathe; at eight I dabble with a therapeutic breakfast; from eighty-thirty to nine-thirty I walk down-town, work all day [and] go to bed at nine.”

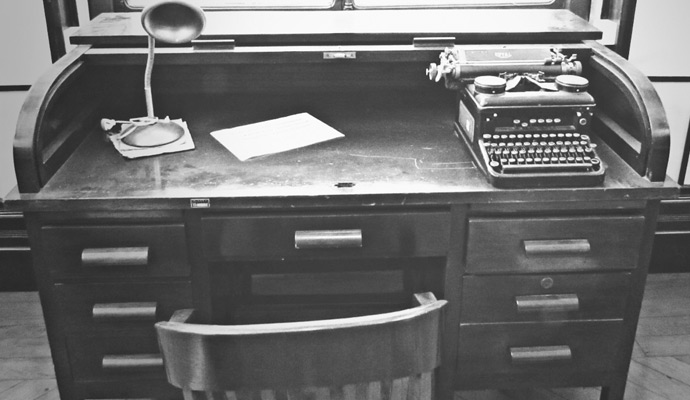

Evidently he composed quite a bit of poetry on the way to work. Having never learned to drive, Stevens walked to and from his office at the Hartford Accident and Indemnity Company, a distance of more than two miles each way. When he arrived, he would dictate to his secretary whatever verses were rolling around in his head. Evidently he paid her extra for doing his poetic work.

Stevens walked to his office at the Hartford Accident and Indemnity Company. When he got to work, he would dictate to his secretary whatever verses were rolling around in his head.

It can’t have been easy performing at such a high level at both business and poetry, and Gioia’s experience suggests what it might have cost him. Recalling his time at General Foods, Gioia told me: “I managed by giving up many things I would otherwise have enjoyed. No weekend trips, no television, no concerts, etc. Just work, family, writing. I simplified my life.”

Gioia agreed that it’s easier to write poems this way than whole books (“Poems are short”). He also acknowledges that doing what he and Stevens did is probably harder now, when “the Internet keeps business people tied to their jobs 24 hours a day,” and “there is less privacy and personal time.” Kenneth Koch addressed the sacrifices of a career in a little poem that begins:

You want a social life, with friends,

A passionate love life and as well

To work hard every day. What’s true

Is of these three you may have two

Exercise? Gioia solved this by following in Stevens’s footsteps: “I often composed poems while I walked for miles.”

In 1932, when Stevens was still struggling financially — and not writing poems — he began keeping a commonplace book, which is a sort of diary for entering noteworthy items from his reading. The very first entry is in French, and translates to: “Successful careers are those that realize in the man the dreams of the child.”

Surety bonds seem to have done the trick.