The New Golden Age

The history of investment and technology suggests that economic recovery is closer than you think, with a new silicon-based global elite at the helm.

(originally published by Booz & Company)Recession. Depression. War. Terrorism. Unemployment. Enemies on the march. Every day the headlines remind us that there is plenty to worry about and more than enough real suffering to try our souls.

And yet, if we step back and take a longer view, we see that industrial society has been here before. The global economy is poised to enter a new phase of robust, dependable growth. Technological and economic historian Carlota Perez calls it a “golden age.” Such ages occur roughly every 60 years, and they last for a decade or more, part of a long cycle of technological change and financial activity. (See Exhibit 1.)

This doesn’t mean that the world’s political and economic problems will go away. But whereas the details of long cycles vary, the overall pattern of progress remains the same: An economy spends 30 years in what Perez calls “installation,” using financial capital (largely from investors) to put in place new technologies. Ultimately, overinvestment and excessive speculation lead to a financial crisis, after which installation gives way to “deployment”: a time of gradually increasing prosperity and income from improved goods and services.

This time, linchpins of the golden age will include the worldwide build-out of a new services-oriented infrastructure based on digital technology and a general shift to cleaner energy and environmentally safer technologies. In the emerging markets of China, India, Brazil, Russia, and dozens of smaller developing nations, a billion people will enter the expanding global middle class.

The idea of sustained prosperity may seem implausible in early 2010. But no one would have believed, during the dark days at the end of World War II, that the global economy was heading for two decades of broad-based economic growth and relative peace, led by a new establishment of business and political leaders.

Tracking the Cycle

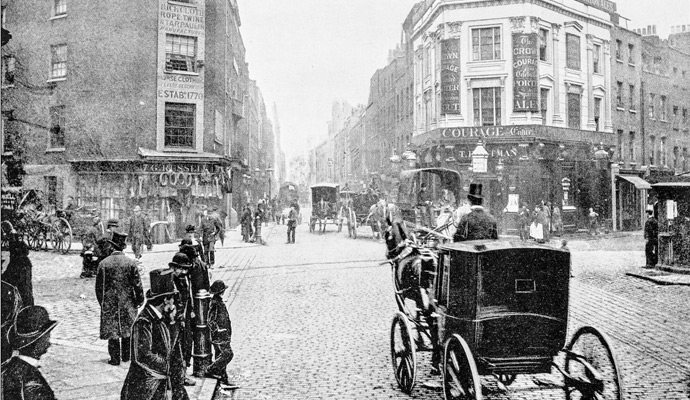

Long cycles of technology and investment have been tracked and analyzed by an impressive roster of scholars, including Perez, Joseph Schumpeter, and others. (See “Carlota Perez: The Thought Leader Interview,” by Art Kleiner, s+b, Winter 2005.) Five such cycles have occurred since the late 1700s. The first, lasting from the 1770s through the 1820s, was based on water power and introduced factories and canals, primarily in Britain. The second, the age of steam, coal, iron, and railways, lasted from the 1820s to the 1870s. The third, involving steel and heavy engineering (the giant electrical and transportation technologies of the Gilded Age), expanded to include Germany and the United States. This cycle ended around 1910, giving way to the mass production era of the 20th century, a fourth long cycle encompassing the rise of the automobile, petroleum-based materials, the assembly line, and the motion picture and television.

Our current long cycle, which began around 1970, is based on silicon: the integrated circuit, the digital computer, global telecommunications and the Internet. It may feel like this technology has run its course, but the cycle is really only half over. In a typical “technological–economic paradigm,” as Perez calls it, new technologies are rolled out during the first 30 years of installation with funding from financial capital. Investors are drawn in because they receive speculative gains that come, in effect, from other people making similar investments. Gradually this leads to “frenzy”: Investors can’t be certain which inventions will succeed and which new enterprises will endure, so they bet wildly. As some bets lead to rapid gains, enthusiasm and impatience fuel a more widespread appetite for jumping on board, risks be damned. The consequence is irrational exuberance, a crash — and then a period of crisis.

The current crisis began in 2000 with the Internet bubble collapse. It was prolonged by the financial-services industry. Not wanting to give up easy profits, and applying the technological innovations that computer “geeks” had provided, traders continued to push for rapid returns. Ever more elaborate derivative instruments were concocted; increasingly complicated computer models replaced experienced judgment; and highly leveraged bets piled into such “sure thing” arenas as real estate. This culminated in the catastrophic meltdown of 2008 and a historic moment of shifting establishment priorities.

Every crisis ends in such a moment. The last crisis, which began with the stock market crash of 1929, ended with the Bretton Woods agreements of 1944. In each case, once the widespread debacle bottoms out, the speculators of the old era are reined in, expectations are reset, and new business and government elites start to rebuild the world’s governing institutions. After World War II, the locus of power and influence was the oil economy. Rockefeller family interests influenced the governance of companies, governments, and supranational institutions (such as the International Monetary Fund, the Council on Foreign Relations, and the Trilateral Commission) for many years. The United Nations headquarters in New York is built on former Rockefeller real estate; the World Bank’s first president, John J. McCloy, had been a Rockefeller-connected lawyer and a family friend. The symbols of elite power, including the Rockefeller-built World Trade Center, were all linked to oil.

Only with a similar restructuring can a new period of extended growth, a golden age, be ushered in. This time, the leaders will be linked to silicon. IBM, Intel, and Microsoft will be more important in the next two decades than Exxon or the World Bank. IBM’s deep engagement with national and regional economic planners, particularly in emerging economies like China and India, will probably become the prevailing model for corporate growth.

When deployment begins, general assumptions about business shift accordingly. Financial capital, which is relatively indifferent to particular technologies, becomes less of an economic force. Businesses depend more on industrial capital, derived from profits from the sale of goods and services. Executives with a greater interest in long-term stability than in rapid returns are placed in charge of global affairs.

There are clear signs that this is happening now. Financial regulations are being put in place around the world to improve market monitoring, limit leverage, and mandate heftier reserves. Wall Street’s leaders (and their equivalents in the City of London and bourses elsewhere) are undergoing a fundamental reassessment. Far too much has been lost by far too many individuals, in both money and reputation, to allow a widespread return to the old fast-and-loose investment casino. It is no longer practical for financial institutions to operate by rewriting risk “insurance” over and over again, in an opaque market without established rules. To be sure, new schemes are always being hatched, but the people who run Wall Street (traditionally scions of wealth) have lost confidence in these interloping “smart guys.”

One telling indicator of this shift from speculation to real growth is the official attitude toward bubbles. In the 1990s, the U.S. Federal Reserve, under Alan Greenspan, took a hands-off approach to speculation. Now the Fed is discussing what actions it might take to cool off overheated markets in advance, and is admitting that its earlier approach to bubbles and risk management was a mistake. New authority is being sought by regulators such as the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission and its European counterparts. And, although some on Wall Street will surely object, the most powerful of the houses, Goldman Sachs, has ex-employees in key Washington positions who are pushing for the new rules. Many believe it is in the interest of Goldman and others to rein in “rogue” trading activities, since this would not only make returns more reliable, but raise barriers to entry in the industry.

The Emerging Silicon Economy

Goldman Sachs will probably be part of the new Silicon Establishment, along with dominant enterprises in information and communications technology and others involved in deploying these technologies. For the first time in decades, a commonality of purpose and shared reservoir of knowledge will bridge the many differences among governing bodies. Many people have lived their adult lives without responsible and capable leadership; to their surprise, the next 30 years will be a time when authority — both in government and in business — can be trusted. Companies such as Microsoft, IBM, and Intel have matured during the past 20 years, weathering conflicts — IBM’s near breakup, Microsoft’s antitrust battles, Intel’s confrontations with other chip manufacturers — that threatened their corporate existence and forced them to reconsider their core strategies and redefine their long-term goals. Meanwhile, major government agencies, such as the U.S. Army, the U.K. National Health Service, and various ministries in emerging market governments, have become the most significant and sophisticated buyers of large-scale information technology in the world today. Both customers and manufacturers have learned to factor life-cycle costs and long-term plans into their decisions.

The priorities of the new technology-based elite include access to larger groups of customers, such as those in emerging nations. Thus, one hallmark of the coming golden age will be its global inclusiveness. Although oppression and slavery may remain widespread, the social systems that reinforced a “haves” and “have-nots” status quo, holding back economic opportunities for the majority of the human population, will give way. A billion new people will gain a productive foothold that would have been hard to imagine just a few years ago.

A new global economic infrastructure is emerging, built on networked, shared computing resources and commonly called cloud computing. Google alone has more than 10 million servers, and other companies are building comparable cloud infrastructures. As enterprises exit the recent slump, widespread investments will be made in private clouds, shifting business from high-fixed-cost data centers, and reshaping many public and consumer services. A more responsible approach to the natural environment is also gaining ground, one that advocates using energy more efficiently and reducing pollution, greenhouse gases, and hazardous waste. Meanwhile, innovative new service offerings will displace entrenched but inefficient medical and financial practices.

Although the benefits will be widely distributed, not everyone will be happy. For those who would like to continue rolling the dice of global finance, a more planned and regulated future will feel like an attack on freedom. Adding a billion new people to the global middle class will add to the labor arbitrage that has already begun to affect many lawyers, journalists, software engineers, and accountants. It will now affect professionals in health, finance, and education. As cloud-based financial services spread, will we really need as many stockbrokers? As credible expertise becomes more easily available, will we still need so many intermediaries?

After a couple of decades, the silicon era will grow moribund, as the oil era did before it. Sometime around 2030, there will be a silicon equivalent to the oil crisis of the early 1970s. Then a new long cycle will emerge. This one will probably be based on the technologies just emerging now: biotechnology and nanotechnology, along with molecular manufacturing (the ability to cheaply build any material from scratch). Then the pattern of frenzied investment will begin again, with another cycle to come.![]()

Author profile:

- Mark Stahlman is a Wall Street technology strategist who has been writing about tech-driven growth cycles for more than 20 years.