The wisdom of The Old Wives’ Tale

A 1908 novel about the fate of two sisters in Victorian England has a great deal to teach us about the challenges women face in the business world.

For a writer, Arnold Bennett was a pretty good businessman. The British novelist (1867-1931) earned enough from his prodigious output to buy not just one yacht but two — and the second was so vast, it required a crew of eight. “She’s not a yacht,” he exulted. “She’s a ship.”

Unjustly forgotten today, Bennett was a literary dreadnought during the first third of the last century. And unlike his squeamish fellow intellectuals in Britain, who shared the upper class’s disdain for “trade,” he was fascinated by business, which figured strongly in his work. His most popular book, The Old Wives’ Tale, published in 1908, overflows with insights great and small on business, the role of commerce in social change, and the struggles of women to make their way in a commercial world. Oh, and by the way, it also happens to be one of the greatest novels in the English language.

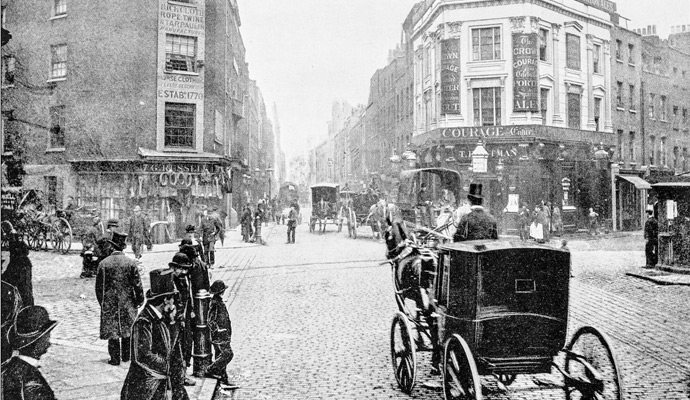

Bennett tells the story of Constance and Sophia Baines, loving sisters raised in the apartment adjoining their family’s respected clothing and fabric shop in the fictional Bursley, a grimy English pottery-making town. The book, like the lives of the sisters themselves, spans most of Queen Victoria’s long reign, which lasted from 1837 to 1901, and it can be read as a requiem for the Victorian values that shaped the girls. Those values — reticence, hard work, thrift, and obsessive self-restraint — are easy to mock but perhaps less easily dispensed with. And the Baines enterprise is suffused with them. Mr. Baines, their father, is so opposed to “puffing,” or self-promotion, that he can’t even bear to have a sign outside.

Through the story, Bennett builds a ferocious critique of Victorian constraints on women, who, in The Old Wives’ Tale, demonstrate great competence, insight, and fortitude. They are also very good at business. In fact, from the outset, women are the ones in charge. When the book opens, Mr. Baines has long since suffered a debilitating stroke that left him little more than a burdensome symbol of a dying patriarchy. Mrs. Baines ably runs the firm with the help of a mostly female staff and the young, indispensable Samuel Povey, whom Constance will eventually marry.

Constance, the older of the two, is content to learn the business and stay at home. But headstrong Sophia is determined to become a schoolteacher. The event that will upend the applecart is the snake-like arrival of Gerald Scales, who is not just a new salesman for one of the Baines’ suppliers but an avatar of modern commerce and the larger world’s increasingly insistent intrusions. It’s fitting that he’s the one Sophia finds irresistible.

Mrs. Baines does what she can, but Sophia will not be denied — and runs away with Gerald. Of course, he’s just as bad — in fact, he’s far worse — than her mother feared. When he abandons her in Paris, Sophia, apparently penniless, is forced to put her intelligence, discipline, and entrepreneurial skills to use. Unattached women had few good options in 19th-century France, and Sophia is determined not to debase herself.

Sophia had the foresight to appropriate a chunk of the money her husband has been busy squandering, and sewed it into her hem for safekeeping. When the reptilian Gerald flees, she makes good on his debt to a trusted friend and uses the rest of her stash to get a start renting out rooms in a Paris flat — in other words, to go into business for herself. The outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War triggers inflation in food prices, but Sophia, foreseeing further scarcity, stocks up nonetheless. When Paris falls under siege, she makes a killing while keeping herself and her tenants fed — fending off suitors and sexual harassers alike. Soon, by means of a ruthlessly lowball offer, she buys Frensham’s, a small hotel catering to English tourists in a better part of town. Success follows success.

“She’s made a lot of money here,” one savvy guest confides to another, adding: “There’s no reason why a place like this shouldn’t be five times as big as it is. Ten times. The scope’s unlimited…. But then, as she says, she doesn’t want the place any bigger. She says it’s now just as big as she can handle. That isn’t so. She’s a woman who could handle anything — a born manager.”

“She says it’s now just as big as she can handle. That isn’t so. She’s a woman who could handle anything — a born manager.”

Sophia has gained wisdom, wealth and independence, but her life is blighted by loneliness and exile. This is partly due to her culture’s powerful taboos against women’s freedoms, which left her no space between celibacy and elopement. Yet she is also her own jailer, simply because she is too proud to go home. The aptly named Constance, meanwhile, stays put in Bursley, and through her we witness the evolution of her family’s business — and in microcosm, the changes that have come to all businesses over the years. In the store, items are tagged with superlatives that might have embarrassed old Mr. Baines. A big sign is mounted outside. There is even an annual sale.

After Samuel dies, Constance sells the shop. Her timing is impeccable, as, sure enough, the store’s once-prized location is becoming a liability thanks to technology: the new trams and railways that make a larger neighboring town much easier for shoppers to reach. Eventually the Baines enterprise is superseded by a large chain of clothiers, which erects a much larger sign, plasters the building with posters, and sells cheap goods at rock-bottom prices. Their overcoats, unlike the Baines overcoats, aren’t made to last — just to move.

The Old Wives’ Tale isn’t just about business, of course, and Bennett doesn’t particularly approve — or lament — the passing of Victorian traditions. The book is far more concerned with the lives of its sisterly protagonists, whose unchanging natures conspire with chance to determine their fates. But it is also a book about risk, the ways tradition can mitigate it, and the readiness of youth to embrace it. Bennett is particularly sensitive to the risks facing women, risks that made marriage or even flirtation a momentous step with potentially lifelong ramifications.

The author’s profound understanding of human nature is matched by his insight into the impact of business on society. He saw that commerce could be not just liberating, but destabilizing. Decades before Joseph Schumpeter coined the term, Bennett foresaw that creative destruction doesn’t look terribly creative to its victims. He also knew that prosperity can undermine the values that produced it — as in the case of Constance and Samuel’s son, an only child indulged by his affluent, older parents into idleness and uncaring adulthood. Finally, Bennett recognized that character and values can bring different people around to the same place despite divergent fortunes. Sophia and Constance both were circumscribed by commerce and its demands, and so, despite their different choices, their lives end up not so very different at all.